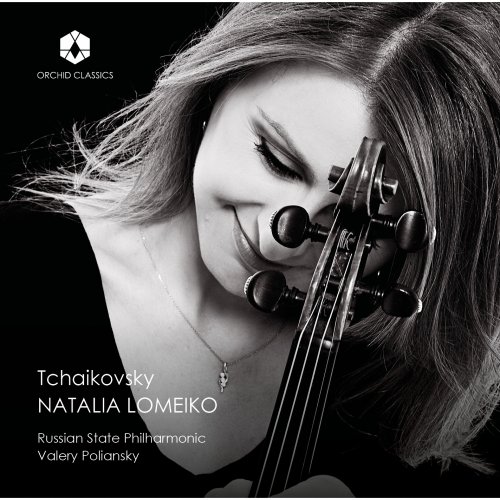

Natalia Lomeiko, The Russian State Philharmonic & Valery Polyansky - Tchaikovsky (2025) Hi-Res

BAND/ARTIST: Natalia Lomeiko, The Russian State Philharmonic, Valery Polyansky

- Title: Tchaikovsky

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Orchid Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks) / FLAC 24 Bit (96 KHz / tracks)

- Total Time: 71:43 min

- Total Size: 337 MB / 1,1 GB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

Violin Concerto in D major, Op.35

1. I Allegro moderato

2. II Canzonetta

3. III Finale

Souvenir d’un lieu cher, Op.42

4. I Meditation

5. II Scherzo

6. III Melody

7. Sérénade mélancolique, Op.26

8. Valse-Scherzo, Op.34

Violin Concerto in D major, Op.35

1. I Allegro moderato

2. II Canzonetta

3. III Finale

Souvenir d’un lieu cher, Op.42

4. I Meditation

5. II Scherzo

6. III Melody

7. Sérénade mélancolique, Op.26

8. Valse-Scherzo, Op.34

Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, Op.35 of 1878 had a rather tumultuous journey from the work’s conception to the popularity it enjoys today. Tchaikovsky completed the first sketches very quickly while holidaying in the Swiss resort of Clarens on the shores of Lake Geneva. The intended dedicatee was the young violinist Iosif Kotek, a former student of Tchaikovsky’s at the Moscow Conservatory who was greatly admired by the composer; it is possible that they were conducting a clandestine relationship. Kotek also mediated between Tchaikovsky and Nadhezha von Meck, who would become his patroness and confidante, during the early stages of their acquaintance. He was not sufficiently well known to premiere the concerto, however, so Tchaikovsky approached Leopold Auer to be its dedicatee. Auer was sniffy, dismissing the piece as “unviolinistic” and only revising his opinion in the last year of the composer’s life. Eventually, Adolph Brodsky premiered the Violin Concerto in Vienna in 1881, but its early success was hindered when the influential critic Eduard Hanslick denounced it with considerable vehemence. Thankfully, it has outlived the criticism, and remains one of Tchaikovsky’s best-loved pieces.

Kotek played through segments of the concerto as it was written and may have inspired or influenced its composition. The first movement is based on two melodies that are explored and developed by both soloist and orchestra. The model of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto is also evident in the placing of the cadenza at the end of the central section before the main themes are reprised. The slow movement’s introduction delays the entrance of the main melody, which has all the more impact when it arrives. Its title, ‘Canzonetta’, means a type of vocal movement, highlighting the singing nature of the violin part. The finale begins with a long introduction after which the main melody fizzes along. This is contrasted with a reference to one of Tchaikovsky’s operas, Eugene Onegin; the oboe – used for the same purpose in the opera – plays a theme that evokes Tatyana, the opera’s tragic heroine. This does little to diminish the overall merriment of the finale, however; the violin writing is scintillating, and the work ends in high spirits.

The ‘Canzonetta’ was not Tchaikovsky’s first choice for the central movement of his Violin Concerto. While still at Clarens, in March 1878, he composed a ‘Méditation’ intended as the concerto’s slow movement, but on realising that it was too long in that context he set it aside and wrote the ‘Canzonetta’. The ‘Méditation’, reworked for violin and piano, became the first movement of the Souvenir d’un lieu cher (Memory of a dear place) – but it was not Clarens to which Tchaikovsky was paying tribute. He made a start on the work when back in Russia, in May 1878, before heading to his patroness Nadezhda von Meck’s Ukrainian country estate in Brailivo (or Brailovo, known today as Brailiv), finishing the work by the end of May and dedicating it to ‘B*******’ (almost certainly the place itself), making von Meck a present of the original manuscript. This is Tchaikovsky’s only known piece originally written for violin and piano (apart from the opening movement), but it has become well known in the version for violin and orchestra arranged by Alexander Glazunov. As with his more famous Souvenir de Florence for strings (1891-92), Tchaikovsky created a musical postcard or photo album as a means of remembering and celebrating a much-loved retreat.

The work opens with the ‘Méditation’, but anyone expecting something as dreamy as the 1894 piece of the same name by Massenet will soon find that Tchaikovsky’s interpretation of the word is not as a gentle reverie, but a complex train of thought. The violin’s poignant and impassioned material in the lower register is reprised after a gentler central section, but the coda features a subtle shift from D minor to D major during the violin line’s exquisite ascent into the ether. The Scherzo starts and ends with skittish, almost nervous energy framing a passage of sunny, song-like charm, and the ‘Mélodie’ is justly famous for its tender melody and sweetly nostalgic harmonies, concluding with a brief coda of irresistible tenderness.

Before Tchaikovsky and Auer fell out over the Violin Concerto, the violinist had inspired the composer to write another piece, the Sérénade mélancolique. In 1874 Tchaikovsky heard a public performance by Auer, which he praised in a review for its “great expressivity, the thoughtful finesse and poetry of the interpretation”. Both men attended a party given by Nikolai Rubinstein in January 1875, and it is possible that they discussed a new piece on that occasion – some accounts suggest that Auer commissioned the Sérénade from Tchaikovsky, others that he composed it off his own bat. Either way, in February Tchaikovsky wrote to his brother, Modest: “I have finished my Piano Concerto” – his first – “and have already written a violin piece I have promised to Auer”. But, as with the Violin Concerto, Auer did not give the work’s premiere – and, as with that concerto, it was Brodsky who did, in January 1876. Auer did however perform the work later the same year, during its first outing in St Petersburg.

The Sérénade begins with an atmospheric orchestral introduction, setting the scene for the violin’s first, folk-like entry, played entirely on the G string. A new theme unfolds, related to the woodwind opening, before an animated middle section that subsides into an introspective violin cadenza. The opening section is reprised, with a call-back to the very first bars during the coda, at the end of which the violin is given one last moment to reflect before the music fades into nothingness.

In the following year, 1877, Tchaikovsky built up to the writing of his Violin Concerto with another work composed for Kotek, the Valse-Scherzo. This time Kotek was the dedicatee, and his letters imply that he assisted with the work’s orchestration, although Tchaikovsky’s letters do not corroborate this. Nikolai Rubinstein conducted the piece’s premiere, which was given by one of Kotek’s fellow students at the Moscow Conservatory, Polish violinist Stanisław Barcewicz. The Valse-Scherzo was published in 1878 for violin and piano, an arrangement presumably considered more commercially viable by the publishing house; the orchestral version was not released until 1895, after Tchaikovsky’s death.

Tchaikovsky was particularly skilful at writing waltzes – his Symphony No.6 even includes a ‘limping’ waltz in 5/4 time – but this example reveals a different facet of his approach to the dance style, with less emphasis on swirling grace and more on the joyously unbuttoned nature of the violin writing, which has the folk-like freedom of gypsy music. There is a virtuosic central cadenza full of flashy display before the joie de vivre of the opening returns, punctuated by the orchestra’s witty woodwinds and popping pizzicato. The tragedy of Tchaikovsky’s life often casts a shadow over his music, but the Valse-Scherzo is a joy because for once there is not a cloud in sight, just blue sky, and sunshine.

Kotek played through segments of the concerto as it was written and may have inspired or influenced its composition. The first movement is based on two melodies that are explored and developed by both soloist and orchestra. The model of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto is also evident in the placing of the cadenza at the end of the central section before the main themes are reprised. The slow movement’s introduction delays the entrance of the main melody, which has all the more impact when it arrives. Its title, ‘Canzonetta’, means a type of vocal movement, highlighting the singing nature of the violin part. The finale begins with a long introduction after which the main melody fizzes along. This is contrasted with a reference to one of Tchaikovsky’s operas, Eugene Onegin; the oboe – used for the same purpose in the opera – plays a theme that evokes Tatyana, the opera’s tragic heroine. This does little to diminish the overall merriment of the finale, however; the violin writing is scintillating, and the work ends in high spirits.

The ‘Canzonetta’ was not Tchaikovsky’s first choice for the central movement of his Violin Concerto. While still at Clarens, in March 1878, he composed a ‘Méditation’ intended as the concerto’s slow movement, but on realising that it was too long in that context he set it aside and wrote the ‘Canzonetta’. The ‘Méditation’, reworked for violin and piano, became the first movement of the Souvenir d’un lieu cher (Memory of a dear place) – but it was not Clarens to which Tchaikovsky was paying tribute. He made a start on the work when back in Russia, in May 1878, before heading to his patroness Nadezhda von Meck’s Ukrainian country estate in Brailivo (or Brailovo, known today as Brailiv), finishing the work by the end of May and dedicating it to ‘B*******’ (almost certainly the place itself), making von Meck a present of the original manuscript. This is Tchaikovsky’s only known piece originally written for violin and piano (apart from the opening movement), but it has become well known in the version for violin and orchestra arranged by Alexander Glazunov. As with his more famous Souvenir de Florence for strings (1891-92), Tchaikovsky created a musical postcard or photo album as a means of remembering and celebrating a much-loved retreat.

The work opens with the ‘Méditation’, but anyone expecting something as dreamy as the 1894 piece of the same name by Massenet will soon find that Tchaikovsky’s interpretation of the word is not as a gentle reverie, but a complex train of thought. The violin’s poignant and impassioned material in the lower register is reprised after a gentler central section, but the coda features a subtle shift from D minor to D major during the violin line’s exquisite ascent into the ether. The Scherzo starts and ends with skittish, almost nervous energy framing a passage of sunny, song-like charm, and the ‘Mélodie’ is justly famous for its tender melody and sweetly nostalgic harmonies, concluding with a brief coda of irresistible tenderness.

Before Tchaikovsky and Auer fell out over the Violin Concerto, the violinist had inspired the composer to write another piece, the Sérénade mélancolique. In 1874 Tchaikovsky heard a public performance by Auer, which he praised in a review for its “great expressivity, the thoughtful finesse and poetry of the interpretation”. Both men attended a party given by Nikolai Rubinstein in January 1875, and it is possible that they discussed a new piece on that occasion – some accounts suggest that Auer commissioned the Sérénade from Tchaikovsky, others that he composed it off his own bat. Either way, in February Tchaikovsky wrote to his brother, Modest: “I have finished my Piano Concerto” – his first – “and have already written a violin piece I have promised to Auer”. But, as with the Violin Concerto, Auer did not give the work’s premiere – and, as with that concerto, it was Brodsky who did, in January 1876. Auer did however perform the work later the same year, during its first outing in St Petersburg.

The Sérénade begins with an atmospheric orchestral introduction, setting the scene for the violin’s first, folk-like entry, played entirely on the G string. A new theme unfolds, related to the woodwind opening, before an animated middle section that subsides into an introspective violin cadenza. The opening section is reprised, with a call-back to the very first bars during the coda, at the end of which the violin is given one last moment to reflect before the music fades into nothingness.

In the following year, 1877, Tchaikovsky built up to the writing of his Violin Concerto with another work composed for Kotek, the Valse-Scherzo. This time Kotek was the dedicatee, and his letters imply that he assisted with the work’s orchestration, although Tchaikovsky’s letters do not corroborate this. Nikolai Rubinstein conducted the piece’s premiere, which was given by one of Kotek’s fellow students at the Moscow Conservatory, Polish violinist Stanisław Barcewicz. The Valse-Scherzo was published in 1878 for violin and piano, an arrangement presumably considered more commercially viable by the publishing house; the orchestral version was not released until 1895, after Tchaikovsky’s death.

Tchaikovsky was particularly skilful at writing waltzes – his Symphony No.6 even includes a ‘limping’ waltz in 5/4 time – but this example reveals a different facet of his approach to the dance style, with less emphasis on swirling grace and more on the joyously unbuttoned nature of the violin writing, which has the folk-like freedom of gypsy music. There is a virtuosic central cadenza full of flashy display before the joie de vivre of the opening returns, punctuated by the orchestra’s witty woodwinds and popping pizzicato. The tragedy of Tchaikovsky’s life often casts a shadow over his music, but the Valse-Scherzo is a joy because for once there is not a cloud in sight, just blue sky, and sunshine.

| Classical | FLAC / APE | HD & Vinyl

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads