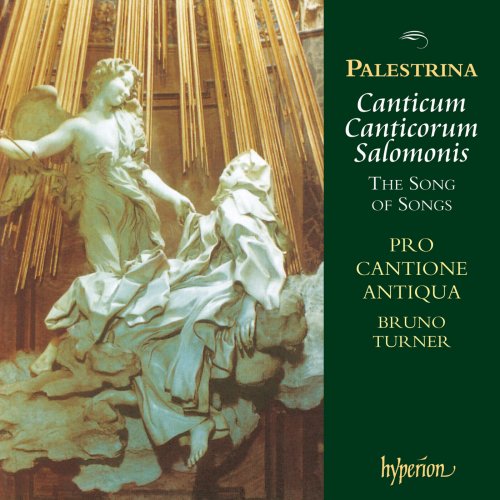

Pro Cantione Antiqua, Bruno Turner - Palestrina: Canticum Canticorum Salomonis - The Song of Songs (1994)

BAND/ARTIST: Pro Cantione Antiqua, Bruno Turner

- Title: Palestrina: Canticum Canticorum Salomonis - The Song of Songs

- Year Of Release: 1994

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:19:42

- Total Size: 329 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": I. Osculetur me osculo oris sui

02. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": II. Trahe me post te

03. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": III. Nigra sum sed formosa

04. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": IV. Vineam meam non custodivi

05. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": V. Si ignoras te, o pulchra

06. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": VI. Pulchrae sunt genae tuae

07. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": VII. Fasciculus myrrhae dilectus meus

08. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": VIII. Ecce tu pulcher es

09. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": IX. Tota pulchra es, amica mea

10. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": X. Vulnerasti cor meum

11. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XI. Sicut lilium inter spinas

12. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XII. Introduxit me Rex in cellam

13. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XIII. Laeva eius sub capite meo

14. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XIV. Vox dilecti mei

15. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XV. Surge, propera, amica mea

16. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XVI. Surge, amica mea, speciosa mea

17. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XVII. Dilectus meus mihi

18. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XVIII. Surgam et circuibo civitatem

19. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XIX. Adiuro vos, filiae Hierusalem

20. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XX. Caput eius aurum optimum

21. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXI. Dilectus meus descendit

22. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXII. Pulchra es amica mea

23. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXIII. Quae est ista quae progreditur

24. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXIV. Descendi in hortum meum

25. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXV. Quam pulchri sunt gressus tui

26. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXVI. Duo ubera tua

27. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXVII. Quam pulchra es, et quam decora

28. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXVIII. Guttur tuum sicut vinum optimum

29. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXIX. Veni, dilecte mi

‘There are far too many poems with no other subject than love of a kind quite alien to the Christian faith.’

In this way Palestrina began the dedication to Pope Gregory XIII of his Fourth Book of Motets. He continued with an apology that has seemed to some modern historians to be pure hypocrisy. The composer ‘blushed and grieved’ that he was one of those whose musical art had been lavished upon such love-poems and that he had been in company with those who were ruled by passion and corrupted by their youthfulness.

But this was not the first time that Palestrina had claimed to suffer a bad conscience about the use of his composer’s gifts in the service of ‘light and vain ideas’. Indeed, in 1569 at the age of about forty-four, he regarded himself as getting elderly and assured another of his dedicatees and his public that his gifts would henceforth be devoted to things ‘dignified and serious, worthy of a Christian soul’.

When in 1584 the Roman printer Alessandro Gardano brought out Motettorum Quinque Vocibus LIBER QUARTUS there was no mention on the title page that the contents were drawn entirely from what the Latin Bible calls Canticum Canticorum. In his dedication Palestrina follows his apology with this resolution: ‘But as what is past cannot be altered nor deeds undone, I have changed my purpose’. Recently, he explains, he had laboured upon poems ‘written of the praises of our Lord Jesus Christ and His most Holy Mother the Virgin Mary’ (a reference to his Madrigali spirituali of 1581), and now upon poems containing the divine love of Christ and His spouse the soul, indeed the ‘Songs of Solomon’ (Salomonis nimirum cantica). In the numerous later editions from 1587 to 1613, the title pages become more explicit, with phrases like motettorum ex canticis Salomonis or ex cantico canticarum (sic).

There are indications of haste in the first printing. The tenor and bass part-books are dated 1583, the other three 1584. There are a few obvious errors and omissions in this original set. We may assume publication early in 1584, perhaps to meet a special demand. For these are not thinly disguised erotic madrigals that happen to be in Latin, nor are they liturgical motets. They are exactly what Palestrina said they were, and precisely what suited the private and public devotional gatherings of people encouraged most notably by St Philip Neri, a man of extraordinary influence who had transformed religious and cultural life in Rome since the early 1560s. Under his persuasion confraternities were formed for the practice of spiritual exercises. Laudi spirituali were revived and madrigali spirituali became a popular musical genre. Indeed, Palestrina was a founder member of the Compagnia de i Musici di Roma dedicated to St Cecilia, begun in 1584. Bringing out his Song of Songs collection just in time may well have been Palestrina’s inaugural contribution.

By dedicating the set to his patron and employer Gregory XIII, Palestrina not only followed convention but honoured a reforming Pope who had supported him in his post as master of the Julian Chapel Choir, who had commissioned him (with Zoilo) to revise and reform the Roman chant books, and who had continued to keep Palestrina in his private chapel as an unofficial Papal composer.

There is every reason to believe that the earliest performances would have been by Palestrina’s small group of colleagues, adult male singers of the Papal choirs, the Julian in particular. Palestrina’s twenty-nine motets are vocal chamber music with a wide appeal that was recognized in his own time. The eleven editions in part-books are testimony to the popularity that Palestrina clearly expected. He may not have been a hypocrite but he was no fool in his business dealings or his publishing acumen. His Song of Songs was eminently suitable then, as it is now, for every kind of small singing group from male-voice soloists to mixed voices in small choirs, in low- or high-pitch performance.

Our modern age can hardly avoid some cynicism in regard to the traditional Jewish and Christian allegorical interpretation of the Song of Songs: the texts clearly evolved from the love poetry of desert people, from cult-mythology and tribal wedding songs. But the Songs must be seen, and the music heard, in the context of an age of Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation fervour, an age devoted by Roman authority to the triumph of the Virgin as well as her tenderness. The Spouse of the allegory is not only the Church or the individual soul but the bride who is represented by Our Lady the Mediator and by the Queen of Heaven, the One arrayed for battle, even the woman of the Apocalypse; certainly to Palestrina’s contemporaries, the Virgin who won the Battle of Lepanto (1571) and for whom the Papacy instituted the Feast of Our Lady of Victory. The gentle enclosed garden of Virginity is balanced by the Catholic vision of triumph over evil; in the words of the Spaniard, Luis de Leon: ‘Virgin, arrayed in the sun, crowned with eternal stars, who walks her sacred feet upon the moon’. Fray Luis wrote his poems in 1572 when he was imprisoned for translating the Canticum Canticorum into Spanish. St Teresa of Avila had to burn her Meditation on the Song of Songs. It seemed to the authorities that the allegory could be preserved in the Latin but that the eroticism would prevail in the vernacular.

Although some have thought to impose a story-line upon Palestrina’s twenty-nine motets, with a narrative continuum between Bride, Bridegroom and Chorus, there is little evidence that the composer has attempted this at all. He rarely even observes these exchanges, nor does he characterize or dramatize the persons or events. His selection and division of the texts ignores what we see in modern editions of the Bible. In fact Palestrina was working from the Latin Bible prior to the Biblia Vulgata revision of 1592. This also accounts for some variants in the Latin text as set by Palestrina. In this performance some ‘errors’ have been corrected, as they were in later editions in Palestrina’s time. Other variants have been retained just as they were in all the editions.

Finally, the present editor has adapted an early seventeenth-century English translation, hoping to preserve some of the allegorical aspect by the antiquity of the style, yet attempting to render into English what Palestrina would have understood by the Latin, not what modern Biblical scholarship has determined as the meaning of the original Hebrew and Greek sources. Palestrina was setting the Latin as he knew it, in the way that he and his Church understood it.

01. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": I. Osculetur me osculo oris sui

02. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": II. Trahe me post te

03. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": III. Nigra sum sed formosa

04. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": IV. Vineam meam non custodivi

05. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": V. Si ignoras te, o pulchra

06. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": VI. Pulchrae sunt genae tuae

07. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": VII. Fasciculus myrrhae dilectus meus

08. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": VIII. Ecce tu pulcher es

09. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": IX. Tota pulchra es, amica mea

10. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": X. Vulnerasti cor meum

11. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XI. Sicut lilium inter spinas

12. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XII. Introduxit me Rex in cellam

13. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XIII. Laeva eius sub capite meo

14. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XIV. Vox dilecti mei

15. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XV. Surge, propera, amica mea

16. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XVI. Surge, amica mea, speciosa mea

17. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XVII. Dilectus meus mihi

18. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XVIII. Surgam et circuibo civitatem

19. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XIX. Adiuro vos, filiae Hierusalem

20. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XX. Caput eius aurum optimum

21. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXI. Dilectus meus descendit

22. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXII. Pulchra es amica mea

23. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXIII. Quae est ista quae progreditur

24. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXIV. Descendi in hortum meum

25. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXV. Quam pulchri sunt gressus tui

26. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXVI. Duo ubera tua

27. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXVII. Quam pulchra es, et quam decora

28. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXVIII. Guttur tuum sicut vinum optimum

29. Canticum Canticorum "The Song of Songs": XXIX. Veni, dilecte mi

‘There are far too many poems with no other subject than love of a kind quite alien to the Christian faith.’

In this way Palestrina began the dedication to Pope Gregory XIII of his Fourth Book of Motets. He continued with an apology that has seemed to some modern historians to be pure hypocrisy. The composer ‘blushed and grieved’ that he was one of those whose musical art had been lavished upon such love-poems and that he had been in company with those who were ruled by passion and corrupted by their youthfulness.

But this was not the first time that Palestrina had claimed to suffer a bad conscience about the use of his composer’s gifts in the service of ‘light and vain ideas’. Indeed, in 1569 at the age of about forty-four, he regarded himself as getting elderly and assured another of his dedicatees and his public that his gifts would henceforth be devoted to things ‘dignified and serious, worthy of a Christian soul’.

When in 1584 the Roman printer Alessandro Gardano brought out Motettorum Quinque Vocibus LIBER QUARTUS there was no mention on the title page that the contents were drawn entirely from what the Latin Bible calls Canticum Canticorum. In his dedication Palestrina follows his apology with this resolution: ‘But as what is past cannot be altered nor deeds undone, I have changed my purpose’. Recently, he explains, he had laboured upon poems ‘written of the praises of our Lord Jesus Christ and His most Holy Mother the Virgin Mary’ (a reference to his Madrigali spirituali of 1581), and now upon poems containing the divine love of Christ and His spouse the soul, indeed the ‘Songs of Solomon’ (Salomonis nimirum cantica). In the numerous later editions from 1587 to 1613, the title pages become more explicit, with phrases like motettorum ex canticis Salomonis or ex cantico canticarum (sic).

There are indications of haste in the first printing. The tenor and bass part-books are dated 1583, the other three 1584. There are a few obvious errors and omissions in this original set. We may assume publication early in 1584, perhaps to meet a special demand. For these are not thinly disguised erotic madrigals that happen to be in Latin, nor are they liturgical motets. They are exactly what Palestrina said they were, and precisely what suited the private and public devotional gatherings of people encouraged most notably by St Philip Neri, a man of extraordinary influence who had transformed religious and cultural life in Rome since the early 1560s. Under his persuasion confraternities were formed for the practice of spiritual exercises. Laudi spirituali were revived and madrigali spirituali became a popular musical genre. Indeed, Palestrina was a founder member of the Compagnia de i Musici di Roma dedicated to St Cecilia, begun in 1584. Bringing out his Song of Songs collection just in time may well have been Palestrina’s inaugural contribution.

By dedicating the set to his patron and employer Gregory XIII, Palestrina not only followed convention but honoured a reforming Pope who had supported him in his post as master of the Julian Chapel Choir, who had commissioned him (with Zoilo) to revise and reform the Roman chant books, and who had continued to keep Palestrina in his private chapel as an unofficial Papal composer.

There is every reason to believe that the earliest performances would have been by Palestrina’s small group of colleagues, adult male singers of the Papal choirs, the Julian in particular. Palestrina’s twenty-nine motets are vocal chamber music with a wide appeal that was recognized in his own time. The eleven editions in part-books are testimony to the popularity that Palestrina clearly expected. He may not have been a hypocrite but he was no fool in his business dealings or his publishing acumen. His Song of Songs was eminently suitable then, as it is now, for every kind of small singing group from male-voice soloists to mixed voices in small choirs, in low- or high-pitch performance.

Our modern age can hardly avoid some cynicism in regard to the traditional Jewish and Christian allegorical interpretation of the Song of Songs: the texts clearly evolved from the love poetry of desert people, from cult-mythology and tribal wedding songs. But the Songs must be seen, and the music heard, in the context of an age of Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation fervour, an age devoted by Roman authority to the triumph of the Virgin as well as her tenderness. The Spouse of the allegory is not only the Church or the individual soul but the bride who is represented by Our Lady the Mediator and by the Queen of Heaven, the One arrayed for battle, even the woman of the Apocalypse; certainly to Palestrina’s contemporaries, the Virgin who won the Battle of Lepanto (1571) and for whom the Papacy instituted the Feast of Our Lady of Victory. The gentle enclosed garden of Virginity is balanced by the Catholic vision of triumph over evil; in the words of the Spaniard, Luis de Leon: ‘Virgin, arrayed in the sun, crowned with eternal stars, who walks her sacred feet upon the moon’. Fray Luis wrote his poems in 1572 when he was imprisoned for translating the Canticum Canticorum into Spanish. St Teresa of Avila had to burn her Meditation on the Song of Songs. It seemed to the authorities that the allegory could be preserved in the Latin but that the eroticism would prevail in the vernacular.

Although some have thought to impose a story-line upon Palestrina’s twenty-nine motets, with a narrative continuum between Bride, Bridegroom and Chorus, there is little evidence that the composer has attempted this at all. He rarely even observes these exchanges, nor does he characterize or dramatize the persons or events. His selection and division of the texts ignores what we see in modern editions of the Bible. In fact Palestrina was working from the Latin Bible prior to the Biblia Vulgata revision of 1592. This also accounts for some variants in the Latin text as set by Palestrina. In this performance some ‘errors’ have been corrected, as they were in later editions in Palestrina’s time. Other variants have been retained just as they were in all the editions.

Finally, the present editor has adapted an early seventeenth-century English translation, hoping to preserve some of the allegorical aspect by the antiquity of the style, yet attempting to render into English what Palestrina would have understood by the Latin, not what modern Biblical scholarship has determined as the meaning of the original Hebrew and Greek sources. Palestrina was setting the Latin as he knew it, in the way that he and his Church understood it.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads