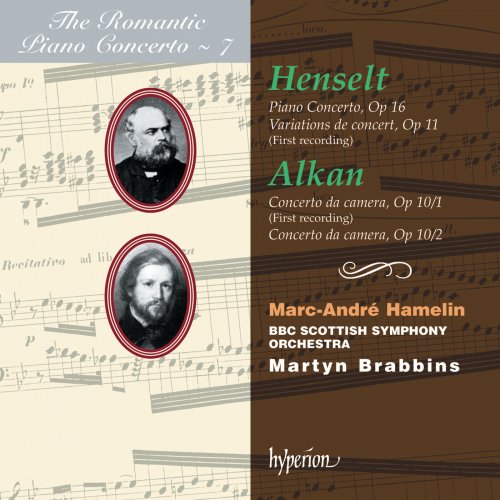

Marc-Andre Hamelin, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Martyn Brabbins - Alkan & Henselt: Piano Concertos (Hyperion Romantic Piano Concerto 7) (1994)

BAND/ARTIST: Marc-Andre Hamelin, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Martyn Brabbins

- Title: Alkan & Henselt: Piano Concertos (Hyperion Romantic Piano Concerto 7)

- Year Of Release: 1994

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:09:56

- Total Size: 216 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Piano Concerto in F Minor, Op. 16: I. Allegro patetico – Religioso – Reprise

02. Piano Concerto in F Minor, Op. 16: II. Larghetto

03. Piano Concerto in F Minor, Op. 16: III. Allegro agitato

04. Variations de concert, Op. 11: I. Introduzione. Larghetto ma non troppo

05. Variations de concert, Op. 11: II. Theme. Moderato

06. Variations de concert, Op. 11: III. Var. 1. Grazioso assai

07. Variations de concert, Op. 11: IV. Var. 2. Un poco più lento e sostenuto

08. Variations de concert, Op. 11: V. Var. 3. Scherzando

09. Variations de concert, Op. 11: VI. Var. 4. Con fuoco e pomposo

10. Variations de concert, Op. 11: VII. Var. 5. Vivace ma non troppo

11. Variations de concert, Op. 11: VIII. Adagio – Cadenza

12. Variations de concert, Op. 11: IX. Finale. Allegro vivace

13. Concerto da camera in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 10 No. 2: I. Allegro moderato

14. Concerto da camera in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 10 No. 2: II. Adagio

15. Concerto da camera in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 10 No. 2: III. Tempo I

16. Concerto da camera in A Minor, Op. 10 No. 1: I. Allegro moderato

17. Concerto da camera in A Minor, Op. 10 No. 1: II. Adagio

18. Concerto da camera in A Minor, Op. 10 No. 1: III. Rondo. Allegro

The coupling of works by Alkan and Henselt is not as arbitrary as might appear. Born six months apart, both enjoyed long lives and died within eighteen months of each other; both have been entirely overshadowed by their more illustrious contemporaries Liszt and Chopin (to the extent that they have been assigned to the footnotes of musical history), though both had an individual approach to the piano with a style as clearly defined and as idiosyncratic as their two peers; both were recluses, rarely playing their works in public; both were transcendent technicians, exploring the potential of their instrument in ways which were to influence other pianists and composers of piano music; both were eccentrics in their personal habits and lifestyles; both have been almost universally ignored by the majority of concert pianists; and neither of their names is known to the general music-loving public. (Although there has been a marked revival of interest in Alkan’s work over the past three decades, there is still only grudging acknowledgement of his importance from the musical ‘establishment’.)

The four works presented here were all written at around the same time – that is to say the twelve or so years between 1832 and 1844. Only one of them has ever featured in the regular repertoire of any pianist; Alkan’s Concerto No 1 probably has not been realized in this its original form since its initial performances; Henselt’s Meyerbeer variations have certainly not been performed by anyone this century (its publishers Breitkopf and Härtel confirmed this when checking their archives); Alkan’s Concerto No 2 has been recorded before, notably by Michael Ponti, who was also responsible for one of only two previous recordings of the Henselt concerto.

Of the myriad contributions to the genre written during the first part of the nineteenth century, Henselt’s Piano Concerto in F minor, Op 16, is the one whose neglect is the hardest to explain. It has the composer’s individual stamp on every bar, it is original in its writing (if not its structure), its orchestration is more than adequate and at times masterly, its themes are varied and memorable, the musical and technical challenges for the soloist are equalled only by their effect on the listener, and the whole work has the feel of white-hot inspiration. Henselt never reached the same height again. Is it a good piece of music? Yes. The piece may not offer revolutionary concepts (indeed, much of it is firmly rooted in the past), but that does not alter its intrinsic merit. It should be part of the core repertoire.

Where did it come from? What was the genesis of this most demanding of Romantic concertos? Its composer was born on 9 May 1814 at Schwabach, a small town in Bavaria, close to Nuremberg. His father Philipp Eduard Henselt is described variously as a cotton manufacturer or cotton weaver, whose marriage to Caroline Geigenmüller produced six children. When Adolf was three the family moved to Munich. It was not a musical family but he had his first piano lessons at the age of five, gave his first public recital when he was fifteen and, in 1831, under the auspices of King Ludwig I of Bavaria, was granted a stipend to study piano in Weimar with Hummel and composition in Vienna with the master theorist and pedagogue Simon Sechter.

The early part of his career progressed conventionally enough, though his elopement with (and eventual marriage to) the wife of one of Goethe’s friends must have raised a few eyebrows at the time. Aristocratic in looks and bearing, he would in later years resemble the Emperor Franz Josef. His early success touring Germany and Russia was underlined by the reception of his sets of studies (Opp 2 & 5) published in 1837 and 1838. The Douze études caractéristiques de concert (Op 2) were dedicated to his royal patron and include the best (only?) known work of Henselt today – ‘Si oiseau j’étais, à toi je volerais’ (‘Were I a bird, I’d fly to you’), a tricky feather-light study in sixths once given the distinction of a recording by Rachmaninov. These were followed by the Douze études de salon (dedicated to HRH Marie the Queen of Saxony) which, with the previous set of twelve, alternate through all the major and minor keys.

These studies attracted a lot of attention for the young virtuoso, many of them presenting technical problems different from those in Chopin’s two sets (published a few years previously) but still maintaining the new concept of exercises wrapped in poetry. They were Henselt’s ‘calling card’ and to the present day remain beyond the capabilities of many pianists. Even the legendary Anton Rubinstein had to admit defeat; after working on the études and F minor Concerto for a few days, he realized ‘it was a waste of time, for they were based on an abnormal formation of the hand. In this respect, Henselt, like Paganini, was a freak.’ Many passages in the études presage the harmonic progressions and technical difficulties of the F minor Concerto. There is a liberal use of chords of the tenth (sometimes twelfth) and arpeggios with a larger stretch than an octave. It wasn’t that Henselt had large hands – au contraire, he is known to have had small hands with short fleshy fingers. But by means of diligent, self-consuming practice he managed to achieve an amazing degree of elasticity with an extension that could reach C–E–G–C–F in his left hand and B–E–A–C–E in the right (try it!)...

01. Piano Concerto in F Minor, Op. 16: I. Allegro patetico – Religioso – Reprise

02. Piano Concerto in F Minor, Op. 16: II. Larghetto

03. Piano Concerto in F Minor, Op. 16: III. Allegro agitato

04. Variations de concert, Op. 11: I. Introduzione. Larghetto ma non troppo

05. Variations de concert, Op. 11: II. Theme. Moderato

06. Variations de concert, Op. 11: III. Var. 1. Grazioso assai

07. Variations de concert, Op. 11: IV. Var. 2. Un poco più lento e sostenuto

08. Variations de concert, Op. 11: V. Var. 3. Scherzando

09. Variations de concert, Op. 11: VI. Var. 4. Con fuoco e pomposo

10. Variations de concert, Op. 11: VII. Var. 5. Vivace ma non troppo

11. Variations de concert, Op. 11: VIII. Adagio – Cadenza

12. Variations de concert, Op. 11: IX. Finale. Allegro vivace

13. Concerto da camera in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 10 No. 2: I. Allegro moderato

14. Concerto da camera in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 10 No. 2: II. Adagio

15. Concerto da camera in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 10 No. 2: III. Tempo I

16. Concerto da camera in A Minor, Op. 10 No. 1: I. Allegro moderato

17. Concerto da camera in A Minor, Op. 10 No. 1: II. Adagio

18. Concerto da camera in A Minor, Op. 10 No. 1: III. Rondo. Allegro

The coupling of works by Alkan and Henselt is not as arbitrary as might appear. Born six months apart, both enjoyed long lives and died within eighteen months of each other; both have been entirely overshadowed by their more illustrious contemporaries Liszt and Chopin (to the extent that they have been assigned to the footnotes of musical history), though both had an individual approach to the piano with a style as clearly defined and as idiosyncratic as their two peers; both were recluses, rarely playing their works in public; both were transcendent technicians, exploring the potential of their instrument in ways which were to influence other pianists and composers of piano music; both were eccentrics in their personal habits and lifestyles; both have been almost universally ignored by the majority of concert pianists; and neither of their names is known to the general music-loving public. (Although there has been a marked revival of interest in Alkan’s work over the past three decades, there is still only grudging acknowledgement of his importance from the musical ‘establishment’.)

The four works presented here were all written at around the same time – that is to say the twelve or so years between 1832 and 1844. Only one of them has ever featured in the regular repertoire of any pianist; Alkan’s Concerto No 1 probably has not been realized in this its original form since its initial performances; Henselt’s Meyerbeer variations have certainly not been performed by anyone this century (its publishers Breitkopf and Härtel confirmed this when checking their archives); Alkan’s Concerto No 2 has been recorded before, notably by Michael Ponti, who was also responsible for one of only two previous recordings of the Henselt concerto.

Of the myriad contributions to the genre written during the first part of the nineteenth century, Henselt’s Piano Concerto in F minor, Op 16, is the one whose neglect is the hardest to explain. It has the composer’s individual stamp on every bar, it is original in its writing (if not its structure), its orchestration is more than adequate and at times masterly, its themes are varied and memorable, the musical and technical challenges for the soloist are equalled only by their effect on the listener, and the whole work has the feel of white-hot inspiration. Henselt never reached the same height again. Is it a good piece of music? Yes. The piece may not offer revolutionary concepts (indeed, much of it is firmly rooted in the past), but that does not alter its intrinsic merit. It should be part of the core repertoire.

Where did it come from? What was the genesis of this most demanding of Romantic concertos? Its composer was born on 9 May 1814 at Schwabach, a small town in Bavaria, close to Nuremberg. His father Philipp Eduard Henselt is described variously as a cotton manufacturer or cotton weaver, whose marriage to Caroline Geigenmüller produced six children. When Adolf was three the family moved to Munich. It was not a musical family but he had his first piano lessons at the age of five, gave his first public recital when he was fifteen and, in 1831, under the auspices of King Ludwig I of Bavaria, was granted a stipend to study piano in Weimar with Hummel and composition in Vienna with the master theorist and pedagogue Simon Sechter.

The early part of his career progressed conventionally enough, though his elopement with (and eventual marriage to) the wife of one of Goethe’s friends must have raised a few eyebrows at the time. Aristocratic in looks and bearing, he would in later years resemble the Emperor Franz Josef. His early success touring Germany and Russia was underlined by the reception of his sets of studies (Opp 2 & 5) published in 1837 and 1838. The Douze études caractéristiques de concert (Op 2) were dedicated to his royal patron and include the best (only?) known work of Henselt today – ‘Si oiseau j’étais, à toi je volerais’ (‘Were I a bird, I’d fly to you’), a tricky feather-light study in sixths once given the distinction of a recording by Rachmaninov. These were followed by the Douze études de salon (dedicated to HRH Marie the Queen of Saxony) which, with the previous set of twelve, alternate through all the major and minor keys.

These studies attracted a lot of attention for the young virtuoso, many of them presenting technical problems different from those in Chopin’s two sets (published a few years previously) but still maintaining the new concept of exercises wrapped in poetry. They were Henselt’s ‘calling card’ and to the present day remain beyond the capabilities of many pianists. Even the legendary Anton Rubinstein had to admit defeat; after working on the études and F minor Concerto for a few days, he realized ‘it was a waste of time, for they were based on an abnormal formation of the hand. In this respect, Henselt, like Paganini, was a freak.’ Many passages in the études presage the harmonic progressions and technical difficulties of the F minor Concerto. There is a liberal use of chords of the tenth (sometimes twelfth) and arpeggios with a larger stretch than an octave. It wasn’t that Henselt had large hands – au contraire, he is known to have had small hands with short fleshy fingers. But by means of diligent, self-consuming practice he managed to achieve an amazing degree of elasticity with an extension that could reach C–E–G–C–F in his left hand and B–E–A–C–E in the right (try it!)...

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads