Tracklist:

1. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Primo discorso eretico sulla leggerezza dei chiodi (07:51)

2. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Sand Sculptures: I. The Pro Sand Art Band (01:30)

3. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Sand Sculptures: II. Tired Flatfish Admires Playful Dolphins (01:20)

4. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Sand Sculptures: III. Medieval King Makes Proposal on a Tactical Map (01:04)

5. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Sand Sculptures: IV. Scorpions Provoke a Top-Hatted Elephant (02:16)

6. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Sand Sculptures: V. DJ Octopus (02:28)

7. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Il respiro nel silenzio (07:49)

8. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Obtuser Air (10:11)

9. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – La favola di Antonio e Marsia (07:17)

10. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Pagina d'album (03:15)

11. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Ballade (10:22)

12. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Invitation (04:48)

13. Sauro Berti & Leonardo De Marchi – Enantiosemie (05:32)

14. Matteo Evangelisti – Trio No. 1: I. Allegro giocoso (For Flute, A Clarinet and Guitar) (05:34)

15. Matteo Evangelisti – Trio No. 1: II. Largo (For Flute, A Clarinet and Guitar) (05:02)

16. Matteo Evangelisti – Trio No. 1: III. Allegro (For Flute, A Clarinet and Guitar) (03:18)

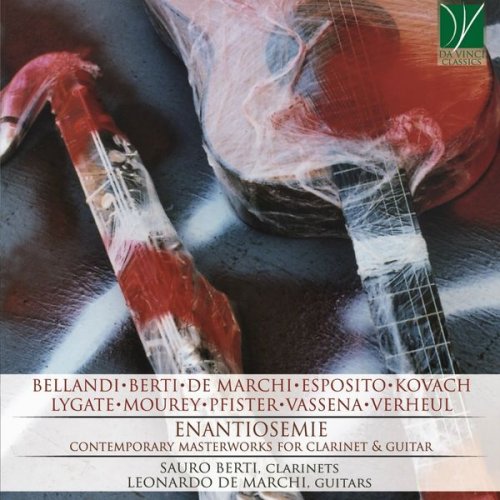

The repertoire for clarinet-guitar duo, emerging in the nineteenth century musical salons, has grown steadily over the last fifty years; this unusual combination of instruments has given rise to a great number of different and often contrasting musical languages. Entitling this album “Entantiosemie” – that is to say, words which can mean one thing and also its opposite- signifies the desire not only to show how the clarinet and guitar have been able to and still do interpret innumerable styles and research modes often diametrically opposed to each other, but also how the performer can interpret the same score in completely different ways. In fact, all art forms teach us that a single word can unleash a host of contrasting emotions.

One could not but open a CD based on at least apparent contradictions with anything other than “Primo discorso eretico sulla leggerezza dei chiodi” [“First heretical discourse on the lightness of nails”] (2000) by Nadir Vassena (born 1970), a piece written for Mats Scheidegger (born 1963) and Harry Sparnaay (1944-2017) which owes its dramatic character to sudden pauses and brusque juxtapositions of assorted materials. The title is a thought-provoking oxymoron which, referring in a provocative manner to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, leads us, even before the start of the piece, to imagine harsh and irregular sounds, shifting backwards and forwards between two apparently irreconcilable poles of ethereal lightness and pungent hardness. The bass clarinet and guitar are the interpreters of a form of musical writing which, thanks to an impressive array of resources of timbres and instrumental techniques, analyses the material dimensions of sound down to its most basic components. Manifold types of attack, the constant research for non-equable intonation and the conspicuous use of hypo-sounds and multiphonics, enliven the narration which is always lively and taut. By way of contrast, the five movements of “Sand sculptures” (2011) by Scott Lygate (born 1989) create an ironic sound fresco like a popular song, inspired by some sculptures in the sand he had seen and admired in Portugal, after which each movement of the suite is entitled. Lygate gives a demonstration of his minute knowledge of the most extended techniques on both the instruments. The result is particularly evocative, in that it is not difficult for the listener to recognise the crossover played by the “Pro-Sand Art band”, the surreal calm in “Tired flatfish admires playful dolphins”, the grotesque declamatory pose of the king in “Medieval king makes proposals on a tactical map”, the trumpeting of the terrified elephant in “Scorpions provoke a top-hatted elephant” and the wild, cacophonous scratching of “DJ octopus”. The atmosphere in “Il respiro del silenzio” [“The breath of silence”] (2017) by the Roman composer Patrizio Esposito (born 1960) is definitely darker and gloomier. It is evident right from the start that the score depicts an uneasy, tenebrous night: from time to time jackals appear in front of our eyes tearing the darkness apart with their fearful cries, wind instruments play disturbing melodies and we are aware of other presences with their uncertain outlines, apparently created by the mist. Esposito succeeds perfectly in uniting the low bass clarinet tessitura with the pointillism of the guitar, in fact the subtle and meticulous research into nuances of timbre and dynamics are the writing’s strong-point. The Dutch composer Maurice Verheul (born 1964) has dedicated a lot of solo and chamber works to the bass clarinettist Harry Sparnaay. In “Obtuser air” (2016), his first work for duo with guitar, the instruments enter into a dialogue with each other on absolutely equal terms, in an uninterrupted interplay of themes and motives from one instrument to the other. The material of the piece derives from a single rhythmic cell, a tresillo, which characterises a great deal of Latin-American music. Here Verheul puts it through a continuous process of deformation: the result is an alienating, contemplative character, sometimes not without a certain element of grotesqueness. The ironic tendency of the composer emerges also in the title “Obtuser air”, which is nothing less than an anagram of Sauro Berti, to whom the work is dedicated.

After the dialogue with the traditional guitar, the bass clarinet, for the first time in its history, plays together with a ten-string guitar, an instrument which, thanks to its supplementary bass notes, has a sound quality rich in resonances. This original union of instruments takes place in “La favola di Apollo e Marsia” [“The myth of Apollo and Marsyas”] (2017) by Antonio Bellandi (born 1974), a piece in which the action of the drama adheres faithfully to the myth of Apollo and Marsyas, as recounted by the Latin writer Iginus. Iginus tells of how the goddess Minerva makes a flute from a deer bone but then throws it away, as she is mocked by Venus and Juno for the faces she pulls when playing it. The instrument is picked up by the Silenus, Marsyas who starts practising on it making ever-sweeter sounds; his presumption drives him to challenge Apollo to a musical contest, the God playing his cithara. Marsyas seems to be winning until Apollo turns his instrument upside down and plays exactly the same music, something which Marsyas can’t manage to do. The god ties the defeated Marsyas to a tree and then hands him over to a Scythian who flays his corpse; then he hands over what is left of the body of the satyr to his disciple Olympus to bury it. The use of extended techniques, and in particular of the unique possibilities of sounds offered by the ten-string guitar, permit the composer to describe explicitly the salient points of the story: in particular he exploits to the full the booming clusters in the low register and the auras created by resonances, using harmonics and percussion on the body of the instrument.

“Ballade” by Hugo Pfister (1914-1969), the only piece on this CD belonging to the tiny classical repertoire for clarinet and guitar, is noteworthy on account of its generally severe and gloomy atmosphere. It was probably composed in 1959, at the end of the Swiss composer’s studies with Nadia Boulanger; the “Ballade” is a formally ambitious piece, in a dry style, not generally on the look-out for unusual sounds. The macro-structure of the piece is clearly articulated in episodes of contrasting moods. The material is drawn entirely from the initial guitar motive and the two instruments engage, with equal importance, in a close dialogue, of a highly demanding and virtuoso nature.

To lighten the dark-tinted atmosphere of Pfister’s ballade there now intervenes the concise “Invitation. Tribute to Harry Sparnaay” by the French composer Colette Mourey (born 1954; she was later to dedicate the larger scale piece entitled “Blues sonata” to the duo Berti-De Marchi). This Tribute is based, like the preceding one, on alternating sections of a contrasting nature. The mood swings from witty to pungent and then to rhapsodic in its sudden shifting from one section to the next. The bass clarinet is often pushed up to its highest register, creating an agile and diaphanous persiflage, with the writing for the guitar using an idiom which recalls the lesson of the twelve studies by Hector Villa-Lobos.

The CD closes with the “Trio n.1 (Musique d’automne)” (1942) for flute, clarinet in A and guitar by the Rumanian composer (later naturalised Swiss) Andor Kovach (1915-2005). The guitar, which in the earlier pieces was a protagonist, now leaves the stage partially to the two wind instruments, being content to supply the harmony and rhythm on which the flute and clarinet develop their respective melodic lines. The refined and elegant character of Kovach’s Trio reveal his debt to the past in its adoption of formal models canonised by tradition: the first movement is in sonata form, the second is a mournful melody over a guitar ostinato and the third is a particularly lively and witty rondo.

It will not have escaped the notice of the attentive listener that in two pieces, both written in August 2018, the CD’s performers are also their composers! “Pagina d’album” by Leonardo De Marchi is a sort of intermezzo in ternary form and its lyrical atmosphere – with a quotation from Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in blue” and from another piece on this CD, the identity of which we won’t reveal!-acts as a fleeting intermezzo between the heavier works of Bellandi and Pfister. “Enantiosemie” by Sauro Berti on the other hand seems to suggest to us, with the simultaneous use of four metronomes which the interpreters have to follow, that the linear, ordered and strict perception of the tempo can paradoxically lead to a contrary result with the interpreters annulling in turns the rigid order of the tocks of the simultaneous beats of the metronomes. The performers have to play the same parts, purposely lacking in expression marks, but the different tempo indications suggest diverse interpretations. When it comes down to it, it is precisely this continuous shifting from one concept to its opposite which represents a miraculous example of enantiosemy.

Album Notes by Leonardo De Marchi