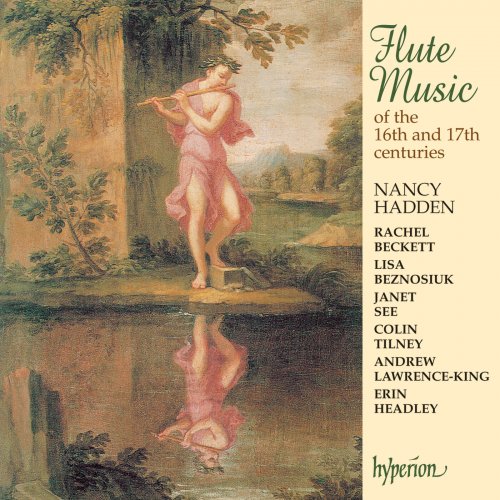

Nancy Hadden - Flute Music of the 16th & 17th Centuries (1989)

BAND/ARTIST: Nancy Hadden

- Title: Flute Music of the 16th & 17th Centuries

- Year Of Release: 1989

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical Flute

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:01:58

- Total Size: 234 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Cancion francesa glosada

02. Diferencias sobra "O felici occhi miei"

03. Was wird es doch des wunders noch

04. Ach Lieb mit Leid

05. Taundernaken

06. O passi sparsi

07. De vous servir

08. En espoir d'avoir mieulx

09. Elle veult donc

10. Ancor che col partire

11. Ung gay bergier

12. Bransle de Champaigne / Bransle de Poictou

13. Content desir a 3

14. Or vien ça

15. Onder te linde groene

16. Doen Dafne over de schoene maeght

17. Amarilli mia bella

18. Canzona

19. Canzona quarta a due, conto e basso

20. Toccata ottava, Libro Primo

21. Sonata prima per soprano solo

22. Passacaglio in G Minor

The transverse flute of the Renaissance and early Baroque periods was keyless and had a narrow cylindrical bore and subtle external tapering. Trebles and tenors were made in one piece; basses were usually jointed below the mouth hole, reinforced with a delicate metal ring. An instrument of simplicity and grace, this flute is like the new moon, mesmerizing and enchanting in its simple beauty, but with a great deal more to it than appears on the cool, clear surface. Surviving instruments, especially those in the Accademia Filarmonica in Verona, show that the finest craftsmen made instruments whose sound production was flexible enough to allow the player a great deal of control over tone-colour and intonation, the latter posing not inconsiderable difficulties. The player can produce a sound whose vocal quality has both a singing delicacy and dynamic flexibility. Perhaps because of this, the flute was often played in ensemble with plucked and bowed string instruments, and with the voice. Judging from surviving inventories, paintings, treatises, and accounts of performances, the instrument was popular throughout Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. There is a surprising and rewarding amount of solo and consort repertoire which was drawn upon for this recording.

In 1533 Pierre Attaingnant published two collections of music for a consort of four transverse flutes or recorders. The flute pieces he denoted with the letter ‘a’, those for recorder with ‘b’, and some for both with ‘ab’. The music is by leading composers of the time, including Claudin de Sermisy, Clement Janequin, Nicolas Gombert and Sebastiano Festa. In Germany, the title page of a songbook published by Arnt von Aich in 1518 reads: ‘Joyful for singing, some are suitable also for recorders, flutes and similar musical instruments.’ In the 1554 edition of Georg Förster’s Frisch teutsch Liedlein, margin notes specify some pieces for transverse flute.

Most sources describe three sizes of flutes – treble, tenor and bass; the tenor with its range of over two octaves from d1 being the most versatile. Flutes played together in various combinations, but matching instruments to music is not straightforward. Various transpositions are necessary, and indeed even the pieces that Attaingnant published with flutes in mind require it. Transposition practices for the flute are described in Musica instrumentalis deudsch (1529 and 1545) by Martin Agricola. He is also the first, but not the only source to describe the use of vibrato (‘zitterndem winde’) on the transverse flute.

While there are many paintings and references to flute-playing in sixteenth-century Italy, no specific music for the flute survives from Italian sources before about 1600. But the instrument is described in treatises and diminution manuals where it is called variously ‘traversa’, ‘fiffaro’, ‘piffaro’. For example, Aurelio Virgiliano’s Il Dolcimelo (c1600) contains several ricercari for ‘traversa’, and the title page of Antonio Brunelli’s Varii esercitii (1614) reads: ‘… per esercition di cornetti, traverse, flauti, viole, violine …’

In the early seventeenth century the Italian church musician Giovanni Battista Riccio published several canzonas for recorder in his Divine lodi musicali. Such works, as well as music for cornetto or violin, serve equally for the flute, particularly pieces of a sighing or melancholy nature, such as the beautiful Passacaglia by Marini and Castello’s Sonata for soprano solo.

The blind carillon player of Utrecht, Jacob van Eyck, published Der Fluyten Lust-hof in the 1640s, a collection of well known tunes with virtuoso divisions. Although these pieces are often played on the recorder today, van Eyck indicates their suitability for both the transverse flute and recorder by illustrating both instruments in his preface.

The cylindrical flute continued in use right through to the late seventeenth century when it coexisted for a while with the newly developing Baroque flute. But the two instruments have little in common. The design of the Baroque flute is completely different: it is jointed, with ornate turnings at the sockets, and its conical bore, thicker walls and larger embouchure hole dramatically alter the tone quality and response. A single key was added to facilitate the E flat, before obtainable only by shading the bottom hole with the finger. The Baroque instrument favours the dark low register, while the ‘Renaissance’ flute is happiest in its brighter top octave. One has only to see and hear the French Baroque flutes of Hotteterre to understand the artistic impact and importance of the redesign of the flute in the 1670s, when the neo-Platonic soprano gave way to the visually and tonally complex alto voice of the French taste.

01. Cancion francesa glosada

02. Diferencias sobra "O felici occhi miei"

03. Was wird es doch des wunders noch

04. Ach Lieb mit Leid

05. Taundernaken

06. O passi sparsi

07. De vous servir

08. En espoir d'avoir mieulx

09. Elle veult donc

10. Ancor che col partire

11. Ung gay bergier

12. Bransle de Champaigne / Bransle de Poictou

13. Content desir a 3

14. Or vien ça

15. Onder te linde groene

16. Doen Dafne over de schoene maeght

17. Amarilli mia bella

18. Canzona

19. Canzona quarta a due, conto e basso

20. Toccata ottava, Libro Primo

21. Sonata prima per soprano solo

22. Passacaglio in G Minor

The transverse flute of the Renaissance and early Baroque periods was keyless and had a narrow cylindrical bore and subtle external tapering. Trebles and tenors were made in one piece; basses were usually jointed below the mouth hole, reinforced with a delicate metal ring. An instrument of simplicity and grace, this flute is like the new moon, mesmerizing and enchanting in its simple beauty, but with a great deal more to it than appears on the cool, clear surface. Surviving instruments, especially those in the Accademia Filarmonica in Verona, show that the finest craftsmen made instruments whose sound production was flexible enough to allow the player a great deal of control over tone-colour and intonation, the latter posing not inconsiderable difficulties. The player can produce a sound whose vocal quality has both a singing delicacy and dynamic flexibility. Perhaps because of this, the flute was often played in ensemble with plucked and bowed string instruments, and with the voice. Judging from surviving inventories, paintings, treatises, and accounts of performances, the instrument was popular throughout Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. There is a surprising and rewarding amount of solo and consort repertoire which was drawn upon for this recording.

In 1533 Pierre Attaingnant published two collections of music for a consort of four transverse flutes or recorders. The flute pieces he denoted with the letter ‘a’, those for recorder with ‘b’, and some for both with ‘ab’. The music is by leading composers of the time, including Claudin de Sermisy, Clement Janequin, Nicolas Gombert and Sebastiano Festa. In Germany, the title page of a songbook published by Arnt von Aich in 1518 reads: ‘Joyful for singing, some are suitable also for recorders, flutes and similar musical instruments.’ In the 1554 edition of Georg Förster’s Frisch teutsch Liedlein, margin notes specify some pieces for transverse flute.

Most sources describe three sizes of flutes – treble, tenor and bass; the tenor with its range of over two octaves from d1 being the most versatile. Flutes played together in various combinations, but matching instruments to music is not straightforward. Various transpositions are necessary, and indeed even the pieces that Attaingnant published with flutes in mind require it. Transposition practices for the flute are described in Musica instrumentalis deudsch (1529 and 1545) by Martin Agricola. He is also the first, but not the only source to describe the use of vibrato (‘zitterndem winde’) on the transverse flute.

While there are many paintings and references to flute-playing in sixteenth-century Italy, no specific music for the flute survives from Italian sources before about 1600. But the instrument is described in treatises and diminution manuals where it is called variously ‘traversa’, ‘fiffaro’, ‘piffaro’. For example, Aurelio Virgiliano’s Il Dolcimelo (c1600) contains several ricercari for ‘traversa’, and the title page of Antonio Brunelli’s Varii esercitii (1614) reads: ‘… per esercition di cornetti, traverse, flauti, viole, violine …’

In the early seventeenth century the Italian church musician Giovanni Battista Riccio published several canzonas for recorder in his Divine lodi musicali. Such works, as well as music for cornetto or violin, serve equally for the flute, particularly pieces of a sighing or melancholy nature, such as the beautiful Passacaglia by Marini and Castello’s Sonata for soprano solo.

The blind carillon player of Utrecht, Jacob van Eyck, published Der Fluyten Lust-hof in the 1640s, a collection of well known tunes with virtuoso divisions. Although these pieces are often played on the recorder today, van Eyck indicates their suitability for both the transverse flute and recorder by illustrating both instruments in his preface.

The cylindrical flute continued in use right through to the late seventeenth century when it coexisted for a while with the newly developing Baroque flute. But the two instruments have little in common. The design of the Baroque flute is completely different: it is jointed, with ornate turnings at the sockets, and its conical bore, thicker walls and larger embouchure hole dramatically alter the tone quality and response. A single key was added to facilitate the E flat, before obtainable only by shading the bottom hole with the finger. The Baroque instrument favours the dark low register, while the ‘Renaissance’ flute is happiest in its brighter top octave. One has only to see and hear the French Baroque flutes of Hotteterre to understand the artistic impact and importance of the redesign of the flute in the 1670s, when the neo-Platonic soprano gave way to the visually and tonally complex alto voice of the French taste.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads