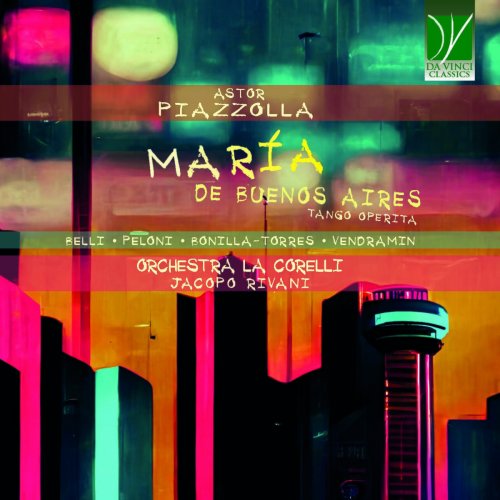

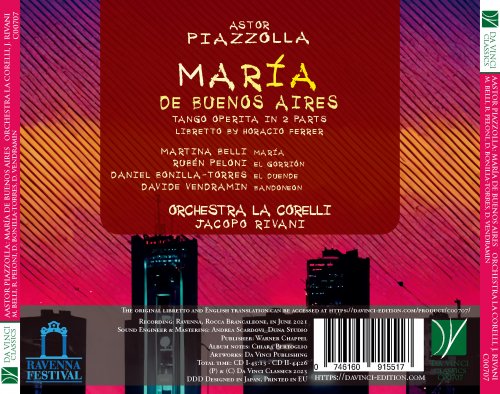

Davide Vendramin - Astor Piazzolla: María de Buenos Aires (Tango Operita) (2023)

BAND/ARTIST: Davide Vendramin, Jacopo Rivani, Orchestra La Corelli

- Title: Astor Piazzolla: María de Buenos Aires (Tango Operita)

- Year Of Release: 2023

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 87:41 min

- Total Size: 423 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

CD1:

01. María de Buenos Aires, Part I, Scene 1: "Alevare" (El Duende)

02. María de Buenos Aires, Part I, Scene 2: "Tema de María"

03. María de Buenos Aires, Part I, Scene 3a: "Balada renga para un organito loco" (El duende, Payador)

04. María de Buenos Aires, Part I, Scene 3b: "Yo soy María" (María)

05. María de Buenos Aires, Part I, Scene 4: "Milonga carrieguera por María la niña" (Gorríon, María)

06. María de Buenos Aires, Part I, Scene 5: "Fuga y misterio"

07. María de Buenos Aires, Part I, Scene 6: "Poema valseado" (María)

08. María de Buenos Aires, Part I, Scene 7: "Toccata rea" (El duende)

09. María de Buenos Aires, Part I, Scene 8: "Misere canyengue de los ladrones antiguos" (Antiguo ladrón, María)

CD2:

01. María de Buenos Aires, Part II, Scene 9: "Contramilonga a la funerala por la primera muerte de María" (El duende)

02. María de Buenos Aires, Part II, Scene 10: "Tangata del alba"

03. María de Buenos Aires, Part II, Scene 11: "Carta a los árboles y a las chimeneas" (Sombra de María)

04. María de Buenos Aires, Part II, Scene 12: "Aria de los analistas" (Analista Primero, Sombra de María)

05. María de Buenos Aires, Part II, Scene 13: "Romanza del duende poeta y curda" (El duende, Chorus)

06. María de Buenos Aires, Part II, Scene 14: "Allegro tangabile"

07. María de Buenos Aires, Part II, Scene 15: "Milonga de la anunciación" (Sombra de María)

08. María de Buenos Aires, Part II, Scene 16: "Tangus Dei" (Voz de ese domingo, El duende, Sombra de María)

The story of a person living in the streets of a merciless town. A story of violence, precociously experienced and marking the person’s outlook on life. A story of seduction, where the seducer is a musical instrument, and specifically the Bandoneon. These short sentences might summarize the plot of María de Buenos Aires, but also the early life of the opera’s composer, Astor Piazzolla.

It was particularly during the years Piazzolla spent in New York with his family – and certainly not in the most exclusive boroughs of the city – that young Astor had to fight for his life. He had been taught boxing by his father, and was certainly able to defend himself. He was not unacquainted with physical pain and life’s hardships; as a child, he had undergone several surgeries for bone problems, and, even though the last surgery proved resolutive, this experience left him with a feeling that life was hard, and that one had to fight for it and in it.

In this bleak context, a special light came to Astor Piazzolla’s life when he first “met” a bandoneon. An uncle of Astor was visiting New York together with him, and the boy was enthralled by the sight of that instrument in a shop window. It was a second-hand instrument, whose price could be afforded by the family – a mere eighteen dollars; Astor’s father, Vicente, who had Italian origins but whose heart was already Argentinian, was impressed by his son’s interest in music and, particularly, in an instrument which is almost identified with the Argentinian music tradition.

The bandoneon, similar in appearance and sound to an accordion, had come to Argentina as an immigrant in turn. Just as the Piazzolla family had Italian roots but came to represent the Argentinian soul like few others, so did the Bandoneon: created in Germany by Heinrich Band, it had crossed the Atlantic with a purpose very different from the use it would eventually find. It was, in fact, a “sacred” instrument, conceived as a portable, marching organ, suited for accompanying religious processions and festivals. From this exquisitely sacred function, the bandoneon became the identifying instrument for a quite different kind of worship. Brought to South America by European emigrants, it quickly became the iconic voice of the tango, as performed in the milongas, the “churches” of the tango.

Here again we have a parallel between Piazzolla’s life experience and that narrated in María de Buenos Aires: in a fashion which can strike as slightly blasphemous at times, or at least very bizarre, the sphere of the sacred and that of the “very secular” continuingly intersect.

Still, the true interpretation of Piazzolla’s operita, which is a kind of hyper homage to the world of tango, is not to be limited to the purposefully scandalous details of the libretto or to the desecrating titles of certain scenes of the work.

The key, indeed, is tango itself, conceived – as hinted before – in the fashion of a liturgy. This not only implies that, for tango enthusiast, this dance has become almost a religion. It also implies that the world of tango – with its rules, its steps, its roles, its ceremonies – is also a way for finding a meaning to life. This meaning is found in love and beauty; of course, love here is a very sensual kind of love, and beauty is somewhat restricted to the elegance of movement and to the hierarchization of roles and steps. Still, there is more to tango than a “mere dance”, and there is an aspiration to infinity, to transcendence, which is not easy to grasp for foreigners – who might be tempted to see just the patina, the slight varnish of sensuousness, neglecting what this stands for. Stealing concepts from Søren Kierkegaard’s interpretation of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, we might say that an obsession for seduction is but a way to express the infinite longing for the infinite, i.e. the first expression of transcendence.

Thus, what appears as blasphemy in María de Buenos Aires is, at least, “more than that”; and, perhaps, not even that.

The libretto is authored by Horacio Arturo Ferrer Ezcurra, a Uruguayan poet whose education took place between the two poles of literature and music. His poetic language developed in a very original fashion, and his style is characterized by a pronounced surrealism, partly due to his habit of creating fanciful neologisms.

The encounter between Ferrer’s unique poetical style and the world of (sung) tango could only be a fruitful one. Indeed, his verses were able to infuse new life into a language, that of tango, which was deemed by many to be already exhausted. His creation of lyrics for what would become La ultima Grela, by Anibal Troilo, became the foundational moment of his career as a poet for tango songs. When Piazzolla, in turn, encountered Ferrer’s poetry, it was love at first sight; the musician sought the poet’s collaboration, and, in 1967, their joint work began.

And their first cooperation was a masterpiece, i.e. precisely María de Buenos Aires. The extent of Ferrer’s involvement in its creation is indirectly demonstrated by the fact that he interpreted the character of El Duende, one of the most enigmatic and puzzling elements of the operita. On the other hand, the extent of Ferrer’s involvement in the world of tango is directly shown by the fact that his last grand enterprise was the creation of a National Academy of the Tango, with the purpose of promoting the study of tango and its dissemination worldwide. As Ferrer himself put it, “Tango flows within my veins since my birth; I would define my life as a kind of permanent festival. I believe that I’m a modest man, but I have a great virtue: there is harmony in my destiny. This harmony materialized itself in tango. One of the fundamental values of my life is freedom, and for me tango is an extraordinary exercise in freedom. It is the scent, taste, smell and art of sensuousness; its destiny is to express the confidential side of existence and bringing us back to the primordial instinct which is the freest component of ourselves”.

As said before, the first result of Ferrer and Piazzolla’s joint work was María de Buenos Aires, premiered at the Teatro Colon of Buenos Aires on May 8th, 1968, and which obtained such an immediate and long-lasting success that it became the most performed opera in Argentina. The team they built was ideally paired, in fact; Piazzolla’s music is characterized by the encounter of the traditional Argentinian tango, with jazz, the idiom of classical and that of contemporary music. The instruments employed by Piazzolla are likewise varied: those typical for the Western classical scene, like the violin and flute, are found side by side with an instrument typical for tango, such as the bandoneon, and others which had never been employed before for this music, such as drums and vibraphone. Similarly, Ferrer’s poetry is typical for his highly original style, with fantastic and surreal elements, an idiosyncratic use of temporality (expressed in particular by the different perception of time by María and by the other characters in the plot), and a mixture of sacred, secular, fantastic, mythological, magical, which seems to echo the multilingual musical idiom employed by Piazzolla.

There are many levels in Ferrer’s libretto: the story itself, the violated femininity of María and her wounds, the religious allusions, but also the hidden political subtext, decrying the institutions of his time, and also the way society behaves, with its corruption, both explicit and implicit, but equally poisonous for a healthy society. María is in fact not only herself, a destitute woman seduced by music and fallen in a life of vice, depravation, prostitution (while preserving a miraculous deep innocence), but also a symbol for the city itself, a kind of mythical phoenix which keeps dying and being reborn.

María, destined from birth to an unhappy life, falls in love with tango, which is much more than “just a dance” in the opera; it is a real character, perhaps more of a protagonist than the protagonist herself. Tango seduces and abandons her, leading her to prostitution and enthrallment. Her utter dependency from her “clients” is but the consequence of her dependency from tango, her true master. She undergoes a violent death, characterized by numerous abuses and Satanic perversions; but this death, which seems to put the seal to an equally unhappy life, is in fact a moment of rebirth. She becomes the shadow of her own, but, having lost her body, she somehow reconquers her virginity; she wanders within an infernal landscape, which is in turn the embodiment of her own city – and ultimately of herself.

Her presence is deeply felt by the inhabitants of the city, both human and non-human, as in the case of the Duende, who impregnates her so that she can give birth to a girl, who will be called María like her mother – and perhaps is the same María who gave her life.

Within this purposefully absurd and disquieting, anguished and troubled scenario, Piazzolla’s music contributes some unforgettable moments. The voice of Italian singer Milva, for whom the character of María was created, is indissolubly bound to the female protagonist; the unique mixture of warmth, passion, sensuousness, but also desperation and agony found in her timbre represent the embodiment of Piazzolla’s musical ideal. Around her, a carousel of forced happiness, darkness, dazzling colours and contradictions is given voice by Piazzolla’s music. The result is a unique work, as disconcerting as it is fascinating; it is the unique musical expression of an entire world, coming to the listener with the aggressive power of a revelation.

Chiara Bertoglio

It was particularly during the years Piazzolla spent in New York with his family – and certainly not in the most exclusive boroughs of the city – that young Astor had to fight for his life. He had been taught boxing by his father, and was certainly able to defend himself. He was not unacquainted with physical pain and life’s hardships; as a child, he had undergone several surgeries for bone problems, and, even though the last surgery proved resolutive, this experience left him with a feeling that life was hard, and that one had to fight for it and in it.

In this bleak context, a special light came to Astor Piazzolla’s life when he first “met” a bandoneon. An uncle of Astor was visiting New York together with him, and the boy was enthralled by the sight of that instrument in a shop window. It was a second-hand instrument, whose price could be afforded by the family – a mere eighteen dollars; Astor’s father, Vicente, who had Italian origins but whose heart was already Argentinian, was impressed by his son’s interest in music and, particularly, in an instrument which is almost identified with the Argentinian music tradition.

The bandoneon, similar in appearance and sound to an accordion, had come to Argentina as an immigrant in turn. Just as the Piazzolla family had Italian roots but came to represent the Argentinian soul like few others, so did the Bandoneon: created in Germany by Heinrich Band, it had crossed the Atlantic with a purpose very different from the use it would eventually find. It was, in fact, a “sacred” instrument, conceived as a portable, marching organ, suited for accompanying religious processions and festivals. From this exquisitely sacred function, the bandoneon became the identifying instrument for a quite different kind of worship. Brought to South America by European emigrants, it quickly became the iconic voice of the tango, as performed in the milongas, the “churches” of the tango.

Here again we have a parallel between Piazzolla’s life experience and that narrated in María de Buenos Aires: in a fashion which can strike as slightly blasphemous at times, or at least very bizarre, the sphere of the sacred and that of the “very secular” continuingly intersect.

Still, the true interpretation of Piazzolla’s operita, which is a kind of hyper homage to the world of tango, is not to be limited to the purposefully scandalous details of the libretto or to the desecrating titles of certain scenes of the work.

The key, indeed, is tango itself, conceived – as hinted before – in the fashion of a liturgy. This not only implies that, for tango enthusiast, this dance has become almost a religion. It also implies that the world of tango – with its rules, its steps, its roles, its ceremonies – is also a way for finding a meaning to life. This meaning is found in love and beauty; of course, love here is a very sensual kind of love, and beauty is somewhat restricted to the elegance of movement and to the hierarchization of roles and steps. Still, there is more to tango than a “mere dance”, and there is an aspiration to infinity, to transcendence, which is not easy to grasp for foreigners – who might be tempted to see just the patina, the slight varnish of sensuousness, neglecting what this stands for. Stealing concepts from Søren Kierkegaard’s interpretation of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, we might say that an obsession for seduction is but a way to express the infinite longing for the infinite, i.e. the first expression of transcendence.

Thus, what appears as blasphemy in María de Buenos Aires is, at least, “more than that”; and, perhaps, not even that.

The libretto is authored by Horacio Arturo Ferrer Ezcurra, a Uruguayan poet whose education took place between the two poles of literature and music. His poetic language developed in a very original fashion, and his style is characterized by a pronounced surrealism, partly due to his habit of creating fanciful neologisms.

The encounter between Ferrer’s unique poetical style and the world of (sung) tango could only be a fruitful one. Indeed, his verses were able to infuse new life into a language, that of tango, which was deemed by many to be already exhausted. His creation of lyrics for what would become La ultima Grela, by Anibal Troilo, became the foundational moment of his career as a poet for tango songs. When Piazzolla, in turn, encountered Ferrer’s poetry, it was love at first sight; the musician sought the poet’s collaboration, and, in 1967, their joint work began.

And their first cooperation was a masterpiece, i.e. precisely María de Buenos Aires. The extent of Ferrer’s involvement in its creation is indirectly demonstrated by the fact that he interpreted the character of El Duende, one of the most enigmatic and puzzling elements of the operita. On the other hand, the extent of Ferrer’s involvement in the world of tango is directly shown by the fact that his last grand enterprise was the creation of a National Academy of the Tango, with the purpose of promoting the study of tango and its dissemination worldwide. As Ferrer himself put it, “Tango flows within my veins since my birth; I would define my life as a kind of permanent festival. I believe that I’m a modest man, but I have a great virtue: there is harmony in my destiny. This harmony materialized itself in tango. One of the fundamental values of my life is freedom, and for me tango is an extraordinary exercise in freedom. It is the scent, taste, smell and art of sensuousness; its destiny is to express the confidential side of existence and bringing us back to the primordial instinct which is the freest component of ourselves”.

As said before, the first result of Ferrer and Piazzolla’s joint work was María de Buenos Aires, premiered at the Teatro Colon of Buenos Aires on May 8th, 1968, and which obtained such an immediate and long-lasting success that it became the most performed opera in Argentina. The team they built was ideally paired, in fact; Piazzolla’s music is characterized by the encounter of the traditional Argentinian tango, with jazz, the idiom of classical and that of contemporary music. The instruments employed by Piazzolla are likewise varied: those typical for the Western classical scene, like the violin and flute, are found side by side with an instrument typical for tango, such as the bandoneon, and others which had never been employed before for this music, such as drums and vibraphone. Similarly, Ferrer’s poetry is typical for his highly original style, with fantastic and surreal elements, an idiosyncratic use of temporality (expressed in particular by the different perception of time by María and by the other characters in the plot), and a mixture of sacred, secular, fantastic, mythological, magical, which seems to echo the multilingual musical idiom employed by Piazzolla.

There are many levels in Ferrer’s libretto: the story itself, the violated femininity of María and her wounds, the religious allusions, but also the hidden political subtext, decrying the institutions of his time, and also the way society behaves, with its corruption, both explicit and implicit, but equally poisonous for a healthy society. María is in fact not only herself, a destitute woman seduced by music and fallen in a life of vice, depravation, prostitution (while preserving a miraculous deep innocence), but also a symbol for the city itself, a kind of mythical phoenix which keeps dying and being reborn.

María, destined from birth to an unhappy life, falls in love with tango, which is much more than “just a dance” in the opera; it is a real character, perhaps more of a protagonist than the protagonist herself. Tango seduces and abandons her, leading her to prostitution and enthrallment. Her utter dependency from her “clients” is but the consequence of her dependency from tango, her true master. She undergoes a violent death, characterized by numerous abuses and Satanic perversions; but this death, which seems to put the seal to an equally unhappy life, is in fact a moment of rebirth. She becomes the shadow of her own, but, having lost her body, she somehow reconquers her virginity; she wanders within an infernal landscape, which is in turn the embodiment of her own city – and ultimately of herself.

Her presence is deeply felt by the inhabitants of the city, both human and non-human, as in the case of the Duende, who impregnates her so that she can give birth to a girl, who will be called María like her mother – and perhaps is the same María who gave her life.

Within this purposefully absurd and disquieting, anguished and troubled scenario, Piazzolla’s music contributes some unforgettable moments. The voice of Italian singer Milva, for whom the character of María was created, is indissolubly bound to the female protagonist; the unique mixture of warmth, passion, sensuousness, but also desperation and agony found in her timbre represent the embodiment of Piazzolla’s musical ideal. Around her, a carousel of forced happiness, darkness, dazzling colours and contradictions is given voice by Piazzolla’s music. The result is a unique work, as disconcerting as it is fascinating; it is the unique musical expression of an entire world, coming to the listener with the aggressive power of a revelation.

Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2023 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads