Tracklist:

1. Opern-Revue, Op. 8: La Traviata, No. 29 (11:25)

2. Opern-Revue, Op. 8: Il Trovatore, No. 27 (11:23)

3. Opern-Revue, Op. 8: Rigoletto, No. 21 (11:55)

4. Opern-Revue, Op. 8: Die sizilianische vesper, No. 31 (12:11)

5. Opern-Revue, Op. 8: Ernani, No. 14 (13:31)

6. Opern-Revue, Op. 8: Nabucodonosor, No. 22 (12:52)

In today’s popular culture, as represented, for instance, in rock and pop music, the guitar is essentially a harmonic instrument. Most amateur guitar players are “strummers”, since the rudiments of chord-playing on the guitar are very easy to learn, and allow the budding guitarist to accompany singing passably within a very short period of training. However, to the other end of the spectrum of guitar playing, this is an instrument capable of great refinement. Well beyond the boundaries of harmonic playing, the guitar is capable of polyphony (i.e. the simultaneous performance of more than one melody), as well as of accompanied melodies. Proficient and professional guitar players can make their instrument “sing”, and they can play, at the same time, a tune and its accompaniment; therefore, the guitar partakes in the fate of an elite of instruments (such as the keyboards) which are entirely autonomous and self-standing, even though they profitably interact with other instruments in symphonic and chamber music.

Still, this kind of playing is doubtlessly challenging. At the basic level, it requires independence of the fingers and coordination of the hands. But, at a higher level, it implies the capability of creating different shades and nuances; of differentiating the various layers of music so as to allow the listener to grasp its true complexity. The real benchmark of a true virtuoso guitarist, therefore, is possibly not the ability to play complex and quick passagework, but, even more than that, the skill to render satisfactorily both the melodic, singing quality of a line, and its accompaniment. When, furthermore, this accompaniment derives from an original symphonic score, not only should the guitar evoke the human voice with its singing melodies, but it ought also to paint the accompaniment in a wide palette of colours, creating the illusion of an orchestral texture.

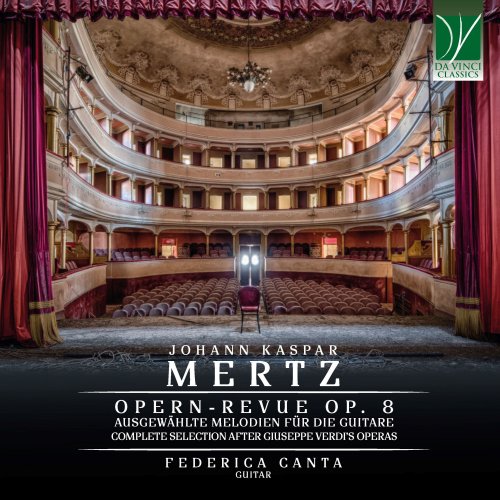

It comes therefore as no wonder that such a virtuoso guitarist as Mertz created no less than 38 “opera revues” as those recorded in this Da Vinci Classics production. These are long fantasies, some of which are extremely demanding, in which Mertz offers the listener a “review”, in a manner of speaking, of an entire famous opera of his times.

Mertz had the unluck of living through one of the “holes” in the history of guitar playing. His life coincided with the Romantic era, whose aesthetics tended to pursue the sublime, majestic, grandioso. The size of the concert halls augmented constantly, and the ideal of sound was that of the symphonic orchestra, whose components tended in turn to increase in number.

The guitar was much more popular, generally speaking, before and after his lifetime; still, it is noteworthy that he managed to achieve considerable success even within a less than optimal cultural context.

In that context, opera was central in many European countries. In Italy, opera was the undisputed protagonist of musical life; not only did it absorb most resources available for music, in terms of economy but also of interest and involvement. It also infiltrated what was left of purely instrumental music, since a substantial portion of Italian instrumental music, in the nineteenth century, was intensely influenced by opera.

This is observed in the “opera revues” recorded here, written in Austria but inspired by Italian culture, and in which Mertz accepts the challenge of creating guitar pieces out of material originally conceived for voice and orchestra. The patchwork he realizes by weaving together many musical ideas excerpted from some of the most famous operas of the day is held together by passages whose virtuosity is openly declared.

The choice of operas made by the composer provides players with an extended repertoire of possibilities, out of which six operas by Verdi were selected for this CD. The first three performed here are written after the three operas commonly known as the “popular trilogy” in Italy. If most of Verdi’s operas were extremely well-known at their times, and are still performed often and widely appreciated, these three are so popular even nowadays that at least a few tunes from each of them are known even by those who have never set foot in an operatic theatre.

Tunes such as Libiamo from Traviata, Di quella pira from Trovatore and La donna è mobile from Rigoletto are effectively part of popular culture, and have earned a place among the all-time immortal tunes. But this can also be said of Va’ pensiero from Nabucodonosor, as will be shortly recounted.

La Traviata has a plot excerpted from a Dumas’ novel, La dame aux camélias. Violetta Valéry is a fascinating but rather dissolute Parisian woman, who is sought after by numerous gentlemen and refuses to commit her heart to any of them. Sempre libera, “always free”, she proclaims initially: her creed seems to be that of free love. Things change upon her meeting with Alfredo Germont, a young man from a “good family”, who falls in love with her and is reciprocated. This seems to be Violetta’s opportunity to change life and to commit herself to faithful love, to marriage and to family life. However, Alfredo’s father is worried by the damage that his son’s acquaintance with Violetta may bring upon the reputation of his other child, a very pure and chaste daughter (Pura siccome un angelo). After having tried to dissuade Alfredo himself (Di Provenza il mar, il suol), he asks Violetta directly to renounce her love for Alfredo in order not to stain his daughter’s purity “by proxy”. Out of love for Alfredo and for his dear ones, Violetta accepts to withdraw from this relationship, even though this will not only estrange Alfredo, but also make him believe that he has been cheated as all others before him. Alfredo grossly insults Violetta, who is also fatally ill with tuberculosis. The couple’s dreams of a rosy future (Parigi, o cara) are shattered by Violetta’s illness (Addio del passato), and her death closes the opera on a heart-rending tone.

The plot of Il Trovatore is virtually impossible to summarize, since it is a frankly contorted and twisted game of concealed identities, misunderstandings, and also bloody vendettas. There are unexpected revelations, very implausible turns such as a mother burning her own child instead of that of her rival, gory killings, tortures, and, of course, the theme of sacrificial love. A touch of picturesqueness is given by the gipsy setting, which is at times very colourfully evoked by Verdi (e.g. with Chi del gitano); all in all, the inconsistencies and absurdities of the libretto are vastly redeemed by Verdi’s immortal music.

A much more convincing story is that of Rigoletto, a hunchback who is the buffoon at the court of the Duke of Mantua, a despicable nobleman. Rigoletto is a very touching figure. As much as he is unfortunate with his physical appearance and his handicap, he is a good and generous father, whose only consolation is his beautiful and pure daughter, Gilda. The Duke’s perfidious behaviour with Gilda is the pivot around which the entire story unfolds, and all listeners are led to sympathise deeply with the sad story of the hunchback. Among the opera’s memorable moments is the celebrated Quartet, which has rightfully earned pride of place in the vocal repertoire, but also has been the object of countless transcriptions.

The Middle-Age story of the Sicilian Vespers provided Verdi and his librettist with the opportunity for setting into music an exceedingly inflammatory plot. The role played by Verdi and his operas in the process known as the Italian Risorgimento – i.e. the upheavals and wars leading to the constitution of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 and its eventual expansions to include zones which belonged in the Austro-Hungarian Empire – is well known and documented. Some of Verdi’s operas had a particularly impactful effect; and I vespri siciliani, along with Nabucco or I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata were among the most controversial. This was so extreme that I vespri siciliani had to appear “in disguise”, so to say, in its first performances in the Italian Peninsula, and its original version was played only in France. Here too the plot is rather complicated to summarize; suffice it to say that a traditional love story intertwines with the rebellion of the Sicilian people against the invader; matters of honour, of loyalty, and of faithfulness make the story a true allegory of what the patriots felt at Verdi’s time.

Another very patriotic piece is found in Ernani, which is in turn a highly political opera. Si ridesti il Leon di Castiglia was in fact another choral movement which elicited the most powerful passions among contemporaneous listeners. Here too the usual themes of honorability, self-sacrifice, love and fight against oppressive powers are rehearsed, with Verdi’s justly prized capability to turn what could become a morality play into a passionate story.

Finally, Nabucodonosor (commonly shortened as Nabucco) is the fascinating and touching story of the Israeli people in their Babylonian captivity. Their longing for their Promised Land, and their impossibility to voice their sacred songs in a foreign land – as expressed beautifully in one of the Biblical Psalms – becomes another song yearning for the independence and freedom of Italy. Va’, pensiero has therefore been adopted as a political song not only by Verdi’s contemporaries, but also by other categories of Italians who felt oppressed and mistreated. From the Istrian exiles after World War Two, to the sympathisers and members of a political party advocating – paradoxically – the division of the Italian nation whose unification Verdi had promoted, Va’, pensiero has become another landmark of Italian culture in the centuries.

The opportunity of listening to many of these magnificent and beautiful tunes played on the guitar is a welcome possibility offered by Mertz’s masterful works and by his extraordinary ability both as a player and as a composer of unforgettable guitar music. An opportunity demonstrating the numerous timbral resources of the guitar.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2024