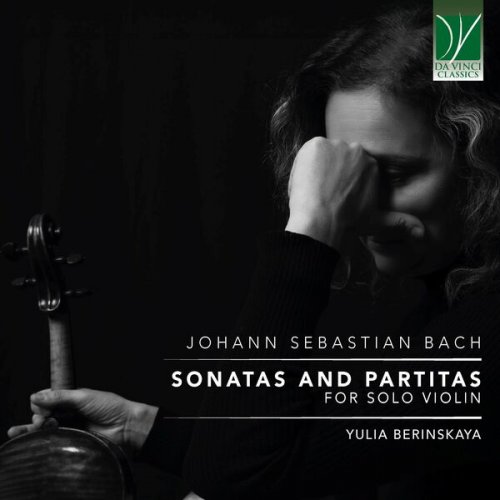

Da Vinci Classics - Johann Sebastian Bach: Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Da Vinci Classics

- Title: Johann Sebastian Bach: Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:58:37

- Total Size: 600 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

CD1

01. Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001: I. Adagio

02. Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001: II. Fuga

03. Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001: III. Siciliana

04. Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001: IV. Presto

05. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 1, Allemanda

06. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 2, Double

07. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 3, Corrente

08. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 4, Double

09. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 5, Sarabande

10. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 6, Double

11. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 7, Tempo di Bourrée

12. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 8, Double

13. Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Minor, BWV 1003: I. Grave

14. Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Minor, BWV 1003: II. Fuga

15. Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Minor, BWV 1003: III. Andante

16. Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Minor, BWV 1003: IV. Allegro

CD2

01. Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: I. Allemanda

02. Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: II. Corrente

03. Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: III. Sarabanda

04. Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: IV. Giga

05. Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: V. Ciaccona

06. Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1005: I. Adagio

07. Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1005: II. Fuga

08. Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1005: III. Largo

09. Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1005: IV. Allegro assai

10. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 1, Preludio

11. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 2, Loure

12. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 3, Gavotte en rondeau

13. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 4, Menuet I - Menuet II

14. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 5, Bourrée

15. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 6, Gigue

Under many aspects, Bach was one of the greatest innovators in the history of music. Few things he created from scratch; but none of the elements he received from tradition he left untouched or adopted supinely. And one of the most impressive innovations that should be ascribed to his genius is the creation of a repertoire of unaccompanied works for the solo violin and cello, which demonstrates the possibility for these two instruments to sustain and support a whole musical discourse without the need of an accompaniment.

This is one of the cases where the “invention” of a form cannot be credited to Bach. Works for unaccompanied violin were not unheard-of at his time, although they constituted a niche repertoire. What Bach did was to elevate this possibility to previously unattained summits of artistry, as is abundantly demonstrated by the six masterpieces recorded here.

By its nature, the violin is an instrument which seems to require an accompaniment. Due to its physical conformation, and since geometry teaches us that no straight-line touches three non-aligned points, no more than two notes at a time can be logically played on it. If, in fact, the bow is a straight line, and the strings are seen (in their section) as non-aligned points, if follows that the maximum polyphony allowed on a violin is a diphony, the compresence of two notes. As a matter of fact, the situation is more complex than this. On the one hand, the bow is not a straight line: that is, it possesses some elasticity and flexibility, and therefore, depending on the pressure imparted by the performer, it is possible also to make three strings resound at the same time. Secondly, the possibility of arpeggiating chords (i.e. to play their notes in close sequence, so as to create the impression of simultaneity without actually producing it) is another resource available for composers. However, this kind of aural illusion works better with chords (i.e. harmonies) than with polyphony proper (i.e. counterpoint), because in order to perceive two melodic lines as such, as a true polyphony, they should be not just played, but also sustained at the same time. Bach brilliantly solves this problem by creating either subjects or countersubjects which have an important component of silence (through rests or staccatos), so as to allow the listener to experience some degree of fluidity without actually demanding it to the performer.

Bach united in his person a palette of skills which were, each per se, extremely rare. He was a very skilled violinist himself, although his favourite instrument was the organ. Still, he was extremely proficient in violin performance, and therefore knew perfectly well what a violin and a violinist can do, even though it was previously unheard-of or at least very unusual. He had a unique contrapuntal imagination (as is witnessed by his sons and pupils), which allowed him to deduce and understand the possibilities of a given subject in terms of polyphonic intertwining. He had great experience in the composition of dances, for solo instruments such as the keyboard up to large and even to orchestral ensembles. In short, nobody could have composed the Violin Sonatas and Partitas at the same level as he did.

In spite of this, these masterpieces remained dead letter for more than a century. Not only were they considered as too difficult to play, too complex technically and with almost unsurmountable issues; but they were also thought to be unrewarding, unfit for public performance, puzzling for listeners, incomplete, unsatisfactory. The most striking aspect is that view was held not only by people whose musical knowledge was superficial, but also by some of the finest musicians of the nineteenth century. Even more impressive is that some of them were among the most enthusiastic of Bach enthusiasts; they were among the promoters of the publication of Bach’s complete works, and among those supporting and fostering the public performance of his works.

Indeed, it was precisely with the goal in mind of disseminating these works, i.e. to promote their knowledge and “acceptability”, that musicians of the standing of Mendelssohn and Schumann realized what today seems a rather arbitrary undertaking, i.e. the creation of piano accompaniments for Bach’s unaccompanied violin masterpieces.

These piano accompaniments make explicit what the original scores had left implicit, i.e. a full harmonic texture and a complete polyphonic writing. In this fashion, the musical discourse is certainly easier to follow by the hearer, who is not required to work with his or her imagination as intensely as Bach’s original score asks for. When, in fact, there are gaps in the musical line, the kind of listening that music requires is very active; the listener’s imagination must supply for the missing lines.

It should also be added that these Sonatas and Partitas are no less demanding from the interpretive viewpoint than from the merely technical. Their extreme beauty requires exceptional understanding and skill of the interpreter; their undeniable spirituality invites a contemplative gaze on transcendence expressed through music; their texture requires extreme nuancing in terms of timbre, volume, bowing etc.

It can be said, therefore, that if these Solos represent a summit of compositional virtuosity (in Bach’s ability to create aural illusions, structuring full contrapuntal and harmonic writing for the unaccompanied violin), of performative virtuosity (in the extreme demands they pose to the interpreter), of interpretive virtuosity (in the high requirements to the musician’s understanding and rendition), but also – in a manner of speaking – of “listening virtuosity”. The ideal listener of these works is a “virtuoso listener”, one who knows how to listen, what to listen, and is happy to be involved in an arduous, demanding, but also very rewarding itinerary with the composer and the performer.

All this leads us to wonder who the intended performer and/or dedicatee of these works at the time of their composition was. No information has come to us; hypotheses involve an exceptionally gifted violinist, as yet unknown; a monarch or aristocrat who had at his or her service one such violinist and who may ask the performer to play them for him or her; or, perhaps most likely, Bach himself.

The number six was one particularly liked by Bach (and by many of his contemporaries) for collecting the best fruits of his creativity: there are six Brandenburg Concertos, six English Suites, six French Suites, six keyboard Partitas, six Cello Suites, and the Forty-Eight Preludes and Fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier are eight times six. It may be argued, therefore, that Bach had imagined the possibility of publishing these works; however, if this had been in his mind, he did not pursue this course of action. Among these six works, three are Sonatas, which follow the slow/quick/slow/quick scheme of the church Sonata (including the contrapuntal, fugato movements which characterize this particular genre). The other three, commonly called Partitas, were actually titled “Partie” (plural of Partia, a term commonly used at Bach’s time). As frequently happens with Bach, the pieces follow a harmonious ordering in terms of keys and modes; Sonatas and Partitas alternate with each other.

The “Partie” are suites of dances, and although Bach generally remains faithful to the traditional suite scheme which he employs in his other sets of suites, there are some notable exceptions and innovations. For example, the B-minor Partita is structured in pairs of movements: examples of the traditional dances of the suite are always followed by a variation, called “Double”, with a quicker pace; here, moreover, the traditional concluding Gigue is omitted. By way of contrast, the Gigue of the great second Partita in D minor is followed by a further movement, the Chaconne. This was rather typical for keyboard Suites, and in fact this Partita seems to reveal a concept indebted to keyboard music.

The Chaconne is an extraordinary movement, whose exceptionality exceeds even the exceptionality of the whole set. It is a much longer movement than any other piece of the Suites or Partitas. It is more difficult than the most difficult of these extremely difficult pieces. It has a deep transcendental quality, which invites contemplation and awe, amazement and mystery. Musicologist Helga Thoene, in the early 2000s, has suggested that it might be a “Tombeau”, a post-mortem homage to the memory of Bach’s first wife, Maria Barbara. This is argued by Thoene on the basis of the presence of hidden chorale tunes within the texture of the piece. Their ordering suggests an itinerary of mourning and hope, of grief and hope. The first chorale is “Nobody can escape death”, a saddening but realistic consideration by all human beings. The second is a very human reaction to this: “How can I flee?”. This is echoed by a sequence of extremely quick scales, suggesting this impossible flight. Then Bach, a staunch believer, puts his sorrow in dialogue with Christ’s: “Jesus, I will meditate on thy Passion”. This opens up the way for one of the most enchanted and enchanting moments in music history, when the mode changes from minor to major and a flow of light fills the music. This corresponds to the Christmas chorale “From the highest I came down”: God’s response to human suffering is his Incarnation. Man’s answer is one of wonder: “How can I receive thee?”. And the result of that encounter is pure joy; the violin mimics a fanfare, a symbol for both festive happiness and resurrection. After that moment of elation, the mode turns again to the minor. Was it just a delusion? No: very sincerely and humanly, Bach suggests that believing in the resurrection does not eliminate the sorrow of mourning; rather, it transfigures it: “Thy will be done”, as the last chorale sings.

Together, these magnificent works constitute a crown on each violinist’s musical life; and Yulia Berinskaya’s performance enriches the discographic panorama with her unique and very personal insights.

CD1

01. Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001: I. Adagio

02. Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001: II. Fuga

03. Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001: III. Siciliana

04. Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001: IV. Presto

05. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 1, Allemanda

06. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 2, Double

07. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 3, Corrente

08. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 4, Double

09. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 5, Sarabande

10. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 6, Double

11. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 7, Tempo di Bourrée

12. Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: No. 8, Double

13. Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Minor, BWV 1003: I. Grave

14. Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Minor, BWV 1003: II. Fuga

15. Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Minor, BWV 1003: III. Andante

16. Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Minor, BWV 1003: IV. Allegro

CD2

01. Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: I. Allemanda

02. Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: II. Corrente

03. Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: III. Sarabanda

04. Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: IV. Giga

05. Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: V. Ciaccona

06. Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1005: I. Adagio

07. Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1005: II. Fuga

08. Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1005: III. Largo

09. Violin Sonata No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1005: IV. Allegro assai

10. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 1, Preludio

11. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 2, Loure

12. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 3, Gavotte en rondeau

13. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 4, Menuet I - Menuet II

14. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 5, Bourrée

15. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: No. 6, Gigue

Under many aspects, Bach was one of the greatest innovators in the history of music. Few things he created from scratch; but none of the elements he received from tradition he left untouched or adopted supinely. And one of the most impressive innovations that should be ascribed to his genius is the creation of a repertoire of unaccompanied works for the solo violin and cello, which demonstrates the possibility for these two instruments to sustain and support a whole musical discourse without the need of an accompaniment.

This is one of the cases where the “invention” of a form cannot be credited to Bach. Works for unaccompanied violin were not unheard-of at his time, although they constituted a niche repertoire. What Bach did was to elevate this possibility to previously unattained summits of artistry, as is abundantly demonstrated by the six masterpieces recorded here.

By its nature, the violin is an instrument which seems to require an accompaniment. Due to its physical conformation, and since geometry teaches us that no straight-line touches three non-aligned points, no more than two notes at a time can be logically played on it. If, in fact, the bow is a straight line, and the strings are seen (in their section) as non-aligned points, if follows that the maximum polyphony allowed on a violin is a diphony, the compresence of two notes. As a matter of fact, the situation is more complex than this. On the one hand, the bow is not a straight line: that is, it possesses some elasticity and flexibility, and therefore, depending on the pressure imparted by the performer, it is possible also to make three strings resound at the same time. Secondly, the possibility of arpeggiating chords (i.e. to play their notes in close sequence, so as to create the impression of simultaneity without actually producing it) is another resource available for composers. However, this kind of aural illusion works better with chords (i.e. harmonies) than with polyphony proper (i.e. counterpoint), because in order to perceive two melodic lines as such, as a true polyphony, they should be not just played, but also sustained at the same time. Bach brilliantly solves this problem by creating either subjects or countersubjects which have an important component of silence (through rests or staccatos), so as to allow the listener to experience some degree of fluidity without actually demanding it to the performer.

Bach united in his person a palette of skills which were, each per se, extremely rare. He was a very skilled violinist himself, although his favourite instrument was the organ. Still, he was extremely proficient in violin performance, and therefore knew perfectly well what a violin and a violinist can do, even though it was previously unheard-of or at least very unusual. He had a unique contrapuntal imagination (as is witnessed by his sons and pupils), which allowed him to deduce and understand the possibilities of a given subject in terms of polyphonic intertwining. He had great experience in the composition of dances, for solo instruments such as the keyboard up to large and even to orchestral ensembles. In short, nobody could have composed the Violin Sonatas and Partitas at the same level as he did.

In spite of this, these masterpieces remained dead letter for more than a century. Not only were they considered as too difficult to play, too complex technically and with almost unsurmountable issues; but they were also thought to be unrewarding, unfit for public performance, puzzling for listeners, incomplete, unsatisfactory. The most striking aspect is that view was held not only by people whose musical knowledge was superficial, but also by some of the finest musicians of the nineteenth century. Even more impressive is that some of them were among the most enthusiastic of Bach enthusiasts; they were among the promoters of the publication of Bach’s complete works, and among those supporting and fostering the public performance of his works.

Indeed, it was precisely with the goal in mind of disseminating these works, i.e. to promote their knowledge and “acceptability”, that musicians of the standing of Mendelssohn and Schumann realized what today seems a rather arbitrary undertaking, i.e. the creation of piano accompaniments for Bach’s unaccompanied violin masterpieces.

These piano accompaniments make explicit what the original scores had left implicit, i.e. a full harmonic texture and a complete polyphonic writing. In this fashion, the musical discourse is certainly easier to follow by the hearer, who is not required to work with his or her imagination as intensely as Bach’s original score asks for. When, in fact, there are gaps in the musical line, the kind of listening that music requires is very active; the listener’s imagination must supply for the missing lines.

It should also be added that these Sonatas and Partitas are no less demanding from the interpretive viewpoint than from the merely technical. Their extreme beauty requires exceptional understanding and skill of the interpreter; their undeniable spirituality invites a contemplative gaze on transcendence expressed through music; their texture requires extreme nuancing in terms of timbre, volume, bowing etc.

It can be said, therefore, that if these Solos represent a summit of compositional virtuosity (in Bach’s ability to create aural illusions, structuring full contrapuntal and harmonic writing for the unaccompanied violin), of performative virtuosity (in the extreme demands they pose to the interpreter), of interpretive virtuosity (in the high requirements to the musician’s understanding and rendition), but also – in a manner of speaking – of “listening virtuosity”. The ideal listener of these works is a “virtuoso listener”, one who knows how to listen, what to listen, and is happy to be involved in an arduous, demanding, but also very rewarding itinerary with the composer and the performer.

All this leads us to wonder who the intended performer and/or dedicatee of these works at the time of their composition was. No information has come to us; hypotheses involve an exceptionally gifted violinist, as yet unknown; a monarch or aristocrat who had at his or her service one such violinist and who may ask the performer to play them for him or her; or, perhaps most likely, Bach himself.

The number six was one particularly liked by Bach (and by many of his contemporaries) for collecting the best fruits of his creativity: there are six Brandenburg Concertos, six English Suites, six French Suites, six keyboard Partitas, six Cello Suites, and the Forty-Eight Preludes and Fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier are eight times six. It may be argued, therefore, that Bach had imagined the possibility of publishing these works; however, if this had been in his mind, he did not pursue this course of action. Among these six works, three are Sonatas, which follow the slow/quick/slow/quick scheme of the church Sonata (including the contrapuntal, fugato movements which characterize this particular genre). The other three, commonly called Partitas, were actually titled “Partie” (plural of Partia, a term commonly used at Bach’s time). As frequently happens with Bach, the pieces follow a harmonious ordering in terms of keys and modes; Sonatas and Partitas alternate with each other.

The “Partie” are suites of dances, and although Bach generally remains faithful to the traditional suite scheme which he employs in his other sets of suites, there are some notable exceptions and innovations. For example, the B-minor Partita is structured in pairs of movements: examples of the traditional dances of the suite are always followed by a variation, called “Double”, with a quicker pace; here, moreover, the traditional concluding Gigue is omitted. By way of contrast, the Gigue of the great second Partita in D minor is followed by a further movement, the Chaconne. This was rather typical for keyboard Suites, and in fact this Partita seems to reveal a concept indebted to keyboard music.

The Chaconne is an extraordinary movement, whose exceptionality exceeds even the exceptionality of the whole set. It is a much longer movement than any other piece of the Suites or Partitas. It is more difficult than the most difficult of these extremely difficult pieces. It has a deep transcendental quality, which invites contemplation and awe, amazement and mystery. Musicologist Helga Thoene, in the early 2000s, has suggested that it might be a “Tombeau”, a post-mortem homage to the memory of Bach’s first wife, Maria Barbara. This is argued by Thoene on the basis of the presence of hidden chorale tunes within the texture of the piece. Their ordering suggests an itinerary of mourning and hope, of grief and hope. The first chorale is “Nobody can escape death”, a saddening but realistic consideration by all human beings. The second is a very human reaction to this: “How can I flee?”. This is echoed by a sequence of extremely quick scales, suggesting this impossible flight. Then Bach, a staunch believer, puts his sorrow in dialogue with Christ’s: “Jesus, I will meditate on thy Passion”. This opens up the way for one of the most enchanted and enchanting moments in music history, when the mode changes from minor to major and a flow of light fills the music. This corresponds to the Christmas chorale “From the highest I came down”: God’s response to human suffering is his Incarnation. Man’s answer is one of wonder: “How can I receive thee?”. And the result of that encounter is pure joy; the violin mimics a fanfare, a symbol for both festive happiness and resurrection. After that moment of elation, the mode turns again to the minor. Was it just a delusion? No: very sincerely and humanly, Bach suggests that believing in the resurrection does not eliminate the sorrow of mourning; rather, it transfigures it: “Thy will be done”, as the last chorale sings.

Together, these magnificent works constitute a crown on each violinist’s musical life; and Yulia Berinskaya’s performance enriches the discographic panorama with her unique and very personal insights.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads