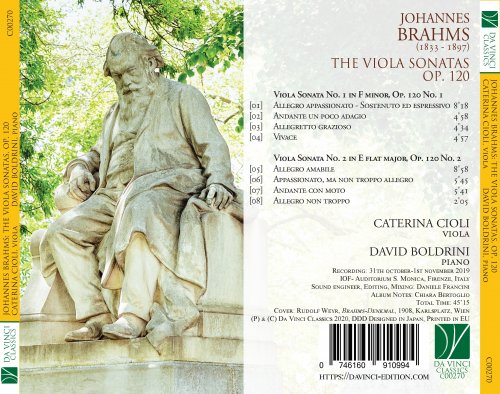

Caterina Cioli - Johannes Brahms: The Viola Sonatas, Op. 120 (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Caterina Cioli

- Title: Johannes Brahms: The Viola Sonatas, Op. 120

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 45:12 min

- Total Size: 223 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Viola Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120 No. 1: I. Allegro appassionato

02. Viola Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120 No. 1: II. Andante un poco adagio

03. Viola Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120 No. 1: III. Allegretto grazioso

04. Viola Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120 No. 1: IV. Vivace

05. Viola Sonata No. 2 in E-Flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2: I. Allegro amabile

06. Viola Sonata No. 2 in E-Flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2: II. Allegro appassionato

07. Viola Sonata No. 2 in E-Flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2: III. Andante con moto

08. Viola Sonata No. 2 in E-Flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2: IV. Allegro

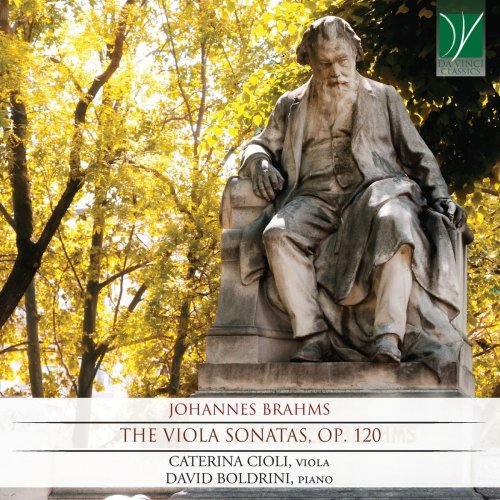

The outward appearance of Johannes Brahms is well documented, throughout his entire life, by a series of painted, drawn and photographed portraits, which reveal (not unlike the self-portraits constantly painted by Rembrandt) how life writes itself on the face of human beings. As a young man, Brahms was extremely handsome; his portraits exude a sense of self-confidence, of youthful and almost heroic energy, together with an unmistakably honest and transparent expression. The music he wrote in those same years is quintessentially Romantic, meaning that it represents the contrasts, outbursts, passions and extreme feelings of the Romantic era.

As the years went by, the portraits by Brahms increasingly became those of a wise man, whose imposing beard lends him an almost prophetic or priestly air, but who evidently maintains in his eyes – though increasingly hidden by massive eyebrows – a fiery and impassionate nature. And the music he wrote in his later years is also quintessentially Romantic, but in an utterly different fashion as that of his earlier years: here, Romantic indicates the consuming, unquenchable, persistent and infinite nostalgia which permeates the music, the poetry and the visual arts of Romanticism.

And while the youthful passions of the youthful Romanticism were expressed in music by many other great musicians (such as Chopin or Schumann) who succeeded in depicting the sound of heroism, passion and ecstasy, Brahms is probably a standalone as far as the infinite nostalgia of old age is concerned. This may be due to the fact that he lived longer than the other great Romantic composers (though, paradoxically enough, the only other musician who was able to describe nostalgia as effectively as Brahms was Schubert, who was barely thirty-one when he died); or to the fact that he was born somewhat later than the others, and thus saw the sunset of the nineteenth century and the dusk surrounding the hopes of the earlier generation; or simply to his character, which was shaped by life just as happened to his physical appearance.

Be it as it may, the late works by Brahms are one of the best musical expressions ever written for the feelings of loss, regret, loneliness and for the pain of ageing; for that typically German word, Sehnsucht, whose meaning intertwines desire with longing, an aspiration for the infinite with the grief arising from the realization of the irretrievability of the past.

Brahms’ late works are not always veiled in darkness, of course; however, their light is never the full, shining light of a summer midday, but rather the caressing light of an autumn sundown. Both the colours of autumn and those of sunset may be friendlier and warmer than the brighter shades of their younger and more energetic counterparts; yet, they are tinged with a bittersweet nuance, which never leaves room for the carefree dreams of the young. There are lullabies, in Brahms’ late output; but their infinite tenderness acquires a heartbreaking dimension when one realizes that they are the lullabies for the children Brahms never had. There is hope, too; but it is the kind of hope which can be expressed only by those who have experienced the full gamut of grief.

All of these feelings are perfectly embodied by the two masterpieces recorded in this Da Vinci Classics production, i.e. the two Sonatas op. 120.

Brahms’ routine, in his mature years, was to spend the summer months in some idyllic place in the mountains, where he would compose, surrounded by nature; during the winter months, he could not find the same kind of concentrated attention, and so he rather performed, conducted or edited his compositions. However, by the early 1890s, Brahms had decided that his compositional activity had come to an end: in 1891, he had written to his publisher Simrock, sending him a copy of his last will and testament, and explaining that the last of his Volkslieder (“Verstohlen geht der Mond auf”), which portrayed the image of a dog chasing its tail, represented the closure of a circle, the completion of an orbit, the end of his creative stage.

This circular image seems to allude to Nietzsche’s eternal return, and to the despairing feeling of imprisonment and of an inescapable fate it embodies. However, in spite of what Brahms himself had decided, the last word had not yet been written, and the circle was not as close as it appeared.

The unforeseen showed itself in the person of Richard von Mühlfeld, solo clarinettist in the Orchestra of Meiningen; a virtuoso of the instrument, who was gifted with an extraordinary tone, deep, expressive, intense and warm. It was the sound of autumn, the reddish sound of the leaves whose most beautiful colours appear as they are ready to fly from their trees. It was the right sound for Brahms’ mood. The clarinet was a relatively young instrument, and its repertoire did possess already some unsurpassable gems (such as the masterpieces by Mozart), though many timbral and technical possibilities remained still unexplored. Mühlfeld was willing to investigate them, and the union of the “right sound”, of compositional challenges, and of a first-rate performer ignited Brahms’ imagination. Thus, he started to compose a series of unforgettable pieces for the clarinet, such as the Trio op. 114 and the B-minor Quintet op. 115. After them, there came the last collections of piano pieces, one greater than the other; and, finally, almost as an afterthought, the two Sonatas op. 120 and the Chorale Preludes for the organ. (As an aside, it may be said that the fact that Brahms’ “very last” word was represented by religious pieces is a further ray of hope breaking the anguishing Nietzschean circle he had imagined a few years earlier).

These two Sonatas were conceived by the composer with Mühlfeld’s tone in mind; yet, from the very outset, Brahms created a twin version for the viola (and a lesser-known one for the violin, which departs more radically from the other two versions). Brahms wrote them in 1894, once more when on holiday at Bad Ischl; he asked Mühlfeld to join him in order to rehearse them, but it was only in September that they were able to see each other in Vienna, and to play the freshly-composed pieces. Later on, they performed them privately for Duke Georg (Mühlfeld’s employer), and for Clara Schumann, for whom Brahms had always nourished love, affection and an intense and deep respect. Evidently (and understandably) the pieces pleased both the clarinetist and the first listeners, so that a public premiere was scheduled for the beginning of 1895; paying homage to Mühlfeld’s gifts (which had prompted the creation of such beautiful music, and had almost forcibly extracted Brahms from his creative exile), the composer surrendered his rights to the performer, thus sealing in a very explicit fashion the relationship of friendship and mutual esteem which had fostered the composition of these pieces.

The two Sonatas are markedly different from each other, though both are relatively concise, and neither features those climaxes of excitement which appear so frequently in the Cello Sonatas or in the D-minor Violin Sonata.

Here, we find that “amiability” which appears also in the tempo indication of the first movement of op. 120 no. 2; a good-natured gaze which embraces the past and is capable of transforming even the deepest regret into benevolent and merciful compassion. The F-minor Sonata is darker in tone, with moments of serious intensity, tension and tenderness, but also with a pre-Mahlerian transformation of dance-rhythms into a symbol for the caducity of life. By way of contrast, the E-flat major Sonata is full of remembrance; the concluding variations are a masterful exploration of the possibilities of nuancing a theme through slight changes in tempo, harmony, rhythm and melody. Brahms (following in Beethoven’s footsteps) had studied the form of variations for his entire life, and these enchanting examples from his latest years embody an unsurpassed compositional wisdom, knowledge and ability.

They also symbolize the itinerary of life, which is (just like a Theme and Variations) a fascinating intertwining of repetition and changes; the “theme” which Time plays for us every day is constantly changed by the great and small things of life, which adorn the days and transform them continuously.

Thus, with these two masterpieces, Brahms gave us a touching and enchanting perspective on how art, beauty and friendship may turn even the loneliness of ageing into a new spring, in which there is still room for blossoms of perfect artistry as the two Sonatas op. 120.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

As the years went by, the portraits by Brahms increasingly became those of a wise man, whose imposing beard lends him an almost prophetic or priestly air, but who evidently maintains in his eyes – though increasingly hidden by massive eyebrows – a fiery and impassionate nature. And the music he wrote in his later years is also quintessentially Romantic, but in an utterly different fashion as that of his earlier years: here, Romantic indicates the consuming, unquenchable, persistent and infinite nostalgia which permeates the music, the poetry and the visual arts of Romanticism.

And while the youthful passions of the youthful Romanticism were expressed in music by many other great musicians (such as Chopin or Schumann) who succeeded in depicting the sound of heroism, passion and ecstasy, Brahms is probably a standalone as far as the infinite nostalgia of old age is concerned. This may be due to the fact that he lived longer than the other great Romantic composers (though, paradoxically enough, the only other musician who was able to describe nostalgia as effectively as Brahms was Schubert, who was barely thirty-one when he died); or to the fact that he was born somewhat later than the others, and thus saw the sunset of the nineteenth century and the dusk surrounding the hopes of the earlier generation; or simply to his character, which was shaped by life just as happened to his physical appearance.

Be it as it may, the late works by Brahms are one of the best musical expressions ever written for the feelings of loss, regret, loneliness and for the pain of ageing; for that typically German word, Sehnsucht, whose meaning intertwines desire with longing, an aspiration for the infinite with the grief arising from the realization of the irretrievability of the past.

Brahms’ late works are not always veiled in darkness, of course; however, their light is never the full, shining light of a summer midday, but rather the caressing light of an autumn sundown. Both the colours of autumn and those of sunset may be friendlier and warmer than the brighter shades of their younger and more energetic counterparts; yet, they are tinged with a bittersweet nuance, which never leaves room for the carefree dreams of the young. There are lullabies, in Brahms’ late output; but their infinite tenderness acquires a heartbreaking dimension when one realizes that they are the lullabies for the children Brahms never had. There is hope, too; but it is the kind of hope which can be expressed only by those who have experienced the full gamut of grief.

All of these feelings are perfectly embodied by the two masterpieces recorded in this Da Vinci Classics production, i.e. the two Sonatas op. 120.

Brahms’ routine, in his mature years, was to spend the summer months in some idyllic place in the mountains, where he would compose, surrounded by nature; during the winter months, he could not find the same kind of concentrated attention, and so he rather performed, conducted or edited his compositions. However, by the early 1890s, Brahms had decided that his compositional activity had come to an end: in 1891, he had written to his publisher Simrock, sending him a copy of his last will and testament, and explaining that the last of his Volkslieder (“Verstohlen geht der Mond auf”), which portrayed the image of a dog chasing its tail, represented the closure of a circle, the completion of an orbit, the end of his creative stage.

This circular image seems to allude to Nietzsche’s eternal return, and to the despairing feeling of imprisonment and of an inescapable fate it embodies. However, in spite of what Brahms himself had decided, the last word had not yet been written, and the circle was not as close as it appeared.

The unforeseen showed itself in the person of Richard von Mühlfeld, solo clarinettist in the Orchestra of Meiningen; a virtuoso of the instrument, who was gifted with an extraordinary tone, deep, expressive, intense and warm. It was the sound of autumn, the reddish sound of the leaves whose most beautiful colours appear as they are ready to fly from their trees. It was the right sound for Brahms’ mood. The clarinet was a relatively young instrument, and its repertoire did possess already some unsurpassable gems (such as the masterpieces by Mozart), though many timbral and technical possibilities remained still unexplored. Mühlfeld was willing to investigate them, and the union of the “right sound”, of compositional challenges, and of a first-rate performer ignited Brahms’ imagination. Thus, he started to compose a series of unforgettable pieces for the clarinet, such as the Trio op. 114 and the B-minor Quintet op. 115. After them, there came the last collections of piano pieces, one greater than the other; and, finally, almost as an afterthought, the two Sonatas op. 120 and the Chorale Preludes for the organ. (As an aside, it may be said that the fact that Brahms’ “very last” word was represented by religious pieces is a further ray of hope breaking the anguishing Nietzschean circle he had imagined a few years earlier).

These two Sonatas were conceived by the composer with Mühlfeld’s tone in mind; yet, from the very outset, Brahms created a twin version for the viola (and a lesser-known one for the violin, which departs more radically from the other two versions). Brahms wrote them in 1894, once more when on holiday at Bad Ischl; he asked Mühlfeld to join him in order to rehearse them, but it was only in September that they were able to see each other in Vienna, and to play the freshly-composed pieces. Later on, they performed them privately for Duke Georg (Mühlfeld’s employer), and for Clara Schumann, for whom Brahms had always nourished love, affection and an intense and deep respect. Evidently (and understandably) the pieces pleased both the clarinetist and the first listeners, so that a public premiere was scheduled for the beginning of 1895; paying homage to Mühlfeld’s gifts (which had prompted the creation of such beautiful music, and had almost forcibly extracted Brahms from his creative exile), the composer surrendered his rights to the performer, thus sealing in a very explicit fashion the relationship of friendship and mutual esteem which had fostered the composition of these pieces.

The two Sonatas are markedly different from each other, though both are relatively concise, and neither features those climaxes of excitement which appear so frequently in the Cello Sonatas or in the D-minor Violin Sonata.

Here, we find that “amiability” which appears also in the tempo indication of the first movement of op. 120 no. 2; a good-natured gaze which embraces the past and is capable of transforming even the deepest regret into benevolent and merciful compassion. The F-minor Sonata is darker in tone, with moments of serious intensity, tension and tenderness, but also with a pre-Mahlerian transformation of dance-rhythms into a symbol for the caducity of life. By way of contrast, the E-flat major Sonata is full of remembrance; the concluding variations are a masterful exploration of the possibilities of nuancing a theme through slight changes in tempo, harmony, rhythm and melody. Brahms (following in Beethoven’s footsteps) had studied the form of variations for his entire life, and these enchanting examples from his latest years embody an unsurpassed compositional wisdom, knowledge and ability.

They also symbolize the itinerary of life, which is (just like a Theme and Variations) a fascinating intertwining of repetition and changes; the “theme” which Time plays for us every day is constantly changed by the great and small things of life, which adorn the days and transform them continuously.

Thus, with these two masterpieces, Brahms gave us a touching and enchanting perspective on how art, beauty and friendship may turn even the loneliness of ageing into a new spring, in which there is still room for blossoms of perfect artistry as the two Sonatas op. 120.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads