Tracklist:

1. Années de Pèlerinage III, S. 163: No. 4, Les jeux d'eaux à la Villa d'Este (09:19)

2. 2 Légendes, S. 175: No. 1, St François d'Assise: la prédication aux oiseaux (11:42)

3. Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, S. 173: No. 1, Invocation (09:13)

4. Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, S. 173: No. 7, Funérailles (13:15)

5. Années de pèlerinage I, S. 160: No. 6, Vallée d'Obermann (16:24)

The Romantic soul and the worldview it adhered to were deeply fascinated by infinity. This longing, this desire and this aspiration could manifest themselves in a variety of forms. Nature was seen by the Romantics no longer as a power tamed by humankind, as in the regular, geometric and architectural gardens of Baroque and Enlightenment taste; rather, it was admired in its sublimity, in its horrors and in its overwhelming force. Gazing at the sky, the Romantics felt an inexpressible awe and amazement, which translated into a deep nostalgia for something beyond the human. Sometimes, this longing became a true religious feeling: not merely the primeval sentiment of transcendence, impersonally and sometimes cruelly embodied by Nature’s powers, but an encounter with the God of Christian revelation. Finally, this longing for the otherworldly also took the form of a cult for geniuses, heroes, martyrs and artists: those humans who could cross the boundaries of mediocrity, and elevate themselves beyond what is accessible to most people, were worshipped and revered. They represented the struggle – as well as the God- or Nature-given talents – through which humans could become, as it were, superhuman.

The figure of Franz Liszt represented all of these elements in a powerful and almost unique fashion. In his youth, he toured extensively as one of the most appreciated, idolized, admired and adored virtuosos of all times. He had been able to push the boundaries of piano technique well beyond what had hitherto been imaginable. His capability to make the piano sound as an orchestra, to master the most difficult technical challenges, and to move to tears his listeners were allegedly unequalled. He was a true “hero” of the piano; an artist who had the skill for expressing the most intense feelings of his soul and also of his culture. Moreover, his figure and his provenance embodied the nationalistic and patriotic stance of many Romantics; also under this profile, thus, he was the prototype of the Romantic hero.

His music was also thought to convey those feelings of Nature’s sublimity which the Romantic soul cherished so much. He was able to realize this thanks to a variety of tools. Thanks to its many contrasts in volume, timbre and texture, his music seemed to represent the abysses, the peaks, the rustlings and the thunderings, the murmurs and the rumblings of Nature’s most powerful expressions. Moreover, his novel use of piano technique could also generate new solutions for aurally representing specific natural phenomena, such as birdsong or waterfalls or waves, to name but few. The Romantics’ attraction for Nature could thus find an outlet in Liszt’s music, and, through the contemplation of natural phenomena, reach the feelings of sublimity and awe so treasured by the Romantics.

Last but not least, the pianist and composer was also deeply interested in the religious aspect of life. Although his lifestyle did not always conform to the precepts of Catholic morals, he constantly felt – from his early youth to the grave – the appeal of transcendence. As a teenager, he had wished to enter the Seminary of Paris, but had been discouraged by both his mother and the priest who was his spiritual father. A few years later, he wrote an essay on Church music, thus testifying to the stable link between his faith and his music. It was however in his maturity that his religious inspiration and interest manifested themselves most clearly. He lived for a long time in Rome, was admitted to the “minor” holy orders (i.e. those which normally precede the ordination to priesthood) and began composing a constantly increasing number of sacred or religious works, sometimes destined for liturgical worship, sometimes for the concert hall or the salon.

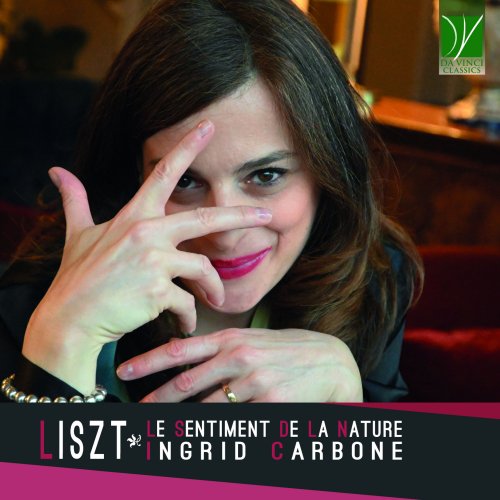

The works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album are a perfect representation of Liszt’s many souls, and of this longing for infinity, expressed in so many different ways.

There is undoubtedly the virtuoso dimension: many of the pieces recorded here ask for transcendental virtuosity and absolute mastery of piano technique, at its most demanding level. There are the transparent arpeggios of Les jeux d’eau, the octaves of Funérailles, the powerful chords of Vallée d’Obermann… to mention but a handful of the most famous technical passages of piano literature.

There is also the evocation of Nature, represented in its multifaceted aspects: the impressive sublimity of Vallée d’Obermann, the game of waterdrops against light in Les jeux d’eau, the twitterings and chirpings of the birds in Saint François d’Assise, along with many more creative depictions.

There is, perhaps most important of all, the religious dimension, sometimes expressed in a very clear fashion, sometimes appearing in unexpected forms and at unexpected places. For example, Les jeux d’eau à la Villa d’Este is a piece which seems, at first sight, to be “just” a pre-Impressionistic portrayal of water’s lightness. Doubtlessly, this work did appeal to the subsequent generation of Impressionist composers, and became a model for countless later depictions of similar natural phenomena, most famously in Maurice Ravel’s Jeux d’eau. However, Liszt inserted a Gospel quote at the piece’s core, and this inscription reveals a hidden meaning which goes far beyond the coloristic evocation. The quote, excerpted from the Gospel of St. John, refers to the water of Baptism as a symbol for the Holy Spirit, poured by Christ in the souls of the faithful. Following their Master’s example, Christian believers are turned into “sources” of “living water”, which springs from their hearts for eternal life.

Religiosity also permeates another seemingly coloristic piece, the Legend depicting St Francis of Assisi preaching to the birds. Liszt, whose first name was Franz, devoutly wrote two piano “Legends” dedicated to two great saints whom he considered as his patrons: St Francis of Assisi and St Francis of Paola; the piece dedicated to the latter saint has also been recorded for Da Vinci Classics by the same performer. The episode portrayed in the work recorded here is excerpted from the “Little Flowers of St Francis”, a collection of short stories transmitted by the Saint’s most faithful companions. St Francis, though no proto-ecologist, was however deeply fascinated by nature and by the animals he encountered; he considered all creatures as being manifestations of God’s Providence, and capable, in their own fashion, to praise Him and give Him glory. Thus, on one occasion, St Francis spoke to a number of birds gathered on a tree, inviting them to express their prayerful response to their Creator by means of their song. This episode gave the opportunity to the composer for turning the piano into a “catalogue d’oiseaux”, just as Olivier Messiaen would do a century later; here too, however, the piece’s deepest meaning is not in the superficial appearance of the birdsongs but rather in the spiritual significance of the episode.

A prayer is also depicted in Invocation, a piece taken, along with Funérailles, from a rather heterogeneous collection called Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, which includes very virtuoso and imposing pieces along with small-scale miniatures with a chamber music touch. Invocation is inspired by a poem by Alphonse de Lamartine, whose lines are quoted in the score. It depicts the soul’s invocation of God, in a prayer which elevates itself rising “with the dawn, with the night”, or “like a flame”, or floating “on the wing of the clouds”. This imagery is powerfully evoked by Liszt’s effectful piano writing.

A literary influence is also found in Vallée d’Obermann, inspired by an epistolary novel written at the dawn of the nineteenth century but which achieved the summit of its fame only a few decades later. The portrayal of nature, as experienced by the eponymous character, resonated deeply in Liszt’s soul, when he was travelling through Switzerland; his music attempts, and successfully manages, to achieve the same grandiosity, sublimity and fascination of Nature.

In Funérailles, it is Liszt the patriot who comes to the fore. Although the piece forcefully reminds the listener of certain passages written by Chopin, who had recently died and whom Liszt deeply revered, the ultimate inspiration came to Liszt from the death or exile of three martyrs of Hungary’s rebellion against the Austrian rulers. The piece is dark, veined by piety and sorrow, but also eliciting feelings of heroism, of patriotic enthusiasm, of longing for a freedom which still had to be conquered and obtained.

Here too the religious dimension is not missing: the rays of hope and tenderness contained in certain of its most touching episodes confer to the tragedy of these martyrs a spiritual dimension. The ultimate meaning of their sacrifice is not found “only” in a political struggle or in a battle for freedom, as praiseworthy as these goals may be; rather, it represents a reference to the sacrifice of Christ, who gave His life for his disciples.

Together, these beautiful pieces bear witness to Liszt’s incredible expressive power, to his mastery of the pianistic language and technique, and to his ability to touch the souls of his listeners, in the twenty-first century as at the time of their creation.