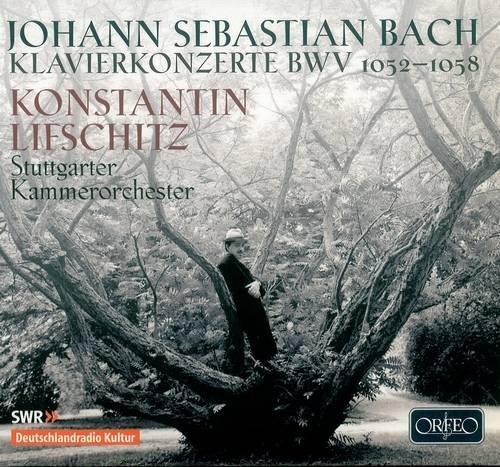

Konstantin Lifshitz - J.S. Bach: Piano Concertos BWV 1052-1058 (2011) CD-Rip

BAND/ARTIST: Konstantin Lifshitz

- Title: J.S. Bach: Piano Concertos BWV 1052-1058

- Year Of Release: 2011

- Label: Orfeo

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

- Total Time: 01:48:29

- Total Size: 571 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

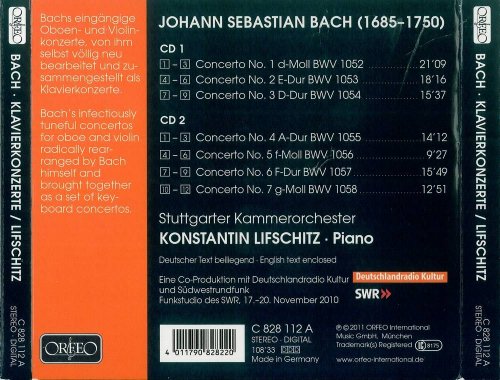

Tracklist:

CD 1:

Concerto No.1 BWV 1052

1. I. Allegro

2. II. Adagio

3. III. Allegro

Concerto No.2 BWV 1053

4. I

5. II. Siciliano

6. III. Allegro

Concerto No.3 BWV 1054

7. I

8. II. Adagio e piano sempre

9. III. Allegro

CD 2:

Concerto No.4 BWV 1055

01. I. Allegro

02. II. Larghetto

03. III. Allegro ma non tanto

Concerto No.5 BWV 1056

04. I

05. II. Largo

06. III. Presto

Concerto No.6 BWV 1057

07. I

08. II. Andante

09. III. Allegro assai

Concerto No.7 BWV 1058

10. I

11. II. Andante

12. III. Allegro assai

Performers:

Konstantin Lifshitz, piano

Stuttgarter Kammerorchester

CD 1:

Concerto No.1 BWV 1052

1. I. Allegro

2. II. Adagio

3. III. Allegro

Concerto No.2 BWV 1053

4. I

5. II. Siciliano

6. III. Allegro

Concerto No.3 BWV 1054

7. I

8. II. Adagio e piano sempre

9. III. Allegro

CD 2:

Concerto No.4 BWV 1055

01. I. Allegro

02. II. Larghetto

03. III. Allegro ma non tanto

Concerto No.5 BWV 1056

04. I

05. II. Largo

06. III. Presto

Concerto No.6 BWV 1057

07. I

08. II. Andante

09. III. Allegro assai

Concerto No.7 BWV 1058

10. I

11. II. Andante

12. III. Allegro assai

Performers:

Konstantin Lifshitz, piano

Stuttgarter Kammerorchester

Well, well! We have a winner in the Bach Keyboard Concerto CD contest, and it is Konstantin Lifschitz, winner of a Grammy in 1996 for his recording of the Goldberg Variations. And what is it, exactly, that places Lifschitz head and shoulders above his competition? It is the style he employs, difficult to put into words but immediately discernible to the ear, wherein he plays these works (along with the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra) in a manner that is more curved than linear, more flowing than staccato, with innumerable details of shading, coloring, and yes, even additional little musical fillips. I had to hit the Back button on my CD player a few times while listening to his recording of BWV 1052 because I couldn’t believe my ears. Lifschitz adds a few little turns (you might, untechnically, call them half-trills) and, at one point, actually plays a left-hand figuration in a completely different rhythmic stress from the right. This is Bach pianism at the highest level of art and technique, and it is to Lifschitz’s credit that he manages all of this within a pure, continent style.

As I say, in the hands of this pianist and orchestra the music is “curved.” By this I mean that it flows like water, in a consistent legato stream that lifts the notes off the page. Anyone who has ever seen even one page of an original Bach manuscript (one such is reproduced here, on the inside back cover of the fold-out cardboard packaging) will know what I mean. The way Bach drew the connecting lines of his 16th and 32nd notes, for that matter the notes and stems themselves, was curved—sometimes almost a curlicue—and not ruler-edged straight. I have always taken this as an indication of the way he wanted his music played and sung. I firmly believe that Wilhelm Furtwängler was right when he said that Bach was not the end of the Baroque composers but the first Romantic. It’s all there in the music, if you have the wit to hear it. Anyone who plays the famous Air on the G String in a manner other than legato, and sensuous legato at that, has no understanding of what they’re playing, and to my ears, what goes for the Air on the G String goes for the slow movements of his concertos. Then, if you are to play the Andante and Adagio movements of his concertos as you would play the Air , you must of necessity play the outer movements in a similar manner. QED. In their capable hands, the music not only has sparkle and momentum, but also gravitas. One of the highest compliments I can pay to Lifschitz is that his performance of the Concerto in D Minor reminded me of a performance I once heard played by George Shearing.

The purists may still throw their hands up in frustration, since Lifschitz uses the cadenza in the last movement of the first concerto that was written by Johannes Brahms … and, of course, he’s also using a modern piano, the Philistine! But, of course, the Coming of St. Glenn Gould has permanently influenced our Bach listening. Thanks to Gould, it’s OK to use a modern piano in Bach as long as you play in a crisp manner with little or no pedal, even when the accompanying orchestra, as here, is using recorders and straight tone in the strings. It’s curious that although Michael Hofstetter is credited as the orchestra’s current music director and conductor, his name does not appear in the credits for this album. Thus I would assume that they are either playing without a conductor, or Lifschitz is conducting from the keyboard. In either case, they follow the pianist’s lead with both exact musical precision and exactly the same feeling for the music, note for note and phrase for phrase.

This is a recording to take its place alongside the sonatas and partitas for solo violin as played by Sigiswald Kuijken, Benjamin Britten’s classic account of the Brandenburg Concertos, Helmuth Rilling’s recording of the St. Matthew Passion , Wanda Landowska’s Italian Concerto, and Monica Huggett’s recent version of the St. John Passion as being among the most treasurable Bach recordings ever issued. This one is a must. -- Lynn René Bayley

As I say, in the hands of this pianist and orchestra the music is “curved.” By this I mean that it flows like water, in a consistent legato stream that lifts the notes off the page. Anyone who has ever seen even one page of an original Bach manuscript (one such is reproduced here, on the inside back cover of the fold-out cardboard packaging) will know what I mean. The way Bach drew the connecting lines of his 16th and 32nd notes, for that matter the notes and stems themselves, was curved—sometimes almost a curlicue—and not ruler-edged straight. I have always taken this as an indication of the way he wanted his music played and sung. I firmly believe that Wilhelm Furtwängler was right when he said that Bach was not the end of the Baroque composers but the first Romantic. It’s all there in the music, if you have the wit to hear it. Anyone who plays the famous Air on the G String in a manner other than legato, and sensuous legato at that, has no understanding of what they’re playing, and to my ears, what goes for the Air on the G String goes for the slow movements of his concertos. Then, if you are to play the Andante and Adagio movements of his concertos as you would play the Air , you must of necessity play the outer movements in a similar manner. QED. In their capable hands, the music not only has sparkle and momentum, but also gravitas. One of the highest compliments I can pay to Lifschitz is that his performance of the Concerto in D Minor reminded me of a performance I once heard played by George Shearing.

The purists may still throw their hands up in frustration, since Lifschitz uses the cadenza in the last movement of the first concerto that was written by Johannes Brahms … and, of course, he’s also using a modern piano, the Philistine! But, of course, the Coming of St. Glenn Gould has permanently influenced our Bach listening. Thanks to Gould, it’s OK to use a modern piano in Bach as long as you play in a crisp manner with little or no pedal, even when the accompanying orchestra, as here, is using recorders and straight tone in the strings. It’s curious that although Michael Hofstetter is credited as the orchestra’s current music director and conductor, his name does not appear in the credits for this album. Thus I would assume that they are either playing without a conductor, or Lifschitz is conducting from the keyboard. In either case, they follow the pianist’s lead with both exact musical precision and exactly the same feeling for the music, note for note and phrase for phrase.

This is a recording to take its place alongside the sonatas and partitas for solo violin as played by Sigiswald Kuijken, Benjamin Britten’s classic account of the Brandenburg Concertos, Helmuth Rilling’s recording of the St. Matthew Passion , Wanda Landowska’s Italian Concerto, and Monica Huggett’s recent version of the St. John Passion as being among the most treasurable Bach recordings ever issued. This one is a must. -- Lynn René Bayley

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads