“Pearls are tears”, as the old adage goes, repeated perhaps too often by husbands who are unwilling to buy expensive pearl necklaces to their wives. In the case of this album, one should rather say that tears are pearls. None of the pieces recorded here reaches the length of five minutes: they are all miniatures, perfect and finished in themselves just as the small spheres born of an oyster’s tears. They represent the quintessentially Romantic form and genre of the musical aphorism. Romantic aesthetics delighted in the creation of minor masterpieces, just as it craved the increasingly long symphonies or symphonic poems.

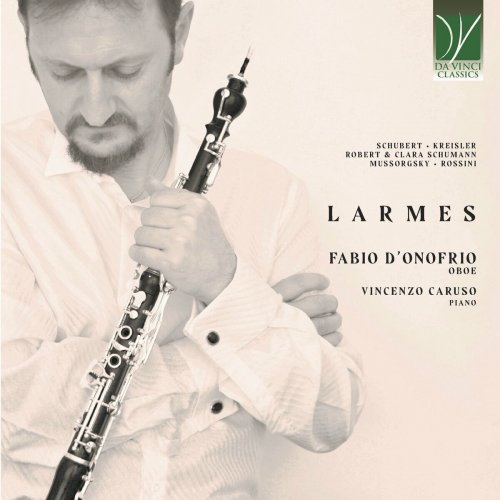

A few of the pieces recorded here were conceived purposefully for the oboe, but all, including these, are tightly bound to the great tradition of the German Lied. As Fabio D’Onofrio explains, it is through his acquaintance with period instruments that he understood profoundly the mystery of the human voice and how it dovetails with instrumental music. The particular timbre, sound, and tone of period instruments have the power to elicit, in the player, the awareness about his or her musicality: the musicality of their bodies, which, when singing, become musical instruments in turn. Thus, D’Onofrio created this album with the purpose of letting this deeply human singing emerge; through singing, both the instrument and its technique are transcended, even though they remain the insuppressible medium for this singing to blossom. D’Onofrio’s elective partner, in this recording, is a Viennese Oboe lent to him by Sebastian Frese, of the Viennese Oboe Association, and a colleague playing in the Wiener Akademie Orchester. The mellow, cantabile tone of this instrument, built by Austrian craftsman Hermann Zuleger in the early decades of the twentieth century, became the instrumental transfiguration of the performer’s, and of the composers’, inner voice.

Artsongs derived their raison d’être from the close relationship between the poetic word and music; typically, Lieder texts were short and concise, and, when they were not, composers used to set them to music strophically. In this way, it was possible to sing as many (or as little) stanzas as one wished. Consequently, the Lied’s structure had to be compact, chiseled, without concessions to grandiloquence or to the unnecessary. It was an almost ascetic exercise, whereby the strict adherence of music and word determined a seeming subservience of music to the word; but, at the same time, this discipline also freed music from all superfluity, especially in the hands of the Romantic geniuses.

This is certainly true of Franz Schubert, the undisputed master of this genre, who left unforgettable Lieder dating back from his early adolescence and until his very last year. Indeed, Gute Nacht, the opening piece of Winterreise, belongs in that “late” period of Schubert’s life, which can be defined as “late” only because it preceded his untimely death by a few months – not because its composer was “aged”. Winterreise, the greatest Lied cycle written by Schubert, opens with the despised lover’s desolate decision to leave his beloved’s home. From the warmth of a house and of a family, he ventures into the icy winter, which will transform his feelings and personality and abandon him to that Sehnsucht, that deep nostalgia-cum-desire, which characterizes the Romantic aesthetics so powerfully. The other Lieder by Schubert recorded here include one of the most famous of all, Ständchen, but also one which represents the composer’s worldview perfectly, i.e. Nacht und Träume. Dreams were particularly important for Schubert, whose literary output includes a lengthy, and pre-psychoanalytical, description of one of his most significant dreams. Psychoanalytically, dreams and water are also deeply related; thus, Auf dem Wasser zu singen, with its glittering waters and shining waves, is yet another declination of the theme of night and of the unconscious.

Schubert “taught” Schumann, in a manner of speaking: although the two never met in person, Schumann admired Schubert deeply, and drew from his music numerous important lessons for his own compositional activity. Schumann’s three Romanzen op. 94 were written in 1849, as a Christmas present for his beloved wife Clara; these short, intimate, unpretentious but deeply intense pieces speak volumes about the oboe’s capability to replace the human voice and even to hint to an unsaid, unwritten and untold text. Their family life was happy, insofar as the two were deeply and faithfully in love with each other and had a joyfully noisy bunch of children; but tears certainly were not missing, from the time preceding their wedding (against which Clara’s father opposed a legal battle) until Robert’s last years with a troubling mental condition.

Still, the tenderness of their love is beautifully expressed by the minuscule, but extremely famous and sweet Widmung, which encapsulates the transparent beauty of their relationship. Dreams, such as those narrated by Schubert in his Lied, are also protagonists of Der Nussbaum, depicting a walnut tree and its fluent foliage, under which, in a rural setting, a girl is letting her fantasy wander and her thoughts fly.

Clara was not only one of the greatest pianists of the century, but also one of the major female composers. Different from other female musicians, she was actively encouraged in her creative activity by her husband, even though she always felt inferior to him. Certainly, having a genius of Schumann’s calibre living under the same roof is not likely to increase a composer’s self-esteem; and, in fact, she did not venture in the large-scale works (symphonies, oratorios) which she could easily have attempted. Though she did write long (and beautiful) works, her talent was at ease particularly in the short forms, such as her touching Lieder op. 13 recorded here. Her love songs, interwoven with enchanted depictions of nature – seen with a typically Romantic gaze, where enchantment, awe, joy and wonder dovetail – lead us to the contemplation of a lotus flower. Its beauty is surrounded by the blueness of a lake lit by the moon, whose golden rays make the water glisten. Clara Schumann’s use of the suspended chord is almost like a gate to infiniteness, to the mystery of the Unending.

The remaining three pieces are as different as they could be: there is the lightness of Kreisler’s Vienna, a city where situations can be “desperate but not serious”, and Love’s Lost Labours are depicted in the form of a charming and nonchalant Waltz. Then there is the seriousness of the prince of opera buffa, Rossini; someone whom it was difficult to take seriously, but who struggled with a deep depression which neither his contemporaries nor his posterity accepted. Speaking to his friend Max Maria von Weber (who was the son of the late composer Carl Maria), Rossini admitted that writing music was still a necessity, a need for him. And this happened at a time (1865) when he had said farewell to the composition of operas, and had left the stage for good with his last serious opera, Guglielmo Tell. This piece was written to pay homage to the memory of a friend of Rossini, who had been a virtuoso cellist, i.e. Michail Vielgorsky; its autograph is found in St. Petersburg and is dated November 18th, 1858. The “tear” shed by Rossini is beautified by his music; its touching and authentic character (so different from the comic and spectacular elements of Rossini’s buffo operas!) is telling about the composer’s innermost soul and his capacity to mourn those he had loved in an intimate, tender fashion. This piece, with its elegiac theme, is heartfelt, and draws from the composer’s deepest memories a profound inspiration.

Finally, there is the passionate Russian soul of Mussorgsky, whose bulky and bearded figure seems the least likely to shed tears – but who was certainly able to weep, to mourn, and to express the most delicate sentiments through his music. Mussorgsky’s Une Larme was actually the stimulus prompting the creation of this entire album. His piece by this title, written in 1880, is his last creation for the piano; it narrates the condition of loneliness, isolation, even of despair which had grasped the composer, whose health was undermined by his alcoholism, and whose friends had abandoned him. Yet, with his Une Larme he managed to transform his deep grief into beauty.

So, yes, tears are pearls indeed.

Chiara Bertoglio