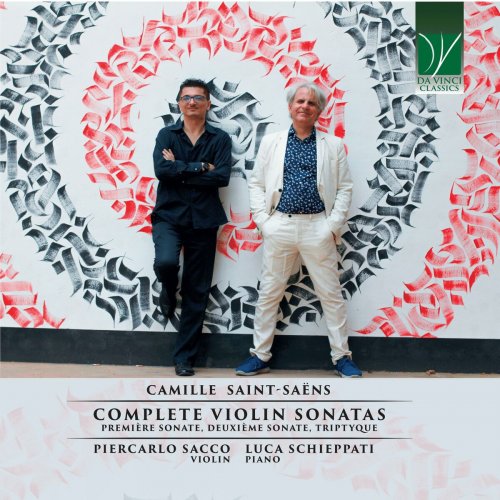

Piercarlo Sacco - Camille Saint-Saëns: Complete Violin sonatas (Première Sonate, Deuxième Sonate, Triptyque) (2023)

BAND/ARTIST: Luca Schieppati, Piercarlo Sacco

- Title: Camille Saint-Saëns: Complete Violin sonatas (Première Sonate, Deuxième Sonate, Triptyque)

- Year Of Release: 2023

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 63:21 min

- Total Size: 286 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Première Sonate in D Minor, Op. 75: I. Allegro agitato (Pour piano et violon)

02. Première Sonate in D Minor, Op. 75: II. Adagio (Pour piano et violon)

03. Première Sonate in D Minor, Op. 75: III. Allegretto moderato (Pour piano et violon)

04. Première Sonate in D Minor, Op. 75: IV. Allegro molto (Pour piano et violon)

05. Deuxième Sonate in E-Flat Major, Op. 102: I. Poco allegro più tosto moderato (Pour violon et piano)

06. Deuxième Sonate in E-Flat Major, Op. 102: II. Scherzo-Vivace (Pour violon et piano)

07. Deuxième Sonate in E-Flat Major, Op. 102: III. Andante (Pour violon et piano)

08. Deuxième Sonate in E-Flat Major, Op. 102: IV. Allegro grazioso, non presto (Pour violon et piano)

09. Triptyque, Op. 136: I. Prémice (Pour violon et piano)

10. Triptyque, Op. 136: II. Vision Congolaise (Pour violon et piano)

11. Triptyque, Op. 136: III. Joyeuseté (Pour violon et piano)

01. Première Sonate in D Minor, Op. 75: I. Allegro agitato (Pour piano et violon)

02. Première Sonate in D Minor, Op. 75: II. Adagio (Pour piano et violon)

03. Première Sonate in D Minor, Op. 75: III. Allegretto moderato (Pour piano et violon)

04. Première Sonate in D Minor, Op. 75: IV. Allegro molto (Pour piano et violon)

05. Deuxième Sonate in E-Flat Major, Op. 102: I. Poco allegro più tosto moderato (Pour violon et piano)

06. Deuxième Sonate in E-Flat Major, Op. 102: II. Scherzo-Vivace (Pour violon et piano)

07. Deuxième Sonate in E-Flat Major, Op. 102: III. Andante (Pour violon et piano)

08. Deuxième Sonate in E-Flat Major, Op. 102: IV. Allegro grazioso, non presto (Pour violon et piano)

09. Triptyque, Op. 136: I. Prémice (Pour violon et piano)

10. Triptyque, Op. 136: II. Vision Congolaise (Pour violon et piano)

11. Triptyque, Op. 136: III. Joyeuseté (Pour violon et piano)

Camille Saint-Saëns has been one of the most impressive child-prodigies in the history of music. But, different from the other members of this elite (such as Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn) his life was not as regrettably short as theirs. While none of them reached his fortieth birthday, Saint-Saëns’ career spanned over many decades. When he was born, both Mendelssohn himself and Chopin were in full activity, and the Romantic generation was still in its blooming stage. When he died, groundbreaking works of musical modernity were appearing, such as Stravinsky’s Sacre du printemps or Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. Times were changing, and with them the aesthetical climate of France and Europe in general; strands of new musical genres, such as the prodromes of jazz, were eroding the primacy of the Classical Western tradition.

Saint-Saëns’ enemies felt that his music and style were outmoded, untimely, surpassed; that he had outlived his own talent. However, the same Stravinsky who was penning the destruction of traditional music in his Sacre would later become the composer of Pulcinella; his Neoclassicism was going to endear him to the masses much more than his scandalous hammering of seemingly barbarous rhythms. Saint-Saëns was no “Neo”-classicist: he had lived the period when Mendelssohn’s Romanticism could still be suffused with the remnants of the “real”, lived Classical tradition.

Saint-Saëns had begun composing at an age when most children are unable to read or write, let alone play an instrument or creating anything innovative. His first work for violin and piano dates from 1841, when the composer was not yet five; just six months later, he wrote his first Sonata for violin and piano, a complete work in three movements, dedicated to Antoine Bessems (1806-1868), a famous Belgian violinist with whom he tried it out. This Sonata, though first in Saint-Saëns’ compositional output, did not receive the official title of “Violin Sonata no. 1”; it has been recently published but had remained in the manuscript form for nearly two centuries.

The name of “Violin Sonata no. 1” is deservedly attributed, instead, to a much later work by the French composer, recorded here together with the Second Sonata and the Triptych op. 136.

Sonata no. 1 was completed by Saint-Saëns in 1885. It is dedicated to Martin Marsick, the founder of the eponymous string quartet, with which Saint-Saëns had often played (to name but one occasion, in 1879 the Marsick Quartet and Saint-Saëns premiered César Franck’s magnificent Piano Quintet. Saint-Saëns had toured Switzerland with Marsick the year before writing this Sonata for him). Saint-Saëns had become particularly attracted by chamber music at a relatively mature age, having focused on symphonic music at an earlier stage of his compositional activity. However, he had become a zealous apostle of chamber music, co-founding with Romain Bussine, in 1871, the Société Nationale de Musique for the dissemination of French music, and most notably of chamber music.

This Sonata is in the traditional form, made of four movements; however, these four movements are coupled in pairs, to be played without intermission except that after the Adagio. This particular compositional solution was going to be employed again by Saint-Saëns in 1886, in his celebrated “Organ” Symphony.

This Sonata is less frequently played than it deserves, possibly also due to its sheer technical difficulty and musical demands; yet, these very reasons should advocate a more widespread inclusion of this splendid work in concert programmes. Virtuosity is a key element of this piece, as of many other works by Saint-Saëns, who was a very brilliant pianist and organist himself and was used to know the finest details of the performing techniques of all orchestral instruments.

The opening theme of the first movement is built on musical waves, in a thick texture interwoven with references to motifs and structural elements which will resurface throughout the Sonata. By way of contrast, the second theme is much lighter and transparent, with multicoloured refractions. Microstructural elements are in a constant interplay between the two instruments, and Saint-Saëns’ masterly handling of the compositional material is evident. His skill in the treatment of the Sonata form is amply demonstrated by the development, whereby contrapuntal techniques are abundantly employed. This doubtlessly came to Saint-Saëns from his longtime acquaintance with Baroque music (especially Bach) and organ writing.

The second movement, Adagio, which follows the first seamlessly, is dreamy and full of lyricism. The chosen form is one of the most typical for slow movements, i.e. the Lied form (ABA), with a central section marked by a powerful inspiration, in opposition to the poetic nuances of the outer parts.

After the only break in this Sonata, a gentle Scherzo, paced as an Allegretto, opens the second half of the composition. It is a rather Mendelssohnian Scherzo, with elven suggestions and transparent sounds. The enchanted atmosphere of the Scherzo, with its fantastic dimension, fades into a mystical and grave Chorale, which works as a bridge between the fairy-tale sounds of the Scherzo and the thrilling finale. Here virtuosity comes to the fore in a preponderant fashion; it is similar to a wild run, a perpetuum mobile, a whirlwind of unceasingly intermingling colours. The two instruments change places frequently, as if in a breathless chase, one performing the enthralling sequences of notes, the other punctuating them with discrete accompaniments, leading to an intoxicating close.

It has been suggested that this Sonata – or perhaps Franck’s? – might have been the hidden model for “Vinteuil’s Sonata”, the fictional musical work which is at the core of Proust’s Swann’s Way and symbolizes Mr Swann’s love for Odette. True, Proust provides the reader with a detailed description of “Vinteuil’s Sonata”, and this does not correspond to the structure of Saint-Saëns’ work; however, one of the main features of the imaginary musical piece in Proust’s text is the recurring “little phrase”, which in fact “returns” both in the literary work and in Saint-Saëns’ composition.

The First Sonata, with its utter virtuosity, clearly embodies the heroic, Romantic vocation of its composer, and the influence of such composers/performers as Franz Liszt. By way of contrast, the Second Sonata is deeply pervaded by a Neoclassical mood, with a much greater sobriety, balance, and aplomb.

The very circumstances of this Sonata’s premiere reveal something about Saint-Saëns’ exceptionally long career and how it impacted on his style, and on the reception of that style by his contemporaries. The Sonata, in fact, was premiered by Saint-Saëns himself at the piano, together with Pablo de Sarasate, the great violinist-cum-composer who had been his chamber music partner for more than three decades. The occasion for that performance was a concert at the Salle Pleyel, celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of Saint-Saëns’ first public performance (1846-1896). In that concert, the composer also premiered his Fifth Piano Concerto. A month earlier, the piece had been privately performed by two other superb artists, Eugène Ysaÿe and Raoul Pugno. The occasion of that jubilee concert was so important for Saint-Saëns that he actually “stole” the privilege of premiering the chamber music work from those who should normally have claimed rights on the premiere, i.e. the dedicatees. The Sonata had been dedicated to Léon-Alexandre Carembat and to his wife, Marie-Louise Adolphi; he was a violinist performing at the Opéra, she was a pianist, and both had been awarded a Premier Prix for their respective instruments at the Conservatoire.

The reasons for that dedication had been given by Saint-Saëns to the publisher, Durand, in the following terms: the couple had often played his chamber music works, “without letting me know in any way, whereas so many others, whenever they play anything by me, even at the end of the world, quickly send me the program with a view to laying claims to my gratitude. That did deserve a reward, I promised to do something for them, and I have kept my promise”.

This Sonata, too, is in four movements; the first is in the Sonata form, with the usual, pronounced opposition between the two themes. The first is driven by an intense emotional power, with plenty of energy; the second is much sweeter and more subdued. A curious compositional trait is that the “reconciliation” of the two themes in the recapitulation is complete: they are played together, instead of one after the other.

In this case, the Scherzo is found as the second movement, and it features a remarkable three-part canon which showcases Saint-Saëns’ extraordinary compositional ability. With a touch of pride, the composer wrote to the publisher: “I don’t think that Franck, whose canons are all praised, ever composed one as pretty as the one that forms the Trio of this scherzo, a canon that I wrote in Aswan”. In fact, the entire Sonata was written during a journey in Egypt, and it displays traits of exoticism. These are particularly evident in the slow (comparatively slow) movement, the third (Andante), where influences from Debussy can be observed, in the presence of harmonic ambiguity. This is remarkable since Saint-Saëns openly disliked Impressionism, but perhaps was not as impermeable to its suggestions as he would have loved to be. The fourth movement, in the Rondo form, is pure Saint-Saëns with an abundant presence of sense of humour and a truly Neoclassical inspiration.

Exoticism had found its way in the Second Sonata, and was abundantly present also in the Fifth Piano Concerto premiered with it (the so-called “Egyptian Concerto”). It pervades even more clearly the Triptych closing this programme. Dedicated to Elisabeth, Queen of the Belgians (but of Austrian descent), it was written in 1912. Belgium had Congo among its colonies, and the second movement of the Triptyque has in fact the title of “Vision congolaise”. The outer movements are also markedly exotic and profoundly original, showcasing the composer’s unrelenting and brilliant musical imagination, which inspired his first works for violin and piano as a child as well as those written in a very mature age.

Chiara Bertoglio

Saint-Saëns’ enemies felt that his music and style were outmoded, untimely, surpassed; that he had outlived his own talent. However, the same Stravinsky who was penning the destruction of traditional music in his Sacre would later become the composer of Pulcinella; his Neoclassicism was going to endear him to the masses much more than his scandalous hammering of seemingly barbarous rhythms. Saint-Saëns was no “Neo”-classicist: he had lived the period when Mendelssohn’s Romanticism could still be suffused with the remnants of the “real”, lived Classical tradition.

Saint-Saëns had begun composing at an age when most children are unable to read or write, let alone play an instrument or creating anything innovative. His first work for violin and piano dates from 1841, when the composer was not yet five; just six months later, he wrote his first Sonata for violin and piano, a complete work in three movements, dedicated to Antoine Bessems (1806-1868), a famous Belgian violinist with whom he tried it out. This Sonata, though first in Saint-Saëns’ compositional output, did not receive the official title of “Violin Sonata no. 1”; it has been recently published but had remained in the manuscript form for nearly two centuries.

The name of “Violin Sonata no. 1” is deservedly attributed, instead, to a much later work by the French composer, recorded here together with the Second Sonata and the Triptych op. 136.

Sonata no. 1 was completed by Saint-Saëns in 1885. It is dedicated to Martin Marsick, the founder of the eponymous string quartet, with which Saint-Saëns had often played (to name but one occasion, in 1879 the Marsick Quartet and Saint-Saëns premiered César Franck’s magnificent Piano Quintet. Saint-Saëns had toured Switzerland with Marsick the year before writing this Sonata for him). Saint-Saëns had become particularly attracted by chamber music at a relatively mature age, having focused on symphonic music at an earlier stage of his compositional activity. However, he had become a zealous apostle of chamber music, co-founding with Romain Bussine, in 1871, the Société Nationale de Musique for the dissemination of French music, and most notably of chamber music.

This Sonata is in the traditional form, made of four movements; however, these four movements are coupled in pairs, to be played without intermission except that after the Adagio. This particular compositional solution was going to be employed again by Saint-Saëns in 1886, in his celebrated “Organ” Symphony.

This Sonata is less frequently played than it deserves, possibly also due to its sheer technical difficulty and musical demands; yet, these very reasons should advocate a more widespread inclusion of this splendid work in concert programmes. Virtuosity is a key element of this piece, as of many other works by Saint-Saëns, who was a very brilliant pianist and organist himself and was used to know the finest details of the performing techniques of all orchestral instruments.

The opening theme of the first movement is built on musical waves, in a thick texture interwoven with references to motifs and structural elements which will resurface throughout the Sonata. By way of contrast, the second theme is much lighter and transparent, with multicoloured refractions. Microstructural elements are in a constant interplay between the two instruments, and Saint-Saëns’ masterly handling of the compositional material is evident. His skill in the treatment of the Sonata form is amply demonstrated by the development, whereby contrapuntal techniques are abundantly employed. This doubtlessly came to Saint-Saëns from his longtime acquaintance with Baroque music (especially Bach) and organ writing.

The second movement, Adagio, which follows the first seamlessly, is dreamy and full of lyricism. The chosen form is one of the most typical for slow movements, i.e. the Lied form (ABA), with a central section marked by a powerful inspiration, in opposition to the poetic nuances of the outer parts.

After the only break in this Sonata, a gentle Scherzo, paced as an Allegretto, opens the second half of the composition. It is a rather Mendelssohnian Scherzo, with elven suggestions and transparent sounds. The enchanted atmosphere of the Scherzo, with its fantastic dimension, fades into a mystical and grave Chorale, which works as a bridge between the fairy-tale sounds of the Scherzo and the thrilling finale. Here virtuosity comes to the fore in a preponderant fashion; it is similar to a wild run, a perpetuum mobile, a whirlwind of unceasingly intermingling colours. The two instruments change places frequently, as if in a breathless chase, one performing the enthralling sequences of notes, the other punctuating them with discrete accompaniments, leading to an intoxicating close.

It has been suggested that this Sonata – or perhaps Franck’s? – might have been the hidden model for “Vinteuil’s Sonata”, the fictional musical work which is at the core of Proust’s Swann’s Way and symbolizes Mr Swann’s love for Odette. True, Proust provides the reader with a detailed description of “Vinteuil’s Sonata”, and this does not correspond to the structure of Saint-Saëns’ work; however, one of the main features of the imaginary musical piece in Proust’s text is the recurring “little phrase”, which in fact “returns” both in the literary work and in Saint-Saëns’ composition.

The First Sonata, with its utter virtuosity, clearly embodies the heroic, Romantic vocation of its composer, and the influence of such composers/performers as Franz Liszt. By way of contrast, the Second Sonata is deeply pervaded by a Neoclassical mood, with a much greater sobriety, balance, and aplomb.

The very circumstances of this Sonata’s premiere reveal something about Saint-Saëns’ exceptionally long career and how it impacted on his style, and on the reception of that style by his contemporaries. The Sonata, in fact, was premiered by Saint-Saëns himself at the piano, together with Pablo de Sarasate, the great violinist-cum-composer who had been his chamber music partner for more than three decades. The occasion for that performance was a concert at the Salle Pleyel, celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of Saint-Saëns’ first public performance (1846-1896). In that concert, the composer also premiered his Fifth Piano Concerto. A month earlier, the piece had been privately performed by two other superb artists, Eugène Ysaÿe and Raoul Pugno. The occasion of that jubilee concert was so important for Saint-Saëns that he actually “stole” the privilege of premiering the chamber music work from those who should normally have claimed rights on the premiere, i.e. the dedicatees. The Sonata had been dedicated to Léon-Alexandre Carembat and to his wife, Marie-Louise Adolphi; he was a violinist performing at the Opéra, she was a pianist, and both had been awarded a Premier Prix for their respective instruments at the Conservatoire.

The reasons for that dedication had been given by Saint-Saëns to the publisher, Durand, in the following terms: the couple had often played his chamber music works, “without letting me know in any way, whereas so many others, whenever they play anything by me, even at the end of the world, quickly send me the program with a view to laying claims to my gratitude. That did deserve a reward, I promised to do something for them, and I have kept my promise”.

This Sonata, too, is in four movements; the first is in the Sonata form, with the usual, pronounced opposition between the two themes. The first is driven by an intense emotional power, with plenty of energy; the second is much sweeter and more subdued. A curious compositional trait is that the “reconciliation” of the two themes in the recapitulation is complete: they are played together, instead of one after the other.

In this case, the Scherzo is found as the second movement, and it features a remarkable three-part canon which showcases Saint-Saëns’ extraordinary compositional ability. With a touch of pride, the composer wrote to the publisher: “I don’t think that Franck, whose canons are all praised, ever composed one as pretty as the one that forms the Trio of this scherzo, a canon that I wrote in Aswan”. In fact, the entire Sonata was written during a journey in Egypt, and it displays traits of exoticism. These are particularly evident in the slow (comparatively slow) movement, the third (Andante), where influences from Debussy can be observed, in the presence of harmonic ambiguity. This is remarkable since Saint-Saëns openly disliked Impressionism, but perhaps was not as impermeable to its suggestions as he would have loved to be. The fourth movement, in the Rondo form, is pure Saint-Saëns with an abundant presence of sense of humour and a truly Neoclassical inspiration.

Exoticism had found its way in the Second Sonata, and was abundantly present also in the Fifth Piano Concerto premiered with it (the so-called “Egyptian Concerto”). It pervades even more clearly the Triptych closing this programme. Dedicated to Elisabeth, Queen of the Belgians (but of Austrian descent), it was written in 1912. Belgium had Congo among its colonies, and the second movement of the Triptyque has in fact the title of “Vision congolaise”. The outer movements are also markedly exotic and profoundly original, showcasing the composer’s unrelenting and brilliant musical imagination, which inspired his first works for violin and piano as a child as well as those written in a very mature age.

Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2023 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads