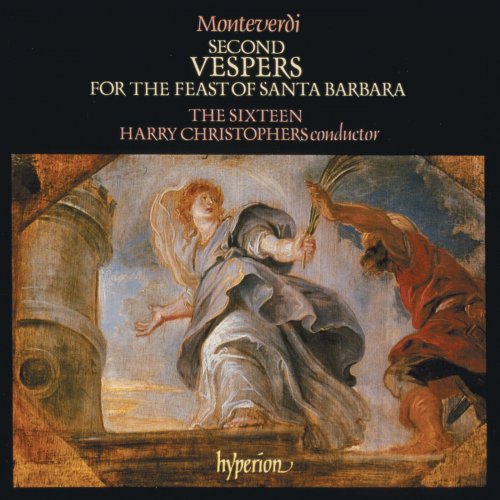

The Sixteen, Harry Christophers - Monteverdi: Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara (1988)

BAND/ARTIST: The Sixteen, Harry Christophers

- Title: Monteverdi: Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara

- Year Of Release: 1988

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:48:58

- Total Size: 397 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

CD1

01. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: I. Organ Improvisation

02. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: II. Deus in adiutorium meum intende

03. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: III. Angelicam vitam eligens

04. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: IV. Dixit Dominus Domino meo

05. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: V. Pulchra es, amica mea

06. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: VI. In Dei orto sata

07. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: VII. Laudate pueri Dominum

08. Sonata I

09. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: IX. Paterni oblita amoris

10. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: X. Laetatus sum in his

11. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XI. Nigra sum, sed formosa

12. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XII. In Sanctae Trinitatis

13. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XIII. Nisi Dominus aedificaverit domum

14. Sonata II

15. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XV. Trinitatem venerata

16. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XVI. Lauda Jerusalem

17. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XVII. Duo Seraphim clamabant

CD2

01. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XVIII. Confitebor tibi Domine

02. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XIX. Exultet celebres virginis

03. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XX. Ora pro nobis

04. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXI. Hodie beata Barbara virgo gloriosa

05. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXII. Magnificat anima mea

06. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXIII. Dominus vobiscum

07. Gaude Barbara beata

08. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXV. Sit nomen Domini benedictum

09. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXVI. Audi caelum verba mea

10. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXVII. Angelus Domini nunciavit Mariae

11. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXVIII. Sancta Barbara, ora pro nobis

12. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXIX. Ave maris stella

Monteverdi’s 1610 Vespers contains some of the best-known music of the entire Baroque period, but the composer appears to have left no indication of the occasion for which the pieces were composed. Indeed, it would seem likely that the pieces were written individually, and only form a group in our minds because they were eventually published as such. The one thing we do know is that the Vespers music was written while Monteverdi was in the service of the Duke of Mantua; it was published during a period in which he felt undervalued by the Gonzaga family, and was looking for employment elsewhere.

The reconstruction presented here is the result of a new hypothesis regarding the circumstances of composition, which I argued in full in an article in Early Music published in August 1987. Some aspects of the arrangement of the Vespers volume had always seemed rather curious to me, and I began to investigate, bearing in mind the situation in Mantua during Monteverdi’s activity there. The inclusion of a setting of Duo Seraphim had always appeared particularly problematic: its text begins with a description of the Seraphim calling to one another around the throne of God, and ends with a firm statement of faith in the doctrine of the Trinity. Clearly the statement of this dogma is of fundamental importance to Christian thought, but it has little to do with the celebration of Feasts of the Virgin Mary. The Trinitarian text of that item had always appeared to be at odds with the title-page of the publication.

This made me wonder if the dedication of the 1610 publication to the Virgin may not fully express the original intention behind the music contained in the volume. Italian religious institutions tended to put more emphasis on the celebration of local saints and festivals than on those observances which were the common property of the whole Church. In Mantua, and particularly in the Gonzaga household where Monteverdi was employed, one saint dominated all the others—Santa Barbara; she was the patron of the Gonzaga family, and the basilica within the grounds of the palace was dedicated to her honour. Because of her rare beauty Barbara had been imprisoned in a tower during her father’s absence; she was converted to Christianity, and asked the builders who were working on her tower to add a third window in honour of the Trinity. Eventually she was martyred on account of her Christian faith. The text of Duo Seraphim with its strong Trinitarian emphasis ties in well with the celebration of the Feast of Santa Barbara, and indeed two of the antiphons sung at the basilica at Second Vespers on her day refer to the doctrine of the Trinity.

Each year her festival on 4 December was celebrated in the ducal basilica with great solemnity. The preface to a collection of music published in 1613 by a later Mantuan composer, Amante Franzoni, indicates that instrumental music was heard regularly on that day. It would have been a celebration of great political importance to the Gonzaga family, for in honouring their patron worthily they were drawing attention to their own prestige as a ruling dynasty. Franzoni’s collection of 1613 contains a setting of Duo Seraphim for use on the Feast-day, showing that the text had a definite place in the musical settings performed during the celebrations. It would seem strange if the most elaborate music to emerge from the Mantuan court in that period were not employed on the Feast of the saint who was venerated more highly than any other.

The service would have opened with an adaptation of the toccata from L’Orfeo, a fanfare which seems to have possessed special ceremonial importance for the Gonzaga family. Thus the ruling family would have heard the opening call for God’s help sung to music which symbolized their power as they assembled for Vespers to honour the saint whom they regarded as their protectress.

An examination of the liturgy peculiar to the ducal basilica reveals that the psalms used at Second Vespers of Santa Barbara correspond exactly to those set by Monteverdi. Given the lack of evidence it is pointless to claim that the psalms were all composed as a cycle for one particular celebration. Indeed, they could well have been written over the course of a longer period to add grandeur to the celebrations by standing in place of the normal chant of the liturgy. The special liturgy of the ducal basilica was the product of Counter-Reformation conservatism, and it could well be that Monteverdi took the unusual step of including chants in the psalm settings in order to preserve the traditional ethos of worship there.

The Song of Songs texts Pulchra es and Nigra sum are applicable not only to Feasts of the Virgin, but also to celebrations of any female saint; they could equally well have been associated with the Feast of Santa Barbara or with the Virgin Mary. The only additional items (beyond those appropriate for Santa Barbara) are Audi caelum and Ave maris stella. Ave maris stella uses the Roman and not the Santa Barbara form of the chant, and it was not therefore expressly intended for the ducal basilica; it has been included in this recording for the sake of completely representing the 1610 publication of the Vespers music.

The Sonata sopra Sancta Maria might be thought to raise some problems, but there is evidence to show that liturgical pieces of this nature were frequently adapted to include the name of the saint whose Feast it was. In similar examples the name of the saint is left blank, or its place is marked with an ‘N’, and appropriate rubrics supplied (for instance, ‘This motet is appropriate for any saint, male or female’). Perhaps Monteverdi’s sonata was originally composed with Mary in mind, but contemporary usage shows that the substitution of one saint for another was standard practice. In this reconstruction the name of Barbara replaces that of Mary, and the familiar rhythm has been adjusted to take account of this.

Two short instrumental sonatas have been employed as antiphon substitutes. These are taken from a manuscript compiled by the Mantuan musician Giovanni Amigone in 1613. It is not certain that Amigone himself was the composer, but the pieces can certainly be numbered amongst the earliest solo sonatas for a treble instrument and continuo.

We know that Monteverdi had no official position in the ducal basilica, which employed its own staff and was independent from the secular musical establishment of the court. This separation of function surely accounts for the meagre amount of church music which Monteverdi produced during his time in the service of the Gonzaga family. During the years following L’Orfeo the ducal church underwent an unsettled period when the maestro was ill, and a satisfactory replacement was not found. The family may well have overridden their own administrative structures during such a period by commissioning their most famous musician to help maintain the standard of music in the chapel. Indeed, the mention of ‘princely chapels’ on the title-page of the 1610 publication could even be regarded as misleading if the works had never been performed in the chapel attached to the palace where he had worked for so long.

Why did Monteverdi decide to publish a Vespers ‘della Beata Vergine’, rather than alluding to the works’ origins in a dedication to Santa Barbara, if her Feast really lay behind the composition? By the time Monteverdi published the 1610 volume his relationship with the Gonzaga dynasty had been soured. He was looking for a job elsewhere and had to prove his competence as a composer. If Monteverdi had published a volume of music intended for Vespers of Santa Barbara he would have created little interest: no other institution celebrated the Feast as lavishly, and moreover he would have been adding enormously to the prestige of the family who had treated him unjustly. So much of the music was interchangeable that it was no problem for Monteverdi to publish the music with a Marian dedication: the number of religious institutions dedicated to the Virgin would have ensured a good market for the music. But Monteverdi does use his Gonzaga connection to his own advantage on the title-page of the volume: here he states that the music is appropriate for ‘Sacella sive Principum Cubicula’—the chapels and chambers of princes. The works which comprise the volume may well owe their origins to celebrations in honour of the saint to whom the princely chapel in Mantua was dedicated—Santa Barbara.

CD1

01. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: I. Organ Improvisation

02. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: II. Deus in adiutorium meum intende

03. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: III. Angelicam vitam eligens

04. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: IV. Dixit Dominus Domino meo

05. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: V. Pulchra es, amica mea

06. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: VI. In Dei orto sata

07. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: VII. Laudate pueri Dominum

08. Sonata I

09. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: IX. Paterni oblita amoris

10. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: X. Laetatus sum in his

11. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XI. Nigra sum, sed formosa

12. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XII. In Sanctae Trinitatis

13. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XIII. Nisi Dominus aedificaverit domum

14. Sonata II

15. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XV. Trinitatem venerata

16. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XVI. Lauda Jerusalem

17. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XVII. Duo Seraphim clamabant

CD2

01. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XVIII. Confitebor tibi Domine

02. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XIX. Exultet celebres virginis

03. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XX. Ora pro nobis

04. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXI. Hodie beata Barbara virgo gloriosa

05. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXII. Magnificat anima mea

06. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXIII. Dominus vobiscum

07. Gaude Barbara beata

08. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXV. Sit nomen Domini benedictum

09. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXVI. Audi caelum verba mea

10. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXVII. Angelus Domini nunciavit Mariae

11. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXVIII. Sancta Barbara, ora pro nobis

12. Vespers for the Feast of Santa Barbara: XXIX. Ave maris stella

Monteverdi’s 1610 Vespers contains some of the best-known music of the entire Baroque period, but the composer appears to have left no indication of the occasion for which the pieces were composed. Indeed, it would seem likely that the pieces were written individually, and only form a group in our minds because they were eventually published as such. The one thing we do know is that the Vespers music was written while Monteverdi was in the service of the Duke of Mantua; it was published during a period in which he felt undervalued by the Gonzaga family, and was looking for employment elsewhere.

The reconstruction presented here is the result of a new hypothesis regarding the circumstances of composition, which I argued in full in an article in Early Music published in August 1987. Some aspects of the arrangement of the Vespers volume had always seemed rather curious to me, and I began to investigate, bearing in mind the situation in Mantua during Monteverdi’s activity there. The inclusion of a setting of Duo Seraphim had always appeared particularly problematic: its text begins with a description of the Seraphim calling to one another around the throne of God, and ends with a firm statement of faith in the doctrine of the Trinity. Clearly the statement of this dogma is of fundamental importance to Christian thought, but it has little to do with the celebration of Feasts of the Virgin Mary. The Trinitarian text of that item had always appeared to be at odds with the title-page of the publication.

This made me wonder if the dedication of the 1610 publication to the Virgin may not fully express the original intention behind the music contained in the volume. Italian religious institutions tended to put more emphasis on the celebration of local saints and festivals than on those observances which were the common property of the whole Church. In Mantua, and particularly in the Gonzaga household where Monteverdi was employed, one saint dominated all the others—Santa Barbara; she was the patron of the Gonzaga family, and the basilica within the grounds of the palace was dedicated to her honour. Because of her rare beauty Barbara had been imprisoned in a tower during her father’s absence; she was converted to Christianity, and asked the builders who were working on her tower to add a third window in honour of the Trinity. Eventually she was martyred on account of her Christian faith. The text of Duo Seraphim with its strong Trinitarian emphasis ties in well with the celebration of the Feast of Santa Barbara, and indeed two of the antiphons sung at the basilica at Second Vespers on her day refer to the doctrine of the Trinity.

Each year her festival on 4 December was celebrated in the ducal basilica with great solemnity. The preface to a collection of music published in 1613 by a later Mantuan composer, Amante Franzoni, indicates that instrumental music was heard regularly on that day. It would have been a celebration of great political importance to the Gonzaga family, for in honouring their patron worthily they were drawing attention to their own prestige as a ruling dynasty. Franzoni’s collection of 1613 contains a setting of Duo Seraphim for use on the Feast-day, showing that the text had a definite place in the musical settings performed during the celebrations. It would seem strange if the most elaborate music to emerge from the Mantuan court in that period were not employed on the Feast of the saint who was venerated more highly than any other.

The service would have opened with an adaptation of the toccata from L’Orfeo, a fanfare which seems to have possessed special ceremonial importance for the Gonzaga family. Thus the ruling family would have heard the opening call for God’s help sung to music which symbolized their power as they assembled for Vespers to honour the saint whom they regarded as their protectress.

An examination of the liturgy peculiar to the ducal basilica reveals that the psalms used at Second Vespers of Santa Barbara correspond exactly to those set by Monteverdi. Given the lack of evidence it is pointless to claim that the psalms were all composed as a cycle for one particular celebration. Indeed, they could well have been written over the course of a longer period to add grandeur to the celebrations by standing in place of the normal chant of the liturgy. The special liturgy of the ducal basilica was the product of Counter-Reformation conservatism, and it could well be that Monteverdi took the unusual step of including chants in the psalm settings in order to preserve the traditional ethos of worship there.

The Song of Songs texts Pulchra es and Nigra sum are applicable not only to Feasts of the Virgin, but also to celebrations of any female saint; they could equally well have been associated with the Feast of Santa Barbara or with the Virgin Mary. The only additional items (beyond those appropriate for Santa Barbara) are Audi caelum and Ave maris stella. Ave maris stella uses the Roman and not the Santa Barbara form of the chant, and it was not therefore expressly intended for the ducal basilica; it has been included in this recording for the sake of completely representing the 1610 publication of the Vespers music.

The Sonata sopra Sancta Maria might be thought to raise some problems, but there is evidence to show that liturgical pieces of this nature were frequently adapted to include the name of the saint whose Feast it was. In similar examples the name of the saint is left blank, or its place is marked with an ‘N’, and appropriate rubrics supplied (for instance, ‘This motet is appropriate for any saint, male or female’). Perhaps Monteverdi’s sonata was originally composed with Mary in mind, but contemporary usage shows that the substitution of one saint for another was standard practice. In this reconstruction the name of Barbara replaces that of Mary, and the familiar rhythm has been adjusted to take account of this.

Two short instrumental sonatas have been employed as antiphon substitutes. These are taken from a manuscript compiled by the Mantuan musician Giovanni Amigone in 1613. It is not certain that Amigone himself was the composer, but the pieces can certainly be numbered amongst the earliest solo sonatas for a treble instrument and continuo.

We know that Monteverdi had no official position in the ducal basilica, which employed its own staff and was independent from the secular musical establishment of the court. This separation of function surely accounts for the meagre amount of church music which Monteverdi produced during his time in the service of the Gonzaga family. During the years following L’Orfeo the ducal church underwent an unsettled period when the maestro was ill, and a satisfactory replacement was not found. The family may well have overridden their own administrative structures during such a period by commissioning their most famous musician to help maintain the standard of music in the chapel. Indeed, the mention of ‘princely chapels’ on the title-page of the 1610 publication could even be regarded as misleading if the works had never been performed in the chapel attached to the palace where he had worked for so long.

Why did Monteverdi decide to publish a Vespers ‘della Beata Vergine’, rather than alluding to the works’ origins in a dedication to Santa Barbara, if her Feast really lay behind the composition? By the time Monteverdi published the 1610 volume his relationship with the Gonzaga dynasty had been soured. He was looking for a job elsewhere and had to prove his competence as a composer. If Monteverdi had published a volume of music intended for Vespers of Santa Barbara he would have created little interest: no other institution celebrated the Feast as lavishly, and moreover he would have been adding enormously to the prestige of the family who had treated him unjustly. So much of the music was interchangeable that it was no problem for Monteverdi to publish the music with a Marian dedication: the number of religious institutions dedicated to the Virgin would have ensured a good market for the music. But Monteverdi does use his Gonzaga connection to his own advantage on the title-page of the volume: here he states that the music is appropriate for ‘Sacella sive Principum Cubicula’—the chapels and chambers of princes. The works which comprise the volume may well owe their origins to celebrations in honour of the saint to whom the princely chapel in Mantua was dedicated—Santa Barbara.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads