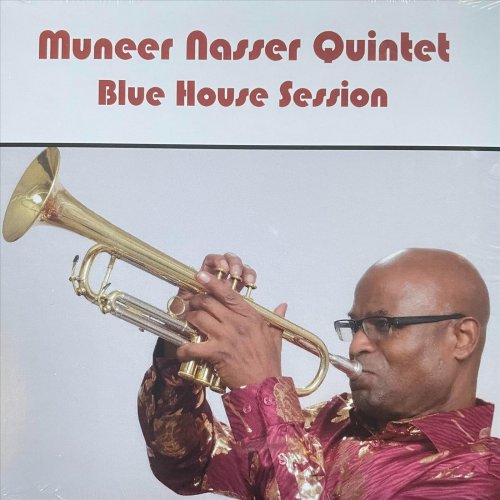

Muneer Nasser - Blue House Session (2024)

BAND/ARTIST: Muneer Nasser

- Title: Blue House Session

- Year Of Release: 2024

- Label: Vertical Visions

- Genre: Post-Bop, Trumpet

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:47:24

- Total Size: 287 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

1 Nasser Blues 8:30

2 Black Disciples 6:19

3 Cancel Culture 7:24

4 All Blues 7:39

5 Polka Dots And Moonbeams 9:44

6 Public Eye 7:48

1 Nasser Blues 8:30

2 Black Disciples 6:19

3 Cancel Culture 7:24

4 All Blues 7:39

5 Polka Dots And Moonbeams 9:44

6 Public Eye 7:48

The best jazz soloist, they say, is one whose solos “tell a story.” Muneer Nasser has more than one story to tell—but they’re not all his own.

Chances are you’ve heard Nasser on trumpet somewhere around town. In just the past two months, he played the D.C. Jazz Festival, Blues Alley, and Westminster Presbyterian Church, all in service of his new album, Blue House Session. His jazz is straighter than straight-ahead: In fact, he’s a little skeptical of straight-ahead jazz (i.e., the mainstream, or what passes for it given jazz’s commercial position) circa 2024.

“I call it catch-me-if-you-can jazz because it kind of starts and kind of rambles on,” he says over lunch in Rockville. “I like the stuff I grew up on, where the groove is emphasized.”

Whether you share his view of contemporary jazz or not, Nasser puts his money where his mouth is. Blue House Session (recorded in the summer of 2023 at the titular studio in Silver Spring) contains some of the purest, most tunefully accessible stuff this side of 1965. There’s blues in spades—oozing out of every corner, not just in the original track “Nasser’s Blues” or the Miles Davis cover “All Blues.” There’s also a wallop of Afro Caribbean sounds, including two Cuban-spiced numbers, “Cancel Culture” and “Public Eye,” and a reggae pastiche in “Black Disciples.”

It almost can’t help but be a killer record, given the band Nasser puts behind him: Tenor saxophonist Elijah Easton, pianist Allyn Johnson, bassist James King, and drummer John Lamkin III all put in their level best. But Nasser himself is a gifted and well-schooled trumpeter. On “Black Disciples” in particular, he pulls out all the technical stops, with pitch bends, lip trills, and growls in his pithy back-and-forth with Easton. He backs the chops up with concise, coherent statements, often thoughtful, always playful—even on the ballad standard “Polka Dots and Moonbeams.” (That last, by the way, is a gem for the flugel, the larger and darker sibling of the trumpet; Nasser is one of many great trumpeters in D.C., but he might be the best flugelhornist, full stop.) Indeed, Blue House Session is one thing that a great deal of contemporary jazz forgets to be: fun.

Now 57, Nasser has been in D.C. for the better part of four decades, arriving as a student at Howard University. He came up through the District’s jazz ranks like a lot of his peers, working at Lawrence Wheatley’s weekly jam sessions at One Step Down and at churches like Anacostia’s Union Temple Baptist. “There was a sense of camaraderie here,” he recalls. “Everybody knew each other. I don’t think enough credit is given to this environment that was created in D.C.” (Swing Beat wholeheartedly agrees with that sentiment.)

But that environment is not Nasser’s foundation. That’s where his other stories come in.

The trumpeter is the son of Jamil Nasser, a bass player from Memphis (born George Joyner) who moved to New York in 1956 and began a prolific and quite visible career. He was an especially popular accompanist for modern jazz pianists, first making his mark with fellow Memphian Phineas Newborn Jr. before working with Red Garland and Thelonious Monk, as well as Ahmad Jamal, with whom he collaborated for most of the 1960s and into the ’70s.

Muneer, one of Jamil’s three sons, is more than just a musician; he’s the author of Upright Bass: The Musical Life and Legacy of Jamil Nasser. Written in the first person, the book is not a conventional biography, or even an autobiography per se: “Dad asked me to write a memoir,” he says in the preface. He based the book on interviews with his father—conducted before Alzheimer’s disease ravaged the elder Nasser’s memory—and his extensive self-collected archive of photos, flyers, and news clippings.

Upright Bass offers a very different perspective on jazz life. Jamil released only one album as a bandleader (in 1961, when he was still George Joyner), otherwise he was known as a sideman. Sidemen don’t usually get a say in the realm of the jazz memoir—which is unfortunate, as Upright Bass demonstrates. Jamil went everywhere the leaders who employed him did (Muneer does some great detective work on his father’s time with Monk, for example), making him not only a star witness to and participant in history, but one who experienced it within the trenches.

Today, Jamil Nasser is generally thought of as a utility player, a sideman with a name but no strong voice of his own. Upright Bass shows that he was anything but: Jamil is a fearsome personality, a principled activist (often isolated even within the Black community of New York and, later, Hempstead, Long Island, because he was a devout Muslim) who demanded respect and self-possession, and someone who was always ready to give support (not just musically) to musicians and others in need. In the 1980s, he defied the anti-apartheid cultural boycott of South Africa, journeying there as a working musician not for the sake of profit, but to gather information firsthand. This was a man with a lot to tell us. And through his son, he does.

This leaves Muneer Nasser juggling two legacies. He has ensured that his father is not a forgotten sideman, while also making a memorable niche in D.C. jazz for himself. “My father’s field of activity transcended playing great bass lines and solos,” Nasser says. “[He was] an educator, jazz advocate, herbalist, record producer, concert organizer, fiction writer [of Big Willie, an unpublished novel about a Black cowboy], actor [Jamil had a small part in the 1996 movie The Preacher’s Wife, among others], and spiritual counselor.” His primary lesson to his son, Nasser adds, was to “live a balanced life, which encompasses creative, intellectual, spiritual, and economic pursuits. Lift as you climb!”

Blue House Session (Nasser’s second album, after 2019’s A Soldier’s Story) will no doubt land him some more gigs in the near future; while you’re there, buy the book.

Chances are you’ve heard Nasser on trumpet somewhere around town. In just the past two months, he played the D.C. Jazz Festival, Blues Alley, and Westminster Presbyterian Church, all in service of his new album, Blue House Session. His jazz is straighter than straight-ahead: In fact, he’s a little skeptical of straight-ahead jazz (i.e., the mainstream, or what passes for it given jazz’s commercial position) circa 2024.

“I call it catch-me-if-you-can jazz because it kind of starts and kind of rambles on,” he says over lunch in Rockville. “I like the stuff I grew up on, where the groove is emphasized.”

Whether you share his view of contemporary jazz or not, Nasser puts his money where his mouth is. Blue House Session (recorded in the summer of 2023 at the titular studio in Silver Spring) contains some of the purest, most tunefully accessible stuff this side of 1965. There’s blues in spades—oozing out of every corner, not just in the original track “Nasser’s Blues” or the Miles Davis cover “All Blues.” There’s also a wallop of Afro Caribbean sounds, including two Cuban-spiced numbers, “Cancel Culture” and “Public Eye,” and a reggae pastiche in “Black Disciples.”

It almost can’t help but be a killer record, given the band Nasser puts behind him: Tenor saxophonist Elijah Easton, pianist Allyn Johnson, bassist James King, and drummer John Lamkin III all put in their level best. But Nasser himself is a gifted and well-schooled trumpeter. On “Black Disciples” in particular, he pulls out all the technical stops, with pitch bends, lip trills, and growls in his pithy back-and-forth with Easton. He backs the chops up with concise, coherent statements, often thoughtful, always playful—even on the ballad standard “Polka Dots and Moonbeams.” (That last, by the way, is a gem for the flugel, the larger and darker sibling of the trumpet; Nasser is one of many great trumpeters in D.C., but he might be the best flugelhornist, full stop.) Indeed, Blue House Session is one thing that a great deal of contemporary jazz forgets to be: fun.

Now 57, Nasser has been in D.C. for the better part of four decades, arriving as a student at Howard University. He came up through the District’s jazz ranks like a lot of his peers, working at Lawrence Wheatley’s weekly jam sessions at One Step Down and at churches like Anacostia’s Union Temple Baptist. “There was a sense of camaraderie here,” he recalls. “Everybody knew each other. I don’t think enough credit is given to this environment that was created in D.C.” (Swing Beat wholeheartedly agrees with that sentiment.)

But that environment is not Nasser’s foundation. That’s where his other stories come in.

The trumpeter is the son of Jamil Nasser, a bass player from Memphis (born George Joyner) who moved to New York in 1956 and began a prolific and quite visible career. He was an especially popular accompanist for modern jazz pianists, first making his mark with fellow Memphian Phineas Newborn Jr. before working with Red Garland and Thelonious Monk, as well as Ahmad Jamal, with whom he collaborated for most of the 1960s and into the ’70s.

Muneer, one of Jamil’s three sons, is more than just a musician; he’s the author of Upright Bass: The Musical Life and Legacy of Jamil Nasser. Written in the first person, the book is not a conventional biography, or even an autobiography per se: “Dad asked me to write a memoir,” he says in the preface. He based the book on interviews with his father—conducted before Alzheimer’s disease ravaged the elder Nasser’s memory—and his extensive self-collected archive of photos, flyers, and news clippings.

Upright Bass offers a very different perspective on jazz life. Jamil released only one album as a bandleader (in 1961, when he was still George Joyner), otherwise he was known as a sideman. Sidemen don’t usually get a say in the realm of the jazz memoir—which is unfortunate, as Upright Bass demonstrates. Jamil went everywhere the leaders who employed him did (Muneer does some great detective work on his father’s time with Monk, for example), making him not only a star witness to and participant in history, but one who experienced it within the trenches.

Today, Jamil Nasser is generally thought of as a utility player, a sideman with a name but no strong voice of his own. Upright Bass shows that he was anything but: Jamil is a fearsome personality, a principled activist (often isolated even within the Black community of New York and, later, Hempstead, Long Island, because he was a devout Muslim) who demanded respect and self-possession, and someone who was always ready to give support (not just musically) to musicians and others in need. In the 1980s, he defied the anti-apartheid cultural boycott of South Africa, journeying there as a working musician not for the sake of profit, but to gather information firsthand. This was a man with a lot to tell us. And through his son, he does.

This leaves Muneer Nasser juggling two legacies. He has ensured that his father is not a forgotten sideman, while also making a memorable niche in D.C. jazz for himself. “My father’s field of activity transcended playing great bass lines and solos,” Nasser says. “[He was] an educator, jazz advocate, herbalist, record producer, concert organizer, fiction writer [of Big Willie, an unpublished novel about a Black cowboy], actor [Jamil had a small part in the 1996 movie The Preacher’s Wife, among others], and spiritual counselor.” His primary lesson to his son, Nasser adds, was to “live a balanced life, which encompasses creative, intellectual, spiritual, and economic pursuits. Lift as you climb!”

Blue House Session (Nasser’s second album, after 2019’s A Soldier’s Story) will no doubt land him some more gigs in the near future; while you’re there, buy the book.

Year 2024 | Jazz | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads