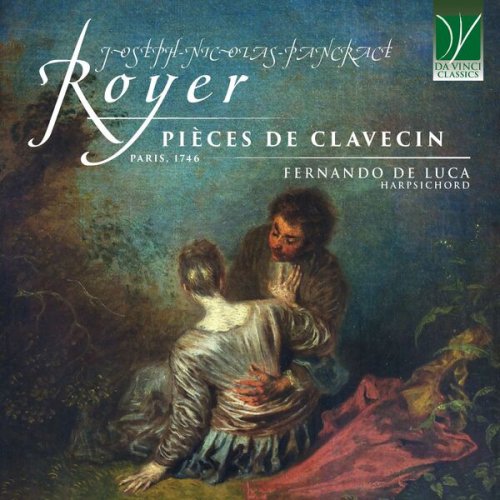

Fernando De Luca - Joseph-Nicolas-Pancrace Royer: Pièces de Clavecin, Paris, 1746 (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Fernando De Luca

- Title: Joseph-Nicolas-Pancrace Royer: Pièces de Clavecin, Paris, 1746

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Harpsichord

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:05:49

- Total Size: 384 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Pièces de clavecin: No. 1, La Majestueuse, courante

02. Pièces de clavecin: No. 2, La Zaïde, rondeau , Tendrement

03. Pièces de clavecin: No. 3, Les Matelots - Modérément

04. Pièces de clavecin: No. 4, 1er et 2e Tambourins, suite des Matelots

05. Pièces de clavecin: No. 5, L'Incertaine - Marqué

06. Pièces de clavecin: No. 6, L'Aimable, rondeau - Gracieux

07. Pièces de clavecin: No. 7, La Bagatelle

08. Pièces de clavecin: No. 8, Suitte de la Bagatelle

09. Pièces de clavecin: No. 9, La Rémouleuse, rondeau - Modérément

10. Pièces de clavecin: No. 10, Les tendres Sentiments, rondeau

11. Pièces de clavecin: No. 11, Le Vertigo, rondeau - Modérément

12. Pièces de clavecin: No. 12, Allemande

13. Pièces de clavecin: No. 13, La Sensible, rondeau

14. Pièces de clavecin: No. 14, La Marche des Scythes - Fièrement

The city of Turin, to the North-West of Italy, is the closest to France among the Italian cities. It is currently experiencing a cultural blossoming and is increasingly appreciated by tourists, because it has several distinguishing traits which are not found in other major Italian cities. Indeed, especially in certain zones of its historical centre, it does not look typically Italian. And this is understandable, since it has not been “Italian” for the longest part of its history. It is to the kings and princes of Turin, the Savoy, that Italy actually owes its existence as a nation, since it was thanks to the Savoy monarchy’s initiative and support that the Independence Wars of Italy were fought and ultimately won in the “Risorgimento”, the nineteenth century. But the official language at the Savoy court was French, and even today the dialect spoken in Turin is at least as close to French as it is to Italian.

It was within this context that Joseph-Nicolas-Pancrace Royer was born around 1705 or somewhat earlier. Although Royer was born in Turin, it is difficult to define it as a “Turinese” musician. For one thing, his family was quintessentially French (i.e., of what both at that time and today can be defined as “France”). His father was sent to Turin by the French king Louis XIV, who entrusted him with the responsibility of the gardens and fountains at the Savoy court. Thus did Royer happen to be born in Turin; however, his stay in the city which would become the first capital of Italy (before handing down the sceptre to Florence and to Rome) was to be very short. He was still a toddler when the family went back to Paris.

The family of an Intendant of the French Court was certainly rather well-to-do; for this reason, Royer’s first steps in the world of music were not intended as the beginnings of a future music professional, but only as a cultural refinement, a distinguished pastime for the child of a somewhat important family. Sadly, however, Royer’s father died when his son was just ten years old, and left him virtually destitute. On that occasion, what Royer had learnt as a budding musician became a valuable resource for earning a living. According to the Dictionnaire portatif des théâtres, dating from 1763, in his early twenties Royer was already being appreciated for his “knowledgeable and delicate way” in playing the harpsichord. His formative years in Paris positioned him well within the vibrant musical landscape of the early 18th century, where he absorbed the dominant traditions of French opera, sacred music, and instrumental composition.

From that same period are his first known compositions (where “known” is to be read as “that we know of”, since unfortunately they have not survived). They were Arias he wrote for two Opéras comiques by Alexis Piron, called respectively Le fâcheux veuvage (1725), performed at the Foire Saint-Laurent, and Crédit est mort (1726).

A few years later, in 1730, the first major success in the musical world came when he was appointed maître de musique at the Paris Opéra. This position allowed him to oversee productions and promote new works, including his own grand tragedy Pyrrhus (1730). The journal Le Mercure de France expressed its appreciation for the work, which “gave honor to both the poet and the musician for the beautiful pieces that are in it”. Notably, Royer’s tenure coincided with the controversial debut of Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), a work that revolutionized French opera and challenged the dominance of the Lullian tradition.

Beyond his administrative responsibilities, Royer became deeply involved in court music. He was named maître de musique des enfants de France, i.e. the music preceptor of the princes, sharing this prestigious role with Jean-Baptiste Matho. His duties included composing and directing music for the royal children, a position that placed him in close proximity to the Bourbon court and solidified his reputation as a composer of refinement and skill.

For the Dauphin he wrote a one-character short opera, on lines by J.-B. Rousseau which were considered as particularly challenging to be set to music; the Dauphin, who had by then just begun his musical education, surprised his sisters with his performance of the 45-minute solo work by Royer.

One of Royer’s most significant operatic achievements was Zaïde, reine de Grenade (1739), an ambitious tragédie lyrique that enjoyed considerable success. The opera was noted for its dramatic pacing, expressive orchestration, and virtuosic vocal writing. Its second act included an innovative hunting scene, lauded by contemporary critics as “the masterpiece of music in this genre.” Royer’s use of horns in F in this passage predated similar innovations by Rameau by six years, showcasing his forward-thinking orchestration.

Zaïde remained in the repertory and was constantly given for decades, performed in connection with royal nuptials in 1739, 1745, and 1770. The opera’s enduring appeal can be attributed to its compelling synthesis of dramatic tension, lyrical beauty, and grand choral writing. Royer’s ability to seamlessly integrate divertissements into the fabric of the narrative set him apart as a master of musical storytelling.

Another major work, Le pouvoir de l’amour (1743), demonstrated Royer’s continued commitment to French operatic traditions. He also worked on Pandore, a project based on a libretto by Voltaire, intended for the Dauphin’s wedding in 1745. However, it was abandoned in favor of a revival of Zaïde.

While Royer’s operatic works were well received, he was perhaps even more famous as a harpsichordist. M. A. Laugier, who left a book of memories titled Sentiment d’un harmoniphile sur différents ouvrages de musique, bears witness to Royer’s high fame as a performer of keyboard instruments (both the harpsichord ad the organs), and other contemporary accounts describe him as one of the most brilliant virtuosos of his time, rivaling the greatest French and Italian keyboardists.

In 1748, Royer was appointed director of the prestigious Concert Spirituel, a public concert series in Paris that featured both sacred and instrumental music. He obtained this (very well-paid) job in cooperation with violinist Gabriel Capperan, who was a court musician in turn. Under his leadership, the series flourished, introducing French audiences to a broader range of European compositions. He promoted the building of a new organ for the Palace des Tuileries, and its inauguration represented a momentous occasion for the new director. His tenure saw the first French performances of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater (1753), as well as symphonies by leading composers such as Carl Heinrich Graun, Johann Adolph Hasse, Niccolò Jommelli, and Johann Stamitz. Royer also undertook a revision of Jean Gilles’ Messe de Requiem (1750) and promoted Rameau’s grand motet In convertendo (1751).

His influence extended beyond programming: as inspecteur-général of the Paris Opéra from 1753, he played a key role in maintaining the high artistic standards of the institution. During this period, he worked on Prométhée et Pandore, on a libretto by Voltaire (which he had chosen to employ without the author’s explicit consent). However, the composer’s sudden death in January 1755 left the work incomplete. Voltaire, ever sharp-tongued, quipped that Royer had “sacrificed me to his semiquavers” but later conceded that “God wishes to have his soul and his music”.

It is again to the Sentiment d’un harmoniphile by Laugier that we owe another valuable piece of information. According to this account, after the composer’s death his heritage included unpublished harpsichord pieces sufficient, in number and quality, for compiling two volumes of keyboard music. However, sadly, only fifteen pieces, issued about ten years prior to his untimely death, survive to this day. In his dedicatory preface, addressed to the royal Princesses (à Mesdames de France), Royer wrote to his pupils: “It is taste which forms, enlivens, and rewards talent; and it is to taste only that they should pay homage. This reason leads me to make use of the permission you kindly accorded me, to offer you these Pièces de Clavecin”.

He then adds, for the profit of the reader: “Some of the pieces that I venture to present to the public having been disfigured and even published under other names, I have decided to have them engraved as I originally composed them. Those that appeared in several of my operas were only arranged as harpsichord pieces after they had been heard in the theatre. I have made no changes to the markings indicating appoggiaturas, cadences, and suspensions; I have merely indicated the repetitions by letters of the alphabet. It seems to me that this method is the most reliable for avoiding errors. These pieces allow for great variety, moving from tenderness to liveliness, from simplicity to grandeur, and this successively within the same piece. As for their execution, I leave it to the taste of those who do me the honor of playing them”.

In fact, within the collection of Royer’s harpsichord pieces some are excerpted from particularly famous pieces taken from his operas. Others depict characters or situations, as was usual in French harpsichord music of his time. His harpsichord works are his most lasting legacy, which has survived the test of time becoming a reference point for the French repertoire of the eighteenth century; in particular, the closing Marche des Scythes, with its impressive rhythmic drive and lively pulse has achieved immortality. Its unforgettable pace is a living testimony to its composer’s gifts and skill.

At the time of his death, Royer was widely respected both as a composer and a cultural leader. The Duke of Luynes praised him as a “very knowledgeable man, with an exceptional taste for melody.” His passing was marked by an elaborate memorial service, featuring Mondonville’s De profundis and Royer’s own adaptation of Gilles’ Requiem.

Despite his prominence in the mid-18th century, Royer’s music gradually faded from public consciousness, overshadowed by the works of Rameau and later Gluck. However, the rediscovery of his harpsichord music in the 20th and 21st centuries has led to renewed interest in his output. Royer’s keyboard style is characterized by bold harmonic progressions, rapid tirades (fast scalar passages), and a penchant for dramatic contrasts. His music frequently pushes the boundaries of harpsichord technique, demanding exceptional agility and expressivity from the performer.

As a composer, harpsichordist, and administrator, he left an indelible mark on the Parisian musical scene, influencing both his contemporaries and later generations. His music, vibrant and virtuosic, continues to captivate performers and audiences alike, securing his place among the great masters of the French Baroque.

01. Pièces de clavecin: No. 1, La Majestueuse, courante

02. Pièces de clavecin: No. 2, La Zaïde, rondeau , Tendrement

03. Pièces de clavecin: No. 3, Les Matelots - Modérément

04. Pièces de clavecin: No. 4, 1er et 2e Tambourins, suite des Matelots

05. Pièces de clavecin: No. 5, L'Incertaine - Marqué

06. Pièces de clavecin: No. 6, L'Aimable, rondeau - Gracieux

07. Pièces de clavecin: No. 7, La Bagatelle

08. Pièces de clavecin: No. 8, Suitte de la Bagatelle

09. Pièces de clavecin: No. 9, La Rémouleuse, rondeau - Modérément

10. Pièces de clavecin: No. 10, Les tendres Sentiments, rondeau

11. Pièces de clavecin: No. 11, Le Vertigo, rondeau - Modérément

12. Pièces de clavecin: No. 12, Allemande

13. Pièces de clavecin: No. 13, La Sensible, rondeau

14. Pièces de clavecin: No. 14, La Marche des Scythes - Fièrement

The city of Turin, to the North-West of Italy, is the closest to France among the Italian cities. It is currently experiencing a cultural blossoming and is increasingly appreciated by tourists, because it has several distinguishing traits which are not found in other major Italian cities. Indeed, especially in certain zones of its historical centre, it does not look typically Italian. And this is understandable, since it has not been “Italian” for the longest part of its history. It is to the kings and princes of Turin, the Savoy, that Italy actually owes its existence as a nation, since it was thanks to the Savoy monarchy’s initiative and support that the Independence Wars of Italy were fought and ultimately won in the “Risorgimento”, the nineteenth century. But the official language at the Savoy court was French, and even today the dialect spoken in Turin is at least as close to French as it is to Italian.

It was within this context that Joseph-Nicolas-Pancrace Royer was born around 1705 or somewhat earlier. Although Royer was born in Turin, it is difficult to define it as a “Turinese” musician. For one thing, his family was quintessentially French (i.e., of what both at that time and today can be defined as “France”). His father was sent to Turin by the French king Louis XIV, who entrusted him with the responsibility of the gardens and fountains at the Savoy court. Thus did Royer happen to be born in Turin; however, his stay in the city which would become the first capital of Italy (before handing down the sceptre to Florence and to Rome) was to be very short. He was still a toddler when the family went back to Paris.

The family of an Intendant of the French Court was certainly rather well-to-do; for this reason, Royer’s first steps in the world of music were not intended as the beginnings of a future music professional, but only as a cultural refinement, a distinguished pastime for the child of a somewhat important family. Sadly, however, Royer’s father died when his son was just ten years old, and left him virtually destitute. On that occasion, what Royer had learnt as a budding musician became a valuable resource for earning a living. According to the Dictionnaire portatif des théâtres, dating from 1763, in his early twenties Royer was already being appreciated for his “knowledgeable and delicate way” in playing the harpsichord. His formative years in Paris positioned him well within the vibrant musical landscape of the early 18th century, where he absorbed the dominant traditions of French opera, sacred music, and instrumental composition.

From that same period are his first known compositions (where “known” is to be read as “that we know of”, since unfortunately they have not survived). They were Arias he wrote for two Opéras comiques by Alexis Piron, called respectively Le fâcheux veuvage (1725), performed at the Foire Saint-Laurent, and Crédit est mort (1726).

A few years later, in 1730, the first major success in the musical world came when he was appointed maître de musique at the Paris Opéra. This position allowed him to oversee productions and promote new works, including his own grand tragedy Pyrrhus (1730). The journal Le Mercure de France expressed its appreciation for the work, which “gave honor to both the poet and the musician for the beautiful pieces that are in it”. Notably, Royer’s tenure coincided with the controversial debut of Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), a work that revolutionized French opera and challenged the dominance of the Lullian tradition.

Beyond his administrative responsibilities, Royer became deeply involved in court music. He was named maître de musique des enfants de France, i.e. the music preceptor of the princes, sharing this prestigious role with Jean-Baptiste Matho. His duties included composing and directing music for the royal children, a position that placed him in close proximity to the Bourbon court and solidified his reputation as a composer of refinement and skill.

For the Dauphin he wrote a one-character short opera, on lines by J.-B. Rousseau which were considered as particularly challenging to be set to music; the Dauphin, who had by then just begun his musical education, surprised his sisters with his performance of the 45-minute solo work by Royer.

One of Royer’s most significant operatic achievements was Zaïde, reine de Grenade (1739), an ambitious tragédie lyrique that enjoyed considerable success. The opera was noted for its dramatic pacing, expressive orchestration, and virtuosic vocal writing. Its second act included an innovative hunting scene, lauded by contemporary critics as “the masterpiece of music in this genre.” Royer’s use of horns in F in this passage predated similar innovations by Rameau by six years, showcasing his forward-thinking orchestration.

Zaïde remained in the repertory and was constantly given for decades, performed in connection with royal nuptials in 1739, 1745, and 1770. The opera’s enduring appeal can be attributed to its compelling synthesis of dramatic tension, lyrical beauty, and grand choral writing. Royer’s ability to seamlessly integrate divertissements into the fabric of the narrative set him apart as a master of musical storytelling.

Another major work, Le pouvoir de l’amour (1743), demonstrated Royer’s continued commitment to French operatic traditions. He also worked on Pandore, a project based on a libretto by Voltaire, intended for the Dauphin’s wedding in 1745. However, it was abandoned in favor of a revival of Zaïde.

While Royer’s operatic works were well received, he was perhaps even more famous as a harpsichordist. M. A. Laugier, who left a book of memories titled Sentiment d’un harmoniphile sur différents ouvrages de musique, bears witness to Royer’s high fame as a performer of keyboard instruments (both the harpsichord ad the organs), and other contemporary accounts describe him as one of the most brilliant virtuosos of his time, rivaling the greatest French and Italian keyboardists.

In 1748, Royer was appointed director of the prestigious Concert Spirituel, a public concert series in Paris that featured both sacred and instrumental music. He obtained this (very well-paid) job in cooperation with violinist Gabriel Capperan, who was a court musician in turn. Under his leadership, the series flourished, introducing French audiences to a broader range of European compositions. He promoted the building of a new organ for the Palace des Tuileries, and its inauguration represented a momentous occasion for the new director. His tenure saw the first French performances of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater (1753), as well as symphonies by leading composers such as Carl Heinrich Graun, Johann Adolph Hasse, Niccolò Jommelli, and Johann Stamitz. Royer also undertook a revision of Jean Gilles’ Messe de Requiem (1750) and promoted Rameau’s grand motet In convertendo (1751).

His influence extended beyond programming: as inspecteur-général of the Paris Opéra from 1753, he played a key role in maintaining the high artistic standards of the institution. During this period, he worked on Prométhée et Pandore, on a libretto by Voltaire (which he had chosen to employ without the author’s explicit consent). However, the composer’s sudden death in January 1755 left the work incomplete. Voltaire, ever sharp-tongued, quipped that Royer had “sacrificed me to his semiquavers” but later conceded that “God wishes to have his soul and his music”.

It is again to the Sentiment d’un harmoniphile by Laugier that we owe another valuable piece of information. According to this account, after the composer’s death his heritage included unpublished harpsichord pieces sufficient, in number and quality, for compiling two volumes of keyboard music. However, sadly, only fifteen pieces, issued about ten years prior to his untimely death, survive to this day. In his dedicatory preface, addressed to the royal Princesses (à Mesdames de France), Royer wrote to his pupils: “It is taste which forms, enlivens, and rewards talent; and it is to taste only that they should pay homage. This reason leads me to make use of the permission you kindly accorded me, to offer you these Pièces de Clavecin”.

He then adds, for the profit of the reader: “Some of the pieces that I venture to present to the public having been disfigured and even published under other names, I have decided to have them engraved as I originally composed them. Those that appeared in several of my operas were only arranged as harpsichord pieces after they had been heard in the theatre. I have made no changes to the markings indicating appoggiaturas, cadences, and suspensions; I have merely indicated the repetitions by letters of the alphabet. It seems to me that this method is the most reliable for avoiding errors. These pieces allow for great variety, moving from tenderness to liveliness, from simplicity to grandeur, and this successively within the same piece. As for their execution, I leave it to the taste of those who do me the honor of playing them”.

In fact, within the collection of Royer’s harpsichord pieces some are excerpted from particularly famous pieces taken from his operas. Others depict characters or situations, as was usual in French harpsichord music of his time. His harpsichord works are his most lasting legacy, which has survived the test of time becoming a reference point for the French repertoire of the eighteenth century; in particular, the closing Marche des Scythes, with its impressive rhythmic drive and lively pulse has achieved immortality. Its unforgettable pace is a living testimony to its composer’s gifts and skill.

At the time of his death, Royer was widely respected both as a composer and a cultural leader. The Duke of Luynes praised him as a “very knowledgeable man, with an exceptional taste for melody.” His passing was marked by an elaborate memorial service, featuring Mondonville’s De profundis and Royer’s own adaptation of Gilles’ Requiem.

Despite his prominence in the mid-18th century, Royer’s music gradually faded from public consciousness, overshadowed by the works of Rameau and later Gluck. However, the rediscovery of his harpsichord music in the 20th and 21st centuries has led to renewed interest in his output. Royer’s keyboard style is characterized by bold harmonic progressions, rapid tirades (fast scalar passages), and a penchant for dramatic contrasts. His music frequently pushes the boundaries of harpsichord technique, demanding exceptional agility and expressivity from the performer.

As a composer, harpsichordist, and administrator, he left an indelible mark on the Parisian musical scene, influencing both his contemporaries and later generations. His music, vibrant and virtuosic, continues to captivate performers and audiences alike, securing his place among the great masters of the French Baroque.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads