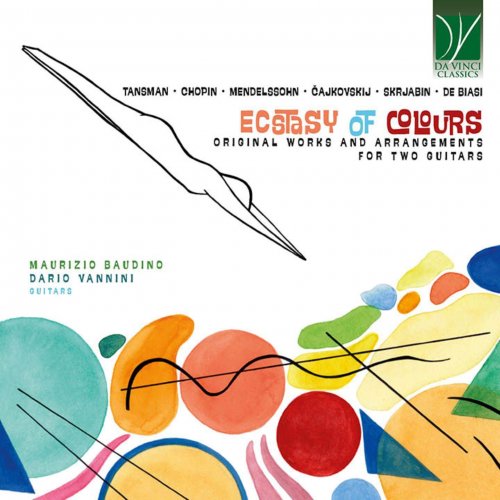

Maurizio Baudino, Dario Vannini - Ecstasy of Colours (2024)

BAND/ARTIST: Maurizio Baudino, Dario Vannini

- Title: Ecstasy of Colours

- Year Of Release: 2024

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Guitar

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:55:31

- Total Size: 187 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Sonatine for Two Guitars: I. Moderé

02. Sonatine for Two Guitars: II. Elegia

03. Sonatine for Two Guitars: III. Vif

04. Sonatine for Two Guitars: IV. Fughetta

05. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 1, Mesto (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

06. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 2, Vivace (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

07. Romanza sin palabras No.20, Op. 53: No. 2, Endecha amorosa (Arrangement by Miguel Llobel)

08. Romanza sin palabras No.25, Op. 62: No. 1, Consolación (Arrangement by Miguel Llobel)

09. Deux Morceaux, Op. 10: No. 1, Nocturne (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

10. Deux Morceaux, Op. 10: No. 2, Humoresque (Arrangement by Miguel Llobel)

11. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 3, Semplice (Arrangement by J. Stockmann)

12. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 4 (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

13. Cinq préludes, Op. 16: I. Andante (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

14. Cinq préludes, Op. 16: II. Allegro (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

15. Cinq préludes, Op. 16: III. Andante cantabile (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

16. Cinq préludes, Op. 16: IV. Lento (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

17. Cinq préludes, Op. 16: V. Allegretto (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

18. Omaggio a Prokofiev, Op. 7

Over the course of his long concert career, Andrés Segovia (1891-1987) played many new compositions. Nevertheless, since his debut, he accompanied the execution of original pieces with the transcription of renowned pages by contemporary and past composers, especially J. S. Bach. In his second public concert program – no copy of the first one survived – we can find pieces by Tárrega, Chueca, and Malats, as well as transcriptions from Haydn, Beethoven, and Schubert. And so it was that, in the years to come, Segovia played pieces by Mozart, Bach, Händel, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Albéniz, and Granados, on a regular basis. The piano transcription was a distinguished feature of Maestros before him, e.g. Francisco Tárrega and Miguel Llobet. The less famous Jan Nepomucen Bobrowicz (1885-1881), a student of Mauro Giuliani, had already transcribed pieces for guitar a long time before, the popular Mazurkas Op. 6 and Op. 7 by Chopin. Among these, a jewel of the piano repertoire, a short page, the only one of this author selected by Segovia: the Prelude No. 4 of Op. 16 by Aleksandr Skrjabin, transcribed in 1945. It was not by chance: the vivid lyricism of this prelude – which flows through a unique and simple melodic line for the majority of the piece – its harmonic variety even in such a short space and its equivalent variety of colors were attractive to the musical sensibility of Segovia. After many years, in November 1970, the Spanish guitarist sent this very piece to his friend Alexandre Tansman, thus suggesting to use it as a theme for a cycle of variations: it was then published in 1972 under the title Variations sur un thème de Scriabine.

Tansman was born in Łódź on June 11th, 1897, and grew up in a family of musicians. His parents encouraged his early passion for music, a passion that arose when he was only six years old listening to Bach’s Chaconne. He later studied piano, harmony, and counterpoint. In 1919 he won the three first prizes at the National composition Competition, using three different pseudonyms and, thanks to the success achieved, he decided to move to Paris. Outraged by the collaborationism of the Polish government with Nazi Germany, in 1938 Tansman decided to renounce his Polish citizenship in favor of the French one. Because of the severe political situation, he had to migrate to Los Angeles with his family. He later came back to France, and died in Paris on November 15th, 19861. Most of his twenty-one compositions for guitar resulted from his friendship with Segovia. Only ten out of these were published when the author was still alive. The Sonatine, whose manuscript was partially found in the archives of the Spanish guitarist in Linares and partially in those of Olga Coelho in Brazil, never performed before as piece for solo guitar, was transcribed for two guitars by Angelo Gilardino (1941-2022).

Tansman and Segovia met in Paris in March, 1924, during a private concert of the Spanish guitarist at Henri Prunières’s house, the director’s of the Revue Musicale. The execution of the Chaconne, the reawakening of his childhood memories, the genuine admiration for the Andalusian guitarist, made Tansman propose composing a bright piece for guitar, a challenge that was enthusiastically accepted by Segovia. Since its very first execution on March 13th, 1925, the Mazurka reaped such a great public success that, after the publication from Schott (1926), the author made several arrangements. The choice of this musical form has been particularly relevant. Chopin was one the composers that Segovia usually performed during his concerts. Just like Tansman, even Fryderyk Chopin, after his early music studies in Poland, moved to Paris at a very young age, where he lived until his passing, teaching, composing, and performing. Through Chopin, Tansman got to know and to admire the musical folklore of his land of origin; as he once declared: “My talent is Polish, the French culture gave it a sense of measure […]. I aim to this marvelous synthesis of Polish sensibility filtered by French clarity and sense of measure, whose most remarkable fruit was Chopin”. Coming from an educated environment and having expanded the knowledge of classical music since he was a child, Tansman didn’t get to know firsthand about Polish folklore, but rather took them through Chopin’s mazurkas. This is the reason why all the references to Polish folklore we find in Tansman’s work actually reveal a connection with those of Chopin.

The Mazurka is a dance characterized by a rhythm in triple meter with a forceful accent on the second or third beat, usually consisting of two or four parts having eight bars, and each part is repeated. The four mazurkas in Op. 33 by Chopin were composed between 1837 and 1838 and in these four pieces we can recognize a lively dance – especially in the second one, and in some sections of the fourth – a nostalgic quality, the recollections of the Polish countryside and his childhood. As described by Hector Berlioz in an article in 1849:

It was usually around midnight that he finally abandoned himself, when the fancy-pants were gone, when the political topic of the moment had been sufficiently debated, when all the scandalmongers had exhausted their anecdotes, all the tricks had been revealed, all the treacheries had been consumed , only then, indulging to the mute demand of two clever eyes, he became a poet singing of Ossianic loves and heroes of his dreams, and the suffering of a far-away country, ever eager for victory and ever beaten.

The same lyricism can be found in two other musical forms of the romantic piano repertoire: the nocturne and the romance without words. Chopin’s contribution to the first ones was vast, while Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy dedicated himself mainly to the second ones. Prolific composer, conductor, pianist and organist, he wrote forty-eight short piano pieces in the period between 1829 and 1845 under the title Lieder ohne Worte, indicating their predominantly melodic character, as of music for voice and instrumental accompaniment, in which everything is present, except the word.

Miguel Llobet (1878-1938) transcribed for one or two guitars numerous piano pages. In particular two Lieder ohne Worte arranged for a duo: the second one of Op. 53 (1839-1841) and the first one of Op. 62 (1842-1844). Both transcriptions are published under the Spanish title “romanza sin palabras” with the addition of a subtitle: Endecha amorosa for the first one, Consolaçion for the second one. Among the chosen pieces that Llobet transcribed for a duo, a page for piano by the Russian composer Pëtr Il’ič Čajkovskij, the Humoresque is present. It forms a diptych for piano and comes after the Nocturne, in the 1871 edition.

The compositions of Aleksandr Skrjabin’s early period from 1887 to 1903 are often labelled as “late-Romantic,” displaying a direct correlation with Chopin. «I have the pleasure of telling you that I was born on the 25th of December», he proudly wrote, even if, according to the current calendar, his birthdate would be 6th of January2. After the death of his mother, it was his aunt that looked after baby Aleksandr and arranged for his musical education. At a very young age, he played for Anton Rubinstein, who confirmed the boy’s natural talent, «perfect pitch, exceptional memory, [and] outstanding ability to imitate anything by ear». In the spring after his graduation in 1882, Boris Jurgenson offered to publish fourteen of Skrjabin’s already composed pieces. Even if Skrjabin was not paid for these publications, they contributed to his growing reputation. As a result, another publisher, Mitrofan Belaieff, offered him not only a payment for his publications, but a monthly salary as well. The compositions that were completed under the watchful eye of Belaieff include the five Preludes Op. 16. These works were the product of Skrjabin’s own creativity, but many of them may not have reached completion without Belaieff, who often encouraged Skrjabin to finish his compositions. His mood swings were unpredictable. To put it in his own words: «Suddenly it feels like my strength is unlimited, the world is my oyster. But straight after, I become aware of my utter helplessness. A sense of weariness and apathy overtakes my body. There is no balance in me».

Belaieff may have presumably arranged the trip to Europe in May 1895 in order to provide Skrjabin with specialist assessment and treatment. «Such a blackness in my life. The doctors have not yet given their verdict. Never before has a state of uncertainty been such torture for me. Oh, if only I could see some light ahead». He vented his feelings in a letter to Natalya Sekerina, a fifteen-years-old pianist with whom he madly fell in love. Her family disapproved their relationship, nevertheless Aleksandr tried to meet her again and again: «Don’t deprive me of my muse. Natalya creates my emotions, and I create the music.» Skrjabin’s psychological issues during these years may have contributed to the dark, agitated and melancholic tone of such compositions.

Out of those hard times, his interest towards mysticism, philosophy and symbolisms arose, and his personal vision of the art of the future, dreaming of a “unification of mankind in a single instant of ecstatic revelation”, came to light. A unification of men and art, a complete sensory, synesthetic, and spiritual experience. Prométhée: The Poem of Fire was composed in 1910. The cover of the score was a painting by his friend and painter Jean Delville: «Prometheus is situated in the center of a lyre (symbol and instrument of cosmic harmony) that links the sun (pre-eminently divine element) with the heart (human home) with its seven strings (symbol of the planets). Prometheus stole the fire from the gods and for this reason he let the human race progress alone, slipping away from the divine, but, for this reason, linking his life closely to the earth. Probably, is not difficult to believe that Skrjabin would see the new Promethean action through which human race could perceive the metaphysical world, made of sounds and colors (the Devachan) in his work, even if humans hadn’t developed their spiritual organs». These are the words of the guitarist, composer and painter Marco De Biasi from his Breve storia del rapporto suono e colore3. His Omaggio a Prokofiev is a sonata for two guitars in a single quadripartite movement. As in all other tributes, here too De Biasi mixes thematic and personal rhythmic patterns with stylistic elements that can be traced back to Prokofiev’s poetics, without necessarily having to resort to stylistic elements of the dedicatory composer. In this way the work does not lose originality and identity, creating a bridge between temporal dimensions distant from each other. This music also fits into the research of the relationship between sound and color developed by the composer. In fact, there are melodic and chordal elements that derive directly from the use of scales and phono-chromatic chords, as theorized in his Armonia fonocromatica ipertonale.

01. Sonatine for Two Guitars: I. Moderé

02. Sonatine for Two Guitars: II. Elegia

03. Sonatine for Two Guitars: III. Vif

04. Sonatine for Two Guitars: IV. Fughetta

05. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 1, Mesto (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

06. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 2, Vivace (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

07. Romanza sin palabras No.20, Op. 53: No. 2, Endecha amorosa (Arrangement by Miguel Llobel)

08. Romanza sin palabras No.25, Op. 62: No. 1, Consolación (Arrangement by Miguel Llobel)

09. Deux Morceaux, Op. 10: No. 1, Nocturne (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

10. Deux Morceaux, Op. 10: No. 2, Humoresque (Arrangement by Miguel Llobel)

11. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 3, Semplice (Arrangement by J. Stockmann)

12. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 4 (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

13. Cinq préludes, Op. 16: I. Andante (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

14. Cinq préludes, Op. 16: II. Allegro (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

15. Cinq préludes, Op. 16: III. Andante cantabile (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

16. Cinq préludes, Op. 16: IV. Lento (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

17. Cinq préludes, Op. 16: V. Allegretto (Arrangement by Maurizio Baudino)

18. Omaggio a Prokofiev, Op. 7

Over the course of his long concert career, Andrés Segovia (1891-1987) played many new compositions. Nevertheless, since his debut, he accompanied the execution of original pieces with the transcription of renowned pages by contemporary and past composers, especially J. S. Bach. In his second public concert program – no copy of the first one survived – we can find pieces by Tárrega, Chueca, and Malats, as well as transcriptions from Haydn, Beethoven, and Schubert. And so it was that, in the years to come, Segovia played pieces by Mozart, Bach, Händel, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Albéniz, and Granados, on a regular basis. The piano transcription was a distinguished feature of Maestros before him, e.g. Francisco Tárrega and Miguel Llobet. The less famous Jan Nepomucen Bobrowicz (1885-1881), a student of Mauro Giuliani, had already transcribed pieces for guitar a long time before, the popular Mazurkas Op. 6 and Op. 7 by Chopin. Among these, a jewel of the piano repertoire, a short page, the only one of this author selected by Segovia: the Prelude No. 4 of Op. 16 by Aleksandr Skrjabin, transcribed in 1945. It was not by chance: the vivid lyricism of this prelude – which flows through a unique and simple melodic line for the majority of the piece – its harmonic variety even in such a short space and its equivalent variety of colors were attractive to the musical sensibility of Segovia. After many years, in November 1970, the Spanish guitarist sent this very piece to his friend Alexandre Tansman, thus suggesting to use it as a theme for a cycle of variations: it was then published in 1972 under the title Variations sur un thème de Scriabine.

Tansman was born in Łódź on June 11th, 1897, and grew up in a family of musicians. His parents encouraged his early passion for music, a passion that arose when he was only six years old listening to Bach’s Chaconne. He later studied piano, harmony, and counterpoint. In 1919 he won the three first prizes at the National composition Competition, using three different pseudonyms and, thanks to the success achieved, he decided to move to Paris. Outraged by the collaborationism of the Polish government with Nazi Germany, in 1938 Tansman decided to renounce his Polish citizenship in favor of the French one. Because of the severe political situation, he had to migrate to Los Angeles with his family. He later came back to France, and died in Paris on November 15th, 19861. Most of his twenty-one compositions for guitar resulted from his friendship with Segovia. Only ten out of these were published when the author was still alive. The Sonatine, whose manuscript was partially found in the archives of the Spanish guitarist in Linares and partially in those of Olga Coelho in Brazil, never performed before as piece for solo guitar, was transcribed for two guitars by Angelo Gilardino (1941-2022).

Tansman and Segovia met in Paris in March, 1924, during a private concert of the Spanish guitarist at Henri Prunières’s house, the director’s of the Revue Musicale. The execution of the Chaconne, the reawakening of his childhood memories, the genuine admiration for the Andalusian guitarist, made Tansman propose composing a bright piece for guitar, a challenge that was enthusiastically accepted by Segovia. Since its very first execution on March 13th, 1925, the Mazurka reaped such a great public success that, after the publication from Schott (1926), the author made several arrangements. The choice of this musical form has been particularly relevant. Chopin was one the composers that Segovia usually performed during his concerts. Just like Tansman, even Fryderyk Chopin, after his early music studies in Poland, moved to Paris at a very young age, where he lived until his passing, teaching, composing, and performing. Through Chopin, Tansman got to know and to admire the musical folklore of his land of origin; as he once declared: “My talent is Polish, the French culture gave it a sense of measure […]. I aim to this marvelous synthesis of Polish sensibility filtered by French clarity and sense of measure, whose most remarkable fruit was Chopin”. Coming from an educated environment and having expanded the knowledge of classical music since he was a child, Tansman didn’t get to know firsthand about Polish folklore, but rather took them through Chopin’s mazurkas. This is the reason why all the references to Polish folklore we find in Tansman’s work actually reveal a connection with those of Chopin.

The Mazurka is a dance characterized by a rhythm in triple meter with a forceful accent on the second or third beat, usually consisting of two or four parts having eight bars, and each part is repeated. The four mazurkas in Op. 33 by Chopin were composed between 1837 and 1838 and in these four pieces we can recognize a lively dance – especially in the second one, and in some sections of the fourth – a nostalgic quality, the recollections of the Polish countryside and his childhood. As described by Hector Berlioz in an article in 1849:

It was usually around midnight that he finally abandoned himself, when the fancy-pants were gone, when the political topic of the moment had been sufficiently debated, when all the scandalmongers had exhausted their anecdotes, all the tricks had been revealed, all the treacheries had been consumed , only then, indulging to the mute demand of two clever eyes, he became a poet singing of Ossianic loves and heroes of his dreams, and the suffering of a far-away country, ever eager for victory and ever beaten.

The same lyricism can be found in two other musical forms of the romantic piano repertoire: the nocturne and the romance without words. Chopin’s contribution to the first ones was vast, while Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy dedicated himself mainly to the second ones. Prolific composer, conductor, pianist and organist, he wrote forty-eight short piano pieces in the period between 1829 and 1845 under the title Lieder ohne Worte, indicating their predominantly melodic character, as of music for voice and instrumental accompaniment, in which everything is present, except the word.

Miguel Llobet (1878-1938) transcribed for one or two guitars numerous piano pages. In particular two Lieder ohne Worte arranged for a duo: the second one of Op. 53 (1839-1841) and the first one of Op. 62 (1842-1844). Both transcriptions are published under the Spanish title “romanza sin palabras” with the addition of a subtitle: Endecha amorosa for the first one, Consolaçion for the second one. Among the chosen pieces that Llobet transcribed for a duo, a page for piano by the Russian composer Pëtr Il’ič Čajkovskij, the Humoresque is present. It forms a diptych for piano and comes after the Nocturne, in the 1871 edition.

The compositions of Aleksandr Skrjabin’s early period from 1887 to 1903 are often labelled as “late-Romantic,” displaying a direct correlation with Chopin. «I have the pleasure of telling you that I was born on the 25th of December», he proudly wrote, even if, according to the current calendar, his birthdate would be 6th of January2. After the death of his mother, it was his aunt that looked after baby Aleksandr and arranged for his musical education. At a very young age, he played for Anton Rubinstein, who confirmed the boy’s natural talent, «perfect pitch, exceptional memory, [and] outstanding ability to imitate anything by ear». In the spring after his graduation in 1882, Boris Jurgenson offered to publish fourteen of Skrjabin’s already composed pieces. Even if Skrjabin was not paid for these publications, they contributed to his growing reputation. As a result, another publisher, Mitrofan Belaieff, offered him not only a payment for his publications, but a monthly salary as well. The compositions that were completed under the watchful eye of Belaieff include the five Preludes Op. 16. These works were the product of Skrjabin’s own creativity, but many of them may not have reached completion without Belaieff, who often encouraged Skrjabin to finish his compositions. His mood swings were unpredictable. To put it in his own words: «Suddenly it feels like my strength is unlimited, the world is my oyster. But straight after, I become aware of my utter helplessness. A sense of weariness and apathy overtakes my body. There is no balance in me».

Belaieff may have presumably arranged the trip to Europe in May 1895 in order to provide Skrjabin with specialist assessment and treatment. «Such a blackness in my life. The doctors have not yet given their verdict. Never before has a state of uncertainty been such torture for me. Oh, if only I could see some light ahead». He vented his feelings in a letter to Natalya Sekerina, a fifteen-years-old pianist with whom he madly fell in love. Her family disapproved their relationship, nevertheless Aleksandr tried to meet her again and again: «Don’t deprive me of my muse. Natalya creates my emotions, and I create the music.» Skrjabin’s psychological issues during these years may have contributed to the dark, agitated and melancholic tone of such compositions.

Out of those hard times, his interest towards mysticism, philosophy and symbolisms arose, and his personal vision of the art of the future, dreaming of a “unification of mankind in a single instant of ecstatic revelation”, came to light. A unification of men and art, a complete sensory, synesthetic, and spiritual experience. Prométhée: The Poem of Fire was composed in 1910. The cover of the score was a painting by his friend and painter Jean Delville: «Prometheus is situated in the center of a lyre (symbol and instrument of cosmic harmony) that links the sun (pre-eminently divine element) with the heart (human home) with its seven strings (symbol of the planets). Prometheus stole the fire from the gods and for this reason he let the human race progress alone, slipping away from the divine, but, for this reason, linking his life closely to the earth. Probably, is not difficult to believe that Skrjabin would see the new Promethean action through which human race could perceive the metaphysical world, made of sounds and colors (the Devachan) in his work, even if humans hadn’t developed their spiritual organs». These are the words of the guitarist, composer and painter Marco De Biasi from his Breve storia del rapporto suono e colore3. His Omaggio a Prokofiev is a sonata for two guitars in a single quadripartite movement. As in all other tributes, here too De Biasi mixes thematic and personal rhythmic patterns with stylistic elements that can be traced back to Prokofiev’s poetics, without necessarily having to resort to stylistic elements of the dedicatory composer. In this way the work does not lose originality and identity, creating a bridge between temporal dimensions distant from each other. This music also fits into the research of the relationship between sound and color developed by the composer. In fact, there are melodic and chordal elements that derive directly from the use of scales and phono-chromatic chords, as theorized in his Armonia fonocromatica ipertonale.

Year 2024 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads