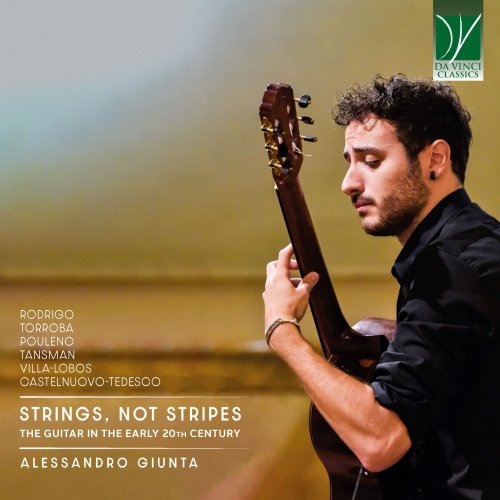

Alessandro Giunta - Strings, not Stripes: The Guitar in the Early 20th Century (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Alessandro Giunta

- Title: Strings, not Stripes: The Guitar in the Early 20th Century

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Guitar

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:58:02

- Total Size: 183 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Cinq Préludes, W419: No. 1

02. Cinq Préludes, W419: No. 2

03. Cinq Préludes, W419: No. 3

04. Cinq Préludes, W419: No. 4

05. Cinq Préludes, W419: No. 5

06. Tiento Antiguo

07. Burgalesa

08. Madroños

09. Sarabande, FP179

10. Cavatina Suite: No. 1, Preludio

11. Cavatina Suite: No. 2, Sarabande

12. Cavatina Suite: No. 3, Scherzino

13. Cavatina Suite: No. 4, Barcarole

14. Cavatina Suite: Danza Pomposa

15. Capriccio Diabolico, Op. 85 (Omaggio a Paganini)

This Da Vinci Classics album is a polyphony of voices gathering some of the most important composers of guitar works in the twentieth century. They came from very different backgrounds: from Brazil to Spain – the guitar’s homeland –, from France to Poland and Italy. Their styles are also very varied, although all of them are exquisite representatives of the current of composers who chose to maintain a bond with tonality and harmony, while innovating the tonal language from the inside.

But perhaps the main unifying element which keeps together most composers featured here and the works recorded and performed here is the concept underlying the choice just mentioned. The leading principle for these musicians was that of a “renaissance” of the guitar founded on the idea of Neoclassicism. For these composers, the guitar was an “expressive instrument”, in both meanings of these words: an instrument for expressing their soul, and a musical instrument with a great potential for expressiveness.

The guitar, being a plucked-string instrument, was also an ideal bridge connecting modernity with antiquity, since plucked-string instruments (such as the lyra or the cithara) are among the oldest instruments in human history, and other plucked-string instruments (such as the lute) are iconic symbols for other past (though more recent) eras.

Employed by modern composers and in the hands of contemporary musicians, thus, the guitar becomes a vehicle for accessing, with a critical and inspired eye, a past world and its music. This is the case, for example, with Tiento antiguo, with Poulenc’s Sarabande, which is inspired by tunes whose roots delve deep (to the point that strains of Gregorian melodies are found here), with Tansman’s Cavatina.

No less important is the connection with other kinds of roots: not just those of the “classical” repertoire and early European music, but also the roots of a nation’s own music. This is the case with the music by Torroba, and with Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Capriccio diabolico. This last piece is deeply influenced by the aesthetics and by the principles of what is known in Italy as “generazione dell’Ottanta”, i.e. the group of great Italian composers who were born in the 1880s and who contributed highly to the rebirth and renaissance of Italian instrumental music in the first part of the twentieth century. This rebirth, in turn, required a greater awareness of one’s past; to that “generation” is due, in fact, the rediscovery of the instrumental tradition of baroque Italy (Corelli, Scarlatti, Vivaldi, to name but the most important of these musicians).

Thanks to the flexibility of the guitar as an instrument, and to its proximity to timbres typical for early music (such as the lute’s), but also to its universal dissemination, the guitar was the ideal instrument for enacting these multiple rediscoveries in a creative, artistic fashion. All over the world, composers in the first half of the twentieth century found in this instrument a great resource. It was needed at the dawn of the century, with its explosion of novelties, its enthusiasm, but also the crumbling of many deeply-held convictions; it was even more needed after the disasters and tragedies of World War I – when the essential, bare sound of the guitar was perhaps best suited to express the naked reality of the post-war period; it was needed when the burgeoning musicological disciplines brought a novel awareness about the “history” of music, its past, its value, and the principles of older works.

Finally, another red thread of this album is represented by the figure of Andrés Segovia. The role of Segovia in the “guitar Renaissance” of the twentieth century is unparalleled. An astonishing virtuoso and a musician of extraordinary refinement, Segovia commissioned countless guitar works to a plethora of composers, including some of the greatest; he premiered many of them; he inspired and motivated artists who were thrilled by the exceptional traits of his performances and of his understanding of music. With him, the guitar left behind its former status as a niche instrument, as an instrument suited mainly for exotic evocations of Iberia, and became a concert instrument proper, a true protagonist of the concert life.

Segovia was the dedicatee of Heitor Villa Lobos’ Cinq Préludes. Written in 1940, they represent Villa Lobos’ swan song as concerns guitar music. Although Villa Lobos is unanimously acknowledged as a great composer of guitar music, at the time of the Préludes’ composition he had been leaving the guitar aside for years. The merit for bringing Villa Lobos back to guitar music is to be ascribed to Segovia, whom Villa Lobos had met a few years before.

The Preludes were dedicated to “Mindinha”, Villa Lobos’ wife. But in a written document, Segovia speaks of six Preludes instead of the five we now have. There has been much dispute on this. There are witnesses (Turibio Santos and José Vieira Brandão) who claim to have seen the missing sixth prelude; indeed, reportedly, Vieira Brandão considered it “the best of all”, “o mais bonito de todos”. However, there is some skepticism among musicologists as to whether this sixth Prelude ever existed.

There are still other mysteries connected with this collection. The titles, all “homages” paid to someone, by which the several movements are referred to have no known source. They probably originate from Villa-Lobos’ circle, if not directly from him, but their origin remains a matter of speculation. The first is known as a “Homage to the dwellers of the Brazilian sertão”, the vast, semi-arid region in the interior of the country, characterized by its rugged terrain, thorny vegetation (caatinga), and periodic droughts.

The second is a homage to the “Marauder of Rio de Janeiro”; here we also hear a capoeira melody. Capoeira is a traditional dance of the Brazilian Africans, which resembles a martial art in its graceful yet energetic moves. There is also a suggestive imitation of the berimbau, an African instrument with just one metal string. The third is a homage to Bach, a favourite composer of both Villa Lobos and Segovia himself. It will be recalled that Villa Lobos had authored several Bachianas Brasileiras, in which he attempted to combine the rigour and balance of the German Baroque composer with the vivacity and liveliness of Brazilian music.

Brazil is the protagonist of the fourth Prelude, in which Villa Lobos’ constant interest in the natives’ culture is displayed, whilst the fifth Prelude returns to urban contexts. It is a “Homage to social life”, and in particular it is dedicated to “the fresh young boys and girls who go to concerts and to the theatre in Rio”.

Similar to Villa Lobos, also Joaquín Rodrigo was enamoured of the guitar but had quit composing for it for some years; and here too the piece recorded in this album, Tiento Antiguo, is the composer’s return to the instrument. Written in 1947 and dedicated to a German guitarist, Siegfried Behrend, it seemingly should evoke the sound and style of the vihuela; however, on close scrutiny this does not appear clearly; rather, the musical imagery seems to derive more directly from flamenco music.

The two pieces by Moreno Torroba recorded here are among the best known in his guitar output: Burgalésa (1928) is a homage to the Castilian city of Burgos, evoked as from afar in time and space. Madroños is more colourful and folklike, with numerous effects of spatialization.

Francis Poulenc’s Sarabande is yet another evocation of distant times and places, fittingly corresponding to Poulenc’s interest in Neoclassicism. Written in 1960, it reflects Poulenc’s characteristic style, blending elegance with emotional depth. Although traditionally Sarabandes are in a 3/4 metre, this one wavers between 3, 4, and even 5 beats per bar, but the result is very harmonious due to Poulenc’s masterful handling of the musical material. It is dedicated to Ida Presti, a phenomenal guitarist who was widely regarded as one of the greatest players of her time and had an influential presence in classical guitar circles.

Other dances come next, including another Sarabande, in the bizarrely-titled Suite Cavatina by the Polish-born composer Alexandre Tansman. This work earned him the first prize in the Accademia Chigiana’s International Competition for works for solo guitar in 1951, and was a particular favourite of Segovia. Its premiere took place in 1952 at the Chigiana in Siena.

The work’s name, as has been said, is somewhat incongruous, since Cavatina technically is a major character’s debut aria in Italian operas. Originally conceived in four movements, it was later expanded to include the Danza Pomposa, written by Tansman on Segovia’s explicit request. The allusion to Italy found in the title is mirrored by particular traits found in the entire composition. For instance, the Barcarolle is an evocation of Venice and of the gondola songs. At the same time, it is also a homage to Frédéric Chopin, who composed a very famous Barcarolle for the piano, and who shared with Tansman both the Polish roots and the French acquired culture. Recurring elements in the entire Suite are the “key” of E (intended as closer to modality than to tonality) and the use of dactylic rhythms, which were frequently adopted in the music of the past to signify energy and liveliness. Tansman’s work is a notable example of guitar composition which does not reference Spanish music or topoi.

Another homage to Italy, or at least to an Italian musician, comes from the Italian composer whose work closes this album. Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco was an Italian Jew who had to flee Italy in consideration of the racial persecutions of the Fascist regime, finding his new homeland in the States, where he would become an appreciated composer of film music. He wrote extensively for the guitar; his impressive series of 24 Preludes and Fugues, Les guitares bien tempérées, was dedicated to Ida Presti, along with Alexandre Lagoya.

His Capriccio diabolico – which also exists in an unpublished version for guitar with orchestral accompaniment – is a homage in the same vein as those by Villa Lobos. In this case, the homage’s recipient is none other than Niccolò Paganini, who wrote extensively for the guitar even though his first instrument was, obviously, the violin.

Capriccio diabolico composed in 1935 at Segovia’s prompting, is performed here in a manner close to its original form, omitting the opening-bar quotations of Paganini’s famous La Campanella theme. A variety of techniques is explored in it; thus, the homage to Paganini extends well beyond the initial quotation, becoming a symbol of the performer’s mastery across a broad range of technical demands. Taken together, these pieces form a mosaic whose collective examination offers a panorama of the main trends in twentieth-century guitar music.

01. Cinq Préludes, W419: No. 1

02. Cinq Préludes, W419: No. 2

03. Cinq Préludes, W419: No. 3

04. Cinq Préludes, W419: No. 4

05. Cinq Préludes, W419: No. 5

06. Tiento Antiguo

07. Burgalesa

08. Madroños

09. Sarabande, FP179

10. Cavatina Suite: No. 1, Preludio

11. Cavatina Suite: No. 2, Sarabande

12. Cavatina Suite: No. 3, Scherzino

13. Cavatina Suite: No. 4, Barcarole

14. Cavatina Suite: Danza Pomposa

15. Capriccio Diabolico, Op. 85 (Omaggio a Paganini)

This Da Vinci Classics album is a polyphony of voices gathering some of the most important composers of guitar works in the twentieth century. They came from very different backgrounds: from Brazil to Spain – the guitar’s homeland –, from France to Poland and Italy. Their styles are also very varied, although all of them are exquisite representatives of the current of composers who chose to maintain a bond with tonality and harmony, while innovating the tonal language from the inside.

But perhaps the main unifying element which keeps together most composers featured here and the works recorded and performed here is the concept underlying the choice just mentioned. The leading principle for these musicians was that of a “renaissance” of the guitar founded on the idea of Neoclassicism. For these composers, the guitar was an “expressive instrument”, in both meanings of these words: an instrument for expressing their soul, and a musical instrument with a great potential for expressiveness.

The guitar, being a plucked-string instrument, was also an ideal bridge connecting modernity with antiquity, since plucked-string instruments (such as the lyra or the cithara) are among the oldest instruments in human history, and other plucked-string instruments (such as the lute) are iconic symbols for other past (though more recent) eras.

Employed by modern composers and in the hands of contemporary musicians, thus, the guitar becomes a vehicle for accessing, with a critical and inspired eye, a past world and its music. This is the case, for example, with Tiento antiguo, with Poulenc’s Sarabande, which is inspired by tunes whose roots delve deep (to the point that strains of Gregorian melodies are found here), with Tansman’s Cavatina.

No less important is the connection with other kinds of roots: not just those of the “classical” repertoire and early European music, but also the roots of a nation’s own music. This is the case with the music by Torroba, and with Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Capriccio diabolico. This last piece is deeply influenced by the aesthetics and by the principles of what is known in Italy as “generazione dell’Ottanta”, i.e. the group of great Italian composers who were born in the 1880s and who contributed highly to the rebirth and renaissance of Italian instrumental music in the first part of the twentieth century. This rebirth, in turn, required a greater awareness of one’s past; to that “generation” is due, in fact, the rediscovery of the instrumental tradition of baroque Italy (Corelli, Scarlatti, Vivaldi, to name but the most important of these musicians).

Thanks to the flexibility of the guitar as an instrument, and to its proximity to timbres typical for early music (such as the lute’s), but also to its universal dissemination, the guitar was the ideal instrument for enacting these multiple rediscoveries in a creative, artistic fashion. All over the world, composers in the first half of the twentieth century found in this instrument a great resource. It was needed at the dawn of the century, with its explosion of novelties, its enthusiasm, but also the crumbling of many deeply-held convictions; it was even more needed after the disasters and tragedies of World War I – when the essential, bare sound of the guitar was perhaps best suited to express the naked reality of the post-war period; it was needed when the burgeoning musicological disciplines brought a novel awareness about the “history” of music, its past, its value, and the principles of older works.

Finally, another red thread of this album is represented by the figure of Andrés Segovia. The role of Segovia in the “guitar Renaissance” of the twentieth century is unparalleled. An astonishing virtuoso and a musician of extraordinary refinement, Segovia commissioned countless guitar works to a plethora of composers, including some of the greatest; he premiered many of them; he inspired and motivated artists who were thrilled by the exceptional traits of his performances and of his understanding of music. With him, the guitar left behind its former status as a niche instrument, as an instrument suited mainly for exotic evocations of Iberia, and became a concert instrument proper, a true protagonist of the concert life.

Segovia was the dedicatee of Heitor Villa Lobos’ Cinq Préludes. Written in 1940, they represent Villa Lobos’ swan song as concerns guitar music. Although Villa Lobos is unanimously acknowledged as a great composer of guitar music, at the time of the Préludes’ composition he had been leaving the guitar aside for years. The merit for bringing Villa Lobos back to guitar music is to be ascribed to Segovia, whom Villa Lobos had met a few years before.

The Preludes were dedicated to “Mindinha”, Villa Lobos’ wife. But in a written document, Segovia speaks of six Preludes instead of the five we now have. There has been much dispute on this. There are witnesses (Turibio Santos and José Vieira Brandão) who claim to have seen the missing sixth prelude; indeed, reportedly, Vieira Brandão considered it “the best of all”, “o mais bonito de todos”. However, there is some skepticism among musicologists as to whether this sixth Prelude ever existed.

There are still other mysteries connected with this collection. The titles, all “homages” paid to someone, by which the several movements are referred to have no known source. They probably originate from Villa-Lobos’ circle, if not directly from him, but their origin remains a matter of speculation. The first is known as a “Homage to the dwellers of the Brazilian sertão”, the vast, semi-arid region in the interior of the country, characterized by its rugged terrain, thorny vegetation (caatinga), and periodic droughts.

The second is a homage to the “Marauder of Rio de Janeiro”; here we also hear a capoeira melody. Capoeira is a traditional dance of the Brazilian Africans, which resembles a martial art in its graceful yet energetic moves. There is also a suggestive imitation of the berimbau, an African instrument with just one metal string. The third is a homage to Bach, a favourite composer of both Villa Lobos and Segovia himself. It will be recalled that Villa Lobos had authored several Bachianas Brasileiras, in which he attempted to combine the rigour and balance of the German Baroque composer with the vivacity and liveliness of Brazilian music.

Brazil is the protagonist of the fourth Prelude, in which Villa Lobos’ constant interest in the natives’ culture is displayed, whilst the fifth Prelude returns to urban contexts. It is a “Homage to social life”, and in particular it is dedicated to “the fresh young boys and girls who go to concerts and to the theatre in Rio”.

Similar to Villa Lobos, also Joaquín Rodrigo was enamoured of the guitar but had quit composing for it for some years; and here too the piece recorded in this album, Tiento Antiguo, is the composer’s return to the instrument. Written in 1947 and dedicated to a German guitarist, Siegfried Behrend, it seemingly should evoke the sound and style of the vihuela; however, on close scrutiny this does not appear clearly; rather, the musical imagery seems to derive more directly from flamenco music.

The two pieces by Moreno Torroba recorded here are among the best known in his guitar output: Burgalésa (1928) is a homage to the Castilian city of Burgos, evoked as from afar in time and space. Madroños is more colourful and folklike, with numerous effects of spatialization.

Francis Poulenc’s Sarabande is yet another evocation of distant times and places, fittingly corresponding to Poulenc’s interest in Neoclassicism. Written in 1960, it reflects Poulenc’s characteristic style, blending elegance with emotional depth. Although traditionally Sarabandes are in a 3/4 metre, this one wavers between 3, 4, and even 5 beats per bar, but the result is very harmonious due to Poulenc’s masterful handling of the musical material. It is dedicated to Ida Presti, a phenomenal guitarist who was widely regarded as one of the greatest players of her time and had an influential presence in classical guitar circles.

Other dances come next, including another Sarabande, in the bizarrely-titled Suite Cavatina by the Polish-born composer Alexandre Tansman. This work earned him the first prize in the Accademia Chigiana’s International Competition for works for solo guitar in 1951, and was a particular favourite of Segovia. Its premiere took place in 1952 at the Chigiana in Siena.

The work’s name, as has been said, is somewhat incongruous, since Cavatina technically is a major character’s debut aria in Italian operas. Originally conceived in four movements, it was later expanded to include the Danza Pomposa, written by Tansman on Segovia’s explicit request. The allusion to Italy found in the title is mirrored by particular traits found in the entire composition. For instance, the Barcarolle is an evocation of Venice and of the gondola songs. At the same time, it is also a homage to Frédéric Chopin, who composed a very famous Barcarolle for the piano, and who shared with Tansman both the Polish roots and the French acquired culture. Recurring elements in the entire Suite are the “key” of E (intended as closer to modality than to tonality) and the use of dactylic rhythms, which were frequently adopted in the music of the past to signify energy and liveliness. Tansman’s work is a notable example of guitar composition which does not reference Spanish music or topoi.

Another homage to Italy, or at least to an Italian musician, comes from the Italian composer whose work closes this album. Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco was an Italian Jew who had to flee Italy in consideration of the racial persecutions of the Fascist regime, finding his new homeland in the States, where he would become an appreciated composer of film music. He wrote extensively for the guitar; his impressive series of 24 Preludes and Fugues, Les guitares bien tempérées, was dedicated to Ida Presti, along with Alexandre Lagoya.

His Capriccio diabolico – which also exists in an unpublished version for guitar with orchestral accompaniment – is a homage in the same vein as those by Villa Lobos. In this case, the homage’s recipient is none other than Niccolò Paganini, who wrote extensively for the guitar even though his first instrument was, obviously, the violin.

Capriccio diabolico composed in 1935 at Segovia’s prompting, is performed here in a manner close to its original form, omitting the opening-bar quotations of Paganini’s famous La Campanella theme. A variety of techniques is explored in it; thus, the homage to Paganini extends well beyond the initial quotation, becoming a symbol of the performer’s mastery across a broad range of technical demands. Taken together, these pieces form a mosaic whose collective examination offers a panorama of the main trends in twentieth-century guitar music.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads