Quintetto Sinestesia - Ligeti, Françaix, Hindemith: 20th Century Music for Wind Quintet (2024)

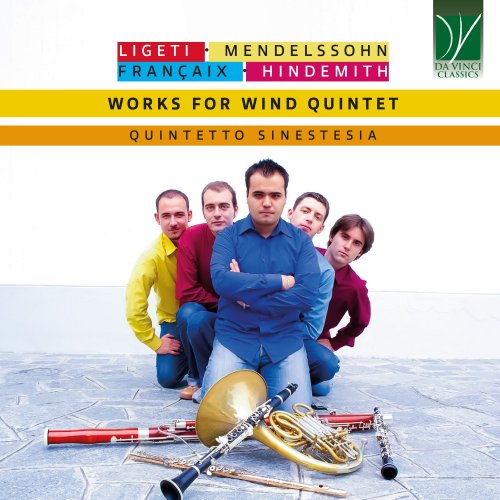

BAND/ARTIST: Quintetto Sinestesia

- Title: Ligeti, Françaix, Hindemith: 20th Century Music for Wind Quintet

- Year Of Release: 2024

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:55:43

- Total Size: 222 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 1, Allegro con spirito

02. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 2, Rubato. Lamentoso

03. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 3, Allegro grazioso

04. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 4, Presto ruvido

05. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 5, Adagio. Mesto

06. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 6, Molto vivace. Capriccioso

07. Die Hebriden (Transcription by Fabrizio Villa)

08. Quintette No. 1: No. 1, Andante tranquillo – Allegro assai

09. Quintette No. 1: No. 2, Presto

10. Quintette No. 1: No. 3, Tema e variazioni

11. Quintette No. 1: No. 4, Tempo di marcia francese

12. Kleine Kammermusik: No. 1, Lustig. Mäßig schnelle Viertel

13. Kleine Kammermusik: No. 2, Walzer. Durchweg sehr leise

14. Kleine Kammermusik: No. 3, Ruhig und einfach. Achtel

15. Kleine Kammermusik: No. 4, Schnelle Viertel

16. Kleine Kammermusik: No. 5, Sehr lebhaft

Not by chance, several terms which concern the world of music begin with syn- or sym-. This is the particle which, in ancient Greek, denoted unity, something shared (like the English word “with”, or the Latin particle co-, as in coworking, cooperating etc.). There is symphony, from the Greek symphonia, “sounding together”. There is syntony, again from the Greek, implying “to have the same tone”; or symbol (music is a symbolic language), from symbolon, “keeping together” – suggesting music’s capability to hold in one hand the various dimensions of the human being.

And then, there is synesthesia. Literally, the Greek word behind it means “to perceive together”. In literature, this word denotes a figure of speech consisting in the juxtaposition of adjectives and nouns pertaining to different sensorial planes. Two Italian poets employed it memorably: Giovanni Pascoli wrote of “voices of blue darkness”, and Eugenio Montale of “cold lights”. In the English-speaking world, Francis Thompson wrote: “I see the crimson blaring of they shawms!”; Keats spoke of the “smoothest silence”, bringing together tactile with auditory feelings; and Robert Penn Warren described “the scream / of the reddening bud of the oak tree”.

This word is also employed in the psychological domain, where it denotes a phenomenon which may verge on the pathological: in its serious form, it implies a confusion of the sensorial planes, so that a person will understand, for instance, an auditory stimulus as a visual one and vice-versa. (This may also be a fascinating experience, when it does not impinge on a person’s autonomy. For instance, Olivier Messiaen allegedly perceived colours when he heard notes, and his scores are frequently enriched by suggestions of visual imagery. One of his former students recounted that he used to ask for “more mauve” or “less blue” when they played for him).

The wind quintet performing in this Da Vinci Classics CD has therefore chosen this word, in its Italian form (“sinestesia”), as their collective name. As they write, this choice was not made by chance: “To perceive together: which art form can evoke, on a par with music, a palette of colours, images, tactile feelings, flavours even; which art form, more than the art of sounds, is capable of merging the five senses into a single perception?”. Furthermore, the “symphony” of our five senses seems to fascinatingly correspond to that of a wind quintet: just as the human body interacts with the outside world in a variety of ways, so do the five instruments featured here (the flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon and French horn) interact with each other. Indeed, playing together perforce implies “feeling” together. Of course, the musicians of a chamber ensemble must listen with the utmost attention to each other, and thus their “co-listening” must be perfect. Frequently, they also have to breathe together: if this applies also to stringed instruments, it is all the more important for winds. And, on the metaphysical plane, they have to “feel” the music together. While the importance of each individual personality is certainly not denied or diminished, it is also fundamental that the interpretive view is shared; that music is felt in a similar fashion by all, so that all may render it, transmit it, offer it to the audience in a consistent fashion. And this is certainly something the members of Sinestesia practise and live constantly.

This shared feeling does not involve the “how” of playing together, but also the “what”. Their repertoire is chosen collaboratively, and involves the exploration of the traditional heritage of this specific ensemble, but also that of lesser-known paths, and the creation of new works, for instance through the art of transcription. As the members of Sinestesia say, “Initially, we were oriented toward the study of the original repertoire for wind quintet. But we also aimed at increasing it, also through the introduction of transcriptions after the orchestral repertoire. The wind quintet has a ‘symphonic’ vocation, and it possesses a wide range of colours. This allows to transfer onto the five pentagrams the fullness of an orchestral score. This is the concept underlying Sinestesia’s project to draw from the masterpieces of symphonic music in order to complete the quintet’s original repertoire, which is disproportionately determined by twentieth-century music. We therefore chose works from the classical-romantic, and even from the Baroque era: this project began with our transcription of Mendelssohn’s Hebrides and Vivaldi’s Four Seasons”.

Felix Mendelssohn was in his late teens when he visited Scotland, taking a boat trip to the Hebrides. It impressed him enormously, for the beauty of the scenery, for the quantity of aural stimuli (here again we have some synesthesia!), but also for the suggestions which the Romantics felt when approaching the Hebrides. Their landscape was certainly very much in keeping with the Romantic taste for nature and for its most extreme, “uncultivated” phenomena, but also with their interest in the supernatural. This had been elicited by the publication, and high dissemination, of Fingal’s poems. Even though they later proved to be a modern forgery, their fascination and the suggestion they provided could not be uprooted, and they formed a part of Romanticism’s shared culture.

Mendelssohn sought a purposefully “primitive” musical language; he wanted his music to mirror the unsophisticated, primeval natural beauty of what he had seen. Revising this magnificent concert Overture some years later, he would write to his sister and confident Fanny: “I still do not consider it finished. The middle part, forte in D major, is very stupid, and savours more of counterpoint than of oil [ie engine oil in the steamers in which he travelled] and seagulls and dead fish, and it ought to be the very reverse”. In the end, he managed to create such a piece, and it is rightfully considered as one of the pillars of the Romantic symphonic repertoire.

If Mendelssohn excelled in self-criticism, György Ligeti was no less ascetic in the self-imposed limits he set for himself. The Six Bagatelles recorded here are, in turn, a transcription (albeit the composer’s, in this case) after six of the twelve pieces which originally constituted Ligeti’s Musica ricercata for piano. Written between 1951 and 1953, and transcribed in 1953, Musica ricercata is founded on a very provocative challenge. For the first piece, the composer allowed himself to use just a single pitch, albeit in whatever position he found that note on the piano’s keyboard. Two notes could be used for the second piece, three for the third, up to the twelfth piece, where all 12 semitones ought to be employed, and which Ligeti construes as a hyper-chromatic Fugue on the model of Girolamo Frescobaldi.

The idea of transcribing a half of this collection for wind quintet is brilliant, since Ligeti’s original works are very much suited to the specific articulation of the winds. Due to the limitations chosen by Ligeti, the texture is frequently pointillistic, and the result is often reminiscent (or rather suggestive) of minimalist music. The influence of Béla Bartók, Ligeti’s fellow citizen, is clearly discernible, especially in the concept of the piano as a percussion instrument – a concept which is translated into a “percussion-like” view of the wind ensemble.

The year after Ligeti’s transcription of Musica ricercata, i.e. 1954, the premiere of Jean Françaix’ Quintette à vent no. 1 took place. The piece had been written six years earlier, in 1948. It was a commission of the Wind Quintet of the National Orchestra of the French Radio TV, and that ensemble was in charge of the premiere. Of its four movements, the first opens with a relatively slow introduction, whose protagonist is the French horn (a homage to the hornist who had actually commissioned the piece!), followed by a virtuosic, brilliant Allegro. The same vivacity and liveliness also characterizes the Scherzo, a sparkling Presto. The most intriguing movement is possibly the Theme with variations, masterfully built on some essential musical ideas. The concluding movement is a firework of ideas, and, once more, its final remarks are allotted to the French horn.

Françaix is unashamed of his ironic and enthralling vein. If most musical and artistic expressions of the post-War era were depressingly sad and desperate, Françaix had no problem whatsoever in bringing a smile on the lips of his listeners.

With Hindemith’s Kammermusik we are brought back to the roaring Twenties (1922), and to an entirely different atmosphere. Just as Françaix (with his quintessentially French family name and his equally French, champagne-like, verve) expresses a very Gallic approach to music, so does Hindemith bring to fulfillment the German view of music. Here, the model openly accepted by the composer is that of Johann Sebastian Bach and of his six Brandenburg Concertos, where the sounds of the Baroque orchestra and the typical traits of its various sections are painstakingly and beautifully explored. Similarly, Hindemith wished to study the colours of contemporaneous music, and to pay homage to the limpid and complex structures of Baroque counterpoint. This particular piece, the second in this series of “serenades”, is almost the embodiment of the objectivist approach to music. It opens with a kind of musical “amuse-bouche”, a divertissement on contrapuntal structures, followed by a grotesque Valse where the shadow of Stravinsky looms large. The slow movement is the musical centre of this composition, whilst the two remaining movements are full of contrasting episodes.

Together, the compositions featured in this album reveal the fecundity and the musical richness of this particular ensemble, and how it can suggest the timbral variety of a full orchestra.

01. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 1, Allegro con spirito

02. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 2, Rubato. Lamentoso

03. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 3, Allegro grazioso

04. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 4, Presto ruvido

05. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 5, Adagio. Mesto

06. Sechs Bagatellen: No. 6, Molto vivace. Capriccioso

07. Die Hebriden (Transcription by Fabrizio Villa)

08. Quintette No. 1: No. 1, Andante tranquillo – Allegro assai

09. Quintette No. 1: No. 2, Presto

10. Quintette No. 1: No. 3, Tema e variazioni

11. Quintette No. 1: No. 4, Tempo di marcia francese

12. Kleine Kammermusik: No. 1, Lustig. Mäßig schnelle Viertel

13. Kleine Kammermusik: No. 2, Walzer. Durchweg sehr leise

14. Kleine Kammermusik: No. 3, Ruhig und einfach. Achtel

15. Kleine Kammermusik: No. 4, Schnelle Viertel

16. Kleine Kammermusik: No. 5, Sehr lebhaft

Not by chance, several terms which concern the world of music begin with syn- or sym-. This is the particle which, in ancient Greek, denoted unity, something shared (like the English word “with”, or the Latin particle co-, as in coworking, cooperating etc.). There is symphony, from the Greek symphonia, “sounding together”. There is syntony, again from the Greek, implying “to have the same tone”; or symbol (music is a symbolic language), from symbolon, “keeping together” – suggesting music’s capability to hold in one hand the various dimensions of the human being.

And then, there is synesthesia. Literally, the Greek word behind it means “to perceive together”. In literature, this word denotes a figure of speech consisting in the juxtaposition of adjectives and nouns pertaining to different sensorial planes. Two Italian poets employed it memorably: Giovanni Pascoli wrote of “voices of blue darkness”, and Eugenio Montale of “cold lights”. In the English-speaking world, Francis Thompson wrote: “I see the crimson blaring of they shawms!”; Keats spoke of the “smoothest silence”, bringing together tactile with auditory feelings; and Robert Penn Warren described “the scream / of the reddening bud of the oak tree”.

This word is also employed in the psychological domain, where it denotes a phenomenon which may verge on the pathological: in its serious form, it implies a confusion of the sensorial planes, so that a person will understand, for instance, an auditory stimulus as a visual one and vice-versa. (This may also be a fascinating experience, when it does not impinge on a person’s autonomy. For instance, Olivier Messiaen allegedly perceived colours when he heard notes, and his scores are frequently enriched by suggestions of visual imagery. One of his former students recounted that he used to ask for “more mauve” or “less blue” when they played for him).

The wind quintet performing in this Da Vinci Classics CD has therefore chosen this word, in its Italian form (“sinestesia”), as their collective name. As they write, this choice was not made by chance: “To perceive together: which art form can evoke, on a par with music, a palette of colours, images, tactile feelings, flavours even; which art form, more than the art of sounds, is capable of merging the five senses into a single perception?”. Furthermore, the “symphony” of our five senses seems to fascinatingly correspond to that of a wind quintet: just as the human body interacts with the outside world in a variety of ways, so do the five instruments featured here (the flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon and French horn) interact with each other. Indeed, playing together perforce implies “feeling” together. Of course, the musicians of a chamber ensemble must listen with the utmost attention to each other, and thus their “co-listening” must be perfect. Frequently, they also have to breathe together: if this applies also to stringed instruments, it is all the more important for winds. And, on the metaphysical plane, they have to “feel” the music together. While the importance of each individual personality is certainly not denied or diminished, it is also fundamental that the interpretive view is shared; that music is felt in a similar fashion by all, so that all may render it, transmit it, offer it to the audience in a consistent fashion. And this is certainly something the members of Sinestesia practise and live constantly.

This shared feeling does not involve the “how” of playing together, but also the “what”. Their repertoire is chosen collaboratively, and involves the exploration of the traditional heritage of this specific ensemble, but also that of lesser-known paths, and the creation of new works, for instance through the art of transcription. As the members of Sinestesia say, “Initially, we were oriented toward the study of the original repertoire for wind quintet. But we also aimed at increasing it, also through the introduction of transcriptions after the orchestral repertoire. The wind quintet has a ‘symphonic’ vocation, and it possesses a wide range of colours. This allows to transfer onto the five pentagrams the fullness of an orchestral score. This is the concept underlying Sinestesia’s project to draw from the masterpieces of symphonic music in order to complete the quintet’s original repertoire, which is disproportionately determined by twentieth-century music. We therefore chose works from the classical-romantic, and even from the Baroque era: this project began with our transcription of Mendelssohn’s Hebrides and Vivaldi’s Four Seasons”.

Felix Mendelssohn was in his late teens when he visited Scotland, taking a boat trip to the Hebrides. It impressed him enormously, for the beauty of the scenery, for the quantity of aural stimuli (here again we have some synesthesia!), but also for the suggestions which the Romantics felt when approaching the Hebrides. Their landscape was certainly very much in keeping with the Romantic taste for nature and for its most extreme, “uncultivated” phenomena, but also with their interest in the supernatural. This had been elicited by the publication, and high dissemination, of Fingal’s poems. Even though they later proved to be a modern forgery, their fascination and the suggestion they provided could not be uprooted, and they formed a part of Romanticism’s shared culture.

Mendelssohn sought a purposefully “primitive” musical language; he wanted his music to mirror the unsophisticated, primeval natural beauty of what he had seen. Revising this magnificent concert Overture some years later, he would write to his sister and confident Fanny: “I still do not consider it finished. The middle part, forte in D major, is very stupid, and savours more of counterpoint than of oil [ie engine oil in the steamers in which he travelled] and seagulls and dead fish, and it ought to be the very reverse”. In the end, he managed to create such a piece, and it is rightfully considered as one of the pillars of the Romantic symphonic repertoire.

If Mendelssohn excelled in self-criticism, György Ligeti was no less ascetic in the self-imposed limits he set for himself. The Six Bagatelles recorded here are, in turn, a transcription (albeit the composer’s, in this case) after six of the twelve pieces which originally constituted Ligeti’s Musica ricercata for piano. Written between 1951 and 1953, and transcribed in 1953, Musica ricercata is founded on a very provocative challenge. For the first piece, the composer allowed himself to use just a single pitch, albeit in whatever position he found that note on the piano’s keyboard. Two notes could be used for the second piece, three for the third, up to the twelfth piece, where all 12 semitones ought to be employed, and which Ligeti construes as a hyper-chromatic Fugue on the model of Girolamo Frescobaldi.

The idea of transcribing a half of this collection for wind quintet is brilliant, since Ligeti’s original works are very much suited to the specific articulation of the winds. Due to the limitations chosen by Ligeti, the texture is frequently pointillistic, and the result is often reminiscent (or rather suggestive) of minimalist music. The influence of Béla Bartók, Ligeti’s fellow citizen, is clearly discernible, especially in the concept of the piano as a percussion instrument – a concept which is translated into a “percussion-like” view of the wind ensemble.

The year after Ligeti’s transcription of Musica ricercata, i.e. 1954, the premiere of Jean Françaix’ Quintette à vent no. 1 took place. The piece had been written six years earlier, in 1948. It was a commission of the Wind Quintet of the National Orchestra of the French Radio TV, and that ensemble was in charge of the premiere. Of its four movements, the first opens with a relatively slow introduction, whose protagonist is the French horn (a homage to the hornist who had actually commissioned the piece!), followed by a virtuosic, brilliant Allegro. The same vivacity and liveliness also characterizes the Scherzo, a sparkling Presto. The most intriguing movement is possibly the Theme with variations, masterfully built on some essential musical ideas. The concluding movement is a firework of ideas, and, once more, its final remarks are allotted to the French horn.

Françaix is unashamed of his ironic and enthralling vein. If most musical and artistic expressions of the post-War era were depressingly sad and desperate, Françaix had no problem whatsoever in bringing a smile on the lips of his listeners.

With Hindemith’s Kammermusik we are brought back to the roaring Twenties (1922), and to an entirely different atmosphere. Just as Françaix (with his quintessentially French family name and his equally French, champagne-like, verve) expresses a very Gallic approach to music, so does Hindemith bring to fulfillment the German view of music. Here, the model openly accepted by the composer is that of Johann Sebastian Bach and of his six Brandenburg Concertos, where the sounds of the Baroque orchestra and the typical traits of its various sections are painstakingly and beautifully explored. Similarly, Hindemith wished to study the colours of contemporaneous music, and to pay homage to the limpid and complex structures of Baroque counterpoint. This particular piece, the second in this series of “serenades”, is almost the embodiment of the objectivist approach to music. It opens with a kind of musical “amuse-bouche”, a divertissement on contrapuntal structures, followed by a grotesque Valse where the shadow of Stravinsky looms large. The slow movement is the musical centre of this composition, whilst the two remaining movements are full of contrasting episodes.

Together, the compositions featured in this album reveal the fecundity and the musical richness of this particular ensemble, and how it can suggest the timbral variety of a full orchestra.

Year 2024 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads