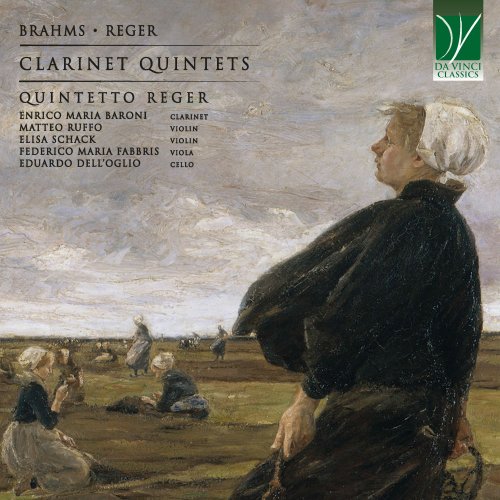

Quintetto Reger, Enrico Maria Baroni, Matteo Ruffo, Elisa Schack, Federico Maria Fabbris, Eduardo Dell’Oglio, Johannes Brahms, Max Reger, Eduardo Dell'Oglio - Johannes Brahms, Max Reger: Clarinet Quintets (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Quintetto Reger, Enrico Maria Baroni, Matteo Ruffo, Elisa Schack, Federico Maria Fabbris, Eduardo Dell’Oglio, Johannes Brahms, Max Reger, Eduardo Dell'Oglio

- Title: Johannes Brahms, Max Reger: Clarinet Quintets

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:14:50

- Total Size: 361 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115: I. Allegro

02. Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115: II. Adagio

03. Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115: III. Andantino

04. Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115: IV. Con moto

06. Clarinet Quintet in A Major, Op. 146: II. Vivace

07. Clarinet Quintet in A Major, Op. 146: III. Largo

08. Clarinet Quintet in A Major, Op. 146: IV. Poco allegretto

Human beings learn by imitation. And, indeed, the concept of imitatio has inspired many endeavours, not only in the artistic field, in the Western world. One may mention the fact that the Imitatio Christi, the “imitation of Christ”, was one of the most beloved and widely read spiritual works from the time of its creation until a short time ago; and, for many centuries, imitatio was a core concept not only in the education of young people, but also in the evaluation of works created by adults. Today’s world prizes originality highly; not so was it in the past, when a piece of art, or a treatise, could be valued precisely by virtue of its consistency with tradition. By imitating the great, an artist showed humility, which was considered as an important human value and virtue; and it was believed that that imitation could result in new works of art with their own dignity and value. And so it was, indeed; this principle was proved correct countless times, and artworks born out of the principle of imitation became masterpieces in their own right.

And even though both works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album fully belong in the aesthetics of the late Romanticism – that is, of the period when this paradigm was shaken, and originality became the trademark of genius – they still refer clearly to identifiable models, whilst maintaining their own distinctive individuality. The model underlying both masterpieces is another masterpiece, i.e. Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet KV 581; and, in Reger’s case, it is evident that also Brahms’ own Clarinet Quintet was considered by the composer as a model to be followed in turn.

And this brings us to another interesting point. In the history of music, there are genres with hundreds of masterpieces. Whilst there are, for instance, some Piano Sonatas which have been more influential than others in establishing turning points of music history, it would be very problematic to name “one” Piano Sonata as the cornerstone of this whole genre. Certainly, the piano repertoire would definitely not be the same without Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas, and, among them, there are some which represent unavoidable paradigms against which other works are tested. Still, even Beethoven’s Sonatas are thirty-two, and it is their joint influence which has determined their paradigmatic status.

Not so in the case of the genre “clarinet quintet”. Firstly, the clarinet is a relatively young instrument, even though it builds on the foundations of earlier instruments with simple reed. This allowed even great masters such as Mozart (or Brahms himself!) to be surprised by its possibilities, especially when they encountered genius performers on that instrument. Secondly, chamber music itself, as we intend it today, was a comparatively new phenomenon. Of course, playing together has been the norm for most of music’s history throughout times and places. But the concept of an elevated, artistic music-making, which goes beyond the boundaries of the bourgeois home and of the circle of amateur musicians, is a concept which emerged only gradually, and not without difficulty.

Thus, even though Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet is not the first example of a work for this specific ensemble (i.e. a clarinet and a string quartet), it is certainly the first absolute masterpiece to have been written for it. And it immediately became the unavoidable benchmark and reference point for all other pieces written in this genre. Mozart had been prompted to compose it by his encounter with a genius clarinetist, who had unveiled to him the enormous potential of this instrument. And Mozart made full use of the clarinet and of its genius player’s capabilities, writing a perfect work which remains among the highest creations of its composer.

Approximately a century later (Mozart’s Quintet was composed in 1789), in 1891, another encounter between a genius player and a genius composer would yield another absolute masterpiece. In the meanwhile, several other works had been written for clarinet and string quartet, among them, most notably, a Quintet by Carl Maria von Weber, who had a particular fondness for this instrument. Possibly for this reason, he reserved for the clarinet a soloistic part, which effectively opposes it to the quartet, seen as almost the miniature orchestra for a solo clarinet concerto. By way of contrast, Mozart had created a truly egalitarian milieu, in which all instruments have their share of beauty to play and to offer. Clearly enough, the different timbre of the clarinet stands out with respect to the other instruments, and therefore something like a soloistic approach is unavoidable. But, generally speaking, this masterpiece is a real example of chamber music, whose enchantment results from the cooperation of all involved.

Johannes Brahms was by no means decrepit when he decided that he had had enough of composing. He was still comparatively young, and his creativity was not displaying any signs of waning. However, he had decided that his compositional career was over, and that he would dedicate the remainder of his years to performance, both as a pianist and as a conductor.

However, he had not foreseen the impact that the performance of Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet by Richard Mühlfeld would have meant for him. Mühlfeld was the clarinetist of the Meiningen Hofkapelle, and his playing enthused Brahms to the point that he reconsidered his decision. Brahms wrote about Mühlfeld’s performance to his longtime friend and confidante Clara Schumann, and he soon set to write his own Clarinet Quintet, along with a Clarinet trio (with piano and cello). It should be mentioned that Mühlfeld would also provoke Brahms to compose the two magnificent Clarinet Sonatas op. 120, once more drawing the composer out of another period of artistic silence.

Mühlfeld, indeed, must have been a really exceptional musician, since not only did his music conquer Brahms so powerfully, but it also convinced Joseph Joachim to contravene one of the most rigid rules he had imposed on his concert series in Berlin. Normally, only music for string quartet could be played there; but the impression of Mühlfeld’s playing led Joachim to include this work in the otherwise strings-only series. The piece was tried out by Joachim and his Quartet in a semiprivate context; then, another tryout was undertaken, of an alternative version with a second viola instead of the clarinet. This may puzzle our readers: if the Quintet had been tailored upon Mühlfeld’s gifts, why should one replace the clarinet with a viola? Furthermore, wouldn’t the clarinet part be drowned by the other strings’ thick texture, if not helped to stand out by its different timbre? These are not idle questions, since in fact the version with two violas has rarely been performed. However, that tryout was also exceptional, inasmuch as Joachim himself played the solo viola part, accompanied by the Rose Quartet; that Quartet would be Mühlfeld’s partner in the actual public premiere of the work.

And Brahms’ Quintet was to become in turn a paradigm of the literature for this specific ensemble. Arguably, moreover, we do not owe to Mühlfeld “just” the four masterpieces with clarinet written by Brahms in his last years, but also the other works of that same period. And this is saying something.

When Max Reger decided to write his own Clarinet Quintet, he took Mozart’s Quintet as his model in turn, but, at the same time, he also looked at Brahms’ Quintet as at his second, and more recent, reference point. All three masterpieces have in common the fact of being some of the last fruits of their composers’ creativity: Mozart and Brahms were to outlive the composition of their Quintets by a couple of years, while for Reger this was to be his very last work. Indeed, death caught him before the work’s premiere, which took place posthumously and in memory of its composer. Reger explicitly acknowledged his debt toward Mozart and his music, writing to a publisher that contemporaneous music was lacking “a Mozart”. And the reference to Mozart (and to Brahms) is evident even at the macro level, since all three composers decided to set the last movement of their works as a theme with variations. Reger’s initial project to write one such work did not blossom immediately into a finished piece; this had to wait for a few years, until, in the summer of 1915, he was ready to accept the challenge. Like Brahms, and – again like him – mainly with the purpose in mind to make the score more palatable to the larger public, Reger planned for a version as a string quintet with two violas to be realized; however, he did not live enough to see the work through its whole publication process. The dedicatee of Reger’s work is a further element of continuity with Brahms, since Carl Wendling, an esteemed friend of the composer, had studied with Joseph Joachim and had received the dedication of several other masterpieces by Reger.

Both Quintets seem to mirror a quality which might derive from their composers’ stage of life, but also from the inherent tinge of the clarinet’s sound: i.e. a penchant for meditativeness, for contemplation, for an elegiac reflection on time past, with some regrets perhaps, but also with a touching wisdom and profundity. Moments of levity and grace are certainly not missing, and even hints at humour and at the liveliness and energy of youth; however, they are transfigured by a gaze, as it were, from a distance; by the gaze of composers who were entrusting to the clarinet’s mellow and poetic sound the last words of their artistic activity, and the creative testament of their lives. The appealing quality of these pieces thus resides in their capability to evoke something sublime and enchanting at the same time, and of suggesting a world of musical imagination in which deep reflections on the meaning of life can take place, but always with a smile tinged by melancholia and nostalgia.

01. Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115: I. Allegro

02. Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115: II. Adagio

03. Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115: III. Andantino

04. Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115: IV. Con moto

06. Clarinet Quintet in A Major, Op. 146: II. Vivace

07. Clarinet Quintet in A Major, Op. 146: III. Largo

08. Clarinet Quintet in A Major, Op. 146: IV. Poco allegretto

Human beings learn by imitation. And, indeed, the concept of imitatio has inspired many endeavours, not only in the artistic field, in the Western world. One may mention the fact that the Imitatio Christi, the “imitation of Christ”, was one of the most beloved and widely read spiritual works from the time of its creation until a short time ago; and, for many centuries, imitatio was a core concept not only in the education of young people, but also in the evaluation of works created by adults. Today’s world prizes originality highly; not so was it in the past, when a piece of art, or a treatise, could be valued precisely by virtue of its consistency with tradition. By imitating the great, an artist showed humility, which was considered as an important human value and virtue; and it was believed that that imitation could result in new works of art with their own dignity and value. And so it was, indeed; this principle was proved correct countless times, and artworks born out of the principle of imitation became masterpieces in their own right.

And even though both works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album fully belong in the aesthetics of the late Romanticism – that is, of the period when this paradigm was shaken, and originality became the trademark of genius – they still refer clearly to identifiable models, whilst maintaining their own distinctive individuality. The model underlying both masterpieces is another masterpiece, i.e. Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet KV 581; and, in Reger’s case, it is evident that also Brahms’ own Clarinet Quintet was considered by the composer as a model to be followed in turn.

And this brings us to another interesting point. In the history of music, there are genres with hundreds of masterpieces. Whilst there are, for instance, some Piano Sonatas which have been more influential than others in establishing turning points of music history, it would be very problematic to name “one” Piano Sonata as the cornerstone of this whole genre. Certainly, the piano repertoire would definitely not be the same without Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas, and, among them, there are some which represent unavoidable paradigms against which other works are tested. Still, even Beethoven’s Sonatas are thirty-two, and it is their joint influence which has determined their paradigmatic status.

Not so in the case of the genre “clarinet quintet”. Firstly, the clarinet is a relatively young instrument, even though it builds on the foundations of earlier instruments with simple reed. This allowed even great masters such as Mozart (or Brahms himself!) to be surprised by its possibilities, especially when they encountered genius performers on that instrument. Secondly, chamber music itself, as we intend it today, was a comparatively new phenomenon. Of course, playing together has been the norm for most of music’s history throughout times and places. But the concept of an elevated, artistic music-making, which goes beyond the boundaries of the bourgeois home and of the circle of amateur musicians, is a concept which emerged only gradually, and not without difficulty.

Thus, even though Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet is not the first example of a work for this specific ensemble (i.e. a clarinet and a string quartet), it is certainly the first absolute masterpiece to have been written for it. And it immediately became the unavoidable benchmark and reference point for all other pieces written in this genre. Mozart had been prompted to compose it by his encounter with a genius clarinetist, who had unveiled to him the enormous potential of this instrument. And Mozart made full use of the clarinet and of its genius player’s capabilities, writing a perfect work which remains among the highest creations of its composer.

Approximately a century later (Mozart’s Quintet was composed in 1789), in 1891, another encounter between a genius player and a genius composer would yield another absolute masterpiece. In the meanwhile, several other works had been written for clarinet and string quartet, among them, most notably, a Quintet by Carl Maria von Weber, who had a particular fondness for this instrument. Possibly for this reason, he reserved for the clarinet a soloistic part, which effectively opposes it to the quartet, seen as almost the miniature orchestra for a solo clarinet concerto. By way of contrast, Mozart had created a truly egalitarian milieu, in which all instruments have their share of beauty to play and to offer. Clearly enough, the different timbre of the clarinet stands out with respect to the other instruments, and therefore something like a soloistic approach is unavoidable. But, generally speaking, this masterpiece is a real example of chamber music, whose enchantment results from the cooperation of all involved.

Johannes Brahms was by no means decrepit when he decided that he had had enough of composing. He was still comparatively young, and his creativity was not displaying any signs of waning. However, he had decided that his compositional career was over, and that he would dedicate the remainder of his years to performance, both as a pianist and as a conductor.

However, he had not foreseen the impact that the performance of Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet by Richard Mühlfeld would have meant for him. Mühlfeld was the clarinetist of the Meiningen Hofkapelle, and his playing enthused Brahms to the point that he reconsidered his decision. Brahms wrote about Mühlfeld’s performance to his longtime friend and confidante Clara Schumann, and he soon set to write his own Clarinet Quintet, along with a Clarinet trio (with piano and cello). It should be mentioned that Mühlfeld would also provoke Brahms to compose the two magnificent Clarinet Sonatas op. 120, once more drawing the composer out of another period of artistic silence.

Mühlfeld, indeed, must have been a really exceptional musician, since not only did his music conquer Brahms so powerfully, but it also convinced Joseph Joachim to contravene one of the most rigid rules he had imposed on his concert series in Berlin. Normally, only music for string quartet could be played there; but the impression of Mühlfeld’s playing led Joachim to include this work in the otherwise strings-only series. The piece was tried out by Joachim and his Quartet in a semiprivate context; then, another tryout was undertaken, of an alternative version with a second viola instead of the clarinet. This may puzzle our readers: if the Quintet had been tailored upon Mühlfeld’s gifts, why should one replace the clarinet with a viola? Furthermore, wouldn’t the clarinet part be drowned by the other strings’ thick texture, if not helped to stand out by its different timbre? These are not idle questions, since in fact the version with two violas has rarely been performed. However, that tryout was also exceptional, inasmuch as Joachim himself played the solo viola part, accompanied by the Rose Quartet; that Quartet would be Mühlfeld’s partner in the actual public premiere of the work.

And Brahms’ Quintet was to become in turn a paradigm of the literature for this specific ensemble. Arguably, moreover, we do not owe to Mühlfeld “just” the four masterpieces with clarinet written by Brahms in his last years, but also the other works of that same period. And this is saying something.

When Max Reger decided to write his own Clarinet Quintet, he took Mozart’s Quintet as his model in turn, but, at the same time, he also looked at Brahms’ Quintet as at his second, and more recent, reference point. All three masterpieces have in common the fact of being some of the last fruits of their composers’ creativity: Mozart and Brahms were to outlive the composition of their Quintets by a couple of years, while for Reger this was to be his very last work. Indeed, death caught him before the work’s premiere, which took place posthumously and in memory of its composer. Reger explicitly acknowledged his debt toward Mozart and his music, writing to a publisher that contemporaneous music was lacking “a Mozart”. And the reference to Mozart (and to Brahms) is evident even at the macro level, since all three composers decided to set the last movement of their works as a theme with variations. Reger’s initial project to write one such work did not blossom immediately into a finished piece; this had to wait for a few years, until, in the summer of 1915, he was ready to accept the challenge. Like Brahms, and – again like him – mainly with the purpose in mind to make the score more palatable to the larger public, Reger planned for a version as a string quintet with two violas to be realized; however, he did not live enough to see the work through its whole publication process. The dedicatee of Reger’s work is a further element of continuity with Brahms, since Carl Wendling, an esteemed friend of the composer, had studied with Joseph Joachim and had received the dedication of several other masterpieces by Reger.

Both Quintets seem to mirror a quality which might derive from their composers’ stage of life, but also from the inherent tinge of the clarinet’s sound: i.e. a penchant for meditativeness, for contemplation, for an elegiac reflection on time past, with some regrets perhaps, but also with a touching wisdom and profundity. Moments of levity and grace are certainly not missing, and even hints at humour and at the liveliness and energy of youth; however, they are transfigured by a gaze, as it were, from a distance; by the gaze of composers who were entrusting to the clarinet’s mellow and poetic sound the last words of their artistic activity, and the creative testament of their lives. The appealing quality of these pieces thus resides in their capability to evoke something sublime and enchanting at the same time, and of suggesting a world of musical imagination in which deep reflections on the meaning of life can take place, but always with a smile tinged by melancholia and nostalgia.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads