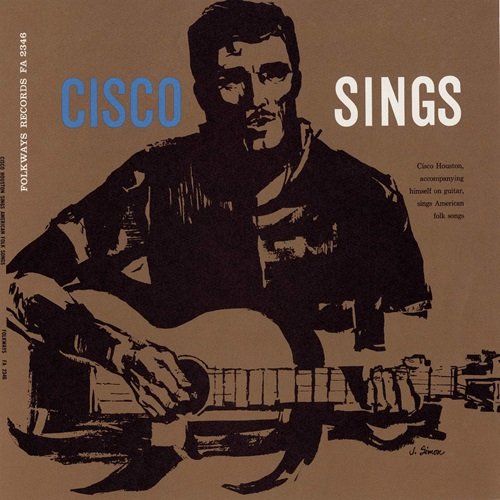

Cisco Houston is best remembered as a traveling companion and harmony vocalist for Woody Guthrie. But Houston was equally influential as a folksinger in his own right. With his acoustic guitar accompanying his unadorned baritone vocals, Houston provided a musical voice for America's downtrodden -- the cowboys, miners, union activists, railroad workers, and hobos -- that resonated in the songs of the urban folk revival of the 1950s and '60s.

The second of four children, Houston inherited the musical traditions of North Carolina from his father, a sheet metal worker, and the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia, where his mother and grandmother learned many traditional folk songs. A native of Delaware, Houston moved, at the age of two, to Southern California with his family. Nearly blind and suffering from nystagmus, Houston's early interests were in theater and art. At Rockdale Elementary School, in the Eagle Rock Valley between Pasadena and Glendale, he participated in many school productions. He sharpened his acting skills with courses at L.A. City College and in productions presented by Hollywood Theater groups and the Pasadena Playhouse.

Deserted by his father in 1932, two years after moving with his family to Bakersfield, Houston left home at the age of 16, and together with a brother wandered the country seeking work. The journey marked the first of more than 30 treks across the United States. During the trip, Houston renamed himself after Cisco, CA, a small town between Sacramento and Reno, NV.

Returning to Hollywood, Houston renewed his involvement with theater groups. In one such group, he met and befriended actor Will Geer. In 1938, Houston and Geer heard a radio show on KFVD in Hollywood featuring Woody Guthrie. Inspired by Guthrie's performance, the two, struggling, decided to visit the young folksinger. When they did, it sparked a longtime friendship. Not long after meeting Guthrie, Houston began appearing on the radio show, singing tenor harmonies to Guthrie's lead vocals. Houston and Guthrie subsequently began performing at migrant camps, occasionally with Burl Ives, with Geer paying their expenses. When Guthrie traveled to New York in 1939, he persuaded Houston to join him. Houston later returned to the Big Apple on his own and accepted a job as a street barker for a burlesque house on 42nd Street.

In 1940, Houston joined the merchant marines. Although he spent most of the next few years on a ship, he performed with Guthrie and the Almanac Singers whenever the opportunity arose. Shortly after the start of World War II, Guthrie joined him on the seas. During the time they served together, the two folksingers were on two ships that were torpedoed. After his discharge, Houston traveled in and out of New York, often staying with folksinger Leadbelly and his wife, Martha. Houston continued to spend much of his time on the road, working occasionally as a cowboy, lumberjack, and potato picker, and appearing in bit roles in movies.

After Guthrie signed a recording contract with Folkways, Houston sang high-tenor vocals on his recordings. He also made his debut solo recordings for the label. In 1948, Houston appeared in the hit Broadway musical The Cradle Will Rock. He returned to Hollywood the following year, however, and appeared in bit roles in several films. By 1950, he was back on the road, traveling with Guthrie.

In the early '50s, Houston recorded several tunes for the Decca label, including several that went unreleased until more recent years. He also appeared on television shows in Tucson, AZ. Houston's greatest break arrived when he was hired to host his own three-days-a-week television show, The Gil Houston Show, for the International Network. By January 1955, the show was broadcast over 550 stations by the Mutual Broadcasting System. He also had his first success as a songwriter when his tune "Crazy Heart," co-written with Lewis Allen, became a minor hit for Jackie Paris.

Things began to fall apart, however, during the red-baiting days of the McCarthy era. Although there is no documentation to show that Houston's radio show was canceled due to a blacklist, the network tired of his leftist views and gave him his walking papers. Houston returned to California to play concerts.

In 1959, Houston was invited, along with Marilyn Child, Sonny Terry, and Brownie McGhee, to perform during a 12-week tour of India, sponsored by the Indo-American Society and the United States Information Service. After his return to the U.S., Houston served as narrator and performer of a CBS-TV show, Folk Sound, U.S.A. Broadcast on June 16, 1960, the show represented the first full-length television show on folk music. Later that summer, Houston appeared at the Newport Folk Festival and recorded for the Vanguard label.

Just when it seemed that Houston's career was taking off, he was diagnosed with cancer. His death in the spring of 1961 was mourned throughout the folk community, and memorials were written and recorded by Tom Paxton ("Fare Thee Well, Cisco"), Peter LaFarge ("Cisco Houston Passed This Way"), and Tom McGrath ("Blues for Cisco Houston").

In 1965, Moses Asch, the owner of Folkways Records, and Irwin Silber, publisher of Sing Out! magazine, edited a collection of Houston's songs, 900 Miles and Other Railroad Ballads, published by Oak Publications.