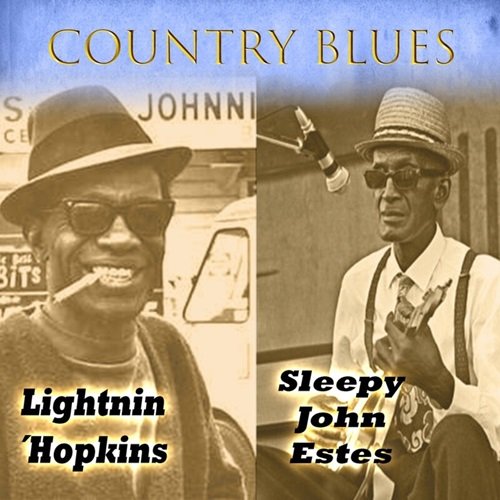

Lightnin' Hopkins:

Sam Hopkins was a Texas country bluesman of the highest caliber whose career began in the 1920s and stretched all the way into the 1980s. Along the way, Hopkins watched the genre change remarkably, but he never appreciably altered his mournful Lone Star sound, which translated onto both acoustic and electric guitar. Hopkins' nimble dexterity made intricate boogie riffs seem easy, and his fascinating penchant for improvising lyrics to fit whatever situation might arise made him a beloved blues troubadour.

Hopkins' brothers John Henry and Joel were also talented bluesmen, but it was Sam who became a star. In 1920, he met the legendary Blind Lemon Jefferson at a social function, and even got a chance to play with him. Later, Hopkins served as Jefferson's guide. In his teens, Hopkins began working with another pre-war great, singer Texas Alexander, who was his cousin. A mid-'30s stretch in Houston's County Prison Farm for the young guitarist interrupted their partnership for a time, but when he was freed, Hopkins hooked back up with the older bluesman.

The pair was dishing out their lowdown brand of blues in Houston's Third Ward in 1946 when talent scout Lola Anne Cullum came across them. She had already engineered a pact with Los Angeles-based Aladdin Records for another of her charges, pianist Amos Milburn, and Cullum saw the same sort of opportunity within Hopkins' dusty country blues. Alexander wasn't part of the deal; instead, Cullum paired Hopkins with pianist Wilson "Thunder" Smith, sensibly re-christened the guitarist "Lightnin'," and presto! Hopkins was very soon an Aladdin recording artist.

"Katie May," cut on November 9, 1946, in L.A. with Smith lending a hand on the 88s, was Lightnin' Hopkins' first regional seller of note. He recorded prolifically for Aladdin in both L.A. and Houston into 1948, scoring a national R&B hit for the firm with his "Shotgun Blues." "Short Haired Woman," "Abilene," and "Big Mama Jump," among many Aladdin gems, were evocative Texas blues rooted in an earlier era.

A load of other labels recorded the wily Hopkins after that, both in a solo context and with a small rhythm section: Modern/RPM (his uncompromising "Tim Moore's Farm" was an R&B hit in 1949); Gold Star (where he hit with "T-Model Blues" that same year); Sittin' in With ("Give Me Central 209" and "Coffee Blues" were national chart entries in 1952) and its Jax subsidiary; the major labels Mercury and Decca; and, in 1954, a remarkable batch of sides for Herald where Hopkins played blistering electric guitar on a series of blasting rockers ("Lightnin's Boogie," "Lightnin's Special," and the amazing "Hopkins' Sky Hop") in front of drummer Ben Turner and bassist Donald Cooks (who must have had bleeding fingers, so torrid were some of the tempos).

But Hopkins' style was apparently too rustic and old-fashioned for the new generation of rock & roll enthusiasts (they should have checked out "Hopkins' Sky Hop"). He was back on the Houston scene by 1959, largely forgotten. Fortunately, folklorist Mack McCormick rediscovered the guitarist, who was dusted off and presented as a folk-blues artist; a role that Hopkins was born to play. Pioneering musicologist Sam Charters produced Hopkins in a solo context for Folkways Records that same year, cutting an entire LP, Lightnin' Hopkins, in Hopkins' tiny apartment (on a borrowed guitar). The results helped introduced his music to an entirely new audience.

Lightnin' Hopkins went from gigging at back-alley gin joints to starring at collegiate coffeehouses, appearing on TV programs, and touring Europe to boot. His once-flagging recording career went right through the roof, with albums for World Pacific; Vee-Jay; Bluesville; Bobby Robinson's Fire label (where he cut his classic "Mojo Hand" in 1960); Candid; Arhoolie; Prestige; Verve; and, in 1965, the first of several LPs for Stan Lewis' Shreveport-based Jewel logo.

Hopkins generally demanded full payment before he'd deign to sit down and record, and seldom indulged a producer's desire for more than one take of any song. His singular sense of country time befuddled more than a few unseasoned musicians; from the 1960s on, his solo work is usually preferable to band-backed material.

Filmmaker Les Blank captured the Texas troubadour's informal lifestyle most vividly in his acclaimed 1967 documentary, The Blues Accordin' to Lightnin' Hopkins. As one of the last great country bluesmen, Hopkins was a fascinating figure who bridged the gap between rural and urban styles.

Sleepy John Estes:

Big Bill Broonzy called John Estes' style of singing "crying" the blues because of its overt emotional quality. Actually, his vocal style harks back to his tenure as a work-gang leader for a railroad maintenance crew, where his vocal improvisations and keen, cutting voice set the pace for work activities. Nicknamed "Sleepy" John Estes, supposedly because of his ability to sleep standing up, he teamed with mandolinist Yank Rachell and harmonica player Hammie Nixon to play the house party circuit in and around Brownsville in the early 1920s. The same team reunited 40 years later to record for Delmark and play the festival circuit. Never an outstanding guitarist, Estes relied on his expressive voice to carry his music, and the recordings he made from 1929 on have enormous appeal and remain remarkably accessible today.

Despite the fact that he performed for mixed Black and white audiences in string bands, jug bands, and medicine show formats, his music retains a distinct ethnicity and has a particularly plaintive sound. Astonishingly, he recorded for six decades on Victor, Decca, Bluebird, Ora Nelle, Sun, Delmark, and others. Over the course of his career, his music remained simple yet powerful, and despite his sojourns to Memphis and Chicago he retained a traditional down-home sound. Some of his songs are deeply personal statements about his community and life, such as "Lawyer Clark" and "Floating Bridge." Other compositions have universal appeal ("Drop Down Mama" and "Someday Baby") and went on to become mainstays in the repertoires of countless musicians. One of the true masters of his idiom, he lived in poverty, yet was somehow capable of turning his experiences and the conditions of his life into compelling art.