Singing is one of the oldest and most cherished activities of human beings, and it has taken a number of forms throughout history. In the Western classical tradition, one of its main expressions has been opera: an international phenomenon, in which national themes and identities are clearly evident, but in which some common traits are also found.

Art songs, by way of contrast, have had a different history. The ritual of the opera house is missing here; the primary setting for art songs is the salon, the private or semipublic context, and an atmosphere of refined intimacy. The approach to vocality is utterly different here with respect to opera: gifts and skills which are needed in an operatic situation become at times superfluous, if not outright harmful, when singing art songs, while other, different talents and abilities are necessary.

The repertoire of art songs has not developed uniformly throughout Europe; in the nineteenth century, there has been an extraordinary flowering in the German-speaking area, while in other regions there are fewer examples. This may be due to many reasons. Among them, there can be sociological causes, i.e. a context which favours the practice of Lied singing less than another: here, obviously, climate has some importance, and while the icy and long winters of Central Europe encourage people to stay at home and sing or play, in the Mediterranean countries outdoor activities were more successful (in the musical field, for instance, wind bands and the likes). There can be artistic reasons, such as the presence, or lack thereof, of a literary output suitable for musical settings. There can also be political reasons: for instance, vocal music in Italy was mainly operatic because Italians – prior to their country’s unification – felt the need for musical forms with a more pronounced socio-political dimension.

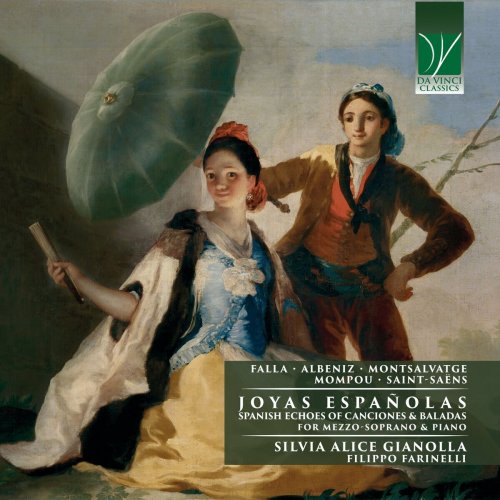

This Da Vinci Classics project gives voice to a repertoire which has the utmost historical and artistic importance, but which, at the same time, is not as commonly known as it should be. It is a repertoire of art songs revolving around Spain: around the languages of Spain (Castilian and Catalan), around the history of Spain and of its interactions with other peoples and cultures, from nearby France to the Antilles; and around Spain’s musical culture, both folk and cultivated.

Manuel de Falla is unanimously considered as one of the greatest Spanish composers; however, his career took off only slowly, and until his thirties – in spite of having already written a masterpiece such as La vida breve – he had gained very little recognition as a composer. The course of his life changed when, in 1907, at 31, he reached Paris, his longtime dream. In fact, Paris was as much of a dream for Spanish composers as was Spain for most French composers. To Spaniards, Paris offered an exceptional venue for having their works listened, commented upon, performed, appreciated; but also, on the other hand, it was a place where intellectuals met, and where anyone wishing to learn something could always find something to learn. Many of the greatest geniuses of the era lived there, at least for some time; the atmosphere was electrifying, and several musicians from Spain were fatally attracted by this exceptional context. On the other hand, however, the most important French composers of the early twentieth century were deeply and intensely fascinated by all things Spanish: Debussy was composing Ibéria, Ravel was writing Rapsodie espagnole and L’heure espagnole, and the milieu was particularly favourable for Spanish composers who had something to say.

Within this framework, de Falla wrote his Siete canciones, which are almost a Vuelta, a tour of Spain, through musical postcards. This is true even though not all melodies employed are actually drawn from the Spanish folk heritage.

De Falla summarized his approach to traditional Spanish music as follows: “Rather than literally transcribing folksongs, I have attempted to integrate their rhythm and modality, their characteristic lines and ornamental motifs, as well as their modulating cadences […]. In my humble opinion, it is more the spirit that counts in traditional song than the letter”.

De Falla dedicated this collection to Ida Godebska, whom he had met in Paris; however, the cycle would be premiered in January 1915 in Madrid, with singer Luisa Vela – who was a specialist of zarzuela and had participated in the premiere of La vida breve – and the composer at the piano. De Falla himself would later record this set with singer Maria Barrientos.

El paño moruno comes from Murcia, and its lyrics symbolically allude to the virtue of purity, which was still highly prized in brides-to-be. Interestingly, the bass line found at the beginning of this piece would be cited by de Falla himself, in an instance of self-borrowing, when he had to musically portray the “Murcian miller” in the ballet The Three-Cornered Hat.

Murcia is again represented in Seguidilla murciana, a brilliant song paced as a dance in triple time. Asturiana reveals its origins from its very name, and it is inspired by the sorrowful lamentations frequently found in that region’s music. Aragona is the protagonist of the Jota, a thrilling dance which is rendered here as a dialogue between rather brisk, lively episodes and others which are more intense and expressive. Andalusia comes once more to the fore with Nana, a lullaby of uncertain tonal characterization, purposefully playing on harmonic and tonal ambiguity. The last two pieces seem to delight in their uncertain mood. Both Canción and Polo blend a part of humour and irony with a part of seriousness, at times of despair.

Paris was the location of crucial musical experiences also for Isaac Albéniz, another of the major Spanish composers. During his stay in the French capital, Albéniz profited from the friendship and musical exchanges with Vincent d’Indy, Ernest Chausson, and later Paul Dukas and Gabriel Fauré. Manuel de Falla, in turn, would benefit from Albéniz’s generosity and his numerous ties with the Parisian community.

Albéniz’s output in terms of vocal chamber works is not extremely numerous, but it is invariably characterized by a very high quality. The set of songs recorded here, written and published in 1888, presents an instance of what we might call “reverse exoticism”. Here, the Spaniard Albéniz looks at Italy and at its poetry for inspiration. The lyrics for this set of Six Ballads were contributed by the Marquise de Bolaños, who was a much-revered member of the Madrid aristocracy. However, she was an Italian by birth, and this particular viewpoint, which probably sounded rather “exotic” in turn, seemed to intrigue the composer. Musically, Albéniz clearly took inspiration from the Italian singing style – i.e. what is known as belcanto, along with influences from the chamber vocal works by Francesco Paolo Tosti; and – especially with the benefit of hindsight – it is not difficult to see, in the polyphonic treatment of the piano part, the seeds of what would become increasingly typical for Albéniz’s compositional style. The composer was clearly fond of the set, and performed two pieces from it (Barcarola and Una rosa in dono) in public shortly after the cycle’s publication.

A different kind of exoticism is that practised by Xavier Monsalvatge i Bassols, a Catalan composer and music critic. As a child, he had been strongly encouraged (and this is an understatement) in his violin studies, even though he would have been interested in other career options as well. However, music gradually became the main focus of his professional life, while he maintained an intense engagement in other fields of life and culture. One of them was politics: his existence had been deeply marked by the Spanish Civil War, and the song cycle recorded here had been intended as a protestation manifesto against Francisco Franco’s regime.

This set of five songs originated from Monsalvatge’s childhood friendship with Mercédes Plantada, a Spanish soprano who asked the composer to contribute a work for a vocal chamber music recital she was planning to give. The composer, who was interested in Latin American poetry and in what it transmitted about the local populations and experiences, wrote first a lullaby, Canción de cuna para dormir a un negrito, on lyrics by Ildefonso Pereda Valdés. Later, moved by the extraordinary success of the piece, the composer imagined it as the centrepiece of a triptych, whereby it would have been framed by two lively pieces. The choice fell on two poems by Nicolás Guillén, Chévere and Canto negro. What should have remained a trilogy ended up as a pentalogy, however. Two other friends of the musician presented him with some of their poems: Néstor Luján, from whose works the composer selected Punto de Habanera, and Rafael Alberti, who gave him a specific poem, Cuba dentro de un piano. In Alice Henderson’s words, “By assembling these texts together, Monsalvatge uses Cinco canciones negras to make a deliberate statement about how he wished to represent Spain, Spanish America, and questions of identity that had been further emphasized by the Civil War”.

This programme is completed by two songs by Federico Mompou and one by the French composer Camille Saint-Saëns. Mompou’s songs are precisely coeval with Monsalvatge’s, both having been written in 1945. In Pastoral, the lyrics are by Juan Ramón Jiménez. Mompou treats the piano not just as an accompanying instrument, but rather as an instrument in dialogue with the voice, echoing it. In Pastoral, the piano seeks to evoke harp or guitar sounds, but it also expresses its cantabile power in the transitions between stanzas. The other song, Damunt de tu només les flors, is on lyrics by the Catalan poet Josep Janés i Olivé, and its title can be translated as “Above you, only the flowers”. Mompou’s version is masterly conceived, and the polyphony he conjures is efficacious but essential at the same time.

Finally, Saint-Saëns’ bolero provides a fitting close to this itinerary. It is a delightful, colourful piece which clearly reminisces over Bizet’s Carmen and its iconic orchestration. This song, for two voices and piano or orchestral accompaniment, had been conceived as a homage to Pauline Viardot’s daughters, who enjoyed singing it. Its lyrics are by Jules Barbier, who had written the lyrics for Saint-Saëns’ first opera, Le Timbre d’Argent. The poem’s satirical stance on Love’s Labour’s Lost is echoed by the spirited musical version, which leaves the listener intrigued and amused.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2023