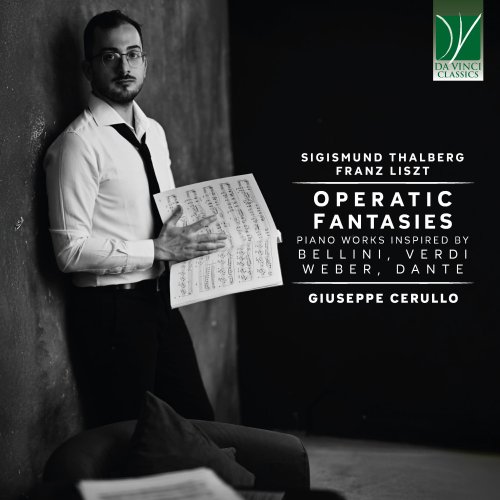

Giuseppe Cerullo - Operatic Fantasies: Piano Works Inspired by Bellini, Verdi, Weber, Dante (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Giuseppe Cerullo

- Title: Operatic Fantasies: Piano Works Inspired by Bellini, Verdi, Weber, Dante

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:16:17

- Total Size: 265 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Quatuor de l´Opéra: I Puritani de Bellini, Op. 70

02. La Traviata, Fantaisie pour piano, Op. 78

03. Grande Fantaisie et Variations sur des motifs de l'Opéra Norma de Bellini, Op. 12

04. Fantaisie sur Norma, Op. 57

05. Fantaisie über Themen aus "Der Freischütz", S.451

06. Après une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi sonata, S.161

Rivalry, normally, is not a pleasant aspect of human living and sociability. We all, rightly, favour peaceable environments and fruitful cooperation. However, there are circumstances in which a fair amount of competitiveness results in general improvements, either in one’s personal life or in that of society as a whole—or in both. To give an example outside the musical world, Siena is unanimously considered one of the most beautiful cities in the world. It is structured into a series of “contrade,” i.e., territorial segments which correspond to social units, where solidarity is extremely high and widespread and a number of positive initiatives take place. These are mainly due to the extreme rivalry among the different “contrade,” whereby each inhabitant of a contrada does his or her best to outdo those of the neighbouring contrada.

Something similar, on the musical plane, happened with Liszt and Thalberg, but other famous rivalries could also be mentioned: Lully and Rameau, or Brahms and Wagner, to cite but a few. Franz Liszt and Sigismund Thalberg were famously opposed by their contemporaries. Indeed, as happened with Brahms and Wagner, it was not the musicians themselves who fiercely opposed each other, but rather their fans, the press, and the patrons. By contrasting them with each other, however, several positive and unexpected results were obtained. One of them was the stimulus to develop some aspects of musical aesthetics, which were provoked by the audience’s appreciation of their distinctive traits as pianists and composers. Another was to encourage them both to outdo the other, and thus to push them constantly forward in their quest for artistic and pianistic perfection. And a final, unintended one, was to promote a cross-fertilization of their respective styles, whereby “Thalbergian” passages are clearly found in Liszt’s works, and vice versa.

The two pianists/composers were very different from each other, but also very similar in other respects. Their backgrounds were very different. Liszt came from a dignified but not particularly well-to-do family (indeed, at some moments of his youth he had to struggle to make ends meet, not least because he liked a certain standard of living). Thalberg’s origins were the object of surmise and dispute in his time and still are. Many believed him to be the illegitimate son of two members of the Austrian high nobility, and his “official” parents to be just a cover-up. Currently, scholars have disputed this; even so, they maintain that aristocratic blood did flow in his veins, and it is certain that he was given every opportunity to study and be profitably introduced into the highest milieus of contemporary society.

Both demonstrated considerable musical talents since their earliest childhood, and both considered other vocational paths besides pianism. Liszt considered the possibility of becoming a priest—he considered it repeatedly and consistently, until, in his later years, he received minor orders and wore a religious habit; Thalberg, instead, was first encouraged to pursue a diplomatic career, and that was what led him first to Vienna.

Seen from this perspective, Liszt would appear to be the more seriously minded of the two, and Thalberg as the lover of “the world.” Whilst we will not be considering the depths of their personality—these are not an object for musicologists to study, even though they frequently indulge in such speculations—objectively it seems that the personality of Liszt was more buoyant, whilst Thalberg was known for his modesty and also for his humility.

Soon, the two pianists came to be seen as each other’s direct and only rival. They may have disliked this, but, at the same time, they also profited from this competition. Not only, indeed, in the ways outlined before, but also because publicity came to both from those praising their rival or denigrating him.

It was difficult, indeed, to establish who was the best. Their respective styles, both in playing and in performing, were very different. Both were amazing virtuosi, who took audiences by storm and astonished them with unheard-of effects. But their virtuosity was not of the same nature. Liszt impressed his listeners with thunderous octaves, powerful passages, brilliant chords; the piano was turned into a symphonic orchestra in his hands. Thalberg was considered more of a poet, even though difficulties abound in his works. He was particularly admired for a unique aspect of his playing, which was at first so innovative that people could not believe their ears. The effect for which Thalberg was best known was that of the “three hands.” He created pianistic textures in which the left hand was assigned the bass line, as is normally the case; the right hand played pearly decorations, such as arpeggios and the like; and a third part was played alternately by both hands. This was conveniently assigned to the central section of the piano keyboard, which was easily accessible by both hands, and it contained the melodic part. The advantages of this setting were that, firstly, the central range of the piano is best suited for cantabile playing; secondly, by a skillful use of the alternating hands and of pedalling, the illusion could be created of a “three-handed” pianist. In Thalberg’s hands, the piano was turned into a chamber music ensemble, or into a voice-piano duet.

Thalberg was better disposed to acknowledge Liszt’s superiority than vice versa. History, indeed, has decreed Liszt to be a greater musician than Thalberg, mainly by virtue of the comparison of their respective compositional outputs. Liszt’s oeuvre is by no means limited to the piano—although piano works constitute a more than substantial part of it—whilst Thalberg’s works for other ensembles or instruments have not conquered a stable place in the concert repertoire. Indeed, a similar fate befell his pianistic output, which has not fallen entirely into oblivion, but is still much less played than it deserves, especially in comparison with Liszt’s.

Not only as performers, but also as piano composers, there are at least some parts of Thalberg’s oeuvre which easily stand comparison with similar works by Liszt. True, Thalberg did not leave anything along the lines of Liszt’s piano masterpiece, the B-minor Sonata. But, when they are compared with each other in works of the same genre, it is much more difficult to assign the palm of victory to either of them. And this is what happens in this Da Vinci Classics CD, which seems to re-enact, today, the legendary piano duel which saw Thalberg and Liszt facing each other directly. The duel took place at the Belgiojoso Palace, on the prompting of the housemistress. The result was far from a clear-cut victory for either of them: the lady who had organized the challenge and who acted as its referee reportedly said that Thalberg was the first pianist in the world, but Liszt was unique. This diplomatic sentence could not be taken as a smashing victory by either of the pianists. However, since that moment, the two started to be on friendly terms, even though their audiences kept opposing them to each other.

The programme recorded here showcases some landmarks of Thalberg’s output, whose best examples, as critics unanimously affirm, are to be found precisely in the domain of operatic fantasies and potpourris. Here, Thalberg’s skill in creating piano textures favouring the singing tone and the melodic lines comes to the fore, as does his capability to evoke the rich fabric of operatic accompaniments. Indeed, it is curious to observe an interesting phenomenon. Robert Schumann, who was one of the most perceptive music critics in history—besides being a compositional genius himself—was by no means a fan of Liszt’s playing, and, in his case, this was certainly not due to envy or jealousy. Schumann was very generous and kind with his colleagues. Still, when considering Thalberg’s works, Schumann praised unconditionally those works written in the style he normally decried, and seemed not to appreciate those closer to his own artistic ideal. When Thalberg wrote polyphonic pieces, making use of complex counterpoint, Schumann criticized his works rather harshly. He instead praised his fantasies on Italian operas, which were normally very far from Schumann’s own artistic sphere. (Interestingly, the Thalberg repertoire recorded here comes mostly from Italian opera, which, indeed, came directly into Thalberg’s household when he married in the operatic world. Liszt’s Fantasia is, instead, based on the masterpiece of the founder of German opera, Weber. Curiously, Thalberg’s very first attempt at operatic fantasies was grounded on Weber’s opera Euryanthe, thus making a fascinating coincidence of opposites. And, of course, Liszt was not averse to paraphrases from Italian operas, as his celebrated Rigoletto Fantasy clearly displays.)

The comparison between Liszt’s and Thalberg’s Fantasies, allowed by the present recording, will enable the listener to formulate his or her own evaluation as to the artistic quality of both pianist-composers. However, the CD also includes one of Liszt’s piano masterpieces, the spectacular Fantasia quasi Sonata “Après une lecture de Dante,” whereby the epic religious poetry of the Italian author is almost translated into sounds, in a very complex piece which anticipates some of the most impressive and revolutionary traits of the B-minor Sonata. Here, one would say, Liszt lays one of his aces on the table. Comparisons here become more unfavourable for Thalberg, and we are left with a feeling of Liszt’s superiority as a composer. Perhaps, as the pianists’ aristocratic judge would say, Thalberg was really the first, but Liszt was unique. Or, possibly, listeners will find another way, one of their own, to express the feelings elicited in them by the direct comparison of these two great, immortal artists whose music remains as a testament to their greatness.

01. Quatuor de l´Opéra: I Puritani de Bellini, Op. 70

02. La Traviata, Fantaisie pour piano, Op. 78

03. Grande Fantaisie et Variations sur des motifs de l'Opéra Norma de Bellini, Op. 12

04. Fantaisie sur Norma, Op. 57

05. Fantaisie über Themen aus "Der Freischütz", S.451

06. Après une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi sonata, S.161

Rivalry, normally, is not a pleasant aspect of human living and sociability. We all, rightly, favour peaceable environments and fruitful cooperation. However, there are circumstances in which a fair amount of competitiveness results in general improvements, either in one’s personal life or in that of society as a whole—or in both. To give an example outside the musical world, Siena is unanimously considered one of the most beautiful cities in the world. It is structured into a series of “contrade,” i.e., territorial segments which correspond to social units, where solidarity is extremely high and widespread and a number of positive initiatives take place. These are mainly due to the extreme rivalry among the different “contrade,” whereby each inhabitant of a contrada does his or her best to outdo those of the neighbouring contrada.

Something similar, on the musical plane, happened with Liszt and Thalberg, but other famous rivalries could also be mentioned: Lully and Rameau, or Brahms and Wagner, to cite but a few. Franz Liszt and Sigismund Thalberg were famously opposed by their contemporaries. Indeed, as happened with Brahms and Wagner, it was not the musicians themselves who fiercely opposed each other, but rather their fans, the press, and the patrons. By contrasting them with each other, however, several positive and unexpected results were obtained. One of them was the stimulus to develop some aspects of musical aesthetics, which were provoked by the audience’s appreciation of their distinctive traits as pianists and composers. Another was to encourage them both to outdo the other, and thus to push them constantly forward in their quest for artistic and pianistic perfection. And a final, unintended one, was to promote a cross-fertilization of their respective styles, whereby “Thalbergian” passages are clearly found in Liszt’s works, and vice versa.

The two pianists/composers were very different from each other, but also very similar in other respects. Their backgrounds were very different. Liszt came from a dignified but not particularly well-to-do family (indeed, at some moments of his youth he had to struggle to make ends meet, not least because he liked a certain standard of living). Thalberg’s origins were the object of surmise and dispute in his time and still are. Many believed him to be the illegitimate son of two members of the Austrian high nobility, and his “official” parents to be just a cover-up. Currently, scholars have disputed this; even so, they maintain that aristocratic blood did flow in his veins, and it is certain that he was given every opportunity to study and be profitably introduced into the highest milieus of contemporary society.

Both demonstrated considerable musical talents since their earliest childhood, and both considered other vocational paths besides pianism. Liszt considered the possibility of becoming a priest—he considered it repeatedly and consistently, until, in his later years, he received minor orders and wore a religious habit; Thalberg, instead, was first encouraged to pursue a diplomatic career, and that was what led him first to Vienna.

Seen from this perspective, Liszt would appear to be the more seriously minded of the two, and Thalberg as the lover of “the world.” Whilst we will not be considering the depths of their personality—these are not an object for musicologists to study, even though they frequently indulge in such speculations—objectively it seems that the personality of Liszt was more buoyant, whilst Thalberg was known for his modesty and also for his humility.

Soon, the two pianists came to be seen as each other’s direct and only rival. They may have disliked this, but, at the same time, they also profited from this competition. Not only, indeed, in the ways outlined before, but also because publicity came to both from those praising their rival or denigrating him.

It was difficult, indeed, to establish who was the best. Their respective styles, both in playing and in performing, were very different. Both were amazing virtuosi, who took audiences by storm and astonished them with unheard-of effects. But their virtuosity was not of the same nature. Liszt impressed his listeners with thunderous octaves, powerful passages, brilliant chords; the piano was turned into a symphonic orchestra in his hands. Thalberg was considered more of a poet, even though difficulties abound in his works. He was particularly admired for a unique aspect of his playing, which was at first so innovative that people could not believe their ears. The effect for which Thalberg was best known was that of the “three hands.” He created pianistic textures in which the left hand was assigned the bass line, as is normally the case; the right hand played pearly decorations, such as arpeggios and the like; and a third part was played alternately by both hands. This was conveniently assigned to the central section of the piano keyboard, which was easily accessible by both hands, and it contained the melodic part. The advantages of this setting were that, firstly, the central range of the piano is best suited for cantabile playing; secondly, by a skillful use of the alternating hands and of pedalling, the illusion could be created of a “three-handed” pianist. In Thalberg’s hands, the piano was turned into a chamber music ensemble, or into a voice-piano duet.

Thalberg was better disposed to acknowledge Liszt’s superiority than vice versa. History, indeed, has decreed Liszt to be a greater musician than Thalberg, mainly by virtue of the comparison of their respective compositional outputs. Liszt’s oeuvre is by no means limited to the piano—although piano works constitute a more than substantial part of it—whilst Thalberg’s works for other ensembles or instruments have not conquered a stable place in the concert repertoire. Indeed, a similar fate befell his pianistic output, which has not fallen entirely into oblivion, but is still much less played than it deserves, especially in comparison with Liszt’s.

Not only as performers, but also as piano composers, there are at least some parts of Thalberg’s oeuvre which easily stand comparison with similar works by Liszt. True, Thalberg did not leave anything along the lines of Liszt’s piano masterpiece, the B-minor Sonata. But, when they are compared with each other in works of the same genre, it is much more difficult to assign the palm of victory to either of them. And this is what happens in this Da Vinci Classics CD, which seems to re-enact, today, the legendary piano duel which saw Thalberg and Liszt facing each other directly. The duel took place at the Belgiojoso Palace, on the prompting of the housemistress. The result was far from a clear-cut victory for either of them: the lady who had organized the challenge and who acted as its referee reportedly said that Thalberg was the first pianist in the world, but Liszt was unique. This diplomatic sentence could not be taken as a smashing victory by either of the pianists. However, since that moment, the two started to be on friendly terms, even though their audiences kept opposing them to each other.

The programme recorded here showcases some landmarks of Thalberg’s output, whose best examples, as critics unanimously affirm, are to be found precisely in the domain of operatic fantasies and potpourris. Here, Thalberg’s skill in creating piano textures favouring the singing tone and the melodic lines comes to the fore, as does his capability to evoke the rich fabric of operatic accompaniments. Indeed, it is curious to observe an interesting phenomenon. Robert Schumann, who was one of the most perceptive music critics in history—besides being a compositional genius himself—was by no means a fan of Liszt’s playing, and, in his case, this was certainly not due to envy or jealousy. Schumann was very generous and kind with his colleagues. Still, when considering Thalberg’s works, Schumann praised unconditionally those works written in the style he normally decried, and seemed not to appreciate those closer to his own artistic ideal. When Thalberg wrote polyphonic pieces, making use of complex counterpoint, Schumann criticized his works rather harshly. He instead praised his fantasies on Italian operas, which were normally very far from Schumann’s own artistic sphere. (Interestingly, the Thalberg repertoire recorded here comes mostly from Italian opera, which, indeed, came directly into Thalberg’s household when he married in the operatic world. Liszt’s Fantasia is, instead, based on the masterpiece of the founder of German opera, Weber. Curiously, Thalberg’s very first attempt at operatic fantasies was grounded on Weber’s opera Euryanthe, thus making a fascinating coincidence of opposites. And, of course, Liszt was not averse to paraphrases from Italian operas, as his celebrated Rigoletto Fantasy clearly displays.)

The comparison between Liszt’s and Thalberg’s Fantasies, allowed by the present recording, will enable the listener to formulate his or her own evaluation as to the artistic quality of both pianist-composers. However, the CD also includes one of Liszt’s piano masterpieces, the spectacular Fantasia quasi Sonata “Après une lecture de Dante,” whereby the epic religious poetry of the Italian author is almost translated into sounds, in a very complex piece which anticipates some of the most impressive and revolutionary traits of the B-minor Sonata. Here, one would say, Liszt lays one of his aces on the table. Comparisons here become more unfavourable for Thalberg, and we are left with a feeling of Liszt’s superiority as a composer. Perhaps, as the pianists’ aristocratic judge would say, Thalberg was really the first, but Liszt was unique. Or, possibly, listeners will find another way, one of their own, to express the feelings elicited in them by the direct comparison of these two great, immortal artists whose music remains as a testament to their greatness.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads