Leila Schayegh, Vaclav Luks, Felix Knec - Franz Benda: Violin Sonatas (2012) CD-Rip

BAND/ARTIST: Leila Schayegh, Vaclav Luks, Felix Knec

- Title: Franz Benda: Violin Sonatas

- Year Of Release: 2012

- Label: Glossa

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: APE (image+.cue,log,scans)

- Total Time: 67:15

- Total Size: 430 Mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

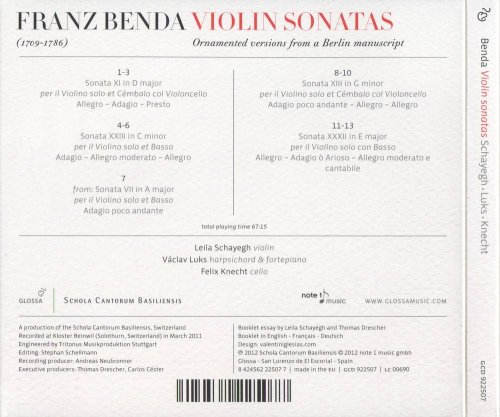

Tracklist:

Sonata XI in D major (Lee III-25)

"per il Violino solo et Cembalo col Violoncello"

1. Allegro

2. Adagio

3. Presto

ВС: harpsichord & violoncello

Sonata XXIII in C minor (Lee III-9)

"per il Violino solo et Basso"

4. Adagio

5. Allegro moderato

6. Allegro

вс: fortepiano

from: Sonata VII in A major (Lee III-103)

"per il Violino solo et Basso"

7. Adagio poco andante

ВС: harpsichord & violoncello

Sonata XIII in G minor (Lee III-89)

"per il Violino solo et Cembalo col Violoncello"

8. Adagio poco andante

9. Allegro

10. Allegro

ВС: harpsichord & violoncello

Sonata XXXII in E major (Lee III-50)

"per il Violino solo con Basso"

11. Allegro

12. Adagio ò Arioso

13. Allegro moderato e cantabile

вс: fortepiano & violoncello

Performers:

Leila Schayegh

violin (Andrea Guarneri, Cremona, 1675)

Vaclav Luks

harpsichord (Martin Skowroneck, 1987, after Michael Mietke)

fortepiano (Denzil Wraight, 2005, after Bartolomeo Cristofori, 1726)

Felix Knecht

violoncello (workshop of Carlo Antonio Testore, Milano, 1727)

Sonata XI in D major (Lee III-25)

"per il Violino solo et Cembalo col Violoncello"

1. Allegro

2. Adagio

3. Presto

ВС: harpsichord & violoncello

Sonata XXIII in C minor (Lee III-9)

"per il Violino solo et Basso"

4. Adagio

5. Allegro moderato

6. Allegro

вс: fortepiano

from: Sonata VII in A major (Lee III-103)

"per il Violino solo et Basso"

7. Adagio poco andante

ВС: harpsichord & violoncello

Sonata XIII in G minor (Lee III-89)

"per il Violino solo et Cembalo col Violoncello"

8. Adagio poco andante

9. Allegro

10. Allegro

ВС: harpsichord & violoncello

Sonata XXXII in E major (Lee III-50)

"per il Violino solo con Basso"

11. Allegro

12. Adagio ò Arioso

13. Allegro moderato e cantabile

вс: fortepiano & violoncello

Performers:

Leila Schayegh

violin (Andrea Guarneri, Cremona, 1675)

Vaclav Luks

harpsichord (Martin Skowroneck, 1987, after Michael Mietke)

fortepiano (Denzil Wraight, 2005, after Bartolomeo Cristofori, 1726)

Felix Knecht

violoncello (workshop of Carlo Antonio Testore, Milano, 1727)

Leila Schayegh, Václav Luks, and Felix Knecht present four of Franz Benda’s violin sonatas (and a movement extracted from another sonata) from a collection of 34 ornamented examples of the genre included in manuscript form among the holdings of the Berlin State Library. The ornamentation, provided for both the slow movements, for which Benda earned a reputation, as well as for faster ones, could serve as a sort of compendium of German period practice (Schayegh’s own notes suggest that the works hail from about 1760). The first sonata in the program, No. 11 in the manuscript, sounds Haydnesque (although Charles Burney deemed that among the Berlin composers, only Benda and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach had truly developed styles of their own) in its melodic design; the ornamentation flies thick and fast from the outset of its first-movement Allegro. The ensemble accompanies the solo violin in several different ways throughout the program, in the 11th Sonata enlisting harpsichord and cello; the harpsichord here provides a bright underlay for violinistic encrustations of ornamentation. Schayegh produces a transparent timbral lightness from her 1675 Andrea Guarneri, which matches the harpsichord’s jewel-like sonority. The slow movement (with its own brief cadenza near the end) serves as the first example of the kind of melodic writing for which Benda achieved a reputation in his own day (he had worked as a singer before he became a violinist). Like Giuseppe Tartini, he apparently valued the instrument’s melodic capabilities, though Benda’s sonatas demand great facility from the violinist in addition to a keen sense of their lyrical possibilities. The ensemble sounds brisk but songlike in the Presto finale.

In the second sonata, No. 23, the fortepiano assumes the solo responsibility for the continuo part ( basso in the title). This work follows the pattern familiar from works by Tartini (and even Giovanni Battista Somis), of a moderately paced movement followed by one a bit faster and capped off by an even quicker one. Luks’s fortepiano, a modern instrument made after a 1726 instrument made by Bartolomeo Cristofori, matches Schayegh’s sonorities, though she displays a tonal richness in the lower registers that hardly found expression in Sonata No. 11.

Harpsichord and cello return in the slow movement (Adagio poco andante, which also features a cadenza at the end) from the Seventh Sonata, its poignant sensibility bleeding through the figuration surrounding the main melody. The same instrumentation composes the continuo grouping for the 13th Sonata, also cast in three movements (the first, slow, the second two, fast and faster). Schayegh’s notes suggest that while the heaviest encrustations of ornaments appear in slow movements, the fast ones display a wide variety of procedures of varying the material, and that may account for the greater simplicity of movements like this sonata’s final Allegro.

Sonata No. 32 opens with an Allegro that struts breathtakingly in double-stops but also features bursts of ornamentation, pyrotechnical display in Schayegh’s reading. The choice of fortepiano as the continuo instrument highlights the movement’s bounce. The slow movement throws a double punch near the end, with a buildup of figuration leading to a cadenza. The finale relies on melodic appeal rather than virtuosic bravado.

Schayegh’s tone, not always mellifluous, sounds a great deal different from the tart wheezing that earlier period practitioners might have produced, and Glossa’s engineers have captured it vividly, though the clarity they’ve brought to the recorded sound represents all the instruments in sharp focus. Schayegh’s program overlaps in only one Sonata (No. 23 in C Minor) the collection made by violinist Hans-Joachim Berg and harpsichord player Naoko Akutagawa on Naxos 8.572307 (also featuring period ornamentation, Fanfare 35:4). While I recommended their performances, listeners may find a warmer graciousness in Schayegh’s readings; the engineers for both make the violins sound somewhat abrasive. In reviewing violinist Anton Steck’s readings of six of Benda’s sonatas (none of which overlap with Schayegh’s program) with Christian Rieger, on CPO 777 214, Fanfare 32:1, I noted that Steck and Rieger’s instruments “produce consistently ingratiating textures, though there can be no mistaking Steck’s violin for a modern one.” And though he may be playing from an older edition, there’s no resisting his exuberant sparkle in the second movement of the opening Sonata in C Major. In that same review, I disparaged the textures produced by Ivan Zenatý and his ensemble (Pwre Hejnýy, cello, and Jaroslav T?ma, harpsichord, on Arta 1022-2111, which I reviewed in Fanfare 18:6. Zenatý plays with a great gusto, but many will feel that whatever he can do will necessarily fall short of the effect of the original ornaments. For those interested in exploring Benda’s work, in this native environment, Schayegh’s collection should provide a heady enough brew as an introduction, and because of the lack of significant overlap, should stand alongside Berg’s collection, their differences complementing each other in creating a richer understanding of the composer’s aim of creating a sweetly melodic repast, richly glazed. Highly recommended. -- Robert Maxham

In the second sonata, No. 23, the fortepiano assumes the solo responsibility for the continuo part ( basso in the title). This work follows the pattern familiar from works by Tartini (and even Giovanni Battista Somis), of a moderately paced movement followed by one a bit faster and capped off by an even quicker one. Luks’s fortepiano, a modern instrument made after a 1726 instrument made by Bartolomeo Cristofori, matches Schayegh’s sonorities, though she displays a tonal richness in the lower registers that hardly found expression in Sonata No. 11.

Harpsichord and cello return in the slow movement (Adagio poco andante, which also features a cadenza at the end) from the Seventh Sonata, its poignant sensibility bleeding through the figuration surrounding the main melody. The same instrumentation composes the continuo grouping for the 13th Sonata, also cast in three movements (the first, slow, the second two, fast and faster). Schayegh’s notes suggest that while the heaviest encrustations of ornaments appear in slow movements, the fast ones display a wide variety of procedures of varying the material, and that may account for the greater simplicity of movements like this sonata’s final Allegro.

Sonata No. 32 opens with an Allegro that struts breathtakingly in double-stops but also features bursts of ornamentation, pyrotechnical display in Schayegh’s reading. The choice of fortepiano as the continuo instrument highlights the movement’s bounce. The slow movement throws a double punch near the end, with a buildup of figuration leading to a cadenza. The finale relies on melodic appeal rather than virtuosic bravado.

Schayegh’s tone, not always mellifluous, sounds a great deal different from the tart wheezing that earlier period practitioners might have produced, and Glossa’s engineers have captured it vividly, though the clarity they’ve brought to the recorded sound represents all the instruments in sharp focus. Schayegh’s program overlaps in only one Sonata (No. 23 in C Minor) the collection made by violinist Hans-Joachim Berg and harpsichord player Naoko Akutagawa on Naxos 8.572307 (also featuring period ornamentation, Fanfare 35:4). While I recommended their performances, listeners may find a warmer graciousness in Schayegh’s readings; the engineers for both make the violins sound somewhat abrasive. In reviewing violinist Anton Steck’s readings of six of Benda’s sonatas (none of which overlap with Schayegh’s program) with Christian Rieger, on CPO 777 214, Fanfare 32:1, I noted that Steck and Rieger’s instruments “produce consistently ingratiating textures, though there can be no mistaking Steck’s violin for a modern one.” And though he may be playing from an older edition, there’s no resisting his exuberant sparkle in the second movement of the opening Sonata in C Major. In that same review, I disparaged the textures produced by Ivan Zenatý and his ensemble (Pwre Hejnýy, cello, and Jaroslav T?ma, harpsichord, on Arta 1022-2111, which I reviewed in Fanfare 18:6. Zenatý plays with a great gusto, but many will feel that whatever he can do will necessarily fall short of the effect of the original ornaments. For those interested in exploring Benda’s work, in this native environment, Schayegh’s collection should provide a heady enough brew as an introduction, and because of the lack of significant overlap, should stand alongside Berg’s collection, their differences complementing each other in creating a richer understanding of the composer’s aim of creating a sweetly melodic repast, richly glazed. Highly recommended. -- Robert Maxham

DOWNLOAD FROM ISRA.CLOUD

Leila Schayegh, Vaclav Luks, Felix Knec - Franz Benda Violin Sonatas.rar - 430.1 MB

Leila Schayegh, Vaclav Luks, Felix Knec - Franz Benda Violin Sonatas.rar - 430.1 MB

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads