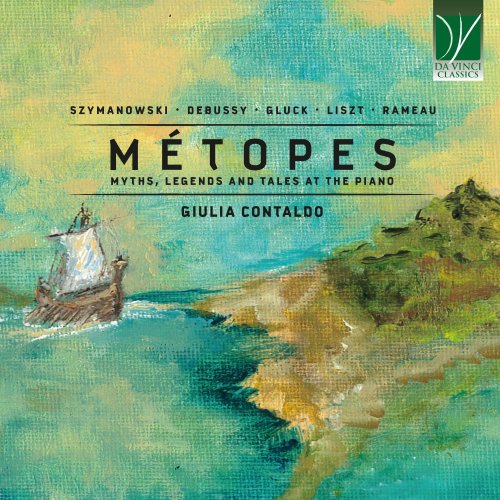

Giulia Contaldo - Métopes: Myths, Legends and Tales (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Giulia Contaldo

- Title: Métopes: Myths, Legends and Tales

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:10:24

- Total Size: 167 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Métopes 'Trois Poèmes', Op. 29: No. 1, L'île des Sirènes

02. Métopes 'Trois Poèmes', Op. 29: No. 2, Calypso

03. Métopes 'Trois Poèmes', Op. 29: No. 3, Nausicaa

04. Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, L. 86 (For Solo Piano)

05. Orfeo ed Euridice, Wq 30

06. from Two Légendes, I. Saint François d'Assise, S. 175

07. from Années de pèlerinage. Première Année, S. 160

08. Tristan und Isolde, S.447: No. 1, Isoldes Liebestod

09. Les Cyclopes (From Pièces de clavecin)

Myths have always been a source of inspiration, offering timeless stories that resonate across cultures and generations. This recording brings ancient tales into the present, using music to explore their emotional and symbolic depth.

In classical architecture, “metopes” are the spaces between the triglyphs in a Doric frieze, often adorned with sculptural depictions of mythological scenes. These spaces served as a canvas for stories and legends to come to life, much like how the works on this CD bring mythological tales into musical form. By naming the project “Metopes,” the title highlights how music, like the sculpted images of ancient metopes, immortalizes and transforms myths into a vivid, expressive art form. Each composition becomes a modern “metope,” preserving and reinterpreting legendary tales—from Orfeo and Euridice to the Sirens and the journey of Odysseus (Ulysses).

Through this project, mythology becomes a bridge between the past and the present, showing how its themes still resonate today. Mythology provides a narrative and message familiar to every man, creating a common foundation from which the artist can lead his public.

The album opens with what is perhaps the piano masterpiece of its composer, Karol Szymanowski. He wrote it in 1914, when he returned to his Ukrainian homeland after having toured extensively Europe. He had been particularly impressed by Italy, and especially by Sicily. The triangular-shaped island, the southernmost region in Italy, is the cradle of Italian culture. In it are found some of the finest examples of Greek art and culture, miraculously preserved through the centuries and in spite of the numerous invasions and earthquakes undergone by this beautiful island. Magna Graecia – so was Southern Italy known – was a hotbed of splendid culture and artistry, which still radiates its fascination to the other regions of Italy. It has been argued by musicologist Christoph Palmer that the ultimate inspiration for Szymanowski’s composition came from his visit to the Museum of Palermo, the capital city of Sicily, where some of the most exquisite surviving metopes are found. This is very likely to be the true source for Szymanowski’s work, although it has also to be said that he was looking with particular interest to the Classical world, its myths, and its tropes at that time.

In the same year of Métopes, Szymanowski had written a similarly titled work for violin and piano, i.e. Mythes op. 30. However, the liveliness of Mythes becomes something more transcendent and stylized, more transfigured and ethereal in his piano Métopes. The mythical episodes chosen by Szymanowski, in harmony with his sculptural models, are particularly well suited for this kind of treatment. In spite of a very thick harmonic texture, which makes use of the most modern harmonic language available at Szymanowski’s time, the result is in fact extremely “light”, frequently evoking liquid textures. This kind of approach is very demanding and requires a performer with exceptional skills. In L’île des Sirènes, the language is built on what is defined by Palmer as follows: “watery trills and tremolos; atmospheric use of the pedal to form a haze of sound; fine sprays of arpeggio; voluptuously spread chords; fine threads of melismata and arabesque on the one hand, sonorous climaxes on the other, all spun from the merest motivic fragments”.

Calypso evokes a number of different aspects and images. There is, once more, the idea of water and sea, since Calypso lives on an island; there is female beauty and fascination – a dangerous kind of seduction, in this case -; and there is nostalgia, quintessential to the character of Ulysses. Indeed, the hero’s failed attempts to escape the nymph’s bonds are suggestively depicted musically by Szymanowski, since there are several motifs which would have the potential for becoming themes but are seemingly blocked by “memories” of previously heard motifs. Furthermore, Calypso the nymph seems to suggest musical parallels with Ondine, another mythical figure related to water and memorably portrayed by Maurice Ravel.

Another female figure deeply connected with the sea is Nausicaa, although her character is highly positive in comparison with Calypso’s. Here she is seen in the full blossoming grace of her youth and innocence; she dances, and her beauty and suavity are a welcome respite, almost like an otherworldly vision, for the shipwrecked Ulysses. Surprisingly, however, Szymanowski suggests that Nausicaa and Calypso may have more in common than it seems: a thematic echo from Calypso’s music surfaces in Nausicaa’s, and a hint of seductiveness emerges in the purity of the adolescent princess, the daughter of the king of the Phaeacians.

Claude Debussy turns his attention in turn to the world of classical mythology, with a figure which is practically the contrary of Nausicaa’s. The demigod Pan, a Faun, is a demonic character; even in his physical appearance he is almost beastly, and he is frequently taken as a symbol for lust. In spite of this, Pan is an excellent musician: here too, therefore, there may be more in the myth than it seems at first, and somebody who is seemingly negative may have something beautiful to offer. Debussy’s music is rightly considered as one of his masterpieces. Written in 1894 and premiered by Georges Barrère, it is inspired by a poem by Mallarmé, by the title of L’après-midi d’un faune. In Debussy’s own words, “The music of this prelude is a very free illustration of Mallarmé’s beautiful poem. By no means does it claim to be a synthesis of it. Rather there is a succession of scenes through which pass the desires and dreams of the faun in the heat of the afternoon. Then, tired of pursuing the timorous flight of nymphs and naiads, he succumbs to intoxicating sleep, in which he can finally realize his dreams of possession in universal Nature”. The poet was at first very perplexed by the idea that his verses could inspire musical works, since he believed that the musicality of his poetry was sufficient in itself. However, he was deeply impressed by Debussy’s version, which surprised him deeply. He would write to the composer: “The marvel! Your illustration of the Afternoon of a Faun presents no dissonance with my text, but goes much further, really, into nostalgia and into light, with finesse, with sensuality, with richness”.

Probably, what convinced Mallarmé is that Debussy made no claim and no attempt to “describe” the poem in music, or to follow it in the form of a tone poem. Rather, the work is a succession of “impressions” (justifying, in this case, the epithet of Impressionist given to Debussy’s music at times too undiscriminatingly), which render in music those provoked by the reading of Mallarmé’s lines. In comparison with Mallarmé, the title of Debussy’s work adds the word Prélude: in fact, the composer had planned to write two other movements (an Interlude and Paraphrase), but in the end he preferred compactness and intensity to size.

The task of transcribing Debussy’s hyper-refined orchestration for performance on the piano is not easy, but the arrangement played here is a magnificent demonstration of how the piano can evoke an entire orchestral texture, seemingly effortlessly.

Another arrangement signed by one of the most important Italian composers of instrumental music in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century follows immediately. The extremely famous Melody excerpted from Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice is a beautiful demonstration of Sgambati’s skill as a pianist and as a composer for the piano. Orfeo ed Euridice left an important mark in the history of Western Opera (just as Monteverdi’s Orfeo had paved the way for it); in it, Gluck expressed his ideals of expressivity, sobriety, and connection between words and music, in such a fashion that later composers would ceaselessly return to the Olympian purity of his writing.

Three works by Franz Liszt are presented later; one is a transcription (after one of Wagner’s most beautiful scenes, describing the “love death” of Isolde), and the others are original works. The legend of St. Francis of Assisi preaching to the birds is certainly a very different kind of narrative from those hitherto mentioned. Here the protagonist is not a mythical figure, whose existence can be prudently discussed, but rather a historical character who is well documented; and although hagiography may at times inflate or expand what we would describe as “historical truth”, there are objective documents and foundations on which Francis’ experience may be described. Liszt, who was deeply religious and was also a Franciscan Tertiary, seems to be particularly inspired by the possibility of evoking birdsong.

La Vallée d’Obermann, from Années de pèlerinage (I – Suisse), is inspired by still another kind of story, i.e. that narrated by Senancour and set to poetical verse by Byron. Literature, rather than direct observation of nature, is the main source for Liszt’s solo piano work, a majestic and powerfully expressive evocation of the natural and supernatural forces at work in the visible world. Liszt here seems to write a piano transcription of an imaginary orchestral work, since many of his indication suggest timbres from a symphonic orchestra.

Finally, there is a work from the French Baroque era, where the grotesque, the sublime, and the mythical were all sides of the same coin, that of surprise and wonder. Rameau chose to describe the disquieting and monstruous form of the Cyclopes through his music. Their gigantic stature and Polyphemus’ single eye make them exceptional, and so is his music; furthermore, the Cyclopes are blacksmiths, and the innovative technique created by Rameau for playing repeated notes seems to be a perfect tool for reproducing the clashing noises of their workshop.

Together, the works in this album demonstrate the fecundity of mythological literature as a source of inspiration, and how it can provide material both for the most elegant and exquisite forms of musicianship, and for those which are more related with horror and monstrosity. Both, in fact, are aspects of the human beings’ experience, and such they have been narrated in words and re-narrated in music.

01. Métopes 'Trois Poèmes', Op. 29: No. 1, L'île des Sirènes

02. Métopes 'Trois Poèmes', Op. 29: No. 2, Calypso

03. Métopes 'Trois Poèmes', Op. 29: No. 3, Nausicaa

04. Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, L. 86 (For Solo Piano)

05. Orfeo ed Euridice, Wq 30

06. from Two Légendes, I. Saint François d'Assise, S. 175

07. from Années de pèlerinage. Première Année, S. 160

08. Tristan und Isolde, S.447: No. 1, Isoldes Liebestod

09. Les Cyclopes (From Pièces de clavecin)

Myths have always been a source of inspiration, offering timeless stories that resonate across cultures and generations. This recording brings ancient tales into the present, using music to explore their emotional and symbolic depth.

In classical architecture, “metopes” are the spaces between the triglyphs in a Doric frieze, often adorned with sculptural depictions of mythological scenes. These spaces served as a canvas for stories and legends to come to life, much like how the works on this CD bring mythological tales into musical form. By naming the project “Metopes,” the title highlights how music, like the sculpted images of ancient metopes, immortalizes and transforms myths into a vivid, expressive art form. Each composition becomes a modern “metope,” preserving and reinterpreting legendary tales—from Orfeo and Euridice to the Sirens and the journey of Odysseus (Ulysses).

Through this project, mythology becomes a bridge between the past and the present, showing how its themes still resonate today. Mythology provides a narrative and message familiar to every man, creating a common foundation from which the artist can lead his public.

The album opens with what is perhaps the piano masterpiece of its composer, Karol Szymanowski. He wrote it in 1914, when he returned to his Ukrainian homeland after having toured extensively Europe. He had been particularly impressed by Italy, and especially by Sicily. The triangular-shaped island, the southernmost region in Italy, is the cradle of Italian culture. In it are found some of the finest examples of Greek art and culture, miraculously preserved through the centuries and in spite of the numerous invasions and earthquakes undergone by this beautiful island. Magna Graecia – so was Southern Italy known – was a hotbed of splendid culture and artistry, which still radiates its fascination to the other regions of Italy. It has been argued by musicologist Christoph Palmer that the ultimate inspiration for Szymanowski’s composition came from his visit to the Museum of Palermo, the capital city of Sicily, where some of the most exquisite surviving metopes are found. This is very likely to be the true source for Szymanowski’s work, although it has also to be said that he was looking with particular interest to the Classical world, its myths, and its tropes at that time.

In the same year of Métopes, Szymanowski had written a similarly titled work for violin and piano, i.e. Mythes op. 30. However, the liveliness of Mythes becomes something more transcendent and stylized, more transfigured and ethereal in his piano Métopes. The mythical episodes chosen by Szymanowski, in harmony with his sculptural models, are particularly well suited for this kind of treatment. In spite of a very thick harmonic texture, which makes use of the most modern harmonic language available at Szymanowski’s time, the result is in fact extremely “light”, frequently evoking liquid textures. This kind of approach is very demanding and requires a performer with exceptional skills. In L’île des Sirènes, the language is built on what is defined by Palmer as follows: “watery trills and tremolos; atmospheric use of the pedal to form a haze of sound; fine sprays of arpeggio; voluptuously spread chords; fine threads of melismata and arabesque on the one hand, sonorous climaxes on the other, all spun from the merest motivic fragments”.

Calypso evokes a number of different aspects and images. There is, once more, the idea of water and sea, since Calypso lives on an island; there is female beauty and fascination – a dangerous kind of seduction, in this case -; and there is nostalgia, quintessential to the character of Ulysses. Indeed, the hero’s failed attempts to escape the nymph’s bonds are suggestively depicted musically by Szymanowski, since there are several motifs which would have the potential for becoming themes but are seemingly blocked by “memories” of previously heard motifs. Furthermore, Calypso the nymph seems to suggest musical parallels with Ondine, another mythical figure related to water and memorably portrayed by Maurice Ravel.

Another female figure deeply connected with the sea is Nausicaa, although her character is highly positive in comparison with Calypso’s. Here she is seen in the full blossoming grace of her youth and innocence; she dances, and her beauty and suavity are a welcome respite, almost like an otherworldly vision, for the shipwrecked Ulysses. Surprisingly, however, Szymanowski suggests that Nausicaa and Calypso may have more in common than it seems: a thematic echo from Calypso’s music surfaces in Nausicaa’s, and a hint of seductiveness emerges in the purity of the adolescent princess, the daughter of the king of the Phaeacians.

Claude Debussy turns his attention in turn to the world of classical mythology, with a figure which is practically the contrary of Nausicaa’s. The demigod Pan, a Faun, is a demonic character; even in his physical appearance he is almost beastly, and he is frequently taken as a symbol for lust. In spite of this, Pan is an excellent musician: here too, therefore, there may be more in the myth than it seems at first, and somebody who is seemingly negative may have something beautiful to offer. Debussy’s music is rightly considered as one of his masterpieces. Written in 1894 and premiered by Georges Barrère, it is inspired by a poem by Mallarmé, by the title of L’après-midi d’un faune. In Debussy’s own words, “The music of this prelude is a very free illustration of Mallarmé’s beautiful poem. By no means does it claim to be a synthesis of it. Rather there is a succession of scenes through which pass the desires and dreams of the faun in the heat of the afternoon. Then, tired of pursuing the timorous flight of nymphs and naiads, he succumbs to intoxicating sleep, in which he can finally realize his dreams of possession in universal Nature”. The poet was at first very perplexed by the idea that his verses could inspire musical works, since he believed that the musicality of his poetry was sufficient in itself. However, he was deeply impressed by Debussy’s version, which surprised him deeply. He would write to the composer: “The marvel! Your illustration of the Afternoon of a Faun presents no dissonance with my text, but goes much further, really, into nostalgia and into light, with finesse, with sensuality, with richness”.

Probably, what convinced Mallarmé is that Debussy made no claim and no attempt to “describe” the poem in music, or to follow it in the form of a tone poem. Rather, the work is a succession of “impressions” (justifying, in this case, the epithet of Impressionist given to Debussy’s music at times too undiscriminatingly), which render in music those provoked by the reading of Mallarmé’s lines. In comparison with Mallarmé, the title of Debussy’s work adds the word Prélude: in fact, the composer had planned to write two other movements (an Interlude and Paraphrase), but in the end he preferred compactness and intensity to size.

The task of transcribing Debussy’s hyper-refined orchestration for performance on the piano is not easy, but the arrangement played here is a magnificent demonstration of how the piano can evoke an entire orchestral texture, seemingly effortlessly.

Another arrangement signed by one of the most important Italian composers of instrumental music in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century follows immediately. The extremely famous Melody excerpted from Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice is a beautiful demonstration of Sgambati’s skill as a pianist and as a composer for the piano. Orfeo ed Euridice left an important mark in the history of Western Opera (just as Monteverdi’s Orfeo had paved the way for it); in it, Gluck expressed his ideals of expressivity, sobriety, and connection between words and music, in such a fashion that later composers would ceaselessly return to the Olympian purity of his writing.

Three works by Franz Liszt are presented later; one is a transcription (after one of Wagner’s most beautiful scenes, describing the “love death” of Isolde), and the others are original works. The legend of St. Francis of Assisi preaching to the birds is certainly a very different kind of narrative from those hitherto mentioned. Here the protagonist is not a mythical figure, whose existence can be prudently discussed, but rather a historical character who is well documented; and although hagiography may at times inflate or expand what we would describe as “historical truth”, there are objective documents and foundations on which Francis’ experience may be described. Liszt, who was deeply religious and was also a Franciscan Tertiary, seems to be particularly inspired by the possibility of evoking birdsong.

La Vallée d’Obermann, from Années de pèlerinage (I – Suisse), is inspired by still another kind of story, i.e. that narrated by Senancour and set to poetical verse by Byron. Literature, rather than direct observation of nature, is the main source for Liszt’s solo piano work, a majestic and powerfully expressive evocation of the natural and supernatural forces at work in the visible world. Liszt here seems to write a piano transcription of an imaginary orchestral work, since many of his indication suggest timbres from a symphonic orchestra.

Finally, there is a work from the French Baroque era, where the grotesque, the sublime, and the mythical were all sides of the same coin, that of surprise and wonder. Rameau chose to describe the disquieting and monstruous form of the Cyclopes through his music. Their gigantic stature and Polyphemus’ single eye make them exceptional, and so is his music; furthermore, the Cyclopes are blacksmiths, and the innovative technique created by Rameau for playing repeated notes seems to be a perfect tool for reproducing the clashing noises of their workshop.

Together, the works in this album demonstrate the fecundity of mythological literature as a source of inspiration, and how it can provide material both for the most elegant and exquisite forms of musicianship, and for those which are more related with horror and monstrosity. Both, in fact, are aspects of the human beings’ experience, and such they have been narrated in words and re-narrated in music.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads