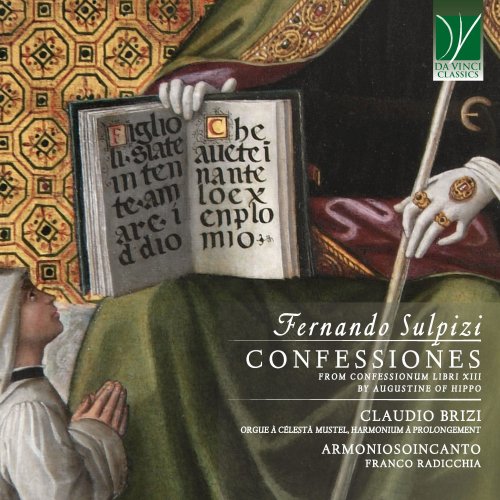

Claudio Brizi, Armoniosoincanto, Giulio Giurati, Franco Radicchia - Fernando Sulpizi: Confessiones, An excerpts from Confessionum libri XIII by Augustine of Hippo (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Claudio Brizi, Armoniosoincanto, Giulio Giurati, Franco Radicchia

- Title: Fernando Sulpizi: Confessiones, An excerpts from Confessionum libri XIII by Augustine of Hippo

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:05:34

- Total Size: 294 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Libro, vol. III: No. 1, Simpliciano servo di Dio

02. Libro, vol. III: No. 2, Il legame della donna

03. Libro, vol. III: No. 3, Conversione di Vittorino nel ricordo di Simpliciano

04. Libro, vol. III: No. 4, Vittorino diceva a Simpliciano

05. Libro, vol. III: No. 5, La conversione di Vittorino

06. Libro, vol. III: No. 6, L’esultanza per il bene faticosamente raggiunto

07. Libro, vol. III: No. 7, Quid agitur in anima?

08. Libro, Vol. III: No. 10, Amemus! Curramus!

09. Libro, Vol. III: No. 11, Ipsa veritas certa est

10. Libro, Vol. III: No. 12, Sarcina saeculi

11. Libro, vol. III: No. 13, Agostino, Alipio, Nebridio

12. Libro, vol. III: No. 14, Un’avventura di Ponticiano e tre suoi amici

13. Libro, vol. III: No. 15, Un’avventura di Ponticiano (Seconda parte)

14. Libro, vol. III: No. 16, Miseria e pena di Agostino

15. Libro, Vol. III: No. 17, Non plene volebam nec plene nolebam

16. Libro, Vol. III: No. 18, Ita rodebar intus

17. Libro, Vol. III: No. 20, Ipsum velle iam facere erat

18. Libro, Vol. III: No. 21, Unde hoc monstrum

19. Libro, vol. III: No. 22, Scompaiano dalla tua vista, o Dio

20. Libro, Vol. III: No. 23, Ecce due naturae

21. Libro, Vol. III: No. 24, Iam ergo non dicant

22. Libro, vol. III: No. 25, Penosa ascesa

23. Libro, vol. III: No. 28, La conversione

24. Libro I

25. Libro II

26. Libro III

27. Libro IV

28. Libro V

29. Libro, vol. I

30. Libro, vol. II

31. Libro IX

32. Libro X

33. Libro XI

34. Libro XII

35. Libro XIII

Can music be a pathway to God? Or at least to transcendence and spirituality? Most people throughout history – at least those who believe in God, or in transcendence, or in spirituality – would be inclined to answer in the affirmative. There is a hidden, but very much real, thread, which unites the spiritual experience of human beings with their musicality. It is as if the sphere of transcendence and that of musicianship would share at least a part of their spaces.

To investigate if, how, and why this happens is the task of the theology of music. It is a relatively young discipline, at least in the academic sense (there are just a few chairs in the theology of music at universities worldwide). However, in its true essence, it is one of the oldest disciplines in music history.

The connection between music and the sacred belongs in the human experience of virtually all peoples, regardless of their degree of “civilization”. Music has always been a vital part of worship, in all of its forms. And, as soon as some kind of theology was developed by a society, it was very common for a musical element to be included. There are many creation myths which involve “singing the world into being” or other “en-chant-ments”. The Greek culture knows several music-making gods and goddesses (from Apollo to the Muses, but there are many more than these), and Greek philosophy has wonderfully developed the role of music in the cosmos, in the human psyche, in society, and in the religious experience which embraces these all.

The Bible is replete with music, from the first musicians (who were the “grandchildren” of Adam and Eve, according to the Book of Genesis) to the wonderful vision of the Heavenly Jerusalem which is almost an eternal concert. At the Bible’s heart is the Psalter, or Book of Psalms, which are beautiful compositions, destined for singing, and commonly sung by both Jews and Christians.

However, for a “theology of music” proper we have to await the Church Fathers. Many Greek Fathers (Clement of Alexandria is first and foremost) have employed musical analogies or metaphors to convey something of the mystery of God, at times with exceptionally profound results. But the laurel for the deepest and most thorough theologian of music in the first millennium (possibly he deserves that laurel without any temporal qualification) goes certainly to Augustine of Hippo, venerated as a saint and a Doctor of the Church by Catholics.

Augustine’s life is one of the most fascinating in the history of Christianity. And we know it in great detail, because he told it himself, in one of the foundational books of Western thought, the Confessions. Augustine had always displayed exceptional intellectual gifts, ascending the social ladder very quickly and becoming a very appreciated figure in the society of his time. With fame and success, however, other less desirable qualities had also befallen him: pride, vanity, self-conceit. Furthermore, this brilliant man was undeniably fascinating in the female eyes. He was more or less faithful to a particular woman, who gave him a very beloved son, but there were also other ladies in his life.

He was interested in things religious, but he had been captured by a heretical movement called Manicheism, according to which there was not the One God, but rather two godheads, one good and benevolent, the other evil and malevolent.

One turning point in Augustine’s life came with his encounter with St. Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan, whose intellectual stance could match Augustine’s (it is difficult to find worthy interlocutors when you are an absolute genius…) and whose holiness deeply impressed him. Furthermore (and perhaps even more importantly), Augustine’s mother, Monica, was intensely Catholic, and she had shed countless tears over her son’s dissolute way of living – belonging in a heretical sect, being proud, and having several adventures with the gentle sex.

Her prayers were heard (and for this reason she has earned the role of patron saint of parents who are anguished for their children). Augustine felt the “shock of Grace” and converted to Catholicism, later to be ordained a bishop and to become one of the greatest figures of Christianity.

The experience of conversion is told by Augustine in the Confessions, one of his masterpieces where he narrates, without filters and without shame, what he was and how God led him to become what he would become. And it is told in fascinatingly sensory terms: “Late have I loved you, beauty so old and so new: late have I loved you. […] You called and cried out loud and shattered my deafness. You were radiant and resplendent, you put to flight my blindness. You were fragrant, and I drew in my breath and now pant after you. I tasted you, and I feel but hunger and thirst for you. You touched me, and I am set on fire to attain the peace which is yours”.

In fact, music had not been indifferent to Augustine’s experience of God and of faith. Already before converting, he had authored a fundamental treatise called De musica, in which he discusses mainly the rules of prosody. Later, he left memorable pages about the role of music in the faithful’s itinerary toward the “City of God”, as he called it.

Augustine certainly felt the power of music to draw the souls to transcendence; however, he was one of the few who was also alert to the “dangers” of music. The art of sounds captivates its listeners, but it may either lead them to God, or lead them astray, distract them. Augustine knew all this because he had experienced this. “Now, in those airs which Your words breathe soul into, when sung with a sweet and trained voice, do I somewhat repose; yet not so as to cling to them, but so as to free myself when I wish. […] I perceive that our minds are more devoutly and earnestly elevated into a flame of piety by the holy words themselves when they are thus sung, than when they are not. […] When I call to mind the tears I shed at the songs of Your Church, at the outset of my recovered faith, and how even now I am moved not by the singing but by what is sung, when they are sung with a clear and skilfully modulated voice, I then acknowledge the great utility of this custom. […] Yet when it happens to me to be more moved by the singing than by what is sung, I confess myself to have sinned criminally, and then I would rather not have heard the singing”.

This passage is rather typical for Augustine’s deep soul-searching, for his capability to delve deeply into the motivations and motives of the soul’s affections, and also for the contradictions inherent in the human mind, soul, and experience, which he outlines very clearly.

In spite of his perplexities, still, undeniably Augustine was fascinated by music. Indeed, he theorized wordless singing (the jubilatio or jubilus) as the highpoint of mystical exultation in God, and thus he paved the way for instrumental music in church.

It is therefore particularly fitting that his Confessions receive a musical frame with the masterly work of Fr Sulpizi recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album. Fr Sulpizi explains the reasons behind his undertaking – to write thirteen musical pieces to accompany the Confessions. In his words, “My goal was to enhance the experience of the text through an actor’s interpretation and to create reflective spaces by interspersing the reading of the chapters with music. By closing one’s eyes, listening to the words, and savoring their meaning as the notes flow, I hope to share the emotions evoked in me by the text and the music”.

In Fr Sulpizi’s work, an actor performs Augustine’s words, instead of the more usual silent act of private reading. This adds “something unique through the sound of the voice, which flows, vibrates, and intertwines with the sounds of the instruments”.

Fr Sulpizi considers Augustine’s reading of a Gospel episode, when John the Baptist identified himself as “the voice of one crying in the wilderness”. This passage has been commented upon by Augustine himself, noting that John is referred to as the “voice,” while the Lord is called the “Word,” as in “In the beginning was the Word”. “John, as the voice, exists only for a time, while Christ, as the Word, is eternal. The voice, a sound, becomes a word and conveys thought. While the sound fades away, the thought communicated by the word lingers in the listener’s soul. This concept underpins my effort to complete this work”. In fact, as Fr Sulpizi explains, “hearing the text through an interpreter allows for a richer appreciation of Augustine’s life story—so full of suffering, restlessness, and yearning for truth, ultimately fulfilled in the contemplation of creation”.

Furthermore, another aspect of Augustine’s thought which has deeply influenced Fr Sulpizi’s musical concept (“since 1975”, as he specifies), is what he calls the “characteristic musical idea.” This theory, inspired by Augustine’s reflections on time, identifies three faculties that enable us to understand time and existence within it: “expectation, which makes the future present; attention, which renders the present accessible; and memory, which makes the past present. Music, being inextricably linked to time, can be described as an event that colors time. To be perceived and appreciated, it must first be anticipated (awaited to reach the ear), then attentively listened to (to be internalized), and finally entrusted to memory. Without the mysterious preservation of memory, music fades, dissipates, appearing and disappearing almost into nothingness”. In this fashion, memory becomes crucial for preserving and recognizing the unique qualities of a musical idea, allowing it to be identified as a unified structure. Thus comes to light this touching, profound, deep, and fascinating composition, in which the reading of the thirteen books of the Confessions is framed by a corresponding number of musical items; different instrumental arrangements are employed, with each book concluding with a chorus of female voices.

01. Libro, vol. III: No. 1, Simpliciano servo di Dio

02. Libro, vol. III: No. 2, Il legame della donna

03. Libro, vol. III: No. 3, Conversione di Vittorino nel ricordo di Simpliciano

04. Libro, vol. III: No. 4, Vittorino diceva a Simpliciano

05. Libro, vol. III: No. 5, La conversione di Vittorino

06. Libro, vol. III: No. 6, L’esultanza per il bene faticosamente raggiunto

07. Libro, vol. III: No. 7, Quid agitur in anima?

08. Libro, Vol. III: No. 10, Amemus! Curramus!

09. Libro, Vol. III: No. 11, Ipsa veritas certa est

10. Libro, Vol. III: No. 12, Sarcina saeculi

11. Libro, vol. III: No. 13, Agostino, Alipio, Nebridio

12. Libro, vol. III: No. 14, Un’avventura di Ponticiano e tre suoi amici

13. Libro, vol. III: No. 15, Un’avventura di Ponticiano (Seconda parte)

14. Libro, vol. III: No. 16, Miseria e pena di Agostino

15. Libro, Vol. III: No. 17, Non plene volebam nec plene nolebam

16. Libro, Vol. III: No. 18, Ita rodebar intus

17. Libro, Vol. III: No. 20, Ipsum velle iam facere erat

18. Libro, Vol. III: No. 21, Unde hoc monstrum

19. Libro, vol. III: No. 22, Scompaiano dalla tua vista, o Dio

20. Libro, Vol. III: No. 23, Ecce due naturae

21. Libro, Vol. III: No. 24, Iam ergo non dicant

22. Libro, vol. III: No. 25, Penosa ascesa

23. Libro, vol. III: No. 28, La conversione

24. Libro I

25. Libro II

26. Libro III

27. Libro IV

28. Libro V

29. Libro, vol. I

30. Libro, vol. II

31. Libro IX

32. Libro X

33. Libro XI

34. Libro XII

35. Libro XIII

Can music be a pathway to God? Or at least to transcendence and spirituality? Most people throughout history – at least those who believe in God, or in transcendence, or in spirituality – would be inclined to answer in the affirmative. There is a hidden, but very much real, thread, which unites the spiritual experience of human beings with their musicality. It is as if the sphere of transcendence and that of musicianship would share at least a part of their spaces.

To investigate if, how, and why this happens is the task of the theology of music. It is a relatively young discipline, at least in the academic sense (there are just a few chairs in the theology of music at universities worldwide). However, in its true essence, it is one of the oldest disciplines in music history.

The connection between music and the sacred belongs in the human experience of virtually all peoples, regardless of their degree of “civilization”. Music has always been a vital part of worship, in all of its forms. And, as soon as some kind of theology was developed by a society, it was very common for a musical element to be included. There are many creation myths which involve “singing the world into being” or other “en-chant-ments”. The Greek culture knows several music-making gods and goddesses (from Apollo to the Muses, but there are many more than these), and Greek philosophy has wonderfully developed the role of music in the cosmos, in the human psyche, in society, and in the religious experience which embraces these all.

The Bible is replete with music, from the first musicians (who were the “grandchildren” of Adam and Eve, according to the Book of Genesis) to the wonderful vision of the Heavenly Jerusalem which is almost an eternal concert. At the Bible’s heart is the Psalter, or Book of Psalms, which are beautiful compositions, destined for singing, and commonly sung by both Jews and Christians.

However, for a “theology of music” proper we have to await the Church Fathers. Many Greek Fathers (Clement of Alexandria is first and foremost) have employed musical analogies or metaphors to convey something of the mystery of God, at times with exceptionally profound results. But the laurel for the deepest and most thorough theologian of music in the first millennium (possibly he deserves that laurel without any temporal qualification) goes certainly to Augustine of Hippo, venerated as a saint and a Doctor of the Church by Catholics.

Augustine’s life is one of the most fascinating in the history of Christianity. And we know it in great detail, because he told it himself, in one of the foundational books of Western thought, the Confessions. Augustine had always displayed exceptional intellectual gifts, ascending the social ladder very quickly and becoming a very appreciated figure in the society of his time. With fame and success, however, other less desirable qualities had also befallen him: pride, vanity, self-conceit. Furthermore, this brilliant man was undeniably fascinating in the female eyes. He was more or less faithful to a particular woman, who gave him a very beloved son, but there were also other ladies in his life.

He was interested in things religious, but he had been captured by a heretical movement called Manicheism, according to which there was not the One God, but rather two godheads, one good and benevolent, the other evil and malevolent.

One turning point in Augustine’s life came with his encounter with St. Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan, whose intellectual stance could match Augustine’s (it is difficult to find worthy interlocutors when you are an absolute genius…) and whose holiness deeply impressed him. Furthermore (and perhaps even more importantly), Augustine’s mother, Monica, was intensely Catholic, and she had shed countless tears over her son’s dissolute way of living – belonging in a heretical sect, being proud, and having several adventures with the gentle sex.

Her prayers were heard (and for this reason she has earned the role of patron saint of parents who are anguished for their children). Augustine felt the “shock of Grace” and converted to Catholicism, later to be ordained a bishop and to become one of the greatest figures of Christianity.

The experience of conversion is told by Augustine in the Confessions, one of his masterpieces where he narrates, without filters and without shame, what he was and how God led him to become what he would become. And it is told in fascinatingly sensory terms: “Late have I loved you, beauty so old and so new: late have I loved you. […] You called and cried out loud and shattered my deafness. You were radiant and resplendent, you put to flight my blindness. You were fragrant, and I drew in my breath and now pant after you. I tasted you, and I feel but hunger and thirst for you. You touched me, and I am set on fire to attain the peace which is yours”.

In fact, music had not been indifferent to Augustine’s experience of God and of faith. Already before converting, he had authored a fundamental treatise called De musica, in which he discusses mainly the rules of prosody. Later, he left memorable pages about the role of music in the faithful’s itinerary toward the “City of God”, as he called it.

Augustine certainly felt the power of music to draw the souls to transcendence; however, he was one of the few who was also alert to the “dangers” of music. The art of sounds captivates its listeners, but it may either lead them to God, or lead them astray, distract them. Augustine knew all this because he had experienced this. “Now, in those airs which Your words breathe soul into, when sung with a sweet and trained voice, do I somewhat repose; yet not so as to cling to them, but so as to free myself when I wish. […] I perceive that our minds are more devoutly and earnestly elevated into a flame of piety by the holy words themselves when they are thus sung, than when they are not. […] When I call to mind the tears I shed at the songs of Your Church, at the outset of my recovered faith, and how even now I am moved not by the singing but by what is sung, when they are sung with a clear and skilfully modulated voice, I then acknowledge the great utility of this custom. […] Yet when it happens to me to be more moved by the singing than by what is sung, I confess myself to have sinned criminally, and then I would rather not have heard the singing”.

This passage is rather typical for Augustine’s deep soul-searching, for his capability to delve deeply into the motivations and motives of the soul’s affections, and also for the contradictions inherent in the human mind, soul, and experience, which he outlines very clearly.

In spite of his perplexities, still, undeniably Augustine was fascinated by music. Indeed, he theorized wordless singing (the jubilatio or jubilus) as the highpoint of mystical exultation in God, and thus he paved the way for instrumental music in church.

It is therefore particularly fitting that his Confessions receive a musical frame with the masterly work of Fr Sulpizi recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album. Fr Sulpizi explains the reasons behind his undertaking – to write thirteen musical pieces to accompany the Confessions. In his words, “My goal was to enhance the experience of the text through an actor’s interpretation and to create reflective spaces by interspersing the reading of the chapters with music. By closing one’s eyes, listening to the words, and savoring their meaning as the notes flow, I hope to share the emotions evoked in me by the text and the music”.

In Fr Sulpizi’s work, an actor performs Augustine’s words, instead of the more usual silent act of private reading. This adds “something unique through the sound of the voice, which flows, vibrates, and intertwines with the sounds of the instruments”.

Fr Sulpizi considers Augustine’s reading of a Gospel episode, when John the Baptist identified himself as “the voice of one crying in the wilderness”. This passage has been commented upon by Augustine himself, noting that John is referred to as the “voice,” while the Lord is called the “Word,” as in “In the beginning was the Word”. “John, as the voice, exists only for a time, while Christ, as the Word, is eternal. The voice, a sound, becomes a word and conveys thought. While the sound fades away, the thought communicated by the word lingers in the listener’s soul. This concept underpins my effort to complete this work”. In fact, as Fr Sulpizi explains, “hearing the text through an interpreter allows for a richer appreciation of Augustine’s life story—so full of suffering, restlessness, and yearning for truth, ultimately fulfilled in the contemplation of creation”.

Furthermore, another aspect of Augustine’s thought which has deeply influenced Fr Sulpizi’s musical concept (“since 1975”, as he specifies), is what he calls the “characteristic musical idea.” This theory, inspired by Augustine’s reflections on time, identifies three faculties that enable us to understand time and existence within it: “expectation, which makes the future present; attention, which renders the present accessible; and memory, which makes the past present. Music, being inextricably linked to time, can be described as an event that colors time. To be perceived and appreciated, it must first be anticipated (awaited to reach the ear), then attentively listened to (to be internalized), and finally entrusted to memory. Without the mysterious preservation of memory, music fades, dissipates, appearing and disappearing almost into nothingness”. In this fashion, memory becomes crucial for preserving and recognizing the unique qualities of a musical idea, allowing it to be identified as a unified structure. Thus comes to light this touching, profound, deep, and fascinating composition, in which the reading of the thirteen books of the Confessions is framed by a corresponding number of musical items; different instrumental arrangements are employed, with each book concluding with a chorus of female voices.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads