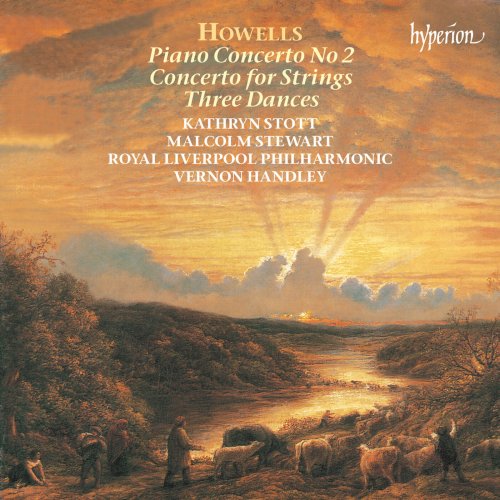

Kathryn Stott, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, Vernon Handley - Herbert Howells: Concertos & Dances (1992)

BAND/ARTIST: Kathryn Stott, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, Vernon Handley

- Title: Herbert Howells: Concertos & Dances

- Year Of Release: 1992

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:09:17

- Total Size: 250 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Concerto for String Orchestra: I. Allegro, assai vivace

02. Concerto for String Orchestra: II. Quasi lento. Teneramente

03. Concerto for String Orchestra: III. Allegro vivo. Ritmico e giocoso

04. 3 Dances for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 7: I. Giocoso molto

05. 3 Dances for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 7: II. Quasi lento, quieto

06. 3 Dances for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 7: III. Molto allegro

07. Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor: I. Allegro. Hard and Bright

08. Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor: II. Poco lento, calmato

09. Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor: III. Allegro. Hard and Bright Again

What a sea change there has been in public opinion in the last ten years or so which has made the recording of the music here not only possible but desirable. Two of the works had not been heard between their first performances (Three Dances, 1915; Piano Concerto, 1925) and 1989 when the present writer put together a Howells ‘Composer of the Week’ series on Radio 3, concentrating for the first time on the orchestral music. It was a revelation.

Herbert Howells was the most brilliant student of his generation at the Royal College of Music and was dubbed his ‘son in music’ by the notoriously difficult Sir Charles Stanford, his composition teacher. Sir Arthur Bliss, who went to the RCM a year after Howells having done a music degree at Cambridge, remembers: ‘Howells had the outstanding talent. His quickly written scores, showing a beautifully resolute calligraphy, with their technical maturity simply disheartened me. I had to learn one of the most painful lessons of my life, that there are others who are born with more gifts than oneself; no amount of self-confidence can at heart convince one to the contrary.’

What is the reason for the neglect over so many years of almost all of Howells’s orchestral music? The answer, perhaps, is twofold. First, Howells was notoriously sensitive to criticism. An adverse word from any source would trigger the immediate withdrawal of a work from circulation. Why this was so is difficult to say. Probably the answer lies in his being put on a pedestal by Stanford where he was led to believe that everything he did was good. When subsequently he was prey to the whims and prejudices of the lions’ den of the critical press he did not have the inner self-confidence and strength to cope with their claws. Secondly, where he once said ‘there’s no room for symphonic lengths these days’ (feeling, perhaps, that the concert-going public’s attention span was not capable of taking a major new symphonic work), in reality it was not his way and that this was just what the public did want.

Of the three works recorded here, two – the Piano Concerto and the Concerto for string orchestra – are major three-movement works. The Three Dances, on the other hand, are delightful miniatures, written in 1915 in relatively carefree student days (relatively, because the Great War was already a year old though Howells, through ill health which nearly killed him in 1917, was exempted from active service). They were composed for a young fellow-student George Whittaker, a highly gifted violinist who had entered the College aged only eleven. Certainly the music has no hint of the momentous events beginning to take shape and which would fundamentally affect one of his closest friends, Ivor Gurney, and kill a number of others. The dances are, in fact, extremely sunny pieces, not yet imbued with the Howellsian pathos which grew to dominate his mode of speech. To this end they are as yet uncharacteristic, speaking more of his teacher’s influence than of his own intuitive nature which was still to come to its maturity. Putting that aside, however, what lovely pieces they are. The first (Giocoso molto), quite big-scale, is almost a gypsy dance with some brilliantly colourful orchestration laid out for large forces. In the manuscript Howells writes at the end that he finished the score in bed; it is nice to know that student habits don’t change over the years.

The second dance (Quasi lento, quieto) has one of the most beguiling tunes of the period. To some extent it is the change in his later music away from writing a tune to creating long-breathed, melismatic phrases, which creates the aural problem for the unsophisticated listener who wants the ‘anchorage’ which a regular-metre melody gives. Here, though, there is no problem. Why this dance alone did not become a classic ‘pop’ of the period is difficult to understand, though it is probably bound up with Howells’s reticence and his impatience, as a student, to be getting on with the next project.

The last dance (Molto allegro) is, by contrast, short and furious, providing an exquisite foil to the others. Here is Howells, already, aged only twenty-three, a consummately skilled orchestrator, a highly gifted creator of atmosphere (one of the most important features of his mature style) and having a considerable skill with both form and melody.

Ten years on from the composition of these dances Howells was a familiar name. He had been thrust into the limelight in 1916 with the publication of his Piano Quartet in A minor under the auspices of the Carnegie Trust. Amongst the seven composers chosen to have works published, Howells’s was the only unknown name, and his was the only piece of chamber music; his was also the first to be published.

In these early years it appeared that nothing could stop Howells’s meteoric rise to stardom. Music flowed from him in an unstoppable flood of inspiration; orchestral works, a remarkable series of chamber works including three string quartets and a clarinet quintet, music for piano, for organ, three violin sonatas, solo songs including King David – one of the classics of the period – and works for chorus and orchestra including at the behest of Elgar a 1922 Gloucester Three Choirs Festival commission, Sine nomine.

Then came a commission from the Royal Philharmonic Society for a performance in the Queen’s Hall, London in 1925, the Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor. Sargent was to conduct (his debut with the Society) and Harold Samuel (famous for his Bach recitals) was to be soloist. The first signs of a problem arose when Samuel received the score and found that he heartily disliked the work. The composer Howard Ferguson, who was a pupil of Samuel’s and lived in his house at the time, remembers helping Samuel to learn the work by being the ‘orchestra’ on a second piano. He recalls that Samuel tried to get the Society to release him from the engagement; they refused, and the performance went ahead as planned.

It was a mark of Howells’s burgeoning reputation that the performance was widely anticipated in London musical circles and that the programme in which it was placed included recent works by composers of the previous generation – Vaughan Williams’s Pastoral Symphony, Ireland’s Mai Dun, and music by Bax and Berners. However, the performance was to all intents and purposes a disaster. Certainly, for Howells, it contained the seeds of self-destruction. As a critic noted: ‘Our Royal and ancient Philharmonic Society has given many first performances of works by the world’s greatest musicians, but the event to which I refer was specially remarkable because at the conclusion of the concerto there was the usual spontaneous applause, but on this occasion mixed with angry shouts of disapproval from one gentleman in the audience. For a few seconds there was a shocked silence, and then the applause broke out with a renewed force as a sort of counter-protest against the unseemly conduct of the gentleman who evidently did not like music of a modernity unpalatable to his taste.’

The reception of this work caused Howells to freeze as a composer. Although the concerto was at proof-stage with the publishers he instantly withdrew it and virtually stopped composing for some ten years, writing in the interim only very small-scale pieces and revising some early compositions.

All this was, of course, a huge overreaction to a histrionic display which, in any country other than England, would have been regarded as par for the course and merely amusing. To the oversensitive Howells, though, it was a nightmare. Late in the composer’s life the pianist Hilary Macnamara persuaded him to have another look at it. He began revising the work but soon put it aside again.

The concerto is a big-scale, three-movement work, designed on a very unusual ground plan (which was possibly what led to the outburst). Howells organized the three movements as a huge sonata-form structure with the first movement acting as the exposition, the slow movement as the development, and the last movement as a modified recapitulation (all the movements are linked). To this extent the constant referral back to the first subject (a short, diatonic tune) can become monotonous unless sympathetically interpreted. The problems at the first performance were exacerbated by unsympathetic performers. This must have come across to any with ears to hear.

In describing the form of the work, Howells also hints at something deeper which was to become such a hallmark of his style later on: ‘What always matters to a modern is to express a complex mood. Now for that, sonata form is not always suitable, or sonata form as hitherto accepted.’ This ‘complex mood’ was something which Vaughan Williams brought to perfection in his utterly original Pastoral Symphony. Howells described this more fully in a penetrating article in Music and Letters in April 1922: ‘He neither depicts nor describes. It is not his concern to “make the universe his box of toys”. He builds up a great mood, insistent to an unusual degree, but having in itself far more variety than a merely slight acquaintance with it would suggest. In matter and manner it is entirely personal … you may not like the Symphony’s frame of mind; but there it is, strong and courageous; it is the truth of the work, and out of it would naturally arise whatever risk it has run of being publicly cold-shouldered.’

Howells’s Piano Concerto No 2 is full of drama and lyricism. He intended it to be a ‘diatonic affair, with deliberate tunes all the way … jolly in feeling, and attempting to get to the point as quickly as maybe’. Certainly it is a tour de force and is quite unlike any other concerto of the period. With its brilliant use of the orchestra and its colourful effects it must have sounded very modern indeed to that audience on 27 April 1925.

In 1935 Howells’s only son died of polio, aged only nine. It was another and far more devastating moment in his life. Emotionally paralysed for some time, he began to pick up composition again as a means of purging the ghost of his son. Before the boy’s death Howells had been composing a work for string orchestra to commemorate the recent death of Elgar. In 1938 he completed it, giving it the title Concerto for string orchestra. Not all of it was new: the first movement was an extensive reworking of the ebullient Preludio from an early string orchestra suite of 1917, the second movement of which became a separate work – the Elegy for viola, string quartet and strings, one of the composer’s most beautiful orchestral works. The second movement jointly commemorates Elgar and Michael Howells. Howells called it ‘submissive and memorial in its intention and purpose’. The third movement balances the first in its energy and drive.

Howells described the inspiration behind the work: ‘It was meant to be a modest expression of the abiding spell of music for strings, and to be, in that genus, in humble relationship to two supreme works, Vaughan Williams’s ‘Tallis’ Fantasia, and Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro. In 1910 at the Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester Cathedral I was present at the first performance of the Fantasia. Within days, and for the first time, I heard the Introduction and Allegro. I was at the time 17; deeply impressionable. 25 years later, again at Gloucester, walking with Sir Edward Elgar in the cathedral precincts, he talked quietly and earnestly of the technique of writing for strings. One name dominated his talk, George Frederick Handel.’

The death of Howells’s son ironically unlocked the frozen powers which had stopped him composing after the debacle of the second piano concerto. He went on to write his undisputed masterpiece, Hymnus Paradisi, and the whole emphasis of his work shifted from music for the concert hall to music either for the church, or choral music with non-liturgical religious texts such as the Stabat mater written in the mid fifties. This (the church music) is the music by which he is best known. Recordings such as this serve to redress the imbalance which has existed for years in the appreciation of Howells’s output by giving us the opportunity to reassess these major orchestral scores through which Howells’s career developed and his musical personality reached maturity.

01. Concerto for String Orchestra: I. Allegro, assai vivace

02. Concerto for String Orchestra: II. Quasi lento. Teneramente

03. Concerto for String Orchestra: III. Allegro vivo. Ritmico e giocoso

04. 3 Dances for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 7: I. Giocoso molto

05. 3 Dances for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 7: II. Quasi lento, quieto

06. 3 Dances for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 7: III. Molto allegro

07. Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor: I. Allegro. Hard and Bright

08. Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor: II. Poco lento, calmato

09. Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor: III. Allegro. Hard and Bright Again

What a sea change there has been in public opinion in the last ten years or so which has made the recording of the music here not only possible but desirable. Two of the works had not been heard between their first performances (Three Dances, 1915; Piano Concerto, 1925) and 1989 when the present writer put together a Howells ‘Composer of the Week’ series on Radio 3, concentrating for the first time on the orchestral music. It was a revelation.

Herbert Howells was the most brilliant student of his generation at the Royal College of Music and was dubbed his ‘son in music’ by the notoriously difficult Sir Charles Stanford, his composition teacher. Sir Arthur Bliss, who went to the RCM a year after Howells having done a music degree at Cambridge, remembers: ‘Howells had the outstanding talent. His quickly written scores, showing a beautifully resolute calligraphy, with their technical maturity simply disheartened me. I had to learn one of the most painful lessons of my life, that there are others who are born with more gifts than oneself; no amount of self-confidence can at heart convince one to the contrary.’

What is the reason for the neglect over so many years of almost all of Howells’s orchestral music? The answer, perhaps, is twofold. First, Howells was notoriously sensitive to criticism. An adverse word from any source would trigger the immediate withdrawal of a work from circulation. Why this was so is difficult to say. Probably the answer lies in his being put on a pedestal by Stanford where he was led to believe that everything he did was good. When subsequently he was prey to the whims and prejudices of the lions’ den of the critical press he did not have the inner self-confidence and strength to cope with their claws. Secondly, where he once said ‘there’s no room for symphonic lengths these days’ (feeling, perhaps, that the concert-going public’s attention span was not capable of taking a major new symphonic work), in reality it was not his way and that this was just what the public did want.

Of the three works recorded here, two – the Piano Concerto and the Concerto for string orchestra – are major three-movement works. The Three Dances, on the other hand, are delightful miniatures, written in 1915 in relatively carefree student days (relatively, because the Great War was already a year old though Howells, through ill health which nearly killed him in 1917, was exempted from active service). They were composed for a young fellow-student George Whittaker, a highly gifted violinist who had entered the College aged only eleven. Certainly the music has no hint of the momentous events beginning to take shape and which would fundamentally affect one of his closest friends, Ivor Gurney, and kill a number of others. The dances are, in fact, extremely sunny pieces, not yet imbued with the Howellsian pathos which grew to dominate his mode of speech. To this end they are as yet uncharacteristic, speaking more of his teacher’s influence than of his own intuitive nature which was still to come to its maturity. Putting that aside, however, what lovely pieces they are. The first (Giocoso molto), quite big-scale, is almost a gypsy dance with some brilliantly colourful orchestration laid out for large forces. In the manuscript Howells writes at the end that he finished the score in bed; it is nice to know that student habits don’t change over the years.

The second dance (Quasi lento, quieto) has one of the most beguiling tunes of the period. To some extent it is the change in his later music away from writing a tune to creating long-breathed, melismatic phrases, which creates the aural problem for the unsophisticated listener who wants the ‘anchorage’ which a regular-metre melody gives. Here, though, there is no problem. Why this dance alone did not become a classic ‘pop’ of the period is difficult to understand, though it is probably bound up with Howells’s reticence and his impatience, as a student, to be getting on with the next project.

The last dance (Molto allegro) is, by contrast, short and furious, providing an exquisite foil to the others. Here is Howells, already, aged only twenty-three, a consummately skilled orchestrator, a highly gifted creator of atmosphere (one of the most important features of his mature style) and having a considerable skill with both form and melody.

Ten years on from the composition of these dances Howells was a familiar name. He had been thrust into the limelight in 1916 with the publication of his Piano Quartet in A minor under the auspices of the Carnegie Trust. Amongst the seven composers chosen to have works published, Howells’s was the only unknown name, and his was the only piece of chamber music; his was also the first to be published.

In these early years it appeared that nothing could stop Howells’s meteoric rise to stardom. Music flowed from him in an unstoppable flood of inspiration; orchestral works, a remarkable series of chamber works including three string quartets and a clarinet quintet, music for piano, for organ, three violin sonatas, solo songs including King David – one of the classics of the period – and works for chorus and orchestra including at the behest of Elgar a 1922 Gloucester Three Choirs Festival commission, Sine nomine.

Then came a commission from the Royal Philharmonic Society for a performance in the Queen’s Hall, London in 1925, the Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor. Sargent was to conduct (his debut with the Society) and Harold Samuel (famous for his Bach recitals) was to be soloist. The first signs of a problem arose when Samuel received the score and found that he heartily disliked the work. The composer Howard Ferguson, who was a pupil of Samuel’s and lived in his house at the time, remembers helping Samuel to learn the work by being the ‘orchestra’ on a second piano. He recalls that Samuel tried to get the Society to release him from the engagement; they refused, and the performance went ahead as planned.

It was a mark of Howells’s burgeoning reputation that the performance was widely anticipated in London musical circles and that the programme in which it was placed included recent works by composers of the previous generation – Vaughan Williams’s Pastoral Symphony, Ireland’s Mai Dun, and music by Bax and Berners. However, the performance was to all intents and purposes a disaster. Certainly, for Howells, it contained the seeds of self-destruction. As a critic noted: ‘Our Royal and ancient Philharmonic Society has given many first performances of works by the world’s greatest musicians, but the event to which I refer was specially remarkable because at the conclusion of the concerto there was the usual spontaneous applause, but on this occasion mixed with angry shouts of disapproval from one gentleman in the audience. For a few seconds there was a shocked silence, and then the applause broke out with a renewed force as a sort of counter-protest against the unseemly conduct of the gentleman who evidently did not like music of a modernity unpalatable to his taste.’

The reception of this work caused Howells to freeze as a composer. Although the concerto was at proof-stage with the publishers he instantly withdrew it and virtually stopped composing for some ten years, writing in the interim only very small-scale pieces and revising some early compositions.

All this was, of course, a huge overreaction to a histrionic display which, in any country other than England, would have been regarded as par for the course and merely amusing. To the oversensitive Howells, though, it was a nightmare. Late in the composer’s life the pianist Hilary Macnamara persuaded him to have another look at it. He began revising the work but soon put it aside again.

The concerto is a big-scale, three-movement work, designed on a very unusual ground plan (which was possibly what led to the outburst). Howells organized the three movements as a huge sonata-form structure with the first movement acting as the exposition, the slow movement as the development, and the last movement as a modified recapitulation (all the movements are linked). To this extent the constant referral back to the first subject (a short, diatonic tune) can become monotonous unless sympathetically interpreted. The problems at the first performance were exacerbated by unsympathetic performers. This must have come across to any with ears to hear.

In describing the form of the work, Howells also hints at something deeper which was to become such a hallmark of his style later on: ‘What always matters to a modern is to express a complex mood. Now for that, sonata form is not always suitable, or sonata form as hitherto accepted.’ This ‘complex mood’ was something which Vaughan Williams brought to perfection in his utterly original Pastoral Symphony. Howells described this more fully in a penetrating article in Music and Letters in April 1922: ‘He neither depicts nor describes. It is not his concern to “make the universe his box of toys”. He builds up a great mood, insistent to an unusual degree, but having in itself far more variety than a merely slight acquaintance with it would suggest. In matter and manner it is entirely personal … you may not like the Symphony’s frame of mind; but there it is, strong and courageous; it is the truth of the work, and out of it would naturally arise whatever risk it has run of being publicly cold-shouldered.’

Howells’s Piano Concerto No 2 is full of drama and lyricism. He intended it to be a ‘diatonic affair, with deliberate tunes all the way … jolly in feeling, and attempting to get to the point as quickly as maybe’. Certainly it is a tour de force and is quite unlike any other concerto of the period. With its brilliant use of the orchestra and its colourful effects it must have sounded very modern indeed to that audience on 27 April 1925.

In 1935 Howells’s only son died of polio, aged only nine. It was another and far more devastating moment in his life. Emotionally paralysed for some time, he began to pick up composition again as a means of purging the ghost of his son. Before the boy’s death Howells had been composing a work for string orchestra to commemorate the recent death of Elgar. In 1938 he completed it, giving it the title Concerto for string orchestra. Not all of it was new: the first movement was an extensive reworking of the ebullient Preludio from an early string orchestra suite of 1917, the second movement of which became a separate work – the Elegy for viola, string quartet and strings, one of the composer’s most beautiful orchestral works. The second movement jointly commemorates Elgar and Michael Howells. Howells called it ‘submissive and memorial in its intention and purpose’. The third movement balances the first in its energy and drive.

Howells described the inspiration behind the work: ‘It was meant to be a modest expression of the abiding spell of music for strings, and to be, in that genus, in humble relationship to two supreme works, Vaughan Williams’s ‘Tallis’ Fantasia, and Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro. In 1910 at the Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester Cathedral I was present at the first performance of the Fantasia. Within days, and for the first time, I heard the Introduction and Allegro. I was at the time 17; deeply impressionable. 25 years later, again at Gloucester, walking with Sir Edward Elgar in the cathedral precincts, he talked quietly and earnestly of the technique of writing for strings. One name dominated his talk, George Frederick Handel.’

The death of Howells’s son ironically unlocked the frozen powers which had stopped him composing after the debacle of the second piano concerto. He went on to write his undisputed masterpiece, Hymnus Paradisi, and the whole emphasis of his work shifted from music for the concert hall to music either for the church, or choral music with non-liturgical religious texts such as the Stabat mater written in the mid fifties. This (the church music) is the music by which he is best known. Recordings such as this serve to redress the imbalance which has existed for years in the appreciation of Howells’s output by giving us the opportunity to reassess these major orchestral scores through which Howells’s career developed and his musical personality reached maturity.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads