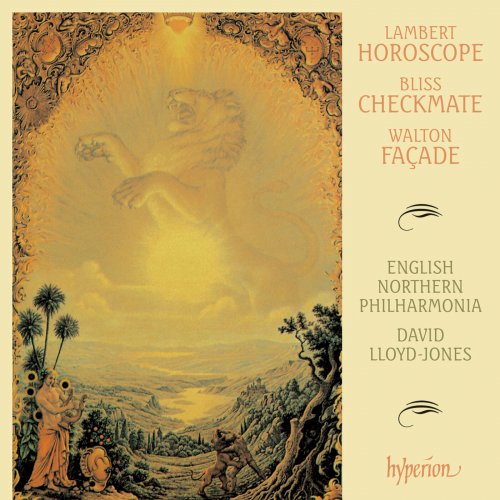

The Orchestra Of Opera North, David Lloyd-Jones - Lambert: Horoscope - Bliss: Checkmate - Walton: Façade (1990)

BAND/ARTIST: The Orchestra Of Opera North, David Lloyd-Jones

- Title: Lambert: Horoscope - Bliss: Checkmate - Walton: Façade

- Year Of Release: 1990

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:14:26

- Total Size: 288 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Horoscope, Ballet Suite: I. Dance for the Followers of Leo

02. Horoscope, Ballet Suite: II. Saraband for the Followers of Virgo

03. Horoscope, Ballet Suite: III. Valse for the Gemini

04. Horoscope, Ballet Suite: IV. Bacchanale

05. Horoscope, Ballet Suite: V. Invocation to the Moon and Finale

06. Façade Suite No. 2: I. Fanfare

07. Façade Suite No. 2: II. Scotch Rhapsody

08. Façade Suite No. 1: II. Valse

09. Façade Suite No. 1: IV. Tango-Pasodoble (Arr. Palmer)

10. Façade Suite No. 1: III. Swiss Jodelling Song

11. Façade Suite No. 2: III. Country Dance

12. Façade Suite No. 1: I. Polka

13. Façade Suite No. 2: IV. Noche española

14. Façade Suite No. 2: V. Popular Song

15. Façade Suite No. 2: VI. Old Sir Faulk

16. Façade Suite No. 1: V. Tarantella-Sevillana

17. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: I. Prologue. The Players

18. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: II. Dance of the Four Knights

19. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: III. Entry of the Black Queen

20. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: IV. The Red Knight's Mazurka

21. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: V. Ceremony of the Red Bishops

22. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: VI. Finale. Checkmate

Few past presidents of the Kensington Kittens’ and Neuter Cats’ Club (Incorporated) have had an entire record devoted to their achievements as composer and conductor; but the range of Constant Lambert’s accomplishment did not restrict itself to composing and conducting or, for that matter, to cat-fancying (he was also a connoisseur of bats and fish). Lambert: speaker, talker, essayist, wit, a penetrating and original thinker not only about music—his book Music Ho! is a classic—but also in the realms of art and literature, both of which he knew and understood from the inside out. This is rare, if not unique. Lambert was a cosmopolitan in an age where much was provincial and complacent; he was an individualist and tended to be disliked by the Establishment with its habitual mistrust of anyone who claims to be a jack of more than one trade—and proves himself a master of them all. The painter Michael Ayrton said there was a ‘richness’ about Lambert which he had never encountered in anyone else—‘he was enormous in the variety and curiosity of his knowledge’—and this ‘richness’ was invaluable in relation to the causes and the people, older, younger or the same age, whose cause he espoused.

This collection celebrates one of the most important of Lambert’s enthusiasms—ballet. From 1931 to 1947 he was conductor and musical director to the Vic-Wells Ballet, in which capacity, it is generally agreed, he raised the status of ballet in England to a level it otherwise might never have attained. Sir Frederick Ashton considered him the finest ballet conductor with whom he ever worked; even more important than his sense of rhythm was his inspiriting presence in the pit. Lambert’s all-round, in-depth culture was particularly valuable in the context of ballet, which partakes of many arts. When the young Robert Helpmann arrived from Australia in 1933, Lambert helped him by suggesting books he should read, pictures he should look at, and music he should listen to, and later discussed with him whatever he had managed to read, see and hear. Margot Fonteyn was also a protégé of Lambert in this respect. Among the many ballet scores first performed by Lambert were Vaughan Williams’s Job in its theatre version, Walton’s Quest and Façade, and Bliss’s Checkmate, Miracle in the Gorbals and Adam Zero—all major works.

Lambert composed four ballets of his own—Romeo and Juliet in 1924–6 (the first ballet commissioned by Diaghilev from an Englishman; Lambert was twenty), Pomona (1926), Horoscope (1937) and Tiresias (1950/51). Romeo and Juliet and Pomona are still in thrall to the Stravinsky of Petrushka and Pulcinella, while Tiresias, remembered by Tom Driberg as a score of ‘strange and wild beauty’, was unpublished and unperformed until recorded by Hyperion in 1998 (CDA67049). Horoscope is the most traditional, and for that reason no doubt the most popular of these ballets. The ‘tradition’ is that of Tchaikovsky and thence of the pre-war Diaghilev Russian Ballet. When Lambert says of Tchaikovsky that in a work like Swan Lake he’d managed to reconcile the physical and classical demands of the dance with the emotional and romantic demands of the story, he could easily be describing his own achievement in Horoscope; and if romantic or lyrical elements predominate we need look no further than the name of the dedicatee for the reason. Margot Fonteyn and Lambert had a close relationship for a number of years, and there is surely no harm in suggesting that in the last movement of Horoscope, ‘Invocation to the Moon and Finale’, the strength of their love is both attested and immortalised.

Lambert provided the following statement of the ‘theme’ of his ballet: ‘When people are born they have the sun in one sign of the Zodiac, the moon in another. This ballet takes for its theme a man who has the sun in Leo and the moon in Gemini, and a woman who also has the moon in Gemini but whose sun is in Virgo. The two opposed signs of Leo and Virgo, the one energetic and full-blooded, the other timid and sensitive, struggle to keep the man and the woman apart. It is by their mutual sign, Gemini, that they are brought together, and by the moon that they are finally united.’

Horoscope was first produced at Sadler’s Wells in January 1938. Ashton was the choreographer, Michael Somes danced the Man, Fonteyn the Woman; Lambert himself conducted. It was typical of Lambert’s involvement in all artistic aspects of his work that for the cover of the published scores (orchestral and piano) he arranged for a horoscope chart to be specially drawn by Edmund Dulac. The concert suite accounts for about two-thirds of the complete score (25 minutes out of 35).

The Walton–Lambert relationship was a close one, both personally and musically, and has yet to be examined in detail. It seems that though Lambert was the younger by three years or so, he was the natural mentor and guide, rather than the other way around. Certainly he was associated with Façade—Walton’s first major work—almost from its inception. In its original form it was an ‘entertainment’ for speaker(s) and instrumental ensemble; in Walton’s estimation Lambert was one of the best speakers the work ever attracted, and a famous early recording of selected numbers exists in which Lambert shares the speaking role with Edith Sitwell, the authoress of the poems. Lambert was the dedicatee of Façade and collaborated with Walton on ‘Four in the Morning’ (not in the suites). In fact in many ways Façade is Walton’s most Lambertian work, not least in its recreation or stylisation of popular idioms.

Lambert once wrote of the Sitwells’ (Edith and Sacheverell’s) poems that for all their ‘modernistic’ overtones they belonged in reality more to the classic tradition of English poetry, ‘more particularly that of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when beauty was not yet divorced from wit, and when it was realised that artifice and sincerity were not necessarily antagonistic’. He could just as easily have been describing the music of Façade. In Music Ho! he praises the latter as one of the few successful examples since Chabrier of ‘sophisticated music with a popular allure’, the ‘concentrated brevity’ of its contrasting numbers, ‘satiric genre pieces, over in a flash but unerringly pinning down some aspect of popular music, whether foxtrot, tango or tarantella’ being in his view one of the strongest features of Façade. Another was the tunes—‘one good tune after another, the waltz is an excellent waltz, the tarantella an excellent tarantella. Theirs is not the obvious humour of a Beerbohm parody. They are not only like the originals but ridiculously like’. Lambert also considered that, for Walton, writing in a popular idiom had the salutary effect of clarifying his melodic line, but for which the poetic achievement of the Viola Concerto or the slow movement of the Sinfonia Concertante would not have been as great.

In 1926 Walton took five of the more self-contained numbers of Façade, omitted the speaking voice, and transcribed the instrumentation for medium orchestra. Lambert dcscribed this suite as a ‘very enjoyable work’ while admitting that it represented but one side of Façade, the brilliant, satirical side. Lambert looked in vain for the pastoral charm of ‘Daphne’, or the sinister atmosphere of ‘Four in the Morning’—forgetting, presumably, that these could not have stood upon their own without the speaker and would have needed to be completely re-composed. Clearly Walton wanted to keep as closely as possible to the form and rhythm of the original settings. Lambert noted ‘the only piece in which he has departed from the original form of the poem is the Tarantella-Sevillana, perhaps the most successful number in the suite, where the material has been considerably expanded into a brilliant burlesque of the ‘Mediterranean’ style’.

It was this first suite which attracted the attention of three major choreographers—Gunter Hess in 1929, Frederick Ashton in 1931, and John Cranko in 1961. The second production, of course, was the one with which Lambert was associated. He conducted the first performance of this ballet when the Camargo Society gave it in London in April 1931, and almost certainly scored the extra Façade numbers incorporated both on this occasion and in 1935 when the Vic-Wells Ballet first danced the work. Only after the Second Suite for orchestra had been published in 1938 could the composer’s own orchestration be used for the entire ballet...

01. Horoscope, Ballet Suite: I. Dance for the Followers of Leo

02. Horoscope, Ballet Suite: II. Saraband for the Followers of Virgo

03. Horoscope, Ballet Suite: III. Valse for the Gemini

04. Horoscope, Ballet Suite: IV. Bacchanale

05. Horoscope, Ballet Suite: V. Invocation to the Moon and Finale

06. Façade Suite No. 2: I. Fanfare

07. Façade Suite No. 2: II. Scotch Rhapsody

08. Façade Suite No. 1: II. Valse

09. Façade Suite No. 1: IV. Tango-Pasodoble (Arr. Palmer)

10. Façade Suite No. 1: III. Swiss Jodelling Song

11. Façade Suite No. 2: III. Country Dance

12. Façade Suite No. 1: I. Polka

13. Façade Suite No. 2: IV. Noche española

14. Façade Suite No. 2: V. Popular Song

15. Façade Suite No. 2: VI. Old Sir Faulk

16. Façade Suite No. 1: V. Tarantella-Sevillana

17. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: I. Prologue. The Players

18. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: II. Dance of the Four Knights

19. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: III. Entry of the Black Queen

20. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: IV. The Red Knight's Mazurka

21. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: V. Ceremony of the Red Bishops

22. Checkmate, Ballet Suite: VI. Finale. Checkmate

Few past presidents of the Kensington Kittens’ and Neuter Cats’ Club (Incorporated) have had an entire record devoted to their achievements as composer and conductor; but the range of Constant Lambert’s accomplishment did not restrict itself to composing and conducting or, for that matter, to cat-fancying (he was also a connoisseur of bats and fish). Lambert: speaker, talker, essayist, wit, a penetrating and original thinker not only about music—his book Music Ho! is a classic—but also in the realms of art and literature, both of which he knew and understood from the inside out. This is rare, if not unique. Lambert was a cosmopolitan in an age where much was provincial and complacent; he was an individualist and tended to be disliked by the Establishment with its habitual mistrust of anyone who claims to be a jack of more than one trade—and proves himself a master of them all. The painter Michael Ayrton said there was a ‘richness’ about Lambert which he had never encountered in anyone else—‘he was enormous in the variety and curiosity of his knowledge’—and this ‘richness’ was invaluable in relation to the causes and the people, older, younger or the same age, whose cause he espoused.

This collection celebrates one of the most important of Lambert’s enthusiasms—ballet. From 1931 to 1947 he was conductor and musical director to the Vic-Wells Ballet, in which capacity, it is generally agreed, he raised the status of ballet in England to a level it otherwise might never have attained. Sir Frederick Ashton considered him the finest ballet conductor with whom he ever worked; even more important than his sense of rhythm was his inspiriting presence in the pit. Lambert’s all-round, in-depth culture was particularly valuable in the context of ballet, which partakes of many arts. When the young Robert Helpmann arrived from Australia in 1933, Lambert helped him by suggesting books he should read, pictures he should look at, and music he should listen to, and later discussed with him whatever he had managed to read, see and hear. Margot Fonteyn was also a protégé of Lambert in this respect. Among the many ballet scores first performed by Lambert were Vaughan Williams’s Job in its theatre version, Walton’s Quest and Façade, and Bliss’s Checkmate, Miracle in the Gorbals and Adam Zero—all major works.

Lambert composed four ballets of his own—Romeo and Juliet in 1924–6 (the first ballet commissioned by Diaghilev from an Englishman; Lambert was twenty), Pomona (1926), Horoscope (1937) and Tiresias (1950/51). Romeo and Juliet and Pomona are still in thrall to the Stravinsky of Petrushka and Pulcinella, while Tiresias, remembered by Tom Driberg as a score of ‘strange and wild beauty’, was unpublished and unperformed until recorded by Hyperion in 1998 (CDA67049). Horoscope is the most traditional, and for that reason no doubt the most popular of these ballets. The ‘tradition’ is that of Tchaikovsky and thence of the pre-war Diaghilev Russian Ballet. When Lambert says of Tchaikovsky that in a work like Swan Lake he’d managed to reconcile the physical and classical demands of the dance with the emotional and romantic demands of the story, he could easily be describing his own achievement in Horoscope; and if romantic or lyrical elements predominate we need look no further than the name of the dedicatee for the reason. Margot Fonteyn and Lambert had a close relationship for a number of years, and there is surely no harm in suggesting that in the last movement of Horoscope, ‘Invocation to the Moon and Finale’, the strength of their love is both attested and immortalised.

Lambert provided the following statement of the ‘theme’ of his ballet: ‘When people are born they have the sun in one sign of the Zodiac, the moon in another. This ballet takes for its theme a man who has the sun in Leo and the moon in Gemini, and a woman who also has the moon in Gemini but whose sun is in Virgo. The two opposed signs of Leo and Virgo, the one energetic and full-blooded, the other timid and sensitive, struggle to keep the man and the woman apart. It is by their mutual sign, Gemini, that they are brought together, and by the moon that they are finally united.’

Horoscope was first produced at Sadler’s Wells in January 1938. Ashton was the choreographer, Michael Somes danced the Man, Fonteyn the Woman; Lambert himself conducted. It was typical of Lambert’s involvement in all artistic aspects of his work that for the cover of the published scores (orchestral and piano) he arranged for a horoscope chart to be specially drawn by Edmund Dulac. The concert suite accounts for about two-thirds of the complete score (25 minutes out of 35).

The Walton–Lambert relationship was a close one, both personally and musically, and has yet to be examined in detail. It seems that though Lambert was the younger by three years or so, he was the natural mentor and guide, rather than the other way around. Certainly he was associated with Façade—Walton’s first major work—almost from its inception. In its original form it was an ‘entertainment’ for speaker(s) and instrumental ensemble; in Walton’s estimation Lambert was one of the best speakers the work ever attracted, and a famous early recording of selected numbers exists in which Lambert shares the speaking role with Edith Sitwell, the authoress of the poems. Lambert was the dedicatee of Façade and collaborated with Walton on ‘Four in the Morning’ (not in the suites). In fact in many ways Façade is Walton’s most Lambertian work, not least in its recreation or stylisation of popular idioms.

Lambert once wrote of the Sitwells’ (Edith and Sacheverell’s) poems that for all their ‘modernistic’ overtones they belonged in reality more to the classic tradition of English poetry, ‘more particularly that of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when beauty was not yet divorced from wit, and when it was realised that artifice and sincerity were not necessarily antagonistic’. He could just as easily have been describing the music of Façade. In Music Ho! he praises the latter as one of the few successful examples since Chabrier of ‘sophisticated music with a popular allure’, the ‘concentrated brevity’ of its contrasting numbers, ‘satiric genre pieces, over in a flash but unerringly pinning down some aspect of popular music, whether foxtrot, tango or tarantella’ being in his view one of the strongest features of Façade. Another was the tunes—‘one good tune after another, the waltz is an excellent waltz, the tarantella an excellent tarantella. Theirs is not the obvious humour of a Beerbohm parody. They are not only like the originals but ridiculously like’. Lambert also considered that, for Walton, writing in a popular idiom had the salutary effect of clarifying his melodic line, but for which the poetic achievement of the Viola Concerto or the slow movement of the Sinfonia Concertante would not have been as great.

In 1926 Walton took five of the more self-contained numbers of Façade, omitted the speaking voice, and transcribed the instrumentation for medium orchestra. Lambert dcscribed this suite as a ‘very enjoyable work’ while admitting that it represented but one side of Façade, the brilliant, satirical side. Lambert looked in vain for the pastoral charm of ‘Daphne’, or the sinister atmosphere of ‘Four in the Morning’—forgetting, presumably, that these could not have stood upon their own without the speaker and would have needed to be completely re-composed. Clearly Walton wanted to keep as closely as possible to the form and rhythm of the original settings. Lambert noted ‘the only piece in which he has departed from the original form of the poem is the Tarantella-Sevillana, perhaps the most successful number in the suite, where the material has been considerably expanded into a brilliant burlesque of the ‘Mediterranean’ style’.

It was this first suite which attracted the attention of three major choreographers—Gunter Hess in 1929, Frederick Ashton in 1931, and John Cranko in 1961. The second production, of course, was the one with which Lambert was associated. He conducted the first performance of this ballet when the Camargo Society gave it in London in April 1931, and almost certainly scored the extra Façade numbers incorporated both on this occasion and in 1935 when the Vic-Wells Ballet first danced the work. Only after the Second Suite for orchestra had been published in 1938 could the composer’s own orchestration be used for the entire ballet...

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads