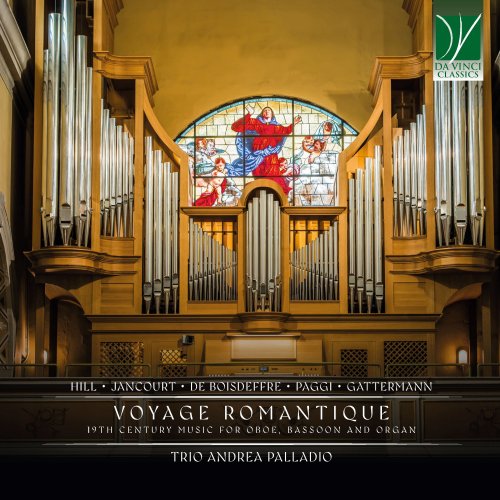

Trio Andrea Palladio - Voyage Romantique: 19th Century Music for Oboe, Bassoon and Organ (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Trio Andrea Palladio

- Title: Voyage Romantique: 19th Century Music for Oboe, Bassoon and Organ

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:10:50

- Total Size: 295 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Miniature Trio No. 2 in C Major: No. 1

02. Miniature Trio No. 2 in C Major: No.2. Andantino

03. Miniature Trio No. 2 in C Major: No.3. Minuetto, Allegretto

04. Miniature Trio No. 2 in C Major: No.4. Finale, Allegro

05. II Fantasia su Lucia di Lammermoor, Op. 27 (For Bassoon and Organ)

06. Poeme Pastoral, Op. 87: No.1. Matinée de Printemps, Allegro moderato

07. Poeme Pastoral, Op. 87: No.2. Angelus, Andantino

08. Poeme Pastoral, Op. 87: No.3. Sous Bois, Lent et expressif

09. Poeme Pastoral, Op. 87: No.4. Sur le Pré, Allegro ma non troppo

10. Souvenir de Bellini, Grande Fantaisie de concert, Op. 16 (For Oboe and Organ)

11. Fantasia Concertante, Op. 38

Musical talent is the combination of many factors, several of which are innate and unpredictable, whilst others are doubtlessly stimulated, if not outright caused, by early exposition to music and proper musical education. It is not infrequent, therefore, that great musicians come from a musical family. And this, once more, can have something to do with genes, but also with the opportunities a child is given by a musical family background. Similarly, children of musicians often receive musical tuition by their parents, at least in its basic form, and are normally oriented by their parents toward the most reliable institutes and teachers who can provide them with advanced education.

If this is the standard pattern, to which many famous musicians conform, there are also many variants. By chance or by design, the musicians featured in this Da Vinci Classics album have all rather atypical biographies, and represent therefore interesting and curious exceptions. Since most of them are little known today, these CD notes will focus mainly on their lives, in order to introduce their figures to the listener and thereby provide a suitable frame for the unique listening experience of this album.

The first composer featured here is Alfred Francis Hill, born in Australia, not far from Melbourne, on December 16th, 1869. His father, Charles, was by profession a hatter, but he played regularly and skillfully the violin. When Hill was still a small child, the family moved to Auckland in New Zealand, and after a few more years they moved once more to Wellington. Wherever they settled, the Hills quickly established musical practices which were to elicit the first sparks of interest in music in their son: singing together, playing together, producing and realizing performances where acting and music blended with each other. Rather soon, Alfred began to play the cornet, an instrument with which he was to participate in musical activities in his family, but also in a wind band and a theatrical company.

Given his talent, Alfred was invited to play for a touring operatic company’s orchestra, whose principal violinist instructed him in violin playing. It was evident that Alfred had a gift for composition too, but unfortunately the local resources did not allow him to receive a solid preparation for writing music. Alfred’s father, Charles, was however in favour of promoting his sons’ musical accomplishment; at the price of imaginable sacrifice, he sent both Alfred and his brother Jack to Europe, where they could find the most prestigious teachers of the time. They went to Leipzig, the city of Bach, of Mendelssohn, but also of Reinecke who was their contemporary. In fact, Reinecke accepted Hill as one of his orchestra violinists, while the young man – now aged 18 – continued his education at the Conservatory, where Reinecke himself also taught. His teachers were Gustav Schreck, who provided him with solid foundations for composition, and Hans Sitt for violin. The approach to composition Hill received in Leipzig was to constitute the foundational principle throughout his long career and life, regardless of the aesthetic turmoil of the first half of the twentieth century.

Some of Hill’s youthful works were performed in concert (including his Scotch sonata and an Air varié for violin and orchestra). Further recognition came with a prize for his accomplishment as one of the best students of the year.

Back in his adoptive home country, Hill was engaged as the conductor of the Wellington Orchestral Society, but his time there was war from idyllic. Many orchestra members grudged him his international studies, and, on the other hand, he quarreled with them over an incident involving a touring virtuoso whom Hill considered as a charlatan and did not wish to invite.

Hill then began to pay increasing attention to the musical heritage of the Māori and to their unique culture, incorporating elements of it in his own compositions after having collected and transcribed their songs. Hill settled in Sydney with his first wife, Sarah Brownhill Booth, and began a career in the field of operetta; his A Moorish Maid was particularly successful. But it was a particular song based on Māori models which was to become his most celebrated work: Waiata poi was to be sung and recorded by leading musicians for years. Hill also founded the first professional orchestra in New Zealand, but, after its dissolution, he returned to Australia and earned his living with playing and composing. Another important foundation was that of the Australian Opera League in Sydney; in 1916, Hill became the first professor of harmony and composition at the newly founded New South Wales State Conservatorium of Music. Eighteen years later, Hill would establish a music academy of his own. In the meantime, having divorced his first wife, Hill married a former pupil of his, Mirrie Solomon.

Along with Māori music, Hill consecrated his attention also to Australian aboriginal music, here too incorporating it within his own works. He died, at a ripe old age, in 1960.

If Hill transitioned from the cornet to the violin, Eugène Louis-Marie Jancourt had an almost complementary “conversion” in his life. Born in Château-Thierry, in France, on December 15th, 1815, he came from a musical family; his first instruments were the violin and the clarinet, but later he was fascinated by the bassoon, by its timbre and personality, and adopted the instrument of which he would eventually become one of the leading virtuosos of his time.

Similar to Hill, Jancourt did not attend Conservatory before what is normally considered as too old an age for musical studies – in his case, he enrolled at nineteen. In spite of this, both quickly reached proficiency, as demonstrated by his earning the Premier Prix in bassoon after just two years at conservatory. His teacher, François-René Gebauer, gave him one of his bassoons, having noticed the inadequacy of the instrument Jancourt was playing.

Having graduated from Conservatoire, Jancourt began his professional career as a bassoonist, at first as a freelance musician, and then at the Opéra-Comique, where he became the principal bassoonist, later to be followed by an appointment at the Théâtre Italien. He also began his activity as a composer, promoting a new perspective on his instrument: he was one of the first who intuited the bassoon’s potential as a solo instrument, and he demonstrated its possibilities by his own playing.

When his career as a performer ended, he became an appreciated professor at the Conservatoire, until his retirement in 1891; ten years later, he would pass away. He has also an historical importance as an author of treatises and methods for the bassoon, as well as for his cooperation in the creation of the Buffet-style bassoon – a more modern, improved instrument. His compositional output is mainly constituted by works which involve his instrument, either solo or in chamber music.

Much shorter was the life of René de Boisdeffre, who came from a family of military people: his grandfather had been a general in Napoleon’s army. René’s mother, Charlotte Cailloux, was a salon pianist and singer, and he was introduced to music by her. However – in this case due to his well-to-do social position – Boisdeffre was not to receive a standard musical education. He did not attend Conservatory, and – even though music was his life – he remained an “amateur” for his entire life.

He was born in Vesoul but soon moved to Paris with his family; he studied piano with Charles Wagner and composition with Auguste Barberau. His talent and skills were soon recognized, as is demonstrated by the immediate publication of all his works by the publishing company Brandus.

His main interests lay in the field of chamber music; his first important success came with his Piano Quintet op. 11 (1872), which brought him fame and recognition; several of his later works were to receive important official acknowledgments, such as the Chartier Prix, the award of the Société des compositeurs de musique, and, last but by no means least, the knighthood in the Legion d’honneur. His output comprises also some high-quality religious music, including oratorios and Masses, as well as symphonic works.

His contemporary Giovanni Paggi was a native of Jesi, a city in the Italian region of Marche, and his first musical education took place in his hometown. His instruments were the oboe and English horn, and, after his successful debut in the city of Perugia, aged 22, he decided to seek fortune in Rome. The atmosphere of the “eternal city” proved favourable to his talents and skills, and brought him numerous engagements in the most important Italian cities and theatres, but also abroad, in a truly international dimension. In fact, he spent more than ten years in America, where he gained unanimous recognition. American newspapers praised the “power, grace, expression, divine song” which he was able to draw from his instrument and which “made him unique” among his peers. Back in his home country, he resumed his dazzling career, both in Italy and in the other European countries, eliciting the interest of public, critics, and press. As a token of the professionals’ appreciation, he was elected a member of numerous and prestigious Academies. He spent his last years in Florence, where he died in 1887, aged 81.

Very scanty information remains, instead, about the biographical details of flutist and composer Philippe Gattermann. His birth date has been inferred by Tom Moore as about 1815, given the times of his first documented performances (in 1835); some confusion arises also from the fact that he shared the initial letter of his first name with his father, Prosper. Gattermann began to issue works for the flute, which was his instrument, but also for the cornet and piano in the early 1840s. It seems that Gattermann was not bound to any particular orchestra, and, furthermore, that he did not write virtuoso concertos for the flute. His name appears frequently as a partner of other musicians in the Parisian academies, and also as a conductor (e.g. directing the Parisian Société Philharmonique in 1846). It appears that at some time around 1850 he moved to Marseille, but then his traces start to become more elusive, and even his death date can only be inferred.

Together, these composers showcase the fecundity of the interaction between two “blown” wind instruments (woodwinds) such as the oboe and the bassoon, and a “keyboard wind instrument”, as the organ; a fascinating blend which lends itself to the evocation of many orchestral timbres, as well as of the human voice, appearing as if in transparency behind the numerous operatic paraphrases presented here.

01. Miniature Trio No. 2 in C Major: No. 1

02. Miniature Trio No. 2 in C Major: No.2. Andantino

03. Miniature Trio No. 2 in C Major: No.3. Minuetto, Allegretto

04. Miniature Trio No. 2 in C Major: No.4. Finale, Allegro

05. II Fantasia su Lucia di Lammermoor, Op. 27 (For Bassoon and Organ)

06. Poeme Pastoral, Op. 87: No.1. Matinée de Printemps, Allegro moderato

07. Poeme Pastoral, Op. 87: No.2. Angelus, Andantino

08. Poeme Pastoral, Op. 87: No.3. Sous Bois, Lent et expressif

09. Poeme Pastoral, Op. 87: No.4. Sur le Pré, Allegro ma non troppo

10. Souvenir de Bellini, Grande Fantaisie de concert, Op. 16 (For Oboe and Organ)

11. Fantasia Concertante, Op. 38

Musical talent is the combination of many factors, several of which are innate and unpredictable, whilst others are doubtlessly stimulated, if not outright caused, by early exposition to music and proper musical education. It is not infrequent, therefore, that great musicians come from a musical family. And this, once more, can have something to do with genes, but also with the opportunities a child is given by a musical family background. Similarly, children of musicians often receive musical tuition by their parents, at least in its basic form, and are normally oriented by their parents toward the most reliable institutes and teachers who can provide them with advanced education.

If this is the standard pattern, to which many famous musicians conform, there are also many variants. By chance or by design, the musicians featured in this Da Vinci Classics album have all rather atypical biographies, and represent therefore interesting and curious exceptions. Since most of them are little known today, these CD notes will focus mainly on their lives, in order to introduce their figures to the listener and thereby provide a suitable frame for the unique listening experience of this album.

The first composer featured here is Alfred Francis Hill, born in Australia, not far from Melbourne, on December 16th, 1869. His father, Charles, was by profession a hatter, but he played regularly and skillfully the violin. When Hill was still a small child, the family moved to Auckland in New Zealand, and after a few more years they moved once more to Wellington. Wherever they settled, the Hills quickly established musical practices which were to elicit the first sparks of interest in music in their son: singing together, playing together, producing and realizing performances where acting and music blended with each other. Rather soon, Alfred began to play the cornet, an instrument with which he was to participate in musical activities in his family, but also in a wind band and a theatrical company.

Given his talent, Alfred was invited to play for a touring operatic company’s orchestra, whose principal violinist instructed him in violin playing. It was evident that Alfred had a gift for composition too, but unfortunately the local resources did not allow him to receive a solid preparation for writing music. Alfred’s father, Charles, was however in favour of promoting his sons’ musical accomplishment; at the price of imaginable sacrifice, he sent both Alfred and his brother Jack to Europe, where they could find the most prestigious teachers of the time. They went to Leipzig, the city of Bach, of Mendelssohn, but also of Reinecke who was their contemporary. In fact, Reinecke accepted Hill as one of his orchestra violinists, while the young man – now aged 18 – continued his education at the Conservatory, where Reinecke himself also taught. His teachers were Gustav Schreck, who provided him with solid foundations for composition, and Hans Sitt for violin. The approach to composition Hill received in Leipzig was to constitute the foundational principle throughout his long career and life, regardless of the aesthetic turmoil of the first half of the twentieth century.

Some of Hill’s youthful works were performed in concert (including his Scotch sonata and an Air varié for violin and orchestra). Further recognition came with a prize for his accomplishment as one of the best students of the year.

Back in his adoptive home country, Hill was engaged as the conductor of the Wellington Orchestral Society, but his time there was war from idyllic. Many orchestra members grudged him his international studies, and, on the other hand, he quarreled with them over an incident involving a touring virtuoso whom Hill considered as a charlatan and did not wish to invite.

Hill then began to pay increasing attention to the musical heritage of the Māori and to their unique culture, incorporating elements of it in his own compositions after having collected and transcribed their songs. Hill settled in Sydney with his first wife, Sarah Brownhill Booth, and began a career in the field of operetta; his A Moorish Maid was particularly successful. But it was a particular song based on Māori models which was to become his most celebrated work: Waiata poi was to be sung and recorded by leading musicians for years. Hill also founded the first professional orchestra in New Zealand, but, after its dissolution, he returned to Australia and earned his living with playing and composing. Another important foundation was that of the Australian Opera League in Sydney; in 1916, Hill became the first professor of harmony and composition at the newly founded New South Wales State Conservatorium of Music. Eighteen years later, Hill would establish a music academy of his own. In the meantime, having divorced his first wife, Hill married a former pupil of his, Mirrie Solomon.

Along with Māori music, Hill consecrated his attention also to Australian aboriginal music, here too incorporating it within his own works. He died, at a ripe old age, in 1960.

If Hill transitioned from the cornet to the violin, Eugène Louis-Marie Jancourt had an almost complementary “conversion” in his life. Born in Château-Thierry, in France, on December 15th, 1815, he came from a musical family; his first instruments were the violin and the clarinet, but later he was fascinated by the bassoon, by its timbre and personality, and adopted the instrument of which he would eventually become one of the leading virtuosos of his time.

Similar to Hill, Jancourt did not attend Conservatory before what is normally considered as too old an age for musical studies – in his case, he enrolled at nineteen. In spite of this, both quickly reached proficiency, as demonstrated by his earning the Premier Prix in bassoon after just two years at conservatory. His teacher, François-René Gebauer, gave him one of his bassoons, having noticed the inadequacy of the instrument Jancourt was playing.

Having graduated from Conservatoire, Jancourt began his professional career as a bassoonist, at first as a freelance musician, and then at the Opéra-Comique, where he became the principal bassoonist, later to be followed by an appointment at the Théâtre Italien. He also began his activity as a composer, promoting a new perspective on his instrument: he was one of the first who intuited the bassoon’s potential as a solo instrument, and he demonstrated its possibilities by his own playing.

When his career as a performer ended, he became an appreciated professor at the Conservatoire, until his retirement in 1891; ten years later, he would pass away. He has also an historical importance as an author of treatises and methods for the bassoon, as well as for his cooperation in the creation of the Buffet-style bassoon – a more modern, improved instrument. His compositional output is mainly constituted by works which involve his instrument, either solo or in chamber music.

Much shorter was the life of René de Boisdeffre, who came from a family of military people: his grandfather had been a general in Napoleon’s army. René’s mother, Charlotte Cailloux, was a salon pianist and singer, and he was introduced to music by her. However – in this case due to his well-to-do social position – Boisdeffre was not to receive a standard musical education. He did not attend Conservatory, and – even though music was his life – he remained an “amateur” for his entire life.

He was born in Vesoul but soon moved to Paris with his family; he studied piano with Charles Wagner and composition with Auguste Barberau. His talent and skills were soon recognized, as is demonstrated by the immediate publication of all his works by the publishing company Brandus.

His main interests lay in the field of chamber music; his first important success came with his Piano Quintet op. 11 (1872), which brought him fame and recognition; several of his later works were to receive important official acknowledgments, such as the Chartier Prix, the award of the Société des compositeurs de musique, and, last but by no means least, the knighthood in the Legion d’honneur. His output comprises also some high-quality religious music, including oratorios and Masses, as well as symphonic works.

His contemporary Giovanni Paggi was a native of Jesi, a city in the Italian region of Marche, and his first musical education took place in his hometown. His instruments were the oboe and English horn, and, after his successful debut in the city of Perugia, aged 22, he decided to seek fortune in Rome. The atmosphere of the “eternal city” proved favourable to his talents and skills, and brought him numerous engagements in the most important Italian cities and theatres, but also abroad, in a truly international dimension. In fact, he spent more than ten years in America, where he gained unanimous recognition. American newspapers praised the “power, grace, expression, divine song” which he was able to draw from his instrument and which “made him unique” among his peers. Back in his home country, he resumed his dazzling career, both in Italy and in the other European countries, eliciting the interest of public, critics, and press. As a token of the professionals’ appreciation, he was elected a member of numerous and prestigious Academies. He spent his last years in Florence, where he died in 1887, aged 81.

Very scanty information remains, instead, about the biographical details of flutist and composer Philippe Gattermann. His birth date has been inferred by Tom Moore as about 1815, given the times of his first documented performances (in 1835); some confusion arises also from the fact that he shared the initial letter of his first name with his father, Prosper. Gattermann began to issue works for the flute, which was his instrument, but also for the cornet and piano in the early 1840s. It seems that Gattermann was not bound to any particular orchestra, and, furthermore, that he did not write virtuoso concertos for the flute. His name appears frequently as a partner of other musicians in the Parisian academies, and also as a conductor (e.g. directing the Parisian Société Philharmonique in 1846). It appears that at some time around 1850 he moved to Marseille, but then his traces start to become more elusive, and even his death date can only be inferred.

Together, these composers showcase the fecundity of the interaction between two “blown” wind instruments (woodwinds) such as the oboe and the bassoon, and a “keyboard wind instrument”, as the organ; a fascinating blend which lends itself to the evocation of many orchestral timbres, as well as of the human voice, appearing as if in transparency behind the numerous operatic paraphrases presented here.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads