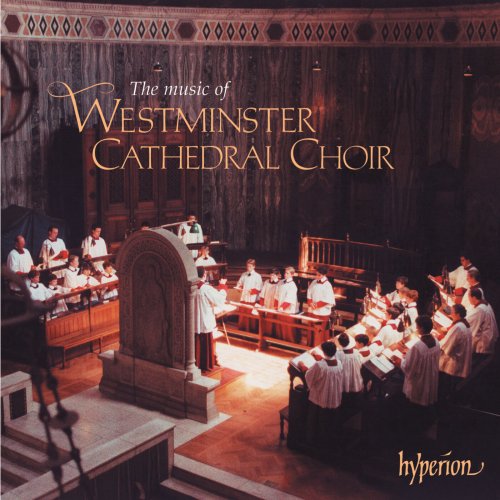

Westminster Cathedral Choir & James O'Donnell - The Music of Westminster Cathedral Choir (2023)

BAND/ARTIST: Westminster Cathedral Choir, James O'Donnell, Andrew Reid, Iain Simcock

- Title: The Music of Westminster Cathedral Choir

- Year Of Release: 1998 / 2023

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks + booklet)

- Total Time: 1:19:28

- Total Size: 311 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Great Is the Lord, Op. 67

02. Missa brevis, Op. 63: III-IV. Sanctus, Benedictus & Agnus Dei

03. Omnes gentes, plaudite manibus

04. Super flumina Babylonis

05. O sacrum convivium

06. Mass in G Major, FP 89: III. Sanctus

07. Westminster Mass: III. Deus, Deus meus

08. Ave verum corpus

09. Mass for Double Choir: V. Agnus Dei

10. Ave verum corpus, T. 92

11. Hei mihi, Domine

12. Nunc dimittis, H. 127

13. Ave Maria, Op. 23 No. 2, MWV B19

14. Magnificat for 8-Part Chorus, Op. 164

01. Great Is the Lord, Op. 67

02. Missa brevis, Op. 63: III-IV. Sanctus, Benedictus & Agnus Dei

03. Omnes gentes, plaudite manibus

04. Super flumina Babylonis

05. O sacrum convivium

06. Mass in G Major, FP 89: III. Sanctus

07. Westminster Mass: III. Deus, Deus meus

08. Ave verum corpus

09. Mass for Double Choir: V. Agnus Dei

10. Ave verum corpus, T. 92

11. Hei mihi, Domine

12. Nunc dimittis, H. 127

13. Ave Maria, Op. 23 No. 2, MWV B19

14. Magnificat for 8-Part Chorus, Op. 164

When Cardinal Herbert Vaughan, Archbishop of Westminster, founded the new Roman Catholic Cathedral near Victoria in central London, a vital part of his vision was the establishment of a fine choir of men and boys, modelled on the classic English Cathedral choral foundations, which would sing for the liturgy every day. In this way, the Cathedral would incorporate the highest standards of church music together with an authoritative observance of the Roman rite in a way unrivalled by any other church in the world.

The foundation stone of J F Bentley’s Byzantine-influenced red-brick cathedral was laid in 1895. By the time it opened for services in 1903, both founder and architect had died, but the newly-established cathedral choir, complete with its residential choir school in the precincts and an inspirational Master of Music, Richard Runciman Terry, had already been rehearsing and building up an extensive repertory for a year. The interior decoration of the building may not have been started, let alone finished (to this day it is incomplete), but the choir was well-established by the time it sang its first Mass in the cathedral.

The appointment of the right director of music had been critical, and it was by happy chance that Cardinal Vaughan had encountered Terry, under whose direction the choir of the Benedictine school at Downside Abbey had developed a reputation for the revival of some of the great polyphonic works of Byrd, Taverner, Tallis and others, most of which had not been sung for centuries. Upon his appointment at Westminster, Terry immediately set about establishing a breathtakingly ambitious programme of choral music with Renaissance polyphony and Gregorian chant as the two focal points. In doing so, he closely followed the teachings of Pope Pius X who, in his Motu proprio of 1903, had laid down that pride of place in the liturgical music of the Roman Catholic Church should be given to plainsong and the great corpus of polyphonic music. The resonant spaces and austere magnificence of Bentley’s architecture perfectly suited this approach, and the liturgical music at Westminster soon became an exemplar to Catholic church musicians all over the world. In addition, Terry commissioned a large amount of new sacred music from composers—particularly younger composers—he deemed suitable for the task: Herbert Howells composed settings of the four Marian antiphons, Holst his Nunc dimittis; Vaughan Williams’s Mass in G minor was given its first liturgical performance in Westminster Cathedral.

Public interest and curiosity in the great ceremonies in the strange new cathedral was considerable. Musicians became aware that this was the only place they could hear, day by day, the lost masterpieces of the sixteenth century, recovered from the library and restored to life in their proper context. Teachers such as Stanford urged their pupils to attend choral services simply to have the chance to hear this newly-rediscovered repertory (“Palestrina for twopence”, as he said—the price of the bus fare from the Royal College of Music to Westminster Cathedral). The press regularly sent correspondents to describe the ceremonies for their readers. Terry’s colleagues in church-music and scholarly circles stood back in awe as he ploughed his way through music—especially that of English composers of the Tudor period—which had not seen the light of day for hundreds of years. He did not do things by halves: Terry transcribed and performed the complete Cantiones sacrae of Peter Philips, the complete Gradualia of Byrd. He made recordings, the first probably in 1908. He was editor-in-chief of Tudor Church Music and knighted in 1922. It is probably true to say that, under Terry, the Choir of Westminster Cathedral was the best-known and most highly-regarded of all the English cathedral and collegiate choirs at that time. But the pace proved impossible to sustain, and Terry resigned in 1924. After his departure the Choir’s fortunes sadly and rapidly waned under the direction of a succession of lesser figures.

When George Malcolm was appointed Master of Music in 1947, his first task was to re-establish the choir after the hiatus caused by the war. Quickly he put into effect his unorthodox views on training boys’ voices which once more put Westminster Cathedral Choir ‘on the map’ and which, while provoking considerable controversy among traditionalists, have since had a profound effect on the training of boys’ voices in England. Malcolm sought a strikingly direct, forward and bright sound which shocked as many listeners as it delighted. Among the latter, Benjamin Britten was so impressed by the forthright and ‘un-Anglican’ sound of the Westminster boys that he offered to write a new Mass for them: the Missa Brevis in D (completed just before George Malcolm left the Cathedral in 1959) was the happy result.

During the 1960s the Roman Catholic Church went through the exhilarating and sometimes painful upheaval of the Second Vatican Council. Westminster Cathedral, as an important Catholic flagship, was inevitably affected by the liturgical reforms and, at one point, the very existence of the Choir came under grave threat. The appointment of Abbot Basil Hume as Archbishop of Westminster in 1976 led to a renewal of commitment to the Choir and a determination to put it on a sound financial basis, a policy which the Cathedral authorities are still actively pursuing. Since that period, under successive Masters of Music Stephen Cleobury and David Hill, the Choir returned to a position of considerable prominence and repute in the musical world which the current Master of Music (since 1988), James O’Donnell, has consolidated and maintained.

The Choir’s raison d’être has always been to sing at the celebration of Mass and the Divine Office in the cathedral, and it continues to fulfil this duty to this day. Indeed, it is thought to be the only choir in the world which sings a fully-choral Mass every day. Much of the Choir’s current repertory would have been familiar to Sir Richard Terry, but it is continually being expanded and renewed with the addition of newly-commissioned works. Alongside its liturgical duties the Choir has given many concerts in Britain and overseas, and has made many broadcasts on television and radio. Central to its current standing has been the Choir’s long and fruitful relationship with Hyperion Records, and a notably broad and ever-expanding catalogue of recordings which have received the highest international acclaim, with many prizes from British and international critics. In 1984 the choir’s recording of Victoria’s Missa O quam gloriosum under David Hill won the Gramophone Early Music Award. The recording of Martin’s Mass for double choir and Pizzetti’s Requiem under James O’Donnell has now won the 1998 Gramophone Award for Best Choral Recording of the year.

It is easy to forget that Edward Elgar, that quintessentially English composer, was a devout Roman Catholic and that most of his early sacred choral works were composed for his own Church. Like his Tudor Catholic forebears, however, Elgar was adept at catering for the needs of the Church of England. This disc begins with one of his two great Psalm-settings, Great is the Lord. It was composed in 1912 for a service in Westminster Abbey marking the 250th anniversary of The Royal Society, and is a setting of Psalm 48. Like its companion work, Give unto the Lord (1914) which sets Psalm 29, it exists in a fully-orchestrated version as well as one, recorded here, for organ and choir. Great is the Lord was written within two years of the Violin Concerto (1910) and echoes of that great work can be detected in its material. It is a direct and dramatic response to the text, constructed rather like a small cantata, with a most affecting central baritone solo in the distant key of A flat (the tonic is D), and some pictorial word-setting. The opening theme, which returns majestically at the end, is of immense grandeur and nobility.

Benjamin Britten, like Elgar, wrote prolifically for choirs, including much sacred music, all of which was conceived for the Anglican Church with the exception of the Missa Brevis in D, composed in 1959 for the boys of Westminster Cathedral Choir at the suggestion of George Malcolm. Britten had been impressed by their 1958 performance of his A Ceremony of Carols (a work later recorded on Hyperion CDA66220, directed by David Hill) and offered to write a piece for them. The request was for a short Mass for boys’ voices and organ suitable for use during the week. Accordingly the music is concentrated and economic, based on simple motifs which are used with brilliant resourcefulness. The two movements included here, Sanctus and Agnus Dei, are prime examples of this: the former is based on a sweepingly powerful twelve-note theme, cleverly divided between the three vocal parts before being heard in the organ part; the latter is set in an uneasy 54 metre over a sinister ground bass on top of which the text is sung to a sinuous and lamenting chromatic motif. Between the two movements comes the Benedictus, an imitative duet for treble and alto soloists over a quasi-pizzicato organ accompaniment.

Two works from the sixteenth century follow. Christopher Tye composed his Omnes gentes, plaudite manibus, a setting of Psalm 46 (47), during the short reign of the Catholic Queen Mary in the 1550s (although Tye himself was Anglican and ordained a priest late in life). The motet is a vigorous and virtuosic setting of the text and uses the five voices with variety and imagination.

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina is often regarded as the archetypal polyphonist of the Roman school, and his famous setting of Super flumina Babylonis (published in 1581) is a classic example of his art: each phrase of text is set with characterized music which flows directly from the meaning of the words and yet achieves a remarkable degree of musical cohesion and growth. The vocal scoring is precisely imagined: one particularly fine moment is the alto lead to the words ‘In salicibus in medio eius’ which emerges beautifully from within the choir and carries the music forward into its affecting final section.

With Olivier Messiaen’s only published liturgical choral work, his 1937 setting of the Eucharistic antiphon O sacrum convivium, we enter a new sound-world: completely still, rapt in meditation and uninterested in ‘development’ of material, but merely in adoration and contemplation of what Messiaen profoundly believed to be the eternal truths of the Catholic faith. He wrote no more liturgical music because he believed that Gregorian chant was the perfect sacred music. This motet is based in the warm and rich key of F sharp major (which Liszt and others associated with the Divine). The same slightly lopsided rhythm is used repeatedly, giving the work a hypnotic and lilting forward movement. It builds to an ecstatic climax and then winds down during the final serene ‘Alleluia’ towards a close on Messiaen’s beloved added-sixth chord.

Francis Poulenc was another devoutly Catholic French composer, and composed his brilliant and unusual Mass in G major at about the same time as Messiaen composed O sacrum convivium. Poulenc had, in effect, rediscovered his faith in the wake of a tragic motor accident in which a close friend had died, and he was inspired to compose a series of sacred choral works, among which was the Mass. If Britten’s Sanctus hints at the power and majesty of the heavenly throng, Poulenc’s angels seem to be dancing on tiptoes with barely-contained, almost childlike joy. The final Hosanna then surprises with its suddenly unleashed power and massive block chords.

The young British composer Roxanna Panufnik was commissioned to write a Mass to celebrate the 75th birthday of Cardinal Basil Hume, Archbishop of Westminster. The result, Westminster Mass, was first performed liturgically on Ascension Day in 1998. Although the Mass itself is scored for string orchestra, two harps and tubular bells, there is a central movement, recorded here, for unaccompanied choir and treble soloist which sets Psalm 62 (63) in a mixture of Latin and English. The still, tonal centres of the work, coloured by juxtaposition of major and minor harmonies and delicate changes of harmonic focus, create an atmospheric setting of the words, which were selected specially by Cardinal Hume.

The effective setting of the Eucharistic hymn Ave verum corpus by Colin Mawby is one of a large number of choral works he composed while Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral from 1962 to 1976. Mawby had been a chorister in the Cathedral Choir under George Malcolm and had shown early promise as an organist. He now lives and works in Ireland and devotes almost all his time to composition.

The Swiss composer Frank Martin wrote his Mass for unaccompanied double choir in 1922, adding the Agnus Dei included on this disc four years later. He kept the manuscript of this great work hidden in a drawer for some forty years and it was not performed until 1963, since when its stature as one of the greatest twentieth-century choral works has been recognized. It seems that Martin, a man of deep religious faith, felt that his Mass was too personal a statement to be exposed to public view. The Agnus Dei is a deeply moving setting in which the two choirs are essentially independent of one another, the second choir singing the text in equal notes homophonically while the first sings in unison a freer melody, full of supple syncopation and ever-varied. After a heart-rending climax the tension subsides and the movement closes with a serene invocation of peace.

William Byrd trod a delicate path between the Churches of England and Rome, composing much liturgical music for both but remaining a staunch member of the latter throughout his life, despite the dangers—at some periods considerable—to himself and his family. No doubt his prominence as a composer and his position as sometime Gentleman and later Organist of the Chapel Royal stood him in good stead with the authorities. But, even so, Byrd took increasingly greater risks with his unequivocally Catholic publications, culminating in 1605 and 1607 with the Gradualia, a comprehensive musical setting of the Roman Propers for the major feasts of the year. The Ave verum corpus, while not part of this collection, is one of Byrd’s most celebrated sacred works: deceptively simple and restrained, but also balanced and poised and exhibiting a masterly control of harmony and choral texture.

The music of Francisco Guerrero has been eclipsed by that of his younger countryman Tomás Luis de Victoria, but in his own time he was regarded as the leading Spanish composer, and was certainly the most influential musical figure during the time of Philip II. He was for many years maestro de capilla at Seville Cathedral and composed prolifically, producing over a hundred motets and two volumes of Masses. Hei mihi, Domine is a fine example of Guerrero’s refined technique and imaginative word-setting, each phrase new and distinctively characterized, and with subtle harmonic inflections which give this penitential work its intense atmosphere.

Gustav Holst’s Nunc dimittis (1915) was one of the many works commissioned for use in Westminster Cathedral by Richard Terry. The manuscript was lost for some years and the work rediscovered only recently. It is a fine setting of the Canticle of Simeon for eight-part unaccompanied choir. The opening is particularly effective: the first word ‘Nunc’ emerges voice by voice from the lowest part upwards, the harmony shifting slightly as it does so: it is almost as if the listener becomes gradually aware of the chord hanging in mid-air. Such an impressionistic and bold effect must have been very striking during the Office of Compline as darkness was falling in the incense-filled Cathedral.

Settings of the Ave Maria are many and various: it is surely one of the most popular texts for musical treatment. Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy’s imaginative setting displays the easy and attractive fluency of all his music. It is set for tenor soloist, choir and organ and is the second of Three Sacred Pieces, Op 23. The opening, lilting solo melody, which is taken up in turn by the choir, returns in the final section, enhanced by interjections from other solo voices. The central section, ‘Sancta Maria’, gives the organ a continuo-style ‘walking’ bass part, over which music of greater intensity and contrapuntal complexity unfolds.

The Magnificat for eight-part chorus, Op 164, by Charles Villiers Stanford, was finished in 1918. Its apparent opulence and brilliance belie a rather sad background. It was composed in the shadow of the First World War (in which several of Stanford’s pupils were killed or injured) and in the wake of a serious rift with his close friend, Parry. By the time they had been reconciled, and Stanford had completed his Magnificat as a token of his friendship, Parry had died. Stanford’s dedication inscribed the work: ‘This work, which death prevented me from giving Charles Hubert Hastings Parry in life, I dedicate to his name in grief.’ Notwithstanding this sad postscript, the piece itself is full of joy, variety and brilliant polychoral effects. The opening and closing sections seem to pay conscious tribute to Bach’s Magnificat, and the vitality of the choral writing throughout the work sweeps the listener along as it drives towards its majestic peroration.

The appointment of the right director of music had been critical, and it was by happy chance that Cardinal Vaughan had encountered Terry, under whose direction the choir of the Benedictine school at Downside Abbey had developed a reputation for the revival of some of the great polyphonic works of Byrd, Taverner, Tallis and others, most of which had not been sung for centuries. Upon his appointment at Westminster, Terry immediately set about establishing a breathtakingly ambitious programme of choral music with Renaissance polyphony and Gregorian chant as the two focal points. In doing so, he closely followed the teachings of Pope Pius X who, in his Motu proprio of 1903, had laid down that pride of place in the liturgical music of the Roman Catholic Church should be given to plainsong and the great corpus of polyphonic music. The resonant spaces and austere magnificence of Bentley’s architecture perfectly suited this approach, and the liturgical music at Westminster soon became an exemplar to Catholic church musicians all over the world. In addition, Terry commissioned a large amount of new sacred music from composers—particularly younger composers—he deemed suitable for the task: Herbert Howells composed settings of the four Marian antiphons, Holst his Nunc dimittis; Vaughan Williams’s Mass in G minor was given its first liturgical performance in Westminster Cathedral.

Public interest and curiosity in the great ceremonies in the strange new cathedral was considerable. Musicians became aware that this was the only place they could hear, day by day, the lost masterpieces of the sixteenth century, recovered from the library and restored to life in their proper context. Teachers such as Stanford urged their pupils to attend choral services simply to have the chance to hear this newly-rediscovered repertory (“Palestrina for twopence”, as he said—the price of the bus fare from the Royal College of Music to Westminster Cathedral). The press regularly sent correspondents to describe the ceremonies for their readers. Terry’s colleagues in church-music and scholarly circles stood back in awe as he ploughed his way through music—especially that of English composers of the Tudor period—which had not seen the light of day for hundreds of years. He did not do things by halves: Terry transcribed and performed the complete Cantiones sacrae of Peter Philips, the complete Gradualia of Byrd. He made recordings, the first probably in 1908. He was editor-in-chief of Tudor Church Music and knighted in 1922. It is probably true to say that, under Terry, the Choir of Westminster Cathedral was the best-known and most highly-regarded of all the English cathedral and collegiate choirs at that time. But the pace proved impossible to sustain, and Terry resigned in 1924. After his departure the Choir’s fortunes sadly and rapidly waned under the direction of a succession of lesser figures.

When George Malcolm was appointed Master of Music in 1947, his first task was to re-establish the choir after the hiatus caused by the war. Quickly he put into effect his unorthodox views on training boys’ voices which once more put Westminster Cathedral Choir ‘on the map’ and which, while provoking considerable controversy among traditionalists, have since had a profound effect on the training of boys’ voices in England. Malcolm sought a strikingly direct, forward and bright sound which shocked as many listeners as it delighted. Among the latter, Benjamin Britten was so impressed by the forthright and ‘un-Anglican’ sound of the Westminster boys that he offered to write a new Mass for them: the Missa Brevis in D (completed just before George Malcolm left the Cathedral in 1959) was the happy result.

During the 1960s the Roman Catholic Church went through the exhilarating and sometimes painful upheaval of the Second Vatican Council. Westminster Cathedral, as an important Catholic flagship, was inevitably affected by the liturgical reforms and, at one point, the very existence of the Choir came under grave threat. The appointment of Abbot Basil Hume as Archbishop of Westminster in 1976 led to a renewal of commitment to the Choir and a determination to put it on a sound financial basis, a policy which the Cathedral authorities are still actively pursuing. Since that period, under successive Masters of Music Stephen Cleobury and David Hill, the Choir returned to a position of considerable prominence and repute in the musical world which the current Master of Music (since 1988), James O’Donnell, has consolidated and maintained.

The Choir’s raison d’être has always been to sing at the celebration of Mass and the Divine Office in the cathedral, and it continues to fulfil this duty to this day. Indeed, it is thought to be the only choir in the world which sings a fully-choral Mass every day. Much of the Choir’s current repertory would have been familiar to Sir Richard Terry, but it is continually being expanded and renewed with the addition of newly-commissioned works. Alongside its liturgical duties the Choir has given many concerts in Britain and overseas, and has made many broadcasts on television and radio. Central to its current standing has been the Choir’s long and fruitful relationship with Hyperion Records, and a notably broad and ever-expanding catalogue of recordings which have received the highest international acclaim, with many prizes from British and international critics. In 1984 the choir’s recording of Victoria’s Missa O quam gloriosum under David Hill won the Gramophone Early Music Award. The recording of Martin’s Mass for double choir and Pizzetti’s Requiem under James O’Donnell has now won the 1998 Gramophone Award for Best Choral Recording of the year.

It is easy to forget that Edward Elgar, that quintessentially English composer, was a devout Roman Catholic and that most of his early sacred choral works were composed for his own Church. Like his Tudor Catholic forebears, however, Elgar was adept at catering for the needs of the Church of England. This disc begins with one of his two great Psalm-settings, Great is the Lord. It was composed in 1912 for a service in Westminster Abbey marking the 250th anniversary of The Royal Society, and is a setting of Psalm 48. Like its companion work, Give unto the Lord (1914) which sets Psalm 29, it exists in a fully-orchestrated version as well as one, recorded here, for organ and choir. Great is the Lord was written within two years of the Violin Concerto (1910) and echoes of that great work can be detected in its material. It is a direct and dramatic response to the text, constructed rather like a small cantata, with a most affecting central baritone solo in the distant key of A flat (the tonic is D), and some pictorial word-setting. The opening theme, which returns majestically at the end, is of immense grandeur and nobility.

Benjamin Britten, like Elgar, wrote prolifically for choirs, including much sacred music, all of which was conceived for the Anglican Church with the exception of the Missa Brevis in D, composed in 1959 for the boys of Westminster Cathedral Choir at the suggestion of George Malcolm. Britten had been impressed by their 1958 performance of his A Ceremony of Carols (a work later recorded on Hyperion CDA66220, directed by David Hill) and offered to write a piece for them. The request was for a short Mass for boys’ voices and organ suitable for use during the week. Accordingly the music is concentrated and economic, based on simple motifs which are used with brilliant resourcefulness. The two movements included here, Sanctus and Agnus Dei, are prime examples of this: the former is based on a sweepingly powerful twelve-note theme, cleverly divided between the three vocal parts before being heard in the organ part; the latter is set in an uneasy 54 metre over a sinister ground bass on top of which the text is sung to a sinuous and lamenting chromatic motif. Between the two movements comes the Benedictus, an imitative duet for treble and alto soloists over a quasi-pizzicato organ accompaniment.

Two works from the sixteenth century follow. Christopher Tye composed his Omnes gentes, plaudite manibus, a setting of Psalm 46 (47), during the short reign of the Catholic Queen Mary in the 1550s (although Tye himself was Anglican and ordained a priest late in life). The motet is a vigorous and virtuosic setting of the text and uses the five voices with variety and imagination.

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina is often regarded as the archetypal polyphonist of the Roman school, and his famous setting of Super flumina Babylonis (published in 1581) is a classic example of his art: each phrase of text is set with characterized music which flows directly from the meaning of the words and yet achieves a remarkable degree of musical cohesion and growth. The vocal scoring is precisely imagined: one particularly fine moment is the alto lead to the words ‘In salicibus in medio eius’ which emerges beautifully from within the choir and carries the music forward into its affecting final section.

With Olivier Messiaen’s only published liturgical choral work, his 1937 setting of the Eucharistic antiphon O sacrum convivium, we enter a new sound-world: completely still, rapt in meditation and uninterested in ‘development’ of material, but merely in adoration and contemplation of what Messiaen profoundly believed to be the eternal truths of the Catholic faith. He wrote no more liturgical music because he believed that Gregorian chant was the perfect sacred music. This motet is based in the warm and rich key of F sharp major (which Liszt and others associated with the Divine). The same slightly lopsided rhythm is used repeatedly, giving the work a hypnotic and lilting forward movement. It builds to an ecstatic climax and then winds down during the final serene ‘Alleluia’ towards a close on Messiaen’s beloved added-sixth chord.

Francis Poulenc was another devoutly Catholic French composer, and composed his brilliant and unusual Mass in G major at about the same time as Messiaen composed O sacrum convivium. Poulenc had, in effect, rediscovered his faith in the wake of a tragic motor accident in which a close friend had died, and he was inspired to compose a series of sacred choral works, among which was the Mass. If Britten’s Sanctus hints at the power and majesty of the heavenly throng, Poulenc’s angels seem to be dancing on tiptoes with barely-contained, almost childlike joy. The final Hosanna then surprises with its suddenly unleashed power and massive block chords.

The young British composer Roxanna Panufnik was commissioned to write a Mass to celebrate the 75th birthday of Cardinal Basil Hume, Archbishop of Westminster. The result, Westminster Mass, was first performed liturgically on Ascension Day in 1998. Although the Mass itself is scored for string orchestra, two harps and tubular bells, there is a central movement, recorded here, for unaccompanied choir and treble soloist which sets Psalm 62 (63) in a mixture of Latin and English. The still, tonal centres of the work, coloured by juxtaposition of major and minor harmonies and delicate changes of harmonic focus, create an atmospheric setting of the words, which were selected specially by Cardinal Hume.

The effective setting of the Eucharistic hymn Ave verum corpus by Colin Mawby is one of a large number of choral works he composed while Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral from 1962 to 1976. Mawby had been a chorister in the Cathedral Choir under George Malcolm and had shown early promise as an organist. He now lives and works in Ireland and devotes almost all his time to composition.

The Swiss composer Frank Martin wrote his Mass for unaccompanied double choir in 1922, adding the Agnus Dei included on this disc four years later. He kept the manuscript of this great work hidden in a drawer for some forty years and it was not performed until 1963, since when its stature as one of the greatest twentieth-century choral works has been recognized. It seems that Martin, a man of deep religious faith, felt that his Mass was too personal a statement to be exposed to public view. The Agnus Dei is a deeply moving setting in which the two choirs are essentially independent of one another, the second choir singing the text in equal notes homophonically while the first sings in unison a freer melody, full of supple syncopation and ever-varied. After a heart-rending climax the tension subsides and the movement closes with a serene invocation of peace.

William Byrd trod a delicate path between the Churches of England and Rome, composing much liturgical music for both but remaining a staunch member of the latter throughout his life, despite the dangers—at some periods considerable—to himself and his family. No doubt his prominence as a composer and his position as sometime Gentleman and later Organist of the Chapel Royal stood him in good stead with the authorities. But, even so, Byrd took increasingly greater risks with his unequivocally Catholic publications, culminating in 1605 and 1607 with the Gradualia, a comprehensive musical setting of the Roman Propers for the major feasts of the year. The Ave verum corpus, while not part of this collection, is one of Byrd’s most celebrated sacred works: deceptively simple and restrained, but also balanced and poised and exhibiting a masterly control of harmony and choral texture.

The music of Francisco Guerrero has been eclipsed by that of his younger countryman Tomás Luis de Victoria, but in his own time he was regarded as the leading Spanish composer, and was certainly the most influential musical figure during the time of Philip II. He was for many years maestro de capilla at Seville Cathedral and composed prolifically, producing over a hundred motets and two volumes of Masses. Hei mihi, Domine is a fine example of Guerrero’s refined technique and imaginative word-setting, each phrase new and distinctively characterized, and with subtle harmonic inflections which give this penitential work its intense atmosphere.

Gustav Holst’s Nunc dimittis (1915) was one of the many works commissioned for use in Westminster Cathedral by Richard Terry. The manuscript was lost for some years and the work rediscovered only recently. It is a fine setting of the Canticle of Simeon for eight-part unaccompanied choir. The opening is particularly effective: the first word ‘Nunc’ emerges voice by voice from the lowest part upwards, the harmony shifting slightly as it does so: it is almost as if the listener becomes gradually aware of the chord hanging in mid-air. Such an impressionistic and bold effect must have been very striking during the Office of Compline as darkness was falling in the incense-filled Cathedral.

Settings of the Ave Maria are many and various: it is surely one of the most popular texts for musical treatment. Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy’s imaginative setting displays the easy and attractive fluency of all his music. It is set for tenor soloist, choir and organ and is the second of Three Sacred Pieces, Op 23. The opening, lilting solo melody, which is taken up in turn by the choir, returns in the final section, enhanced by interjections from other solo voices. The central section, ‘Sancta Maria’, gives the organ a continuo-style ‘walking’ bass part, over which music of greater intensity and contrapuntal complexity unfolds.

The Magnificat for eight-part chorus, Op 164, by Charles Villiers Stanford, was finished in 1918. Its apparent opulence and brilliance belie a rather sad background. It was composed in the shadow of the First World War (in which several of Stanford’s pupils were killed or injured) and in the wake of a serious rift with his close friend, Parry. By the time they had been reconciled, and Stanford had completed his Magnificat as a token of his friendship, Parry had died. Stanford’s dedication inscribed the work: ‘This work, which death prevented me from giving Charles Hubert Hastings Parry in life, I dedicate to his name in grief.’ Notwithstanding this sad postscript, the piece itself is full of joy, variety and brilliant polychoral effects. The opening and closing sections seem to pay conscious tribute to Bach’s Magnificat, and the vitality of the choral writing throughout the work sweeps the listener along as it drives towards its majestic peroration.

Year 2023 | Classical | FLAC / APE

Facebook

Twitter

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads