Tracklist:

1. Tres Piezas Originales en Estilo Español, Op. 1: No. 1, Bolero (04:39)

2. Tres Piezas Originales en Estilo Español, Op. 1: No. 2, Habanera (06:45)

3. Tres Piezas Originales en Estilo Español, Op. 1: No. 3, Seguidillas gitanas (06:50)

4. Trio No. 2 in B Minor, Op. 76: No. 1, Lento - Allegro molto moderato (06:23)

5. Trio No. 2 in B Minor, Op. 76: No. 2, Molto vivace (02:36)

6. Trio No. 2 in B Minor, Op. 76: No. 3, Lento - Andante mosso - Allegretto (05:12)

7. Trio in A Minor: No. 1, Modéré (10:09)

8. Trio in A Minor: No. 2, Pantoum. Assez vif (04:28)

9. Trio in A Minor: No. 3, Passacaille. Très large (08:26)

10. Trio in A Minor: No. 4, Final. Animé (05:22)

For us, the musical program in this album has a strong pictorial component. The trios featured capture the reciprocal influences across Spanish and French culture during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with Turina drawing heavily on the musical language of the French impressionists and Ravel incorporating the rhythm of Basque folkloric dances into the opening theme of his trio. Moreover, the vivid musical colours and gestures present in all three works unmistakably mirror those in the paintings by the great impressionists. The unapologetic display of the brushstroke in paintings by Monet, Pissarro and the like, in defiant reply to the concealed, perfectionist technique of the academic traditionalists, seems to be echoed in the vibrant, sweeping flurries of the music. We find this characteristic present not only in the two impressionist trios but also in Arbos’ dances: three evocative, lyrical precursors to this aesthetic. This parallelism, in our opinion, provides an even more relevant running thread throughout the album.

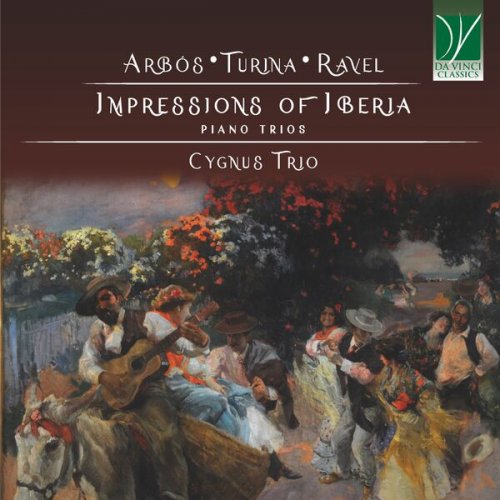

During our preparation towards the recording, we kept being drawn to the works of Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla. He, like Turina, was transformed by his stay in Paris where, having been exposed to the works of the French avant-garde, he took his art in a new direction. His depictions of Iberian folklore in colourful, freely sketched tableaux strongly reminded us of the music we were rehearsing, yes, in their subject matter but, more abstractly and more deeply, in their light, dynamism and particular poetry. So much so that we wanted to include one of his paintings, titled “La última copla”, as the cover of the album. Of course, this small reproduction could never convey the magic of the original, but we hope it will give the listener a glimpse of the captivating world this album inhabits.

The Cygnus Trio © 2024

The form of the piano trio is one of the most august and celebrated in the Western classical tradition. It features a very balanced timbral combination, with the two bowed string instruments (violin and cello) covering, together, a range similar to that of the piano. They balance each other in a fashion not very dissimilar from the pianist’s two hands; while at the same time, providing a marked contrast with the piano’s timbre and attack of sound.

At a time (between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries) when timbral research was beginning to fascinate composers more and more, but when traditional formal structures were being increasingly disregarded, three composers of Iberian descent (but with important connections to the musical world of Northern Europe) tackled the challenge represented by this genre, producing three masterpieces which are recorded here.

Enrique Fernández Arbós and Joaquín Turina were Spaniards who studied in French-speaking countries (France and Belgium); Maurice Ravel was a French composer of Basque descent (and, in particular, his Trio is one of the pieces where his ancestry is shown most typically).

Arbós was born on Christmas Day, 1863; his family was active in the field of music, and the child soon showed signs of musical disposition. His first education took place at the Conservatory of Madrid, under the guidance of Jesús de Monasterio y Agüeros, who – as his disciple would later become – was proficient as a violinist, composer, conductor, and pedagogue.

Promoted by his teacher, Arbós obtained a scholarship for studying abroad in Belgium, where he received tuition from such great musicians as Henri Vieuxtemps and François- Auguste Gevaert. In the latter’s class, Arbós met and befriended a fellow student and countryman, Isaac Albéniz, with whom he would also play as a duo. After four years in Brussels, Arbós continued his studies in Berlin, where his teachers were legendary violinist Joseph Joachim and composer Heinrich von Herzogenberg.

From then on, his career began to flourish, and he became the much-respected concertmaster of several important orchestras (from the Berlin Philharmonic to the Boston Symphony, to name but two).

A period in London proved very fruitful for Arbós, both musically and professionally. He was invited to teach violin at the Royal College of Music, and, during his prolonged residency in the British capital, he became an appreciated conductor. In 1904, the Madrid Symphony Orchestra invited him as its conductor (a post he would maintain for many years), and, with this important ensemble or as a guest conductor of other orchestras, he toured Europe extensively and was also acclaimed in the United States. Unfortunately, however, the intensity of Arbós’ schedule as a performing musician prevented him from dedicating time and energy to his own compositions, and this is a regrettable loss.

Arbós’ familiarity with the sound and idiosyncratic traits of the piano trio is due to another of his activities: that of violinist in a piano trio. The so-called Trio Arbós had been established first during the violinist’s student years in Brussels (with Agustín Rubio and Alejandro Rey Colaço). Later, Isaac Albéniz joined the ensemble as a pianist, and the three musicians presented themselves as The Iberian Trio.

In spite of this, it was with yet another ensemble that Arbós premiered his Piano Trio called Tres Piezas Originales en Estilo Español a composition which proudly displays opus number “1”. This bears witness to the importance Arbós assigned to his youthful composition and to how he regarded it as seminal.

The work, composed during Arbós’ stay in Berlin, was performed in Brussels in 1888 by the composer with pianist Pilar de la Mora and cellist Eduard Jacobs. It had already appeared in print two years earlier, and had been tried out several times privately, including performances with another legendary musician, Hans von Bülow.

The work is in three movements, but its structure mirrors more closely that of a Suite than that of a traditional piano trio. In fact, the three movements all bear titles which reflect typical dances of the Iberian tradition. The first movement is a Bolero, an enthralling piece which represents the gestures and postures of the classical dance in triple time. It is followed by a Habanera: both of these dances already had a long history of being included in “Classical” works – from Chopin to Bizet, to name but two. Notwithstanding his deliberate adoption of the august lineage of these dances, Arbós intervenes creatively within their frame, producing innovative readings of the traditional schemes. The Habanera, in particular, is noteworthy for its refined use of chromaticism, with a modern tinge which contributes positively to a creative reception of the model. The concluding Seguidillas gitanas is the perfect blend of Iberian (and gypsy) singing and dancing, alternating and combining passages where the cantabile element is more pronounced with others whose rhythmic drive is more intense. Arbós was so fond of this composition – which is probably his only work to be regularly played at an international level – that he orchestrated its two outer movements, which achieved considerable fame.

A different kind of Spain, also mirroring the other Trio’s very different circumstances of compositions, is found in Turina’s Second Piano Trio. Turina was born in Seville, in 1882.

Similar to Arbós, Turina was a child prodigy; in this case, his musicianship became evident when, without any teaching, he demonstrated extraordinary ability in playing an accordion he had received as a present from his nanny. He was soon encouraged to study music, and was fortunate enough to find an excellent teacher of harmony and counterpoint, Evaristo García Torres. Still in his teens, Turina acquired fame as a virtuoso pianist with an orchestra founded by himself.

At the age of 20, Turina moved to Madrid where he continued his studies and met with important figures of his time. Within the space of a few years, the young musician was orphaned; the positive aspect of this tragedy was that it encouraged him to settle in Paris, where he studied piano with Moritz Moszkowski and became deeply and increasingly engaged in composition. The unveiling of the young musician to the Parisian world of music came with his performance of a Piano Quintet he had composed: such was the impression it created, that Albéniz undertook its revision and promoted its publication. Turina also befriended Arbós, and, as a token of esteem, dedicated to him his first tone poem, La Procesión del Rocío op. 9 (1912). In the following years, Turina progressively conquered a place as a figure of reference in the world of music, and was the protagonist of important productions and long tours (including one in America).

However, the composer would also experience another personal tragedy: one of his daughters, María, died at 18 in 1932. Furthermore, the following years, with the Spanish Civil War and World War II, were very hard on him, and it was only thanks to the direct intervention of the British Embassy ( whose offices had given him a British passport) that he and his dear ones made it through the war.

It was precisely during the trying time following María’s death that Turina composed his Trio op. 76, which was completed in early 1933. Its dedicatee is Jacques Lerolle, Turina’s first publisher and the nephew of Ernest Chausson.

The first movement combines several episodes with contrasting characters, interweaving pathos with suggestions of dance, singing and quasi-orchestral writing. The second movement is a brilliant scherzo with pronounced Iberian features, framing, by its outer sections, a calmer core. The third movement also includes marked oppositions, as, for instance, that between the spiritual, chorale-like sections, and the fresh atmosphere of a dancing Allegretto; the conclusion is brilliant and memorable.

Hard times also underlie the composition of Maurice Ravel’s Piano Trio. The composer was spending the summer of 1914 in the Basque village of Saint-Jean-de-Luz, very close to the town when he had been born (Ciboure). The composer allowed himself to be deeply influenced and shaped by the music he heard there, by the Basque atmospheres, and by the context he was experiencing. The genesis of this piece was sporadic. A first stage of writing was rather inconstant, and frequently interrupted. However, when World War I became imminent, Ravel was prompted to complete his unfinished work before leaving for the battlefield, and, therefore, he could quickly write a work that, ordinarily, it would have taken him months to complete.

The piece was premiered in Paris’ Salle Gaveau in January 1915, with pianist Alfredo Casella, violinist Gabriel Wuillaume (or possibly George Enescu) and cellist Louis Feuillard.

The Basque influence is particularly evident in the first movement, Modéré, whose inspiration is derived from the Basque dance called zortzico (although it was later claimed that Ravel mistook for a genuine zortzico something which was in reality a bourgeois version of it!). The second movement goes further in its quest for exoticism, albeit of a very special kind. Its title, Pantoum, refers to a poetic form of Malayan poetry, which requires particular virtuosity of its author (and which had been employed by the most important Symbolist poets of Ravel’s time). The composer accepted the challenge of writing a musical piece with a generative process reminiscent of that underlying the literary pantoum.

The third movement, instead, is “exotic” in relation to time, as it refers back to Baroque dancing and to its majestic and refined atmospheres, as well as to the complex writing of counterpoint. This is all forgotten in the brilliant, playful, and highly original finale (Animé), completing the work in a spectacular fashion.

Together, these three works offer the listener a beautiful experience of the dialogue between Spanish tradition and modernity, on the threshold dividing the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, fin-de-siècle and contemporaneity.