Tracklist: VIDEO

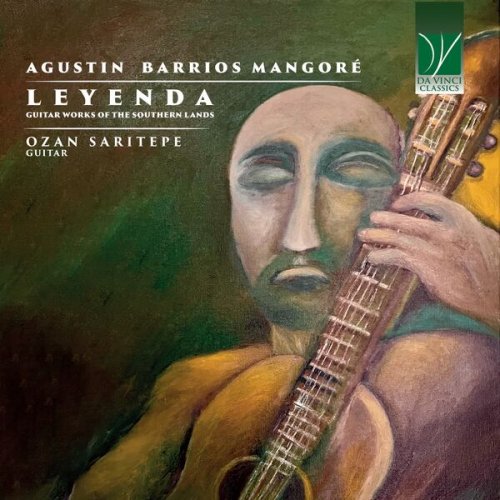

The figure of Agustín Pío Barrios, who at a later time would add “Mangoré” to his family name, is fascinating, original, unique and impossible to frame within the usual schemes of the Western musical tradition. One of the greatest guitarists and composers of the early twentieth century, his biography differs under many viewpoints from that of most of his Western colleagues. In spite of this, or possibly precisely for this reason, he is regarded today as a true lighthouse in the ocean of guitar music.

He was born on May 23rd, 1885, in San Juan Bautista de las Misiones, a small town in Paraguay. His identity and his music, as well as his public persona, would always be bound to his Paraguayan roots, and it can safely be asserted that he was the first great Paraguayan musician to obtain international renown.