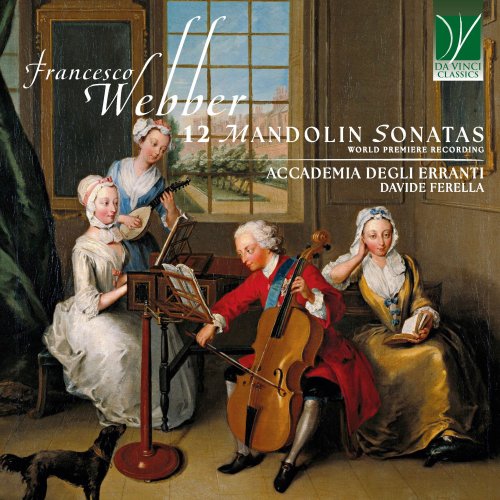

Accademia degli Erranti, Davide Ferella - Francesco Webber: 12 Mandolin Sonatas (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Accademia degli Erranti, Davide Ferella

- Title: Francesco Webber: 12 Mandolin Sonatas

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:22:47

- Total Size: 402 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Sonata I: I. Andante

02. Sonata I: II. Allegro

03. Sonata I: III. Menuet con spirito

04. Sonata II: I. Andante con spirito

05. Sonata II: II. Sostenuto

06. Sonata II: III. Giga

07. Sonata III: I. Amoroso

08. Sonata III: II. Allegro

09. Sonata III: III. Menuet

10. Sonata IV: I. Andante

11. Sonata IV: II. Larghetto

12. Sonata IV: III. Gavotta

13. Sonata V: I. Andante

14. Sonata V: II. Larghetto

15. Sonata V: III. Menuet

16. Sonata, Vol. I: I. Allegro

17. Sonata, Vol. I: II. Largo

18. Sonata, Vol. I: III. Giga

19. Sonata, Vol. II: I. Lento

20. Sonata, Vol. II: II. Allegro

21. Sonata, Vol. II: III. Menuet

22. Sonata, Vol. III: I. Larghetto

23. Sonata, Vol. III: II. Allegro

24. Sonata, Vol. III: III. Lento

25. Sonata, Vol. III: IV. Giga

26. Sonata IX: I. Largo

27. Sonata IX: II. Allegro assai

28. Sonata IX: III. Menuet

29. Sonata X: I. Largo

30. Sonata X: II. Allegro

31. Sonata X: III. Menuet spiritoso, ma non presto

32. Sonata XI: I. Vago

33. Sonata XI: II. Giga

34. Sonata XI: III. Sarabanda

35. Sonata XI: IV. Menuet con spirito

36. Sonata XII: I. Moderato

37. Sonata XII: II. Allegro

38. Sonata XII: III. Menuet con spirito

One of the most common – and frequently disturbing – clichés about Italianness is the triad pasta, pizza, mandolino. The two most beloved kinds of Italian food – both high in carbohydrates – are, somewhat incongruously, paired with a musical instrument, taken as a quintessential symbol for Italian music. Indeed, and at least in certain zones of Italy, the mandolin has been one of the most common instruments for decades. It also encouraged collective musicianship, and mandolin orchestras still continue to flourish in Italy. However, just as Italian cuisine vastly exceeds pasta and pizza, so do the mandolin’s history and repertoire massively transcend the boundaries of folk music.

In particular, the role of the mandolin in the Baroque and Rococo era needs still to be explored in a consistent and thorough fashion, even though scholars and performers such as Davide Rebuffa (on whose research the following pages will extensively draw) are doing a splendid works in bringing the secrets of eighteenth-century mandolin to light.

The early history of the mandolin bears witness to a variety of forms, shapes, and tunings. Thanks to its small size, dulcet tone, and versatility, the mandolin quickly acquired a place of preeminence both in instrumental works and as a coprotagonist of vocal music. Its golden age was the eighteenth century, when it attracted the attention of some of the most important musicians of the era, whilst in the Romantic period it began to be relegated within the smaller and more limited domain of amateur or domestic music-making.

The official birth date of the mandolin is 1627, when the first testimony of an instrument by this name is found, in the inventory of a luthier. Among hundreds of other instruments, there is just one mandolin, thus implying that it was a true novelty. Within the space of twenty years from then, however, other similar inventories attest to a much wider dissemination of the instrument, bearing witness to the popularity it quickly enjoyed.

From roughly the same time (1650-70) dates a manuscript by Agnolo Conti of Florence. It is the most ancient collection of mandolin music which survives to present-day, and it is conceived for a 4-course instrument. As concerns printed music, a couple of “balletti per la mandola” by Gasparo Cantarelli of Bologna (written for 5-course mandolin) is included within a method for guitar by Giovanni Pietro Ricci, printed in Rome in 1677; this is the first example of a printed publication for the mandolin. It is also interesting inasmuch as it suggests that the first mandolin players… were probably guitarists. Of course, the other main field whence mandolin players came was that of lute music, although, as Rebuffa correctly remarks, “it is […] interesting, and curious, that no examples of this kind have come to us in 17th century Italian lute books”. Thus, there is this double ascendency, in a manner of speaking: guitar playing, mainly at the dawn of mandolin music, and lute playing, in the decades between 17th and 18th century.

In the first decade of the 18th century, the mandolin crossed the Channel; from 1707 is the first witness of mandolin performances in London. Unsurprisingly, the mandolinist was an Italian, i.e. Francesco Conti. The wording of the concert’s advertisement is worth quoting, since it is both significant and curious: “Mr Hirckford’s Dancing Room in James Street, at the Hay Market: […] Signior [sic] Conti will play upon his great Theorbo, and on the Mandoline, an instrument not known yet”. Conti thus was a lutenist who doubled as a mandolin player, and the novelty of this instrument was expressly remarked. Another advertisement, on another paper, read: “Signior [sic] Conti is to play upon his Great Theorbo, and la Mandelitta, an Instrument hitherto unknown”. Here too the newness of the mandolin is highlighted, but the name by which it is indicated is very bizarre and unusual.

Indeed, names and terminology are – as can be expected – slightly confusing, particularly in the early stage of mandolin history. The most reliable source which can explain the difference between various forms and shapes of similar instruments is a work by Francesco Redi (1626-1690). Redi was in high repute already at his times, to the point that he was asked by the Accademia della Crusca (then, as today, the highest authority for all matters pertaining to the Italian language) to contribute to their vocabulary. Redi wrote: “The Pandora of modern musicians is an instrument with twelve strings [grouped] in six [double] courses. The mandolin has seven strings and four courses. The mandola has ten strings and five courses”. This clarifies both the difference and the kinship between these instruments.

The uncertainty found also in modern and contemporary discussions of these instruments is partly due to the wavering behaviour of some older authors. Fortunately, occasionally there were writers who sought to offer precise definitions, as was the case with Giampietro Pinaroli, who wrote, in the first half of the 18th century: “[The mandola] has ten strings [five double courses], of this number was also the ordinary ancient mandola; there is then the modern [mandola] and it contains twelve [strings], about which Father Filippo Bonanni of the Compagnia di Gesù was misled only assigning to it four strings, and it brings forth a very treble sound”.

The city whence the mandolin culture radiated was Rome, which was home to a very high number of luthiers, many of whom were of German origins – to the point that, until present-day, there is a Via dei Leutari (Luthiers’ Street) in the center of the Italian capital. In the eighteenth century, the most important luthiers specialized in mandolins were Giovanni Smorsone, David Tecchler, Benedetto Gualzatta, and Gaspar Ferrari. Arguably, therefore, also Francesco Webber (with an Italian first name and German family name) belonged in this particular subculture, and brought it successfully to Britain.

01. Sonata I: I. Andante

02. Sonata I: II. Allegro

03. Sonata I: III. Menuet con spirito

04. Sonata II: I. Andante con spirito

05. Sonata II: II. Sostenuto

06. Sonata II: III. Giga

07. Sonata III: I. Amoroso

08. Sonata III: II. Allegro

09. Sonata III: III. Menuet

10. Sonata IV: I. Andante

11. Sonata IV: II. Larghetto

12. Sonata IV: III. Gavotta

13. Sonata V: I. Andante

14. Sonata V: II. Larghetto

15. Sonata V: III. Menuet

16. Sonata, Vol. I: I. Allegro

17. Sonata, Vol. I: II. Largo

18. Sonata, Vol. I: III. Giga

19. Sonata, Vol. II: I. Lento

20. Sonata, Vol. II: II. Allegro

21. Sonata, Vol. II: III. Menuet

22. Sonata, Vol. III: I. Larghetto

23. Sonata, Vol. III: II. Allegro

24. Sonata, Vol. III: III. Lento

25. Sonata, Vol. III: IV. Giga

26. Sonata IX: I. Largo

27. Sonata IX: II. Allegro assai

28. Sonata IX: III. Menuet

29. Sonata X: I. Largo

30. Sonata X: II. Allegro

31. Sonata X: III. Menuet spiritoso, ma non presto

32. Sonata XI: I. Vago

33. Sonata XI: II. Giga

34. Sonata XI: III. Sarabanda

35. Sonata XI: IV. Menuet con spirito

36. Sonata XII: I. Moderato

37. Sonata XII: II. Allegro

38. Sonata XII: III. Menuet con spirito

One of the most common – and frequently disturbing – clichés about Italianness is the triad pasta, pizza, mandolino. The two most beloved kinds of Italian food – both high in carbohydrates – are, somewhat incongruously, paired with a musical instrument, taken as a quintessential symbol for Italian music. Indeed, and at least in certain zones of Italy, the mandolin has been one of the most common instruments for decades. It also encouraged collective musicianship, and mandolin orchestras still continue to flourish in Italy. However, just as Italian cuisine vastly exceeds pasta and pizza, so do the mandolin’s history and repertoire massively transcend the boundaries of folk music.

In particular, the role of the mandolin in the Baroque and Rococo era needs still to be explored in a consistent and thorough fashion, even though scholars and performers such as Davide Rebuffa (on whose research the following pages will extensively draw) are doing a splendid works in bringing the secrets of eighteenth-century mandolin to light.

The early history of the mandolin bears witness to a variety of forms, shapes, and tunings. Thanks to its small size, dulcet tone, and versatility, the mandolin quickly acquired a place of preeminence both in instrumental works and as a coprotagonist of vocal music. Its golden age was the eighteenth century, when it attracted the attention of some of the most important musicians of the era, whilst in the Romantic period it began to be relegated within the smaller and more limited domain of amateur or domestic music-making.

The official birth date of the mandolin is 1627, when the first testimony of an instrument by this name is found, in the inventory of a luthier. Among hundreds of other instruments, there is just one mandolin, thus implying that it was a true novelty. Within the space of twenty years from then, however, other similar inventories attest to a much wider dissemination of the instrument, bearing witness to the popularity it quickly enjoyed.

From roughly the same time (1650-70) dates a manuscript by Agnolo Conti of Florence. It is the most ancient collection of mandolin music which survives to present-day, and it is conceived for a 4-course instrument. As concerns printed music, a couple of “balletti per la mandola” by Gasparo Cantarelli of Bologna (written for 5-course mandolin) is included within a method for guitar by Giovanni Pietro Ricci, printed in Rome in 1677; this is the first example of a printed publication for the mandolin. It is also interesting inasmuch as it suggests that the first mandolin players… were probably guitarists. Of course, the other main field whence mandolin players came was that of lute music, although, as Rebuffa correctly remarks, “it is […] interesting, and curious, that no examples of this kind have come to us in 17th century Italian lute books”. Thus, there is this double ascendency, in a manner of speaking: guitar playing, mainly at the dawn of mandolin music, and lute playing, in the decades between 17th and 18th century.

In the first decade of the 18th century, the mandolin crossed the Channel; from 1707 is the first witness of mandolin performances in London. Unsurprisingly, the mandolinist was an Italian, i.e. Francesco Conti. The wording of the concert’s advertisement is worth quoting, since it is both significant and curious: “Mr Hirckford’s Dancing Room in James Street, at the Hay Market: […] Signior [sic] Conti will play upon his great Theorbo, and on the Mandoline, an instrument not known yet”. Conti thus was a lutenist who doubled as a mandolin player, and the novelty of this instrument was expressly remarked. Another advertisement, on another paper, read: “Signior [sic] Conti is to play upon his Great Theorbo, and la Mandelitta, an Instrument hitherto unknown”. Here too the newness of the mandolin is highlighted, but the name by which it is indicated is very bizarre and unusual.

Indeed, names and terminology are – as can be expected – slightly confusing, particularly in the early stage of mandolin history. The most reliable source which can explain the difference between various forms and shapes of similar instruments is a work by Francesco Redi (1626-1690). Redi was in high repute already at his times, to the point that he was asked by the Accademia della Crusca (then, as today, the highest authority for all matters pertaining to the Italian language) to contribute to their vocabulary. Redi wrote: “The Pandora of modern musicians is an instrument with twelve strings [grouped] in six [double] courses. The mandolin has seven strings and four courses. The mandola has ten strings and five courses”. This clarifies both the difference and the kinship between these instruments.

The uncertainty found also in modern and contemporary discussions of these instruments is partly due to the wavering behaviour of some older authors. Fortunately, occasionally there were writers who sought to offer precise definitions, as was the case with Giampietro Pinaroli, who wrote, in the first half of the 18th century: “[The mandola] has ten strings [five double courses], of this number was also the ordinary ancient mandola; there is then the modern [mandola] and it contains twelve [strings], about which Father Filippo Bonanni of the Compagnia di Gesù was misled only assigning to it four strings, and it brings forth a very treble sound”.

The city whence the mandolin culture radiated was Rome, which was home to a very high number of luthiers, many of whom were of German origins – to the point that, until present-day, there is a Via dei Leutari (Luthiers’ Street) in the center of the Italian capital. In the eighteenth century, the most important luthiers specialized in mandolins were Giovanni Smorsone, David Tecchler, Benedetto Gualzatta, and Gaspar Ferrari. Arguably, therefore, also Francesco Webber (with an Italian first name and German family name) belonged in this particular subculture, and brought it successfully to Britain.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads