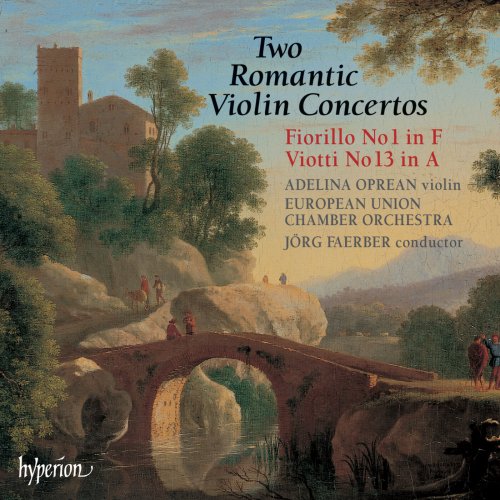

Adelina Oprean, European Union Chamber Orchestra, Jörg Faerber - Fiorillo: Violin Concerto No. 1 - Viotti: Violin Concerto No. 13 (1987)

BAND/ARTIST: Adelina Oprean, European Union Chamber Orchestra, Jörg Faerber

- Title: Fiorillo: Violin Concerto No. 1 - Viotti: Violin Concerto No. 13

- Year Of Release: 1987

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 00:46:27

- Total Size: 199 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Violin Concerto No. 1 in F Major: I. Allegro moderato

02. Violin Concerto No. 1 in F Major: II. Larghetto

03. Violin Concerto No. 1 in F Major: III. Rondo. Poco vivace

04. Violin Concerto No. 13 in A Major, WI:13: I. Allegro brillante

05. Violin Concerto No. 13 in A Major, WI:13: II. Andante

06. Violin Concerto No. 13 in A Major, WI:13: III. Tempo di minuetto

The eighteenth century was the first great age of the travelling virtuoso, with violinists—particularly Italian violinists—leading the way. Early in the century, such virtuosi as Geminiani, Veracini and Locatelli spent much of their lives outside Italy, followed later by Giardini, Lolli, Giornovichi, and many others. They sacrificed the relative security of an Italian court post or opera orchestra position for the prospect of fame and fortune in the capitals of northern Europe—alluring cities like Paris, London or St Petersburg. They might settle for many years in one place, especially if lucrative aristocratic patronage was forthcoming, or they might prefer to keep on the move on something like a modern concert tour.

It was a precarious lifestyle. There was plenty of opportunity for financial disaster, especially if the violinist dabbled in risky operatic ventures. He was subject to the approval of his patrons and to the whims of fashion, not to speak of political upheavals—Viotti was among many who fled to London from the turbulent Paris of the early 1790s. However, a virtuoso of European reputation could with judgment and a little luck be assured of a more than comfortable living in the north, perhaps eventually retiring to his homeland with the spoils of his success.

Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755–1824) was one of the last to follow this lucrative trail. (With the dazzling exception of Paganini, the nineteenth century proved a lean period for the Italian violin school.) He studied with Pugnani in Turin, and after five years in the Royal Chapel orchestra he joined his teacher on an ambitious European tour. They visited Dresden, Berlin, Warsaw and St Petersburg, with Viotti styling himself ‘pupil of the celebrated Pugnani’. His Paris debut, however, proved a turning-point—a concerto performance at the prestigious Concert Spirituel on 17 March 1782 caused a sensation. Critics remarked on his extraordinary power and technical precision, but it was his expressive and sonorous adagio playing that impressed most. Viotti was immediately hailed as the finest violinist in Europe.

Thus began a decade in Paris of immense importance to violin-playing. Viotti’s grand style, blending a bolder brilliance with a more serious and intense expression, marked a move away from decorative rococo elegance. Both his performances and his music influenced a whole generation of violinists—Rode, Baillot, Kreutzer, to name a few—and even Beethoven shows an awareness of Viotti’s style in his own violin concerto. This was also a period of changes in the instrument itself, as makers responded to the demand for more volume and for richer expressive resources. The 1780s saw in particular the perfecting of the modern bow by François Tourte—a development with which Viotti has traditionally been linked. Although his exact role remains unclear, the association is in itself some indication of his reputation.

Only eighteen months after his Paris debut, Viotti retired from public performance there—in 1784 he was appointed to the service of Marie Antoinette at Versailles, and later he went into opera promotion, an undertaking accompanied with unusual success. He continued, however, to compose violin concertos, completing nineteen before he left for London. No 13, published in 1788, was probably written for Versailles. The remaining ten concertos date from his London years—among them the celebrated No 22 which that stern critic Brahms described as ‘masterly’ and a particular favourite of his.

A more shadowy figure, and certainly a less influential one, was Viotti’s exact contemporary Federigo Fiorillo (1755–after 1823). Though he was born in Germany and at first preferred the mandolin, Fiorillo’s later career as a violin virtuoso closely resembled that of Viotti. First there was an extended tour, taking in St Petersburg, Poland, and Riga; then in 1785 he made his Paris debut, before settling in London three years later. Like Viotti, Fiorillo composed a great deal of violin music, including the 36 Caprices well-known to students today. His four concertos are much less familiar; the first was published in Paris in 1789.

We are indeed fortunate that so many violin concertos of this period survive at all. Virtuosos, who generally played their own compositions, guarded them jealously, carrying around sets of manuscript parts with them; most of these are now lost. However, this natural prudence competed with a strong commercial interest: the music-publishing business was rapidly expanding, and violinists seized the opportunity to have their music printed. Catalogues of the time do contain a large amount of domestic piano music and songs, including trivia like The Battle of Prague with its cannon-fire and cries of the wounded. But publishers also found room for such major concert works as Haydn’s symphonies and, more surprisingly, for the most virtuosic concertos. Much of this repertoire presented hair-raising technical difficulties, at least in pre-Paganini terms; had Mozart’s violin concertos been published during his lifetime, they would have stood out as technically quite undemanding. It is difficult to imagine gentleman amateurs making much of these taxing concertos, but the fact that they bought them has certainly ensured their survival. Paris publishers were particularly prolific in this area; in London, violin concertos often appeared in more saleable arrangements for piano.

Both Viotti and Fiorillo typically attempt to capture the attention by a mixture of brilliant virtuosity with expressiveness and melodic appeal. Fiorillo’s solo entry not only decorates the initial orchestral idea but also carries it into the higher reaches of the E string. Viotti finds an even more arresting gesture, the violinist entering unaccompanied with an assertive version of the opening bass line; he also selects the E string, but soon transfers the idea down to the G string, a favourite timbre which Viotti did much to popularise. The two first movements follow a broadly similar course; both set off bravura display with contrasting melodic paragraphs, including a lyrical second subject and a more passionate minor-key episode. Viotti explores minor keys further in the development sections, with signs of the drama and turbulence to come in his later concertos; and it is perhaps significant of his serious approach to the concerto form, and his disdain of technical display for its own sake, that he does not even give the traditional opportunity for a cadenza.

The slow movement was usually either a graceful French romance, with its regular melody and easily-grasped structure, or a long-breathed expressive cantilena. Fiorillo’s Larghetto has something of the romance character about it, though the charming melody is more than a little reminiscent of Mozart. Viotti was by this date moving away from standard types, and his Andante, while retaining a simple design, is more concerned with the noble cantabile natural to the Tourte bow; the warm sonority of the movement stems directly from the sound of the horns.

Last movements were by this date almost universally rondos, featuring a recurring melody with some characteristic rhythm. Fiorillo finds a catchy tune in 2/4 time, which alternates with extrovertly showy episodes; one of these makes striking use of the horns in dialogue with the soloist, an unusual idea at a time when the wind instruments were often regarded as optional. Viotti prefers the triple time of the minuet—yet this is no stately court dance but rather a jaunty polonaise. Piquant national tunes were common enough as rondo themes, but this particular movement created a fashion for the polonaise finale; and, in a curious reversal of the norm, the melody itself became highly popular as a song. Again the episodes contain some brilliant passagework (one idea is a flashy combination of trill and dotted rhythm), but Fiorillo finds time once more for a minor-key contrast. There is one final surprise—the last time the rondo theme recurs it is heard in the orchestra, accompanied now by that distinctive figure in the solo violin part.

01. Violin Concerto No. 1 in F Major: I. Allegro moderato

02. Violin Concerto No. 1 in F Major: II. Larghetto

03. Violin Concerto No. 1 in F Major: III. Rondo. Poco vivace

04. Violin Concerto No. 13 in A Major, WI:13: I. Allegro brillante

05. Violin Concerto No. 13 in A Major, WI:13: II. Andante

06. Violin Concerto No. 13 in A Major, WI:13: III. Tempo di minuetto

The eighteenth century was the first great age of the travelling virtuoso, with violinists—particularly Italian violinists—leading the way. Early in the century, such virtuosi as Geminiani, Veracini and Locatelli spent much of their lives outside Italy, followed later by Giardini, Lolli, Giornovichi, and many others. They sacrificed the relative security of an Italian court post or opera orchestra position for the prospect of fame and fortune in the capitals of northern Europe—alluring cities like Paris, London or St Petersburg. They might settle for many years in one place, especially if lucrative aristocratic patronage was forthcoming, or they might prefer to keep on the move on something like a modern concert tour.

It was a precarious lifestyle. There was plenty of opportunity for financial disaster, especially if the violinist dabbled in risky operatic ventures. He was subject to the approval of his patrons and to the whims of fashion, not to speak of political upheavals—Viotti was among many who fled to London from the turbulent Paris of the early 1790s. However, a virtuoso of European reputation could with judgment and a little luck be assured of a more than comfortable living in the north, perhaps eventually retiring to his homeland with the spoils of his success.

Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755–1824) was one of the last to follow this lucrative trail. (With the dazzling exception of Paganini, the nineteenth century proved a lean period for the Italian violin school.) He studied with Pugnani in Turin, and after five years in the Royal Chapel orchestra he joined his teacher on an ambitious European tour. They visited Dresden, Berlin, Warsaw and St Petersburg, with Viotti styling himself ‘pupil of the celebrated Pugnani’. His Paris debut, however, proved a turning-point—a concerto performance at the prestigious Concert Spirituel on 17 March 1782 caused a sensation. Critics remarked on his extraordinary power and technical precision, but it was his expressive and sonorous adagio playing that impressed most. Viotti was immediately hailed as the finest violinist in Europe.

Thus began a decade in Paris of immense importance to violin-playing. Viotti’s grand style, blending a bolder brilliance with a more serious and intense expression, marked a move away from decorative rococo elegance. Both his performances and his music influenced a whole generation of violinists—Rode, Baillot, Kreutzer, to name a few—and even Beethoven shows an awareness of Viotti’s style in his own violin concerto. This was also a period of changes in the instrument itself, as makers responded to the demand for more volume and for richer expressive resources. The 1780s saw in particular the perfecting of the modern bow by François Tourte—a development with which Viotti has traditionally been linked. Although his exact role remains unclear, the association is in itself some indication of his reputation.

Only eighteen months after his Paris debut, Viotti retired from public performance there—in 1784 he was appointed to the service of Marie Antoinette at Versailles, and later he went into opera promotion, an undertaking accompanied with unusual success. He continued, however, to compose violin concertos, completing nineteen before he left for London. No 13, published in 1788, was probably written for Versailles. The remaining ten concertos date from his London years—among them the celebrated No 22 which that stern critic Brahms described as ‘masterly’ and a particular favourite of his.

A more shadowy figure, and certainly a less influential one, was Viotti’s exact contemporary Federigo Fiorillo (1755–after 1823). Though he was born in Germany and at first preferred the mandolin, Fiorillo’s later career as a violin virtuoso closely resembled that of Viotti. First there was an extended tour, taking in St Petersburg, Poland, and Riga; then in 1785 he made his Paris debut, before settling in London three years later. Like Viotti, Fiorillo composed a great deal of violin music, including the 36 Caprices well-known to students today. His four concertos are much less familiar; the first was published in Paris in 1789.

We are indeed fortunate that so many violin concertos of this period survive at all. Virtuosos, who generally played their own compositions, guarded them jealously, carrying around sets of manuscript parts with them; most of these are now lost. However, this natural prudence competed with a strong commercial interest: the music-publishing business was rapidly expanding, and violinists seized the opportunity to have their music printed. Catalogues of the time do contain a large amount of domestic piano music and songs, including trivia like The Battle of Prague with its cannon-fire and cries of the wounded. But publishers also found room for such major concert works as Haydn’s symphonies and, more surprisingly, for the most virtuosic concertos. Much of this repertoire presented hair-raising technical difficulties, at least in pre-Paganini terms; had Mozart’s violin concertos been published during his lifetime, they would have stood out as technically quite undemanding. It is difficult to imagine gentleman amateurs making much of these taxing concertos, but the fact that they bought them has certainly ensured their survival. Paris publishers were particularly prolific in this area; in London, violin concertos often appeared in more saleable arrangements for piano.

Both Viotti and Fiorillo typically attempt to capture the attention by a mixture of brilliant virtuosity with expressiveness and melodic appeal. Fiorillo’s solo entry not only decorates the initial orchestral idea but also carries it into the higher reaches of the E string. Viotti finds an even more arresting gesture, the violinist entering unaccompanied with an assertive version of the opening bass line; he also selects the E string, but soon transfers the idea down to the G string, a favourite timbre which Viotti did much to popularise. The two first movements follow a broadly similar course; both set off bravura display with contrasting melodic paragraphs, including a lyrical second subject and a more passionate minor-key episode. Viotti explores minor keys further in the development sections, with signs of the drama and turbulence to come in his later concertos; and it is perhaps significant of his serious approach to the concerto form, and his disdain of technical display for its own sake, that he does not even give the traditional opportunity for a cadenza.

The slow movement was usually either a graceful French romance, with its regular melody and easily-grasped structure, or a long-breathed expressive cantilena. Fiorillo’s Larghetto has something of the romance character about it, though the charming melody is more than a little reminiscent of Mozart. Viotti was by this date moving away from standard types, and his Andante, while retaining a simple design, is more concerned with the noble cantabile natural to the Tourte bow; the warm sonority of the movement stems directly from the sound of the horns.

Last movements were by this date almost universally rondos, featuring a recurring melody with some characteristic rhythm. Fiorillo finds a catchy tune in 2/4 time, which alternates with extrovertly showy episodes; one of these makes striking use of the horns in dialogue with the soloist, an unusual idea at a time when the wind instruments were often regarded as optional. Viotti prefers the triple time of the minuet—yet this is no stately court dance but rather a jaunty polonaise. Piquant national tunes were common enough as rondo themes, but this particular movement created a fashion for the polonaise finale; and, in a curious reversal of the norm, the melody itself became highly popular as a song. Again the episodes contain some brilliant passagework (one idea is a flashy combination of trill and dotted rhythm), but Fiorillo finds time once more for a minor-key contrast. There is one final surprise—the last time the rondo theme recurs it is heard in the orchestra, accompanied now by that distinctive figure in the solo violin part.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads