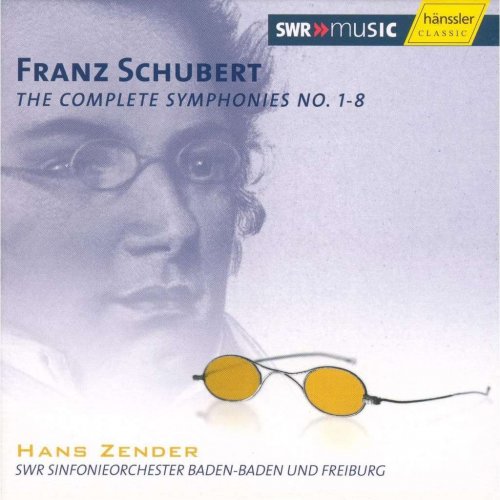

Hans Zender - The Complete Symphonies No. 1-8 (2004)

BAND/ARTIST: Hans Zender

- Title: The Complete Symphonies No. 1-8

- Year Of Release: 2004

- Label: hänssler Classic

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue,log,scans)

- Total Time: 4:14'29

- Total Size: 1.1 GB

- WebSite: Album Preview

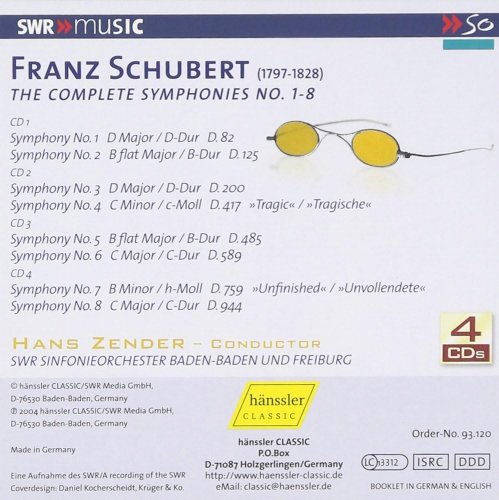

Tracklist:

Disc: 1

1 Adagio - Allegro Vivace

2 Andante

3 Menuetto. Allegretto - Trio

4 Allegro Vivace

5 Largo - Allegro Vivace

6 Andante - Variationen 1-5

7 Menuetto. Allegro Vivace - Trio

8 Presto Vivace

Disc: 2

1 Adagio Maestoso - Allegro Con Brio

2 Allegretto

3 Menuetto. Vivace - Trio

4 Presto Vivace

5 Adagio Molto - Allegro Vivace

6 Andante

7 Menuetto. Allegro Vivace - Trio

8 Allegro

Disc: 3

1 Allegro

2 Andante Con Moto

3 Menuetto. Allegro Molto - Trio

4 Allegro Vivace

5 Adagio - Allegro

6 Andante

7 Scherzo. Presto - Trio

8 Allegro Moderato

Disc: 4

1 Allegro Moderato

2 Andante Con Moto

3 Andante - Allegro Ma Non Troppo

4 Andante Con Moto

5 Scherzo. Allegro Vivace - Trio

6 Finale. Allegro Vivace

Disc: 1

1 Adagio - Allegro Vivace

2 Andante

3 Menuetto. Allegretto - Trio

4 Allegro Vivace

5 Largo - Allegro Vivace

6 Andante - Variationen 1-5

7 Menuetto. Allegro Vivace - Trio

8 Presto Vivace

Disc: 2

1 Adagio Maestoso - Allegro Con Brio

2 Allegretto

3 Menuetto. Vivace - Trio

4 Presto Vivace

5 Adagio Molto - Allegro Vivace

6 Andante

7 Menuetto. Allegro Vivace - Trio

8 Allegro

Disc: 3

1 Allegro

2 Andante Con Moto

3 Menuetto. Allegro Molto - Trio

4 Allegro Vivace

5 Adagio - Allegro

6 Andante

7 Scherzo. Presto - Trio

8 Allegro Moderato

Disc: 4

1 Allegro Moderato

2 Andante Con Moto

3 Andante - Allegro Ma Non Troppo

4 Andante Con Moto

5 Scherzo. Allegro Vivace - Trio

6 Finale. Allegro Vivace

An anomaly I've addressed in the above headnote has to do with Hänssler's odd and confusing re-re-numbering of the last two symphonies. As everyone surely knows by now, exhaustive scholarly research quite some time ago found compelling forensic evidence that Schubert's “Great” C-Major Symphony—long labeled No. 7—in fact postdated the “Unfinished,” (the No. 8). Thus it was that nearly half a century ago the C-Major was definitively renumbered No. 9. But that left a gap between six and eight, where seven used to be, just as there is a gap between 36 and 38 in Mozart's symphonies, where a work once believed to be by Mozart turned out to be, in the main, if I'm not mistaken, a work by Michael Haydn.

While most of us are not driven to anxiety attacks by such of life's minor inconsistencies, it seems that someone at Hänssler is unable to deal with the disorder of it all, and has compulsively eliminated the gap by designating the “Unfinished” No. 7 and the “Great” No. 8. The headnote numbers in parentheses are mine, designating the accepted numbers by which these two symphonies are known today. The explanation given in the booklet note is that the most recent research has now determined that the “Great” C-Major is in fact one and the same as a previously believed to be lost “Gmunden-Gastein” Symphony.

This is not a new theory, nor is it one that is universally accepted. But even if true, why this makes it necessary to renumber the “Unfinished” No. 7 and the “Great” No. 8 (a numbering scheme that, to my knowledge, has never been entertained by anyone) can only be the result of an obsessive-compulsive need to impose an imaginary order where none is required. If the “Great” and the “Gastein” are indeed one and the same, and the “Gastein-Great” does indeed post-date the “Unfinished,” then why not just continue to call it No. 9, and leave the “Unfinished” No. 8? Is it necessary to reduce the number of each by one in order to fill in the “hole”? This isn't dental work. No one would seriously suggest that we go back to Mozart's “Linz” Symphony (No. 36) and then reduce by one the number of each of the succeeding symphonies. It doesn't seem to bother anyone that we call the “Jupiter” No. 41, even though there are only 40 symphonies in the standard canon. This would only lead to further and unnecessary confusion. Frankly, having read a goodly amount of material on the subject of Schubert's on-again, off-again “missing” symphony, I've come to find the whole argument tiresome. Is Pluto a planet or isn't it? Are there nine planets in the solar system or only eight? According to Holst, there were only seven when he wrote The Planets, but that's because he omitted not only Pluto (it hadn't been discovered yet), but the Earth as well. Sounds right to me.

Number them as you will, I shall add my own fuel to the controversy by stating that Schubert wrote only two mature symphonies, and one of those (the “Unfinished”) is only a symphony by half. The six works leading up to the “Unfinished” stand in relation to Schubert's symphonic output as Mendelssohn's twelve string symphonies stand in relation to the latter's five full-blown symphonies. This is not meant to denigrate or diminish the early efforts of either composer. Schubert's first six symphonies were written between 1813 and 1818, or between the ages of 16 and 21, and his efforts produced beautiful music; of that there can be no doubt. Can anything be more captivating than the opening of the No. 5 in B?, with its pure-of-heart, spring-in-air tuneful opening?

All six works are essentially student compositions, written for the most part to be played by the amateur orchestra at the Stadtkonvikt boarding school that Schubert had attended, or by groups of musicians who gathered regularly at the Schubert home, where the young composer heard works by Haydn, Mozart, and Pleyel. It is doubtful whether at this early date Schubert had as yet been exposed to Beethoven. Schubert's one time teacher, Salieri, was not fond of the upstart from Bonn, and may have subtly or otherwise made negative comments about Beethoven to his impressionable young student.

Whatever may have happened, we know that Schubert stopped producing symphonies for at least four years, which in his short life of only 31 years, is a significant length of time. Depending on what authority is currently in vogue, there may or may not be a lost symphony, the so-called “Gmunden-Gastein,” from around this time. We do know that the so-called “Unfinished” dates from 1822, and the change in style represents a quantum leap in Schubert's symphonic-writing.

As an example of how history is constantly revised to fit the approved social standards of the day, we were told by our junior high school music teacher that Schubert fell ill with syphilis and died before he could finish the work. It didn't seem to trouble her that syphilis takes its toll over a long period, and that Schubert went on to write many works following his alleged death. By the time I got to high school, mores had changed; it was no longer acceptable to mention anything as nasty as syphilis in the classroom, and so now the story was that Schubert laid down his pen after the Andante because he realized the symphony's two complementary movements formed a perfect whole, and that nothing further could be said.

Both explanations are of course rubbish. For some reason, it never occurred to anyone that the B-Minor Symphony is called “Unfinished” because it really and truly is unfinished, as in not completed. We know this because sketches for a Scherzo movement, all the way up to the Trio section exist, proving that Schubert intended to write a full four-movement work. But like so many other projects he began and abandoned, the B-Minor Symphony is just another example, albeit perhaps the most magnificent torso of them all, of a work left by the curbside. This is why I stated earlier that Schubert wrote only one-and-a-half mature symphonies.

I believe it was Robert Schumann who referred to the “divine length” of Schubert's Seventh, Eighth, Ninth—or whatever you want to call it—“Great” C-Major Symphony. One man's divinity, I suppose, is another's devil. Personally, I have always found the piece almost as repetitious and wearing as Ravel's Bolero. But that's me. I haven't a lot of patience to sit through something that keeps on going, like the Energizer Bunny, long after it ought to have stopped. Schubert had wonderful ideas, and in songs and other short forms he was the master of his domain. But in large forms, he often seemed to lose control over his material, not quite knowing when and how to bring it to an end. Pace Schumann, the symphony simply exceeds the reasonable expectations of its material. It's not simply a matter of time. Beethoven's Ninth goes on for even longer. But in the Beethoven, there is always a sense of momentum, of the material developing and moving forward. In Schubert's “Great,” there is a sense of stasis, of being stuck in a groove, with the same patterns being repeated over and over again.

I realize that in saying this I am proclaiming a heresy, for Schubert's “Great” has been adjudged one of the towering pinnacles of the symphonic literature. So, rather than risk excommunication, I will just say that Zender's reading of the work, as well as all of the other symphonies, is superb. He is quite successful at pacing the tricky transition from the Andante to the Allegro in the first movement of the “Great.” These are first-class performances. They are not on period instruments, nor are they particularly fleet or light of foot in the ways of modern-instrument ensembles that have been historically “re-programmed.” Zender approaches Schubert as a full-blown Romantic composer, yet he and his charges manage to avoid any opaqueness or bloating of the orchestration, and they keep things clean enough to allow inner details of the scores to emerge nicely.

I liked these recordings very much, and I can definitely recommend them..."

While most of us are not driven to anxiety attacks by such of life's minor inconsistencies, it seems that someone at Hänssler is unable to deal with the disorder of it all, and has compulsively eliminated the gap by designating the “Unfinished” No. 7 and the “Great” No. 8. The headnote numbers in parentheses are mine, designating the accepted numbers by which these two symphonies are known today. The explanation given in the booklet note is that the most recent research has now determined that the “Great” C-Major is in fact one and the same as a previously believed to be lost “Gmunden-Gastein” Symphony.

This is not a new theory, nor is it one that is universally accepted. But even if true, why this makes it necessary to renumber the “Unfinished” No. 7 and the “Great” No. 8 (a numbering scheme that, to my knowledge, has never been entertained by anyone) can only be the result of an obsessive-compulsive need to impose an imaginary order where none is required. If the “Great” and the “Gastein” are indeed one and the same, and the “Gastein-Great” does indeed post-date the “Unfinished,” then why not just continue to call it No. 9, and leave the “Unfinished” No. 8? Is it necessary to reduce the number of each by one in order to fill in the “hole”? This isn't dental work. No one would seriously suggest that we go back to Mozart's “Linz” Symphony (No. 36) and then reduce by one the number of each of the succeeding symphonies. It doesn't seem to bother anyone that we call the “Jupiter” No. 41, even though there are only 40 symphonies in the standard canon. This would only lead to further and unnecessary confusion. Frankly, having read a goodly amount of material on the subject of Schubert's on-again, off-again “missing” symphony, I've come to find the whole argument tiresome. Is Pluto a planet or isn't it? Are there nine planets in the solar system or only eight? According to Holst, there were only seven when he wrote The Planets, but that's because he omitted not only Pluto (it hadn't been discovered yet), but the Earth as well. Sounds right to me.

Number them as you will, I shall add my own fuel to the controversy by stating that Schubert wrote only two mature symphonies, and one of those (the “Unfinished”) is only a symphony by half. The six works leading up to the “Unfinished” stand in relation to Schubert's symphonic output as Mendelssohn's twelve string symphonies stand in relation to the latter's five full-blown symphonies. This is not meant to denigrate or diminish the early efforts of either composer. Schubert's first six symphonies were written between 1813 and 1818, or between the ages of 16 and 21, and his efforts produced beautiful music; of that there can be no doubt. Can anything be more captivating than the opening of the No. 5 in B?, with its pure-of-heart, spring-in-air tuneful opening?

All six works are essentially student compositions, written for the most part to be played by the amateur orchestra at the Stadtkonvikt boarding school that Schubert had attended, or by groups of musicians who gathered regularly at the Schubert home, where the young composer heard works by Haydn, Mozart, and Pleyel. It is doubtful whether at this early date Schubert had as yet been exposed to Beethoven. Schubert's one time teacher, Salieri, was not fond of the upstart from Bonn, and may have subtly or otherwise made negative comments about Beethoven to his impressionable young student.

Whatever may have happened, we know that Schubert stopped producing symphonies for at least four years, which in his short life of only 31 years, is a significant length of time. Depending on what authority is currently in vogue, there may or may not be a lost symphony, the so-called “Gmunden-Gastein,” from around this time. We do know that the so-called “Unfinished” dates from 1822, and the change in style represents a quantum leap in Schubert's symphonic-writing.

As an example of how history is constantly revised to fit the approved social standards of the day, we were told by our junior high school music teacher that Schubert fell ill with syphilis and died before he could finish the work. It didn't seem to trouble her that syphilis takes its toll over a long period, and that Schubert went on to write many works following his alleged death. By the time I got to high school, mores had changed; it was no longer acceptable to mention anything as nasty as syphilis in the classroom, and so now the story was that Schubert laid down his pen after the Andante because he realized the symphony's two complementary movements formed a perfect whole, and that nothing further could be said.

Both explanations are of course rubbish. For some reason, it never occurred to anyone that the B-Minor Symphony is called “Unfinished” because it really and truly is unfinished, as in not completed. We know this because sketches for a Scherzo movement, all the way up to the Trio section exist, proving that Schubert intended to write a full four-movement work. But like so many other projects he began and abandoned, the B-Minor Symphony is just another example, albeit perhaps the most magnificent torso of them all, of a work left by the curbside. This is why I stated earlier that Schubert wrote only one-and-a-half mature symphonies.

I believe it was Robert Schumann who referred to the “divine length” of Schubert's Seventh, Eighth, Ninth—or whatever you want to call it—“Great” C-Major Symphony. One man's divinity, I suppose, is another's devil. Personally, I have always found the piece almost as repetitious and wearing as Ravel's Bolero. But that's me. I haven't a lot of patience to sit through something that keeps on going, like the Energizer Bunny, long after it ought to have stopped. Schubert had wonderful ideas, and in songs and other short forms he was the master of his domain. But in large forms, he often seemed to lose control over his material, not quite knowing when and how to bring it to an end. Pace Schumann, the symphony simply exceeds the reasonable expectations of its material. It's not simply a matter of time. Beethoven's Ninth goes on for even longer. But in the Beethoven, there is always a sense of momentum, of the material developing and moving forward. In Schubert's “Great,” there is a sense of stasis, of being stuck in a groove, with the same patterns being repeated over and over again.

I realize that in saying this I am proclaiming a heresy, for Schubert's “Great” has been adjudged one of the towering pinnacles of the symphonic literature. So, rather than risk excommunication, I will just say that Zender's reading of the work, as well as all of the other symphonies, is superb. He is quite successful at pacing the tricky transition from the Andante to the Allegro in the first movement of the “Great.” These are first-class performances. They are not on period instruments, nor are they particularly fleet or light of foot in the ways of modern-instrument ensembles that have been historically “re-programmed.” Zender approaches Schubert as a full-blown Romantic composer, yet he and his charges manage to avoid any opaqueness or bloating of the orchestration, and they keep things clean enough to allow inner details of the scores to emerge nicely.

I liked these recordings very much, and I can definitely recommend them..."

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads