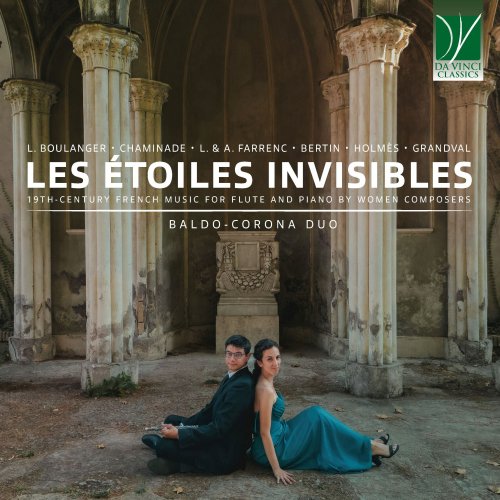

Baldo-Corona duo, Davide Baldo, Chiara Corona - Les Étoiles Invisibles, 19th-Century French Music for Flute and Piano by Women Composers (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Baldo-Corona duo, Davide Baldo, Chiara Corona

- Title: Les Étoiles Invisibles, 19th-Century French Music for Flute and Piano by Women Composers

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:57:36

- Total Size: 222 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. D'un matin de printemps

02. Sérénade aux étoiles, Op. 142

03. Air vaudois, Op. 108

04. Venez dans la prairie. 3ème Rondoletto sur la chansonnette de Dolive

05. Variations concertantes sur la tyrolienne de Me Gail, Op. 22: Celui qui sut toucher mon coeur

06. Le Loup-garou (Opéra comique en 1 acte)

07. Trois petites pièces: No. 1, Chanson

08. Trois petites pièces: No. 2, Clair de lune

09. Trois petites pièces: No. 3, Gigue

10. Suite pour flûte et piano: No. 1, Prélude

11. Suite pour flûte et piano: No. 2, Scherzo

12. Suite pour flûte et piano: No. 3, Menuet

13. Suite pour flûte et piano: No. 4, Romance

14. Suite pour flûte et piano: No. 5, Final

Among the many curiosities of classical music, several of which are rooted in, and justified by, the history of music, there is the “gendered” nature of some musical instruments. Most instruments are played today, and/or were played in the past, indifferently by men and women (although the actual possibilities of becoming professional players of that instrument were obviously different for men and women). Others are, or were, typically played by males or females, with a few instruments undergoing a “shift” in gender connotations through the ages. For an example of an instrument which was traditionally played by men only, and that even today is played overwhelmingly by men, the tuba is typical. In this case, there are also objective reasons for such a phenomenon, since the tuba is heavy to carry, and requires extra powerful lungs to be played; generally, therefore, the physical conformation of men makes them more “fit” to play such a physically demanding instrument. In other cases, an instrument was played in the past by both men and women, but today is more typically played by ladies – the harp is paradigmatic under this viewpoint. In the nineteenth century, for another example, amateur piano players were mostly female, although professional concert players were gentlemen or ladies indifferently. In still other cases, there are no physical reasons for a particular preference; rather, the higher percentage of male or female players for a specific instrument is due more to aesthetical reasons. A certain instrument is seen as more apt to symbolize the qualities traditionally associated with femininity or masculinity. And this is not without effects in the creation of new repertoire; there is in fact a hermeneutical circle by virtue of which the alleged gendered qualities of an instrument tend to be expressed in the music for that instrument, thus causing in turn a particular affinity between male or female players and that repertoire.

The flute, which is the coprotagonist – along with the piano – of this Da Vinci Classics album, is an instrument which is considered as having a certain “femininity”; although, obviously, there are excellent flutists of both sexes, this instrument still seems to attract a special attention from ladies, and so it was in the past. This album encompasses works for flute and piano written by female composers who lived in France between nineteenth and twentieth century. Their biographies, although very different under some aspects, have however some points in common which will be presently pointed out.

As concerns their birth dates, Louise Farrenc was born in 1804; Louise-Angélique Bertin in 1805; Clémence de Grandval in 1828; Augusta Holmès in 1847; Cécile Chaminade in 1857; Mel Bonis in 1858; and Lili Boulanger in 1893, thus encompassing the entire nineteenth century. Chaminade died at 86, in 1944; Grandval and Bonis both died at age 79; Bertin at 72; Farrenc at 71; Holmès at 56; whilst the youngest of this selection, Lili Boulanger, died at barely 25, outlived by a quarter of century by Chaminade; however, in spite of her extremely short life, Boulanger left a deep mark in the history of music.

As concerns their families, several of them came from musicians’ families. Boulanger was the sister of another very famed female musician, Nadia; their parents were a composer (Ernest, who won the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1835) and a Russian singer. Chaminade also came from a musical family, receiving her first piano education by her mother. Grandval’s father was a gifted pianist, but he was not a professional. In fact, like other musicians represented here, Grandval came from a wealthy or noble family; her father was an officer of the Légion d’honneur, and she was raised in a context where the intellectual life was highly prized, and members of the cultural elite were commonly invited to her family’s home. The same applies to Augusta Holmès, an Irish-born musician whose godfather was the famed author Alfred de Vigny; her own daughters would later be immortalized in a famous triple portrait by Auguste Renoir. Bertin’s father was active in the field of cultural journalism; Farrenc was the daughter of sculptor Jacques-Edme Dumont and the sister of another artist, Auguste. The only outsider, under this aspect, is Mel Bonis, who began her musical studies as a self-taught pianist at 12, thus demonstrating her exceptional talent. The relative homogeneity of the others’ family backgrounds is not casual, indeed, and can be found among the families of many other great female composers. In the past, women were less free than they are today to choose their own path in life; and, particularly if a lady wished to become a musician, she normally had to come either from a musicians’ family – where her talent would be discovered and appreciated – or from a wealthy background, where music would be a normal part of her education. Otherwise, there was little chance for her gift to come to light and be properly nourished.

Another trait which is shared by several of the musicians represented here, in fact, is their problematic relationship with the Conservatoire of Paris, which was – as still remains – the most important institution for musical education in France, and where all of them would have been fully qualified for pursuing their musical studies.

Boulanger studied privately harmony with Gabriel Fauré, counterpoint and fugue with Georges Caussade and composition with her sister Nadia. In her case, however, she was taught at home due to her very fragile health, and not for gender prejudices; in fact, she was later admitted to the Conservatoire (in 1909), where she completed her compositional studies with Paul Vidal.

Chaminade, auditioned by Félix Le Couppey at age 10, was encouraged by him to enroll at the Conservatoire, but her father was fiercely against this possibility, only allowing her to receive private tutoring by Le Couppey himself, by violinist Martin Pierre Marsick and by composers Marie-Gabriel-Augustin Savard and Benjamin Godard.

Bonis was supported by César Franck, who taught her piano and organ, and was admitted – exceptionally without an audition – to the Conservatoire upon a recommendation of the Director, Ambroise Thomas. Her teachers included Ernest Guiraud (who taught also Debussy), Albert Lavignac, Antoine Marmontel, and Jules Massenet.

As concerns Farrenc, she studied with Conservatory professors (including Anton Reicha), but it has not been ascertained whether she was actually a student at that institution, since at her time the composition class was not open to female students.

Bertin was a pupil of another major figure of her time’s France, i.e. François-Joseph Fétis; she shared with Boulanger the misfortune of having a serious health issue (she was partially paralyzed). Augusta Holmès could not attend the Conservatoire in spite of her obvious talent, and she studied privately with several teachers; the most important of them (both for his genius and for his influence on Holmès) was César Franck. Grandval studied composition with Friedrich Flotow and for a time with Frédéric Chopin; later, she was for two years a student of Camille Saint-Saëns, who dedicated one of his major sacred works to her.

In Grandval’s case, the responsibilities due to her social standing discouraged her from publishing her works under her real name, and therefore she adopted several pen names (Caroline Blangy, Clémence Valgrand, Maria Felicita de Reiset et Maria Reiset de Tesier, showing a penchant for wordplays and anagrams). Other musicians represented in this recording, instead, adopted pseudonyms for other reasons, primarily for the desire to be considered as “musicians” and “composers” rather than as “female” musicians or composers. For this reason, Augusta Holmès published her first works as Hermann Zenta, a distinctly male name. Mel Bonis, in turn, chose this abbreviated form of her first name, Mélanie, since “Mel” can be also a male name. And it is meaningful that Ambroise Thomas said of Cécile Chaminade: “This is not a woman who composes, but a composer who is a woman”, whilst Saint-Saëns said of Mel Bonis that he would not have imagined that a woman could compose that well.

The fates of these musicians were very different, instead: some enjoyed widespread acclaim during their lifetimes, others struggled to obtain recognition, others were rediscovered (long) after their death.

For instance, Grandval – also thanks to her social position – was a pre-eminent figure in the musical France of her time; she was awarded the Prix Rossini in 1881, and her works were often played at the Société Nationale de Musique (as were Chaminade’s). Holmès was commissioned a Triumphal Ode for the Exposition Universelle of 1889, and the size of the performing forces (some 1,200 people involved!) bears witness to the prestige of its composer. Louise Farrenc was an esteemed professor at the Conservatoire of Paris, and her Nonet was premiered by Joachim; she was twice awarded the Prix Chartier of the Académie des Beaux-Arts and her fame outlived her for years. Chaminade was honoured by the Académie Française and by Queen Victoria, and she was the first female composer to be awarded the National Order of the Légion d’Honneur. Lili Boulanger was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome at barely 20, the first female composer to win it. On the other hand, other composers were not so fortunate; Bertin’s last opera was ferociously thrashed by critics, and Mel Bonis’ outlived her own fame, before being rediscovered recently.

Together, these musicians bear witness to the fecundity of the female genius in the field of composition, and to how indeed the flute’s timbre seems to inspire female creativity. Their works, recorded here, in spite of their pronounced differences and marked distinctiveness, are all living testimonies to their composers’ genius, sensitivity, musical intelligence, and depth of inspiration and thought.

01. D'un matin de printemps

02. Sérénade aux étoiles, Op. 142

03. Air vaudois, Op. 108

04. Venez dans la prairie. 3ème Rondoletto sur la chansonnette de Dolive

05. Variations concertantes sur la tyrolienne de Me Gail, Op. 22: Celui qui sut toucher mon coeur

06. Le Loup-garou (Opéra comique en 1 acte)

07. Trois petites pièces: No. 1, Chanson

08. Trois petites pièces: No. 2, Clair de lune

09. Trois petites pièces: No. 3, Gigue

10. Suite pour flûte et piano: No. 1, Prélude

11. Suite pour flûte et piano: No. 2, Scherzo

12. Suite pour flûte et piano: No. 3, Menuet

13. Suite pour flûte et piano: No. 4, Romance

14. Suite pour flûte et piano: No. 5, Final

Among the many curiosities of classical music, several of which are rooted in, and justified by, the history of music, there is the “gendered” nature of some musical instruments. Most instruments are played today, and/or were played in the past, indifferently by men and women (although the actual possibilities of becoming professional players of that instrument were obviously different for men and women). Others are, or were, typically played by males or females, with a few instruments undergoing a “shift” in gender connotations through the ages. For an example of an instrument which was traditionally played by men only, and that even today is played overwhelmingly by men, the tuba is typical. In this case, there are also objective reasons for such a phenomenon, since the tuba is heavy to carry, and requires extra powerful lungs to be played; generally, therefore, the physical conformation of men makes them more “fit” to play such a physically demanding instrument. In other cases, an instrument was played in the past by both men and women, but today is more typically played by ladies – the harp is paradigmatic under this viewpoint. In the nineteenth century, for another example, amateur piano players were mostly female, although professional concert players were gentlemen or ladies indifferently. In still other cases, there are no physical reasons for a particular preference; rather, the higher percentage of male or female players for a specific instrument is due more to aesthetical reasons. A certain instrument is seen as more apt to symbolize the qualities traditionally associated with femininity or masculinity. And this is not without effects in the creation of new repertoire; there is in fact a hermeneutical circle by virtue of which the alleged gendered qualities of an instrument tend to be expressed in the music for that instrument, thus causing in turn a particular affinity between male or female players and that repertoire.

The flute, which is the coprotagonist – along with the piano – of this Da Vinci Classics album, is an instrument which is considered as having a certain “femininity”; although, obviously, there are excellent flutists of both sexes, this instrument still seems to attract a special attention from ladies, and so it was in the past. This album encompasses works for flute and piano written by female composers who lived in France between nineteenth and twentieth century. Their biographies, although very different under some aspects, have however some points in common which will be presently pointed out.

As concerns their birth dates, Louise Farrenc was born in 1804; Louise-Angélique Bertin in 1805; Clémence de Grandval in 1828; Augusta Holmès in 1847; Cécile Chaminade in 1857; Mel Bonis in 1858; and Lili Boulanger in 1893, thus encompassing the entire nineteenth century. Chaminade died at 86, in 1944; Grandval and Bonis both died at age 79; Bertin at 72; Farrenc at 71; Holmès at 56; whilst the youngest of this selection, Lili Boulanger, died at barely 25, outlived by a quarter of century by Chaminade; however, in spite of her extremely short life, Boulanger left a deep mark in the history of music.

As concerns their families, several of them came from musicians’ families. Boulanger was the sister of another very famed female musician, Nadia; their parents were a composer (Ernest, who won the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1835) and a Russian singer. Chaminade also came from a musical family, receiving her first piano education by her mother. Grandval’s father was a gifted pianist, but he was not a professional. In fact, like other musicians represented here, Grandval came from a wealthy or noble family; her father was an officer of the Légion d’honneur, and she was raised in a context where the intellectual life was highly prized, and members of the cultural elite were commonly invited to her family’s home. The same applies to Augusta Holmès, an Irish-born musician whose godfather was the famed author Alfred de Vigny; her own daughters would later be immortalized in a famous triple portrait by Auguste Renoir. Bertin’s father was active in the field of cultural journalism; Farrenc was the daughter of sculptor Jacques-Edme Dumont and the sister of another artist, Auguste. The only outsider, under this aspect, is Mel Bonis, who began her musical studies as a self-taught pianist at 12, thus demonstrating her exceptional talent. The relative homogeneity of the others’ family backgrounds is not casual, indeed, and can be found among the families of many other great female composers. In the past, women were less free than they are today to choose their own path in life; and, particularly if a lady wished to become a musician, she normally had to come either from a musicians’ family – where her talent would be discovered and appreciated – or from a wealthy background, where music would be a normal part of her education. Otherwise, there was little chance for her gift to come to light and be properly nourished.

Another trait which is shared by several of the musicians represented here, in fact, is their problematic relationship with the Conservatoire of Paris, which was – as still remains – the most important institution for musical education in France, and where all of them would have been fully qualified for pursuing their musical studies.

Boulanger studied privately harmony with Gabriel Fauré, counterpoint and fugue with Georges Caussade and composition with her sister Nadia. In her case, however, she was taught at home due to her very fragile health, and not for gender prejudices; in fact, she was later admitted to the Conservatoire (in 1909), where she completed her compositional studies with Paul Vidal.

Chaminade, auditioned by Félix Le Couppey at age 10, was encouraged by him to enroll at the Conservatoire, but her father was fiercely against this possibility, only allowing her to receive private tutoring by Le Couppey himself, by violinist Martin Pierre Marsick and by composers Marie-Gabriel-Augustin Savard and Benjamin Godard.

Bonis was supported by César Franck, who taught her piano and organ, and was admitted – exceptionally without an audition – to the Conservatoire upon a recommendation of the Director, Ambroise Thomas. Her teachers included Ernest Guiraud (who taught also Debussy), Albert Lavignac, Antoine Marmontel, and Jules Massenet.

As concerns Farrenc, she studied with Conservatory professors (including Anton Reicha), but it has not been ascertained whether she was actually a student at that institution, since at her time the composition class was not open to female students.

Bertin was a pupil of another major figure of her time’s France, i.e. François-Joseph Fétis; she shared with Boulanger the misfortune of having a serious health issue (she was partially paralyzed). Augusta Holmès could not attend the Conservatoire in spite of her obvious talent, and she studied privately with several teachers; the most important of them (both for his genius and for his influence on Holmès) was César Franck. Grandval studied composition with Friedrich Flotow and for a time with Frédéric Chopin; later, she was for two years a student of Camille Saint-Saëns, who dedicated one of his major sacred works to her.

In Grandval’s case, the responsibilities due to her social standing discouraged her from publishing her works under her real name, and therefore she adopted several pen names (Caroline Blangy, Clémence Valgrand, Maria Felicita de Reiset et Maria Reiset de Tesier, showing a penchant for wordplays and anagrams). Other musicians represented in this recording, instead, adopted pseudonyms for other reasons, primarily for the desire to be considered as “musicians” and “composers” rather than as “female” musicians or composers. For this reason, Augusta Holmès published her first works as Hermann Zenta, a distinctly male name. Mel Bonis, in turn, chose this abbreviated form of her first name, Mélanie, since “Mel” can be also a male name. And it is meaningful that Ambroise Thomas said of Cécile Chaminade: “This is not a woman who composes, but a composer who is a woman”, whilst Saint-Saëns said of Mel Bonis that he would not have imagined that a woman could compose that well.

The fates of these musicians were very different, instead: some enjoyed widespread acclaim during their lifetimes, others struggled to obtain recognition, others were rediscovered (long) after their death.

For instance, Grandval – also thanks to her social position – was a pre-eminent figure in the musical France of her time; she was awarded the Prix Rossini in 1881, and her works were often played at the Société Nationale de Musique (as were Chaminade’s). Holmès was commissioned a Triumphal Ode for the Exposition Universelle of 1889, and the size of the performing forces (some 1,200 people involved!) bears witness to the prestige of its composer. Louise Farrenc was an esteemed professor at the Conservatoire of Paris, and her Nonet was premiered by Joachim; she was twice awarded the Prix Chartier of the Académie des Beaux-Arts and her fame outlived her for years. Chaminade was honoured by the Académie Française and by Queen Victoria, and she was the first female composer to be awarded the National Order of the Légion d’Honneur. Lili Boulanger was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome at barely 20, the first female composer to win it. On the other hand, other composers were not so fortunate; Bertin’s last opera was ferociously thrashed by critics, and Mel Bonis’ outlived her own fame, before being rediscovered recently.

Together, these musicians bear witness to the fecundity of the female genius in the field of composition, and to how indeed the flute’s timbre seems to inspire female creativity. Their works, recorded here, in spite of their pronounced differences and marked distinctiveness, are all living testimonies to their composers’ genius, sensitivity, musical intelligence, and depth of inspiration and thought.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads