The question of language has become one of primary importance in contemporary music, at least since the early 1900s. Prior to that period, each musician did have his or her own musical “dialect”, i.e. a particular stylistic mark determined by his or her personality, education etc.; but, at the same time, there was a single musical “language”, which was “spoken” throughout the Western countries.

Then came the great tragedies of the twentieth century, and Adorno’s claim that to write poetry (and, by extension, to write “poetic” music) was “barbaric” after Auschwitz. And the explorations of the avant-gardes, which favoured effects or elegant design over communication. Music as a language presupposes somebody who “speaks” and somebody who “listens”: their communication is made possible by their sharing of a common language. When music refuses to abide by what has been handed down by tradition, then every musician must carve his or her own language, with the clear risk (most often actualized) that nobody else will understand it. This is possibly a primary cause for the generalized disaffection of many people who used to be concertgoers, and who perhaps still attend traditional concert seasons, but who cannot stand the experimentalism of the late-twentieth century Avant-gardes. This is not meant, of course, as a critique of the Avant-gardes or an oversimplification of much more complex processes. It is merely the attempt to point out, all too concisely, that every composer nowadays must take an explicit stance as regards his or her tradition, their position with respect to it, the degree to which one should adhere to it. Whereas in the second half of the twentieth century the mere thought of tonality, or something akin to it, was considered as heretical in the circles of “serious” modern composers, after 2000 there have been some attempts to rediscover a language in which most of the greatest masterpieces of Western music had been written and which, arguably, had far from exhausted its potential. It is not a matter of naivety, as if ignoring what happened between 1900 and 2000; rather, it is the self-conscious assumption of an approach which does not despise twentieth-century music, but also offers new perspectives for that of the twenty-first century. Still, this itinerary in search of one’s true musical personality is far from easy, far from straightforward, and normally causes more suffering that it relieves – at least, to the composer. By listening to this album with chamber music works composed in the last 4-5 years, one is impressed by the continuing quest which seems to manifest itself in the various pieces recorded here. It is a quest involving virtually all dimensions of musical playing and composing – rhythm, pitch and its organization, timbre, harmony etc.; the composer is evidently in search of answers, be they exquisitely musical or even existential ones. Frequently, this quest is manifested and displayed even in the actual musical gestures played by the instruments. It is not just a “background” quest, in which the composer laboriously found his own voice by selecting those elements of tradition he felt at home with. It is also a quest which becomes transparent in the uncertain and wavering steps of the instruments. At the same time, this kind of quest is not perceived as a frailty of the musical work, or as a weakness; rather, the narrative evoked by each piece finds its optimal expression precisely in the careful balance of what has already been said (and therefore is understandable, even musically), and what is, and should be, a novelty and something specific, original, unique for the composer. Within this album, references to the glorious Western tradition abound; and even though not all of them may have been intended as explicit citations or homages, still they build a net of acoustic and spiritual references which concur in the definition of Bernabò’s unique and special language. In these pieces, one can easily find allusions to great composers of the past; yet, and even though some of them may be more evident than others, still the result is the conscious or unconscious establishment of the boundaries of a creativity which deeply needs them. Our society, which prizes freedom and liberty above all other values, is convinced that limits and boundaries are always pernicious. However, when led to discover the impossibility of endless possibilities, many will choose some kind of boundary, which is absolutely necessary if one wants truly to create art.

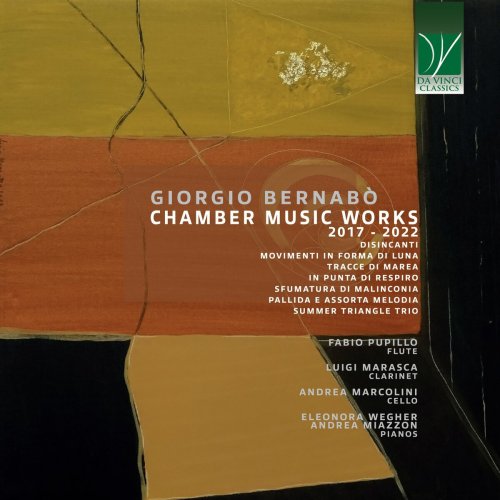

Thus, one element which constantly resurfaces in this album is Bernabò’s fecund relationship with polyphony. It is an exquisitely instrumental polyphony, in which even the wind’s parts are led to clusters of notes or to produce sounds which the listener may perceive as animated by an articulation into more than one polyphonic melody. Of this continuing tension – the tension of quest, the tension of polyphony where parts intertwine and play with each other until a pattern appears, the tension toward language – Bernabo’s music breathes and lives. Even when it depicts stability or stillness, inertia or calm, it is provided with an inner soul which channels this tension toward contemplation, and contemplation toward a sudden intuition. This tension is also embodied, musically, by the abundant use of the interval of second. This is perhaps one of the most distinguished and distinguishable traits of Bernabò’s style: i.e., his abundant use of the interval of second, the most dissonant of all musical intervals, and the one which unavoidably brings within itself the promise of a restauration. Another fil rouge connecting the pieces recorded here is that of extramusical inspiration. Far from becoming a mere illustration of concept or artworks which are extraneous to music, music engages in a tight dialogue of beauty and mutual self-understanding with literature and visual art. Each composition is the result of “suggestions” intended as creative ideas and stimuli for the genesis of the works. Most of the pieces are the result of pictorial or literary stimuli. Disincanti (“Disenchantments”), for instance, were created under the influence of the poetry of Giacomo Leopardi. One of the greatest Italian Romantic poets, Leopardi – who died at a young age like so many of his peers – developed a very tragical and dark view of human life and of its meaning. Still, in spite of its deep sadness – or precisely thanks to it – Leopardi’s poetry invariably seduces its readers, be they adolescents who face it for the first time at school or adults who repeatedly come, again and again, to Leopardi’s voice. In these pieces, rhythm and polyphony intertwine tightly with each other, and even the individual lines of polyphony reveal themselves as constituting more than one single line. Even the melodies can be broken – while maintaining a unity of their own – and be perceived, at one and the same time, as “one” and as “many”. Bernabò’s quest for a harmonic/melodic itinerary is particularly evident in the second Disincanto, whose unending search for meaning seems to represent a symbol or an icon for Leopardi’s aspiration toward infinity. Just as Leopardi was never content with the materiality of things of this world, so does music unceasingly seek an exquisitely tonal, but also intensely modern path. As Bernabò affirms, these pieces were created by attempting to move within that magical boundary between reality and dream. When faced with reality, our dreams seem to dissolve (as Leopardi memorably affirms in A Silvia); however, for the composer, it is precisely at that moment that the artist can find the possibility of grasping a shed of dream, and of believing in something. Leopardi also wrote a memorable Ode to the Moon (Canto di un pastore errante), which interrogates the Moon as to her meaning in heaven. And this tendency to lift the gaze up to heaven, where the miracle of infinity takes place inspired Movimenti in forma di luna (“Movements in the shape of the moon”). These pieces had been originally composed for oboe and piano; however, after listening to their premiere when they had had to be played with the clarinet, the composer acknowledged that the clarinet’s sound was better suited for their performance. The titles assigned to the various movements were attributed on the basis of what had appeared in the composer’s life by observing the moon from the woods by which his home is found. Contemplating the moon seems to be a very Romantic, and decidedly naïve act; yet, one of the underlying principles is that what catches the heart is probably what will remain successful on more than one occasion. The premiere of these pieces included the participation of a female dancer, pointing out the dance-style of these short miniatures. In these pieces, we find an alternation of melos, as the nearly-improvised wanderings of the clarinet’s melody, but also pointillism, a free and dreamy Preludizing, but also an explicit quest for a horizon and a meaning. The cycle closes with a Straussian scherzando, with surprising melodic/harmonic itineraries. Tracce di marea and In punta di respiro were created following the impression of a painting exhibition. Observing some paintings, some lines, some small details prompted the composer to go back to experiences he had lived when residing in Liguria. For instance, Tracce di marea is not the description, but rather the reappropriation of some feelings the composer had lived in Liguria, after sea storms. The third piece, more recent than the others, refers instead to poetry, and in particular to Ungaretti’s memorable Malinconia (from “L’allegria”). The feelings evoked by that text caused the reading of this literary work to become the propelling force for the composition of Sfumatura di malinconia. It represents the fascination we find ourselves in when we stay on the border between life and death, and where existential questions become pressing. Another poet, Eugenio Montale, and another literary work, Meriggiare pallido e assorto, inspired Pallida e assorta melodia. The poetry’s powerful evocation of an afternoon where nothing at all happens – and the existential void behind this feeling – is musically translated by an ostinato of B-flat at the piano’s right hand. This lends a feeling of fixity, of inexorability, but also of a wish to free oneself from that obsession. In these pieces, the aural space of the keyboard is explored, while the cello’s warm and deep voice suggests an instrumental transposition of the need for breathing we have. The starry heaven is the protagonist also of the three pieces constituting the Summer Triangle: pieces commissioned by a Trio called after a star, Vega. This encouraged the “involvement” of the other stars of the summer heaven. The second piece is the expressive heart of the cycle, with its impalpable, evanescent sounds.

Together, these pieces provide us with a satisfactory and well-considered experience of what music has been and can still become, in a fruitful dialogue with the past but also in a radical opening to the future.

Chiara Bertoglio