Tracklist:

1. Tre pezzi facili: No. 1, Valzer (02:17)

2. Preludio e fuga in G Minor (12:26)

3. Trittico ericino: No. 1, Meriggio festoso (02:13)

4. Evocazione (03:27)

5. Basso ostinato (04:52)

6. Umoresca (02:19)

7. Sonata in un tempo (11:27)

8. Tre pezzi: No. 1, Preludio agreste (02:53)

9. Tre pezzi: No. 2, Siciliana (03:45)

10. Tre pezzi: No. 3, Minuetto-Scherzo (02:23)

11. Corale e variazioni (15:24)

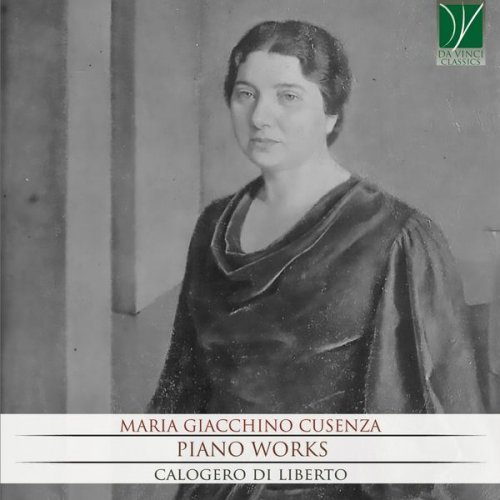

This CD dedicated to Maria Giacchino Cusenza (1898-1979) has the power of a rediscovery. Pianist and composer well-known locally, she impressed her strong personality on the cultural life and piano pedagogy in the Palermo of the twentieth century, far away from the Italian and European music circles in years which were vital for the development of contemporary musical languages.

Her main production dates back to the last years of the Fascist era, when Italy went through the nightmare of the Second World War, up to and including the post-war years. The Preludio e Fuga in G minor for piano (edited by Ricordi, 1936) marks the beginning of her mature career and is rewarded in 1937 by Accademia d’Italia [Academy of Italy]. In 1946 the Sonata in un tempo stood out into the Barbera publishing competition and in 1942 Canto Notturno (again edited by Ricordi) got the first prize at the “Ada Negri” competition. Until the start of the war, she wrote art songs and piano pieces marked by originality like Umoresca or the powerful Basso ostinato and still Tre pezzi and Aria e Danza for violin and piano (Ricordi, 1940). In 1941 Tre pezzi facili were published by Carisch, while pieces such as Evocazione and Trittico ericino remained unpublished. There are significant credits associated with these publications, starting with the award-winning Preludio e Fuga: “[…] excellent work, handled with talent” (Casella), “[…] with a magnificent technique both for harmonic taste and for the creation of the voice; both for the quality and for the soul, then for the pianism, really rich of effects and good taste” (Frazzi); “A piece admirably written and with a strong piano charm” (Pizzetti). In addition, Tagliapietra lauded its “fluidity and limpidity” and Tebaldini the majestic Fugue and “the successful first movement, which is rather reminiscent of a well-known composition by Debussy and becomes entirely expressed in the theme, hidden within the upper part that sings happily and spontaneously […]”. Other piano pieces were published by Ricordi in the mid-50s, in the midst of those experiments that led from integral serialism, born in Darmstadt as an extreme consequence of dodecaphony, to John Cage’s aesthetic of randomness. In 1954 the Studio esatonico and Studio canonico appeared, followed by Corale e variazioni (1955), which during the Fascism had been rewarded by the Sindacato Nazionale Musicisti [Musicians’ National Union], due to its well-defined music written with respect for the tradition.

The well-shaped music by Maria Giacchino, with sober titles showing early Italian and Bachian influences, and close to the Generation of the Eighties’ routes, is founded upon the experiences collected in years of intense concert and academic activity, with particular attention also to Beethoven and Debussy, until up to the achievement of the composition degree late in 1936. On her husband’s advice, the journalist Francesco Cusenza, in the 1930’s Maria resumed the study put on hold during First World War. Already an estimated teacher in the Conservatory, she started again to study with the colleague Mario Pilati, who was teaching composition in the Conservatory of Palermo while Antonio Savasta, formerly his teacher in Naples, was the director. Previously she had studied with Alberto Favara, an outstanding personality for his ethnomusicological research, his illustrious teaching and for the contribution to the musical renewal of the city, with actions as the first whole performances of some Symphonies by Beethoven at the just inaugurated Massimo Theatre (the interruption was due to the abolition of the composition course in 1917, when the director Guido Alberto Fano replaced the mild Francesco Cilea and immediately came into conflict with him).

On the other hand, Maria Giacchino’s craft on the piano was established on the school of Alice Ziffer, a pianist from Trieste who came to the Conservatory of Palermo in 1892 and soon joined the cellist Giacomo Baragli, both in the pioneering Società del Quintetto and in life (both of them had joined the instrumental music renewal projects carried out in Rome by Giovanni Sgambati). Within an exceptional family environment – her father, her sisters, her brothers Carmelo and Oreste were all musicians – Maria Giacchino was also sensitive to the Torregrossa’s and violinist Tùfari’s “expressive” teaching, then refining her technique with Fano. Thanks to him, she combined the deep “legato” and a more interpretative sensitivity with the Ziffer’s Lisztian technique. Finally she studied with Alfredo Casella, who in the 1920s, through the local section of the Corporazione delle Nuove Musiche in Palermo [Palermo New Music Guild], made the Sicilian capital a more worldly-wise city.

Her rigorous academic education affected her teaching at Conservatory for over forty years, from 1926 to 1970, with students such as Eliodoro Sollima and Sara Patera, Marisa Tanzini, Filomena Longo and her niece, Anna Maria. She had already gained teaching experience at home with her sister Livia and at the Cherubini Institute, an institution created in Palermo during the Belle Epoque to satisfy the growing demand of musical education. In the post-war years, from her teaching research, took origin Esercizi di lettura, divertimenti e studi, and the Sei personaggi in cerca di esecutori, easy pieces created under Pirandellian suggestions, which were intended for young pianists already capable of expressiveness.

In the 1920s Maria Giacchino began her concertistic activity in Italy and abroad, supported by a vast repertoire and an extraordinary memory, as well as by the new impetus at the Bellini Conservatory thanks to new teachers arrived from the peninsula, like Michelangelo Abbado and other distinguished violinists. In the same period, when the modern public concert flourished, she was one of the founding members of the Associazione Palermitana Concerti Sinfonici [Palermo Symphonic Concert Association] which was born alongside with the still living today Amici della Musica and with the above-mentioned experimental Guild that invited in Palermo even Bartók and Hindemith. As a critic, Maria Giacchino described the music of the Hungarian composer, which others defined “more acid than lemon juice”, “too distant and different from our spirit”. Always active in aristocratic circles, she also founded the Catholic Union of Italian Artists local section and played an important role in the Society of Writers and Artists, while in 1944 she was the member of a new Concert Society at the Conservatory.

Her activism was strengthened in the 1930s when, despite the greyness in which the city’s musical life had fallen, the professionalism accumulated in various “female” chamber music groups finally led to the creation of the Quintetto Femminile Palermitano, in which Maria also involved, as a cellist, her sister Maria Antonietta (Tonì). Besides, her little sister Livia was always right alongside her, as a piano teacher, in intense years of academic activity until the late twentieth century, inside a Conservatory full of ferments and important personalities to face with. To her, she left her important piano legacy, sweetened and transmitted with love to students who still teach there today.

(Album notes by Consuelo Giglio)