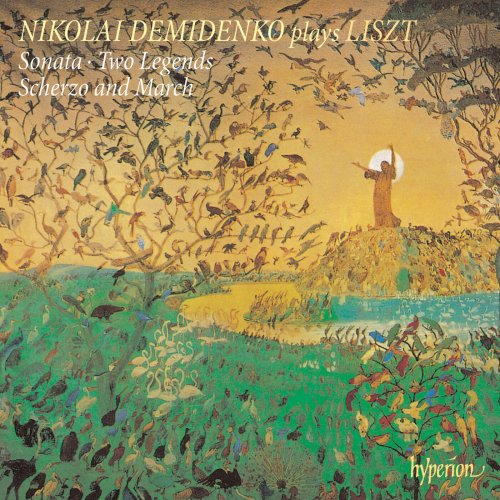

Nikolaï Demidenko - Liszt: Sonata in B Minor; 2 Legends; Scherzo & March (1992)

BAND/ARTIST: Nikolaï Demidenko

- Title: Liszt: Sonata in B Minor; 2 Legends; Scherzo & March

- Year Of Release: 1992

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:07:03

- Total Size: 205 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: Ia. Lento assai

02. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: Ib. Allegro energico

03. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IIa. Grandioso

04. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IIb. Cantando espressivo

05. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IIc. Pesante - Recitativo

06. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IIIa. Andante sostenuto

07. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IIIb. Quasi adagio

08. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVa. Allegro energico

09. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVa. Allegro energico (Cont.)

10. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVb. Più mosso

11. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVc. Cantando espressivo

12. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVd. Stretta quasi presto – IVe. Presto

13. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVe. (Continued) Prestissimo

14. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: Va. Andante sostenuto

15. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: Vb. Allegro moderato

16. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: Vc. Lento assai

17. Légendes, S. 175: Ia. St François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux. Allegretto

18. Légendes, S. 175: Ib. St François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux. Recitativo

19. Légendes, S. 175: Ic. St François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux. Solennemente

20. Légendes, S. 175: Id. St François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux. Dolcissimo

21. Légendes, S. 175: Ie. St François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux. Dolce

22. Légendes, S. 175: IIa. St François de Paule marchant sur les flots. Andante maestoso

23. Légendes, S. 175: IIb. St François de Paule marchant sur les flots. Allegro maestoso ed animato

24. Légendes, S. 175: IIc. St François de Paule marchant sur les flots. Lento

25. Scherzo und Marsch, S. 177: I. Allegro vivace, spiritoso

26. Scherzo und Marsch, S. 177: II. Allegro moderato, marziale

27. Scherzo und Marsch, S. 177: III. Allegro vivace, spiritoso

28. Scherzo und Marsch, S. 177: IV. Stretta

29. Scherzo und Marsch, S. 177: V. Molto più animato, quasi presto

Liszt’s most consummate work for piano – a unique study in thematic transformation, an essay of complex structural organization, of wondrous tonal insights and enigmatic harmonic manifestations, of molten no less than fragile keyboard layout – the Piano Sonata in B minor (1851–1853) was first performed in public in Berlin by Hans von Bülow (Liszt’s pupil and son-in-law) at a concert given on 22 January 1857 to inaugurate the first grand piano to be made by Carl Bechstein. ‘An unexpected, almost unanimous success … completely [dumbfounding] the cretinous scoundrels’, was Bülow’s verdict to the composer. Liszt dedicated it to Schumann.

Architecturally, after the model of Schubert’s motto-cyclic ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy, a favourite work of Liszt’s, the whole (like the Grosses Konzertsolo of around 1849) is cast in the form of a single polymorphous movement divided into sections. The particular function and chemistry of these sections has been analytically interpreted in many ways; the present writer’s ‘Wanderer’-derived blueprint places emphasis on a four-movement-within-one ground plan, framed by a ‘Prologue’ and ‘Epilogue’:

Prologue: ‘Lento assai’

Exposition (‘first movement’): ‘Allegro energico’ to ‘Pesante / Recitativo’

Development I (‘slow movement’): ‘Andante sostenuto’ and ‘Quasi Adagio’

Scherzo-fugato / Development II (‘third movement’): ‘Allegro energico’

Recapitulation (‘fourth movement’): ‘Allegro energico’ to ‘Prestissimo’

Epilogue: ‘Andante sostenuto’ to the end

Tonally, Liszt explores tensions at once Classical, Romantic and futuristic. He is at his most Classical in the ‘exposition’ and ‘recapitulation’, with first and second subject groups initially in the tonic (B minor) and relative major (D), and latterly in tonic minor and major. Likewise, his ‘Andante sostenuto — Quasi Adagio’ (on a theme sketched in a notebook of 1849) is broadly in F sharp, the dominant. However, how he travels between and contextualizes these keys shows him in essentially Romantic light: for instance, in the ‘exposition’, the ‘flat’ orientation of the transition between the B minor agitato of the ‘Allegro energico’ (a combination of the second and third themes of the work) and both the D major ‘Grandioso’ idea (the ‘ardent virtuoso, head thrown back’ tune of Walter Beckett’s biography, 1956) and the ‘Cantando espressivo’; the ‘flat’ A major and ‘sharp’ G minor operatic interpolations of the ‘slow movement’; the B flat minor key of the ‘Scherzo-fugato’ (a section whose duple time signature and short staccato seem to remember the Beethoven of Op 31 No 3); and the heroic, volcanic importance of E flat major.

Programmatically, Liszt provides us with no clues as to the character or meaning of his themes. As Searle confirms, ‘the B minor Sonata … does not attempt to tell a story’. However, from the evidence of his students (who, according to his grand-pupil Claudio Arrau, took the fact for granted), the example of Alkan’s earlier Quasi-Faust published in Paris in 1847 (with which the B minor shares – to the point of even occasional plagiarism – strong melodic, structural and conceptual ties, including a fugue), and the thematic/descriptive proof of his own later Faust Symphony, we may assume them to have general associations with the Faust, Mephistopheles and Gretchen story of Goethe’s drama, all traceable in one guise or another. In Arrau’s view, ‘I think of the Sonata as a great Faustian tone-poem, with Gretchen, Faust and Mephistopheles all playing out their archetypal roles of transcendence, redemption and negation’. Brendel, while admitting it does not need a programme, also likens its macrocosm to a ‘Faust-Mephisto-Gretchen constellation’.

In her book on Liszt (1974), Eleanor Perényi calls the B minor Sonata ‘a kind of cosmic self-portrait’. It ‘recasts the familiar sonata form’, she says, ‘into a single unit in which the motifs are twisted, unwound, rewoven like a serpent’s coils. It moves like some extraordinary, iridescent object through space, now grandiose, now threatening, now heavenly, until it explodes into one of the great climaxes in piano literature, dying away to an exquisite epilogue. In Liszt’s hands, it must have been miraculous.’

Brahms, like Clara Schumann, failed to appreciate it. Hanslick ravaged it (‘this musical monstrosity’). Sitwell could find no enthusiasm. But Wagner celebrated, joyously: a work ‘beautiful beyond all conception; great, lovely, deep and noble, sublime even as thyself. I feel most profoundly moved …’ (London, 5 April 1855).

Published in 1866, with a dedication to his daughter Cosima, Liszt’s Two Legends were completed by 1863 at latest. A poem of the most precious perfume – filigreed, delicate and solemn – the first (in A major, with a sermon in D flat) was inspired by a well-known passage from the Little Flowers of Assisi:

He lifted up his eyes and saw the trees which stood by the wayside filled with a countless multitude of birds, at which he marvelled and said to his companions: ‘Wait a little for me in the road, and I will go and preach to my little brothers the birds.’ And he went into the field, and began to preach to the birds that were on the ground, and forthwith those which were in the trees came around him and not one moved during the whole sermon, nor would they fly away until the Saint had given them his blessing.

The second (in E major) is about Francis of Paola (Liszt’s patron saint), the Calabrian who is said to have walked across the waters of Messina, his cloak spread before him like a sail. In it the sea veritably roars and thunders, Francis’s theme rising out of the deep, weathering the storms and whirlpools of Scylla and Charybdis finally to bid us farewell in a miraculous blaze of celestial light and glory.

New evidence suggests that both pieces were written originally for orchestra, in which form they were premiered in Berlin in October 1982.

Described in the autograph as a ‘Concertstuck [sic] für das Pianoforte’, the Scherzo and March, dedicated to Theodor Kullak, court pianist to the King of Prussia, appeared in 1851. A hellish ‘night ride’ of extraordinary dimension and sustained originality, inflamed by a pianism of colossal, high speed, rhythmic athleticism (a relentless onslaught of brittle digital dexterity, or massive block and quasi trillo chords, of muscular double-octave thunder, all unleashed within a dynamic spectrum of pp to fff, and all directed towards the creation of a texture frequently bizarre in the Alkanesque spacing of its extremes), it belongs among the least familiar of the great Liszt epics. Physically exhausting, emotionally draining, re-creatively challenging, the enormity and terror of its pianistic universe are not for the faint-hearted: to survive its galvanic journey is to knowingly triumph over some of the most awesome difficulties in the entire history of Romantic piano technique. Like the 1838 version of the Transcendental Studies, what it documents, memorably, is a wholly new kind of energizing virtuosity.

Architecturally, Louis Kentner has observed (1970), the Scherzo (in D minor) – in the tradition of Beethoven’s Ninth, a work Liszt knew intimately – is in sonata form, prefaced by an introduction, ‘Allegro vivace, spiritoso’. More a seed-bed of atmospheric invocation than germinal melody, this introduction, whispered and mocking, is concerned broadly with a staccato left-hand figure of Second Concerto-like identity. Precisely delineated, on-going in elaboration, the main thrust of the exposition revolves around two principal subject groups. The first of these, macabre and underlined by an unrelieved mood of nocturnal hellishness, polymetrically juxtaposes material in 2/4 and 6/8; the second, arrestingly unisonal, is in the dominant minor. Preceded by an exegesis combined of elements drawn from the second subject and introduction, the development section, a scena of cinematically diabolonian encounter, dwells amid fantasies of burgeoning spectral shape and sound. Opening with a flashback to the introduction (by now an important signpost) and punctuated by ‘presto strepitoso’ episodes of malignant Mephistophelian laughter, its substance is established by fragments of the first subject (in B minor) offset by an angular fugal interpolation anticipative in many ways of things to come in the sonata and the Faust Symphony. For musico-dramatic reasons, the recapitulation, heralded by a prestissimo re-transition, is curtailed.

The central March, ‘Allegretto moderato’, is in B flat, but it’s an adulterated B flat, coloured by an insistent minorially flattened sixth that intonationally is to the immediate context what B flat tonally is to the whole. Liszt gives us a magnificently idiomatic and personal vision, a grand march of the spirit. True, his models are discernible. On the one hand, Beethoven: the key and style of the ‘Alla marcia’ variation from the Ninth’s finale. On the other, Weber: the crescendo by repetition, the climax, the sudden decay of the march from the Konzertstück (an old repertoire stomping ground). But what he does with his material is unique to himself: for example, how he excites sudden shifts of key – from B flat mp to B flat ff by way of G flat, D flat, E, D and C sharp, plus some inevitable augmented triad referencing – to create tension and impulsion. And how he re-harmonizes the March theme on its final fff marcatissimo appearance to set the whole instrument suddenly roaring in a resonance of clangorous, fearful tumult.

The final third of the work is occupied with a partial recapitulation of the Scherzo (a reprise of the first subject in D minor) and a closing coda-development in the Beethoven manner, ‘Stretta’, based on fragments from the March in conflict with the second subject of the Scherzo twisted into the tonic major (D) but with the flattened-sixth (now B flat) and flattened-second (now E flat) inflexion of its original minor key presentation retained. ‘It is’, Kentner says, ‘as if religion [the March (God)] were doing battle with the Devil [the Scherzo].’ This major/minor confusion is maintained right to the end. Even when D major seems to be unequivocally proclaimed, a B flat irritant makes sure that it isn’t quite.

01. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: Ia. Lento assai

02. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: Ib. Allegro energico

03. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IIa. Grandioso

04. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IIb. Cantando espressivo

05. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IIc. Pesante - Recitativo

06. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IIIa. Andante sostenuto

07. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IIIb. Quasi adagio

08. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVa. Allegro energico

09. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVa. Allegro energico (Cont.)

10. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVb. Più mosso

11. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVc. Cantando espressivo

12. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVd. Stretta quasi presto – IVe. Presto

13. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: IVe. (Continued) Prestissimo

14. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: Va. Andante sostenuto

15. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: Vb. Allegro moderato

16. Piano Sonata in B Minor, S. 178: Vc. Lento assai

17. Légendes, S. 175: Ia. St François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux. Allegretto

18. Légendes, S. 175: Ib. St François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux. Recitativo

19. Légendes, S. 175: Ic. St François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux. Solennemente

20. Légendes, S. 175: Id. St François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux. Dolcissimo

21. Légendes, S. 175: Ie. St François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux. Dolce

22. Légendes, S. 175: IIa. St François de Paule marchant sur les flots. Andante maestoso

23. Légendes, S. 175: IIb. St François de Paule marchant sur les flots. Allegro maestoso ed animato

24. Légendes, S. 175: IIc. St François de Paule marchant sur les flots. Lento

25. Scherzo und Marsch, S. 177: I. Allegro vivace, spiritoso

26. Scherzo und Marsch, S. 177: II. Allegro moderato, marziale

27. Scherzo und Marsch, S. 177: III. Allegro vivace, spiritoso

28. Scherzo und Marsch, S. 177: IV. Stretta

29. Scherzo und Marsch, S. 177: V. Molto più animato, quasi presto

Liszt’s most consummate work for piano – a unique study in thematic transformation, an essay of complex structural organization, of wondrous tonal insights and enigmatic harmonic manifestations, of molten no less than fragile keyboard layout – the Piano Sonata in B minor (1851–1853) was first performed in public in Berlin by Hans von Bülow (Liszt’s pupil and son-in-law) at a concert given on 22 January 1857 to inaugurate the first grand piano to be made by Carl Bechstein. ‘An unexpected, almost unanimous success … completely [dumbfounding] the cretinous scoundrels’, was Bülow’s verdict to the composer. Liszt dedicated it to Schumann.

Architecturally, after the model of Schubert’s motto-cyclic ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy, a favourite work of Liszt’s, the whole (like the Grosses Konzertsolo of around 1849) is cast in the form of a single polymorphous movement divided into sections. The particular function and chemistry of these sections has been analytically interpreted in many ways; the present writer’s ‘Wanderer’-derived blueprint places emphasis on a four-movement-within-one ground plan, framed by a ‘Prologue’ and ‘Epilogue’:

Prologue: ‘Lento assai’

Exposition (‘first movement’): ‘Allegro energico’ to ‘Pesante / Recitativo’

Development I (‘slow movement’): ‘Andante sostenuto’ and ‘Quasi Adagio’

Scherzo-fugato / Development II (‘third movement’): ‘Allegro energico’

Recapitulation (‘fourth movement’): ‘Allegro energico’ to ‘Prestissimo’

Epilogue: ‘Andante sostenuto’ to the end

Tonally, Liszt explores tensions at once Classical, Romantic and futuristic. He is at his most Classical in the ‘exposition’ and ‘recapitulation’, with first and second subject groups initially in the tonic (B minor) and relative major (D), and latterly in tonic minor and major. Likewise, his ‘Andante sostenuto — Quasi Adagio’ (on a theme sketched in a notebook of 1849) is broadly in F sharp, the dominant. However, how he travels between and contextualizes these keys shows him in essentially Romantic light: for instance, in the ‘exposition’, the ‘flat’ orientation of the transition between the B minor agitato of the ‘Allegro energico’ (a combination of the second and third themes of the work) and both the D major ‘Grandioso’ idea (the ‘ardent virtuoso, head thrown back’ tune of Walter Beckett’s biography, 1956) and the ‘Cantando espressivo’; the ‘flat’ A major and ‘sharp’ G minor operatic interpolations of the ‘slow movement’; the B flat minor key of the ‘Scherzo-fugato’ (a section whose duple time signature and short staccato seem to remember the Beethoven of Op 31 No 3); and the heroic, volcanic importance of E flat major.

Programmatically, Liszt provides us with no clues as to the character or meaning of his themes. As Searle confirms, ‘the B minor Sonata … does not attempt to tell a story’. However, from the evidence of his students (who, according to his grand-pupil Claudio Arrau, took the fact for granted), the example of Alkan’s earlier Quasi-Faust published in Paris in 1847 (with which the B minor shares – to the point of even occasional plagiarism – strong melodic, structural and conceptual ties, including a fugue), and the thematic/descriptive proof of his own later Faust Symphony, we may assume them to have general associations with the Faust, Mephistopheles and Gretchen story of Goethe’s drama, all traceable in one guise or another. In Arrau’s view, ‘I think of the Sonata as a great Faustian tone-poem, with Gretchen, Faust and Mephistopheles all playing out their archetypal roles of transcendence, redemption and negation’. Brendel, while admitting it does not need a programme, also likens its macrocosm to a ‘Faust-Mephisto-Gretchen constellation’.

In her book on Liszt (1974), Eleanor Perényi calls the B minor Sonata ‘a kind of cosmic self-portrait’. It ‘recasts the familiar sonata form’, she says, ‘into a single unit in which the motifs are twisted, unwound, rewoven like a serpent’s coils. It moves like some extraordinary, iridescent object through space, now grandiose, now threatening, now heavenly, until it explodes into one of the great climaxes in piano literature, dying away to an exquisite epilogue. In Liszt’s hands, it must have been miraculous.’

Brahms, like Clara Schumann, failed to appreciate it. Hanslick ravaged it (‘this musical monstrosity’). Sitwell could find no enthusiasm. But Wagner celebrated, joyously: a work ‘beautiful beyond all conception; great, lovely, deep and noble, sublime even as thyself. I feel most profoundly moved …’ (London, 5 April 1855).

Published in 1866, with a dedication to his daughter Cosima, Liszt’s Two Legends were completed by 1863 at latest. A poem of the most precious perfume – filigreed, delicate and solemn – the first (in A major, with a sermon in D flat) was inspired by a well-known passage from the Little Flowers of Assisi:

He lifted up his eyes and saw the trees which stood by the wayside filled with a countless multitude of birds, at which he marvelled and said to his companions: ‘Wait a little for me in the road, and I will go and preach to my little brothers the birds.’ And he went into the field, and began to preach to the birds that were on the ground, and forthwith those which were in the trees came around him and not one moved during the whole sermon, nor would they fly away until the Saint had given them his blessing.

The second (in E major) is about Francis of Paola (Liszt’s patron saint), the Calabrian who is said to have walked across the waters of Messina, his cloak spread before him like a sail. In it the sea veritably roars and thunders, Francis’s theme rising out of the deep, weathering the storms and whirlpools of Scylla and Charybdis finally to bid us farewell in a miraculous blaze of celestial light and glory.

New evidence suggests that both pieces were written originally for orchestra, in which form they were premiered in Berlin in October 1982.

Described in the autograph as a ‘Concertstuck [sic] für das Pianoforte’, the Scherzo and March, dedicated to Theodor Kullak, court pianist to the King of Prussia, appeared in 1851. A hellish ‘night ride’ of extraordinary dimension and sustained originality, inflamed by a pianism of colossal, high speed, rhythmic athleticism (a relentless onslaught of brittle digital dexterity, or massive block and quasi trillo chords, of muscular double-octave thunder, all unleashed within a dynamic spectrum of pp to fff, and all directed towards the creation of a texture frequently bizarre in the Alkanesque spacing of its extremes), it belongs among the least familiar of the great Liszt epics. Physically exhausting, emotionally draining, re-creatively challenging, the enormity and terror of its pianistic universe are not for the faint-hearted: to survive its galvanic journey is to knowingly triumph over some of the most awesome difficulties in the entire history of Romantic piano technique. Like the 1838 version of the Transcendental Studies, what it documents, memorably, is a wholly new kind of energizing virtuosity.

Architecturally, Louis Kentner has observed (1970), the Scherzo (in D minor) – in the tradition of Beethoven’s Ninth, a work Liszt knew intimately – is in sonata form, prefaced by an introduction, ‘Allegro vivace, spiritoso’. More a seed-bed of atmospheric invocation than germinal melody, this introduction, whispered and mocking, is concerned broadly with a staccato left-hand figure of Second Concerto-like identity. Precisely delineated, on-going in elaboration, the main thrust of the exposition revolves around two principal subject groups. The first of these, macabre and underlined by an unrelieved mood of nocturnal hellishness, polymetrically juxtaposes material in 2/4 and 6/8; the second, arrestingly unisonal, is in the dominant minor. Preceded by an exegesis combined of elements drawn from the second subject and introduction, the development section, a scena of cinematically diabolonian encounter, dwells amid fantasies of burgeoning spectral shape and sound. Opening with a flashback to the introduction (by now an important signpost) and punctuated by ‘presto strepitoso’ episodes of malignant Mephistophelian laughter, its substance is established by fragments of the first subject (in B minor) offset by an angular fugal interpolation anticipative in many ways of things to come in the sonata and the Faust Symphony. For musico-dramatic reasons, the recapitulation, heralded by a prestissimo re-transition, is curtailed.

The central March, ‘Allegretto moderato’, is in B flat, but it’s an adulterated B flat, coloured by an insistent minorially flattened sixth that intonationally is to the immediate context what B flat tonally is to the whole. Liszt gives us a magnificently idiomatic and personal vision, a grand march of the spirit. True, his models are discernible. On the one hand, Beethoven: the key and style of the ‘Alla marcia’ variation from the Ninth’s finale. On the other, Weber: the crescendo by repetition, the climax, the sudden decay of the march from the Konzertstück (an old repertoire stomping ground). But what he does with his material is unique to himself: for example, how he excites sudden shifts of key – from B flat mp to B flat ff by way of G flat, D flat, E, D and C sharp, plus some inevitable augmented triad referencing – to create tension and impulsion. And how he re-harmonizes the March theme on its final fff marcatissimo appearance to set the whole instrument suddenly roaring in a resonance of clangorous, fearful tumult.

The final third of the work is occupied with a partial recapitulation of the Scherzo (a reprise of the first subject in D minor) and a closing coda-development in the Beethoven manner, ‘Stretta’, based on fragments from the March in conflict with the second subject of the Scherzo twisted into the tonic major (D) but with the flattened-sixth (now B flat) and flattened-second (now E flat) inflexion of its original minor key presentation retained. ‘It is’, Kentner says, ‘as if religion [the March (God)] were doing battle with the Devil [the Scherzo].’ This major/minor confusion is maintained right to the end. Even when D major seems to be unequivocally proclaimed, a B flat irritant makes sure that it isn’t quite.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads