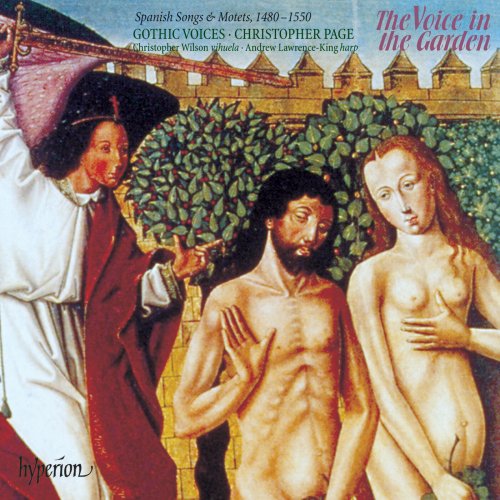

Gothic Voices, Christopher Page - The Voice in the Garden: Spanish Songs & Motets, 1480-1550 (1993)

BAND/ARTIST: Gothic Voices, Christopher Page

- Title: The Voice in the Garden: Spanish Songs & Motets, 1480-1550

- Year Of Release: 1993

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 00:52:07

- Total Size: 208 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Mi libertad en sosiego

02. A la villa voy

03. Passe el agoa

04. Harto de tanta porfía

05. Fantasia Tercer tono

06. Por las sierras de Madrid

07. Ne reminiscaris, Domine

08. Dindirín, dindirín

09. Fantasia Segundo tono

10. Ave, virgo, gratia plena

11. Yo creo que n'os dió Dios

12. Fantasia 10

13. Precor te, Domine Jesu Christe

14. Tiento

15. Los sospiros No sosiegan

16. Paseávase el rey moro

17. Mi querer tanto vos quiere

18. Fantasia 18

19. Dentro en el vergel moriré

20. Entra Mayo y sale Abril

21. Fantasia 12

22. La bella malmaridada

23. Sancta Maria

‘History is the essence of innumerable biographies’, wrote Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), while Schlegel (1772–1829) commented that ‘A historian is a prophet in reverse’. These are precisely the problems that beset any study of early music: much of the surviving music is anonymous, and because so little of it, comparatively speaking, has survived, the retrospective prophecies of music historians are based on fragmentary evidence. Consider the history of Spanish polyphonic song: no songbooks of Castilian-texted songs survive from before the end of the fifteenth century. Between them, these songbooks contain some five hundred songs; that is a fair number, one might think, but it is only the tip of the cancionero iceberg, to judge by the quantity of lyric verse dating from the period 1450–1530, the time when the first flowering of Spanish polyphonic song apparently occurred. However, these songs represent a notated repertory: there is plenty of extra-musical evidence to suggest that an improvised (or at least unwritten) song tradition existed much earlier in Spain. Any prophecies in reverse about developments in song forms, styles or themes must therefore take account of a practice we cannot hope to explore or describe.

The songbooks preserved in Madrid (the ‘Palace Songbook’), in Seville, Barcelona, Segovia and Elvas, present many unresolved mysteries, not least because they contain so many anonymous pieces. The attributions which are to be found in the songbooks explain why these manuscripts have long been associated with the households of the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. Most of the composers named there were singers who served at various times in either the Aragonese or the Castilian court chapels. Of these royal singers, Francisco de Peñalosa (c1470–1528) was undoubtedly the leading light, yet we know surprisingly little about his life. The bare facts are that he entered the Aragonese chapel in 1498, served there until the death of King Ferdinand in 1516 and subsequently joined the papal chapel in Rome before returning to Seville, where he held a canonry. There he passed his final years. It is immediately apparent from his cantus firmus Mass settings, which closely follow Franco-Netherlandish models in their subtle deployment of borrowed melodies, both sacred and secular, that he was a composer of considerable technical skill. Indeed, this is a technique that he extends, with a flourish of ingenuity, to one of his songs in the Palace Songbook. In Por las sierras de Madrid he combines four popular melodies, all well-known refrains, adding a fifth borrowing in the bass, a Latin gloss taken from the Acts of the Apostles, which punningly alludes to the polytextuality of the upper voices: ‘They tell out in many languages the mighty deeds of God’.

In his motets, Peñalosa is less concerned with artifice than with an expressive projection of the texts. These are generally devotional in nature, with Marian (Sancta Maria) and penitential (Ne reminiscaris) themes predominant. Peñalosa’s approach to text-setting in his motets—surely influenced by his studies with the Sicilian humanist Lucas Marineus who taught Latin to the members of the Aragonese chapel—is largely syllabic, with due attention to the correct accentuation of the words and melismas largely restricted to the penultimate syllable of a phrase. Often entirely free of borrowed material, these motets use the phrase structure of the text as the basis for the musical framework. Peñalosa exploited this expressive freedom to the full, notably in the four-voice Precor te, Domine, a meditation on the sufferings of Christ on the Cross. Here the declamatory, homophonic sections intensify the affective character of certain passages in the text, the effect being rendered still more dramatic by the use of rests to offset these words.

Humanist tendencies are also apparent in the works of the poet, playwright and composer Juan del Encina (1468–1529/30). A little more is known of his life—his training at Salamanca, his period of service at the court of the Duke of Alba in the 1490s, and his subsequent sojourn in Rome—yet he appears never to have served in the royal chapels of Ferdinand and Isabella, even though he is the best represented composer in the Palace Songbook. This might suggest that the Songbook originated outside court circles, and it has recently been proposed that it was compiled in Salamanca as a student anthology, not a courtly collection. The high profile accorded to Encina in the Palace Songbook need not, however, tie the manuscript to Salamanca, especially in view of Encina’s penchant for dedicating his works to members of the royal family, notably the heir to the throne, Prince Juan, himself a keen amateur musician.

Most of Encina’s songs were written before he left Spain in 1499, and they represent a marked stylistic shift away from earlier pieces in the Palace Songbook (examples of which are to be found in Enrique’s Mi querer tanto vos quiere and the anonymous Harto de tanta porfía). The Encinian musical idiom, as epitomised in the love ballad Mi libertad, is essentially homophonic, the voices moving independently only in anticipation of the cadence point that clearly marks the end of each text phrase. This style was not, however, confined to the ballad, whose narrative function undoubtedly called for a simple, declamatory idiom, but was applied to the refrain song forms as in Los sospiros no sosiegan, a canción firmly in the courtly lyric tradition.

At the same time Encina, and his contemporaries serving in the royal chapels, cultivated the villancico, similar to the canción in its refrain structure (ABBA) but distinguished by themes (and probably melodies) of more popular origin. Songs such as the anonymous Passe el agoa or Dindirín, dindirín, both with curiously macaronic texts, have the character of popular melodies with simple accompaniments, perhaps reflecting older improvised traditions. Other villancicos, for example Gabriel’s La bella malmaridada, retain popular elements in the poetic refrain or estribillo (in this case the figure of the fair but unhappily married woman) and then elaborate them in courtly fashion in the subsequent coplas or verses, while retaining an essentially simple but not quite so basic musical idiom. Gabriel’s Yo creo que n’os dió Dios is altogether more refined, with its cascading scalic figures marking the end of the refrain. This mix of the popular and the courtly, of indigenous oral traditions and northern artifice, is characteristic of much of the songbook repertory, a musical equivalent of the blend of styles found in Isabelline architecture.

This blend is also apparent in the instrumental collections published during the sixteenth century in Spain. The Spanish kingdoms had long enjoyed a rich, improvised instrumental tradition, vestiges of which are to be found in the printed collections of vihuela music by Luys Milán (El maestro, 1536) and Luys de Narváez (Delphín de musica, 1538). Both were active in court circles, Narváez as a professional musician in the service of the Emperor Charles V, Milán as a courtier at the ducal court in Valencia. Their volumes are essentially tutors aimed at the wealthy amateur wishing to cultivate music, but not seeking to acquire the professional skills of improvisation. Other collections followed, including Venegas de Henestrosa’s Libro de cifra nueva (1557) in which the pieces by Fernández Palero and Julio da Modena are found. The fantasia and tiento are freely composed pieces with their roots firmly in the unnotated, improvised tradition; as the century advances these tend to draw increasingly on the compositional techniques of written vocal music in the manner of the Italian ricercar. Out of the art of improvising accompaniments to ballads, such as Paseávase el rey moro, grew another genre of supreme importance in Spanish music of the Renaissance: the variation.

01. Mi libertad en sosiego

02. A la villa voy

03. Passe el agoa

04. Harto de tanta porfía

05. Fantasia Tercer tono

06. Por las sierras de Madrid

07. Ne reminiscaris, Domine

08. Dindirín, dindirín

09. Fantasia Segundo tono

10. Ave, virgo, gratia plena

11. Yo creo que n'os dió Dios

12. Fantasia 10

13. Precor te, Domine Jesu Christe

14. Tiento

15. Los sospiros No sosiegan

16. Paseávase el rey moro

17. Mi querer tanto vos quiere

18. Fantasia 18

19. Dentro en el vergel moriré

20. Entra Mayo y sale Abril

21. Fantasia 12

22. La bella malmaridada

23. Sancta Maria

‘History is the essence of innumerable biographies’, wrote Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), while Schlegel (1772–1829) commented that ‘A historian is a prophet in reverse’. These are precisely the problems that beset any study of early music: much of the surviving music is anonymous, and because so little of it, comparatively speaking, has survived, the retrospective prophecies of music historians are based on fragmentary evidence. Consider the history of Spanish polyphonic song: no songbooks of Castilian-texted songs survive from before the end of the fifteenth century. Between them, these songbooks contain some five hundred songs; that is a fair number, one might think, but it is only the tip of the cancionero iceberg, to judge by the quantity of lyric verse dating from the period 1450–1530, the time when the first flowering of Spanish polyphonic song apparently occurred. However, these songs represent a notated repertory: there is plenty of extra-musical evidence to suggest that an improvised (or at least unwritten) song tradition existed much earlier in Spain. Any prophecies in reverse about developments in song forms, styles or themes must therefore take account of a practice we cannot hope to explore or describe.

The songbooks preserved in Madrid (the ‘Palace Songbook’), in Seville, Barcelona, Segovia and Elvas, present many unresolved mysteries, not least because they contain so many anonymous pieces. The attributions which are to be found in the songbooks explain why these manuscripts have long been associated with the households of the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. Most of the composers named there were singers who served at various times in either the Aragonese or the Castilian court chapels. Of these royal singers, Francisco de Peñalosa (c1470–1528) was undoubtedly the leading light, yet we know surprisingly little about his life. The bare facts are that he entered the Aragonese chapel in 1498, served there until the death of King Ferdinand in 1516 and subsequently joined the papal chapel in Rome before returning to Seville, where he held a canonry. There he passed his final years. It is immediately apparent from his cantus firmus Mass settings, which closely follow Franco-Netherlandish models in their subtle deployment of borrowed melodies, both sacred and secular, that he was a composer of considerable technical skill. Indeed, this is a technique that he extends, with a flourish of ingenuity, to one of his songs in the Palace Songbook. In Por las sierras de Madrid he combines four popular melodies, all well-known refrains, adding a fifth borrowing in the bass, a Latin gloss taken from the Acts of the Apostles, which punningly alludes to the polytextuality of the upper voices: ‘They tell out in many languages the mighty deeds of God’.

In his motets, Peñalosa is less concerned with artifice than with an expressive projection of the texts. These are generally devotional in nature, with Marian (Sancta Maria) and penitential (Ne reminiscaris) themes predominant. Peñalosa’s approach to text-setting in his motets—surely influenced by his studies with the Sicilian humanist Lucas Marineus who taught Latin to the members of the Aragonese chapel—is largely syllabic, with due attention to the correct accentuation of the words and melismas largely restricted to the penultimate syllable of a phrase. Often entirely free of borrowed material, these motets use the phrase structure of the text as the basis for the musical framework. Peñalosa exploited this expressive freedom to the full, notably in the four-voice Precor te, Domine, a meditation on the sufferings of Christ on the Cross. Here the declamatory, homophonic sections intensify the affective character of certain passages in the text, the effect being rendered still more dramatic by the use of rests to offset these words.

Humanist tendencies are also apparent in the works of the poet, playwright and composer Juan del Encina (1468–1529/30). A little more is known of his life—his training at Salamanca, his period of service at the court of the Duke of Alba in the 1490s, and his subsequent sojourn in Rome—yet he appears never to have served in the royal chapels of Ferdinand and Isabella, even though he is the best represented composer in the Palace Songbook. This might suggest that the Songbook originated outside court circles, and it has recently been proposed that it was compiled in Salamanca as a student anthology, not a courtly collection. The high profile accorded to Encina in the Palace Songbook need not, however, tie the manuscript to Salamanca, especially in view of Encina’s penchant for dedicating his works to members of the royal family, notably the heir to the throne, Prince Juan, himself a keen amateur musician.

Most of Encina’s songs were written before he left Spain in 1499, and they represent a marked stylistic shift away from earlier pieces in the Palace Songbook (examples of which are to be found in Enrique’s Mi querer tanto vos quiere and the anonymous Harto de tanta porfía). The Encinian musical idiom, as epitomised in the love ballad Mi libertad, is essentially homophonic, the voices moving independently only in anticipation of the cadence point that clearly marks the end of each text phrase. This style was not, however, confined to the ballad, whose narrative function undoubtedly called for a simple, declamatory idiom, but was applied to the refrain song forms as in Los sospiros no sosiegan, a canción firmly in the courtly lyric tradition.

At the same time Encina, and his contemporaries serving in the royal chapels, cultivated the villancico, similar to the canción in its refrain structure (ABBA) but distinguished by themes (and probably melodies) of more popular origin. Songs such as the anonymous Passe el agoa or Dindirín, dindirín, both with curiously macaronic texts, have the character of popular melodies with simple accompaniments, perhaps reflecting older improvised traditions. Other villancicos, for example Gabriel’s La bella malmaridada, retain popular elements in the poetic refrain or estribillo (in this case the figure of the fair but unhappily married woman) and then elaborate them in courtly fashion in the subsequent coplas or verses, while retaining an essentially simple but not quite so basic musical idiom. Gabriel’s Yo creo que n’os dió Dios is altogether more refined, with its cascading scalic figures marking the end of the refrain. This mix of the popular and the courtly, of indigenous oral traditions and northern artifice, is characteristic of much of the songbook repertory, a musical equivalent of the blend of styles found in Isabelline architecture.

This blend is also apparent in the instrumental collections published during the sixteenth century in Spain. The Spanish kingdoms had long enjoyed a rich, improvised instrumental tradition, vestiges of which are to be found in the printed collections of vihuela music by Luys Milán (El maestro, 1536) and Luys de Narváez (Delphín de musica, 1538). Both were active in court circles, Narváez as a professional musician in the service of the Emperor Charles V, Milán as a courtier at the ducal court in Valencia. Their volumes are essentially tutors aimed at the wealthy amateur wishing to cultivate music, but not seeking to acquire the professional skills of improvisation. Other collections followed, including Venegas de Henestrosa’s Libro de cifra nueva (1557) in which the pieces by Fernández Palero and Julio da Modena are found. The fantasia and tiento are freely composed pieces with their roots firmly in the unnotated, improvised tradition; as the century advances these tend to draw increasingly on the compositional techniques of written vocal music in the manner of the Italian ricercar. Out of the art of improvising accompaniments to ballads, such as Paseávase el rey moro, grew another genre of supreme importance in Spanish music of the Renaissance: the variation.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads