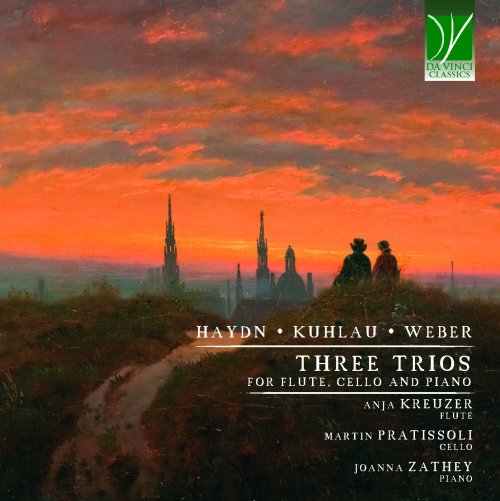

Anja Kreuzer, Martin Pratissoli, Joanna Zathey - Haydn, Kuhlau, Weber: Three Trios (For Flute, Cello and Piano) (2023)

BAND/ARTIST: Anja Kreuzer, Martin Pratissoli, Joanna Zathey

- Title: Haydn, Kuhlau, Weber: Three Trios (For Flute, Cello and Piano)

- Year Of Release: 2023

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:59:30

- Total Size: 240 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

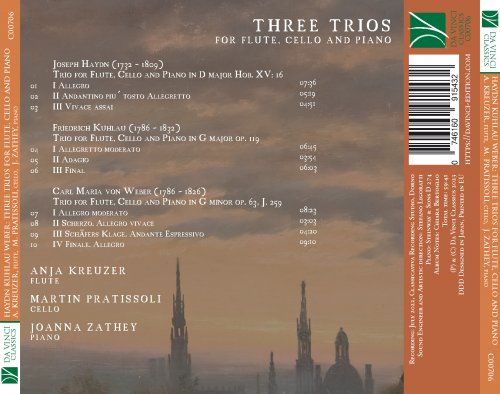

Tracklist

01. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in D Major, Hob. XV: 16 : I. Allegro

02. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in D Major, Hob. XV: 16 : II. Andantino piu´ tosto Allegretto

03. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in D Major, Hob. XV: 16 : III. Vivace assai

04. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Major, Op. 119: I. Allegretto moderato

05. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Major, Op. 119: II. Adagio

06. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Major, Op. 119: III. Final

07. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Minor, Op. 63, J. 259: I. Allegro moderato

08. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Minor, Op. 63, J. 259: II. Scherzo. Allegro vivace

09. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Minor, Op. 63, J. 259: III. Schäfers Klage. Andante Espressivo

10. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Minor, Op. 63, J. 259: IV. Finale. Allegro

When budding musicians begin studying music theory, they are told that sound has three main characteristics, i.e. height/pitch, intensity, and duration. Timbre is also mentioned, but is also somewhat quickly forgotten. Of these three parameters, in fact, it seems the most expendable. A tune can be transposed and sound “almost” the same, provided that the intervals are respected; but this impression of “almost” identity is quickly lost if the transposition involves a change in register, for example exceeding one octave. The same tune, played fortissimo or pianissimo sounds completely different. Durations also can be respected proportionally, without thereby destroying the line of a tune too much, but even there, a pronounced inflation or deflation of the musical time effectively renders the music unrecognizable or unintelligible.

Seemingly, a change in timbre affects the music least, unless it is between entirely incongruent instruments; but even so, a melody may remain recognizable and identifiable if played on, say, the piccolo or the double bass.

Still, every instrument has its own idiosyncrasies. It has registers in which it sounds better and worse, in which it is more or less powerful, more or less brilliant, more or less difficult to play. There are things a particular instrument simply cannot do, and others which may seem feasible, but then, when played, either are extremely uncomfortable, or extremely odd-sounding, or extremely complex. (This does not mean, of course, renouncing technical challenges: what is unplayable for one generation, may become almost standard practice for the next). There are specific passages and musical gestures which are typical for a particular instrument or group of instruments, and which practically identify the instrument playing it even just on paper. One cannot play pizzicato on a wind instrument, or use the resonance of the piano pedal on a violin (even though a violin playing with a piano may benefit from the latter’s pedal resonance).

To write a chamber music piece, therefore, implies knowing perfectly the pluses and minuses of every instrument, and to manage them in order for them to become resources rather than handicaps. A skilled composer will derive from the strength and weaknesses of the instruments he or she is employing some musical ideas, which would otherwise remain only a potential.

This, however, can happen within limits. A chamber music piece entirely built on what is specific of the instruments playing it, on their idiosyncrasies and uniqueness, is hardly likely to be a consistent piece of music. There are examples, in contemporary music, of works structured on sound effects, where in fact the prompting comes almost exclusively from the specificity of each instrument. But these are recent examples, which have virtually no precedents in the history of earlier chamber music. The alchemic process of creating the perfect piece of chamber music must therefore take into consideration the pros and cons of every instrument, what they can and cannot do, and build the result on the common denominator of what they share, without flattening their diversity and renouncing their individual voices.

This is particularly complex in the case of three instruments, all of which belong to different families, and which have different registers, sounds, techniques. This happens with the trio for piano, cello and flute, and the difficulty for the players is further increased when playing on modern instruments, since what was balanced in the eyes and ears of a composer working with a fortepiano, a gut-stringed cello and a transverse flute becomes much more complex when playing on a modern grand, a modern cello, and a modern metal flute.

Both the cello and the flute have a favoured range, though both (but especially the cello) have a considerable extension. However, one could roughly say that the cello’s range corresponds to that normally covered by the piano’s left hand, and the flute’s range to that played by the right. The piano, therefore, unites the ranges of the other two instruments; thanks to the pianist’s two hands, it is as if the piano counted as two instruments – building up a quartet – rather than just as a third. However, the flute cannot normally play more than one note at a time, different from the piano and, partially, from the cello; both the cello and the flute are limited by their needs regarding phrasing (the need to breathe for the flutist and to change bow for the cello), but, at the same time, they can sustain a note’s sound in a fashion which is simply impossible on the piano, and was even more dramatically felt on the fortepiano.

The three works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album demonstrate the composers’ struggle to find this perfect alchemy, and their eventual success in finding it.

Franz Joseph Haydn is one of the greatest composers of chamber music in the eighteenth century and in the entire history of the Western musical literature, but his most important chamber music master pieces are found in the genre of the string quartet, which he is credited with the merit of practically creating. He also wrote several piano trios, among others, which in most cases are conceived for a trio with violin and cello, besides the keyboard. Others were written for flute, cello and piano, but the degree of compulsoriness attached to their instrumentation is varied. Haydn’s flute trios do certainly consider the flute’s presence as an identification mark, especially since they were prepared with a clear “marketing” strategy in mind. The English nobility, in fact, was the prey of a flute craze; indeed, the flute is perhaps the instrument with the best “quality/price” ratio– meaning, by “quality”, the musical result one can reach for a comparatively low “price”, i.e. musical effort and application. The flute allowed the English aristocracy to play rather complex works without having to master a professional’s technical skills. Making music together, furthermore, was one of the most pleasant activities a nobleman could do, and the shared pleasure of music-making nourished a market which was constantly on the look for new music.

Haydn wrote three Flute Trios, indicated as Hob. XV: 15-17, of which the one recorded here, i.e. no. 16, is the second, though it was indicated as the first in an advertisement published on the Morning Herald on February 22nd, 1792. Cleverly, though perhaps not entirely innocently, Haydn had these works published almost simultaneously in England, by John Bland, and in Vienna, by his reference publisher Artaria. Bland was partly responsible for the creation of these Trios: having visited Haydn at his place in 1789, he had encouraged the composer to undertake the task of writing for the flute, considering how successful this genre was at the time in his country. Curiously, Bland appended an advertisement against musical piracy to his published edition of the trios, even though, rigorously, he was responsible for an act of “copyright infringement” (as we would say now) against the rights of his competitor Artaria.

These works were also connected with Haydn’s journeys to London, following his moving to Vienna in 1790/1, and the dismantlement of the Esterházy orchestra for which he had worked over an extensive period of time.

With his extreme contrapuntal skills and the ability he had acquired in handling the four parts of the String Quartet, Haydn was able to manage a consistent handling of the four (and more) parts of the Piano trio with flute. However, the tradition already existing in this field discouraged too independent a use of the three instruments. The flute was frequently in dialogue with the piano’s right hand, while the cello often doubled, in a fashion similar to continuo writing, the part of the left hand. Haydn increased their independency, but was perhaps slightly less audacious in this field than in others. Indeed, the very intended destination of these trios (i.e. a readership of skilled amateurs) discouraged too daring a use of innovations.

A more exciting treatment of the parts is found in Friedrich Kuhlau’s Grand Trio op. 119, but the reason is that this work had been originally conceived for two flutes and piano. The two wind instruments, therefore, were treated as equals, and had similarly demanding parts. When transferring the second flute’s part to the bass, in order for it to be played by the cello (or even by the bassoon), the comparative virtuosity and independency of the original part was maintained. Here, the cello is really a peer of the other instruments; moreover, Kuhlau’s extensive writing for the flute (he composed many beautiful solo pieces for this instrument) encouraged him to demand very much from the player, and thus, in consequence, to create beautiful and challenging pieces. This Trio is one of Kuhlau’s last works, composed in 1831, just one year before his death. It is therefore suffused with Romantic tinges, in spite of a composition style which is rather light and transparent.

It was preceded by more than ten years by a Trio which, in fact, sounds perhaps even more modern. Composed by Carl Maria von Weber, who was born in the same year as Kuhlau, it is a sparkling and brilliant piece, perhaps its composer’s masterpiece in the field of chamber music. It is loaded with quotations and references: on the one hand, its third movement, subtitled Shepherd’s Lament, employs as its foundation a Lied by Wilhelm Ehler, composed for voice and guitar on lyrics by Johann von Goethe, which had been set to music by many other composers. On the other hand, the most evident references are those to Weber’s own Freischütz, his undisputed masterpiece, which was in the making when this Trio was written. Among such references, we might mention the motif of the devil’s trill, found in Caspar’s drinking song and here in the Trio’s finale, or a quote from the chorus Laßt lustig die Hörner ercschallen, again in the Finale.

Here the three instruments are treated fully as equals, and, moreover, different from the other pieces recorded here no alternative version for other ensembles has been created or authorized by the composer. This is quintessentially a Trio for flute, cello and piano, and we can appreciate the level of refinement with which Weber treated each instrument as well as the combination of the three. Together, these three trios are among the most beautiful in the literature for this relatively rare instrumental combination, and they allow us to explore, together with their composers, the unheard-of possibilities of this ensemble and of this genre.

01. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in D Major, Hob. XV: 16 : I. Allegro

02. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in D Major, Hob. XV: 16 : II. Andantino piu´ tosto Allegretto

03. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in D Major, Hob. XV: 16 : III. Vivace assai

04. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Major, Op. 119: I. Allegretto moderato

05. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Major, Op. 119: II. Adagio

06. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Major, Op. 119: III. Final

07. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Minor, Op. 63, J. 259: I. Allegro moderato

08. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Minor, Op. 63, J. 259: II. Scherzo. Allegro vivace

09. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Minor, Op. 63, J. 259: III. Schäfers Klage. Andante Espressivo

10. Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano in G Minor, Op. 63, J. 259: IV. Finale. Allegro

When budding musicians begin studying music theory, they are told that sound has three main characteristics, i.e. height/pitch, intensity, and duration. Timbre is also mentioned, but is also somewhat quickly forgotten. Of these three parameters, in fact, it seems the most expendable. A tune can be transposed and sound “almost” the same, provided that the intervals are respected; but this impression of “almost” identity is quickly lost if the transposition involves a change in register, for example exceeding one octave. The same tune, played fortissimo or pianissimo sounds completely different. Durations also can be respected proportionally, without thereby destroying the line of a tune too much, but even there, a pronounced inflation or deflation of the musical time effectively renders the music unrecognizable or unintelligible.

Seemingly, a change in timbre affects the music least, unless it is between entirely incongruent instruments; but even so, a melody may remain recognizable and identifiable if played on, say, the piccolo or the double bass.

Still, every instrument has its own idiosyncrasies. It has registers in which it sounds better and worse, in which it is more or less powerful, more or less brilliant, more or less difficult to play. There are things a particular instrument simply cannot do, and others which may seem feasible, but then, when played, either are extremely uncomfortable, or extremely odd-sounding, or extremely complex. (This does not mean, of course, renouncing technical challenges: what is unplayable for one generation, may become almost standard practice for the next). There are specific passages and musical gestures which are typical for a particular instrument or group of instruments, and which practically identify the instrument playing it even just on paper. One cannot play pizzicato on a wind instrument, or use the resonance of the piano pedal on a violin (even though a violin playing with a piano may benefit from the latter’s pedal resonance).

To write a chamber music piece, therefore, implies knowing perfectly the pluses and minuses of every instrument, and to manage them in order for them to become resources rather than handicaps. A skilled composer will derive from the strength and weaknesses of the instruments he or she is employing some musical ideas, which would otherwise remain only a potential.

This, however, can happen within limits. A chamber music piece entirely built on what is specific of the instruments playing it, on their idiosyncrasies and uniqueness, is hardly likely to be a consistent piece of music. There are examples, in contemporary music, of works structured on sound effects, where in fact the prompting comes almost exclusively from the specificity of each instrument. But these are recent examples, which have virtually no precedents in the history of earlier chamber music. The alchemic process of creating the perfect piece of chamber music must therefore take into consideration the pros and cons of every instrument, what they can and cannot do, and build the result on the common denominator of what they share, without flattening their diversity and renouncing their individual voices.

This is particularly complex in the case of three instruments, all of which belong to different families, and which have different registers, sounds, techniques. This happens with the trio for piano, cello and flute, and the difficulty for the players is further increased when playing on modern instruments, since what was balanced in the eyes and ears of a composer working with a fortepiano, a gut-stringed cello and a transverse flute becomes much more complex when playing on a modern grand, a modern cello, and a modern metal flute.

Both the cello and the flute have a favoured range, though both (but especially the cello) have a considerable extension. However, one could roughly say that the cello’s range corresponds to that normally covered by the piano’s left hand, and the flute’s range to that played by the right. The piano, therefore, unites the ranges of the other two instruments; thanks to the pianist’s two hands, it is as if the piano counted as two instruments – building up a quartet – rather than just as a third. However, the flute cannot normally play more than one note at a time, different from the piano and, partially, from the cello; both the cello and the flute are limited by their needs regarding phrasing (the need to breathe for the flutist and to change bow for the cello), but, at the same time, they can sustain a note’s sound in a fashion which is simply impossible on the piano, and was even more dramatically felt on the fortepiano.

The three works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album demonstrate the composers’ struggle to find this perfect alchemy, and their eventual success in finding it.

Franz Joseph Haydn is one of the greatest composers of chamber music in the eighteenth century and in the entire history of the Western musical literature, but his most important chamber music master pieces are found in the genre of the string quartet, which he is credited with the merit of practically creating. He also wrote several piano trios, among others, which in most cases are conceived for a trio with violin and cello, besides the keyboard. Others were written for flute, cello and piano, but the degree of compulsoriness attached to their instrumentation is varied. Haydn’s flute trios do certainly consider the flute’s presence as an identification mark, especially since they were prepared with a clear “marketing” strategy in mind. The English nobility, in fact, was the prey of a flute craze; indeed, the flute is perhaps the instrument with the best “quality/price” ratio– meaning, by “quality”, the musical result one can reach for a comparatively low “price”, i.e. musical effort and application. The flute allowed the English aristocracy to play rather complex works without having to master a professional’s technical skills. Making music together, furthermore, was one of the most pleasant activities a nobleman could do, and the shared pleasure of music-making nourished a market which was constantly on the look for new music.

Haydn wrote three Flute Trios, indicated as Hob. XV: 15-17, of which the one recorded here, i.e. no. 16, is the second, though it was indicated as the first in an advertisement published on the Morning Herald on February 22nd, 1792. Cleverly, though perhaps not entirely innocently, Haydn had these works published almost simultaneously in England, by John Bland, and in Vienna, by his reference publisher Artaria. Bland was partly responsible for the creation of these Trios: having visited Haydn at his place in 1789, he had encouraged the composer to undertake the task of writing for the flute, considering how successful this genre was at the time in his country. Curiously, Bland appended an advertisement against musical piracy to his published edition of the trios, even though, rigorously, he was responsible for an act of “copyright infringement” (as we would say now) against the rights of his competitor Artaria.

These works were also connected with Haydn’s journeys to London, following his moving to Vienna in 1790/1, and the dismantlement of the Esterházy orchestra for which he had worked over an extensive period of time.

With his extreme contrapuntal skills and the ability he had acquired in handling the four parts of the String Quartet, Haydn was able to manage a consistent handling of the four (and more) parts of the Piano trio with flute. However, the tradition already existing in this field discouraged too independent a use of the three instruments. The flute was frequently in dialogue with the piano’s right hand, while the cello often doubled, in a fashion similar to continuo writing, the part of the left hand. Haydn increased their independency, but was perhaps slightly less audacious in this field than in others. Indeed, the very intended destination of these trios (i.e. a readership of skilled amateurs) discouraged too daring a use of innovations.

A more exciting treatment of the parts is found in Friedrich Kuhlau’s Grand Trio op. 119, but the reason is that this work had been originally conceived for two flutes and piano. The two wind instruments, therefore, were treated as equals, and had similarly demanding parts. When transferring the second flute’s part to the bass, in order for it to be played by the cello (or even by the bassoon), the comparative virtuosity and independency of the original part was maintained. Here, the cello is really a peer of the other instruments; moreover, Kuhlau’s extensive writing for the flute (he composed many beautiful solo pieces for this instrument) encouraged him to demand very much from the player, and thus, in consequence, to create beautiful and challenging pieces. This Trio is one of Kuhlau’s last works, composed in 1831, just one year before his death. It is therefore suffused with Romantic tinges, in spite of a composition style which is rather light and transparent.

It was preceded by more than ten years by a Trio which, in fact, sounds perhaps even more modern. Composed by Carl Maria von Weber, who was born in the same year as Kuhlau, it is a sparkling and brilliant piece, perhaps its composer’s masterpiece in the field of chamber music. It is loaded with quotations and references: on the one hand, its third movement, subtitled Shepherd’s Lament, employs as its foundation a Lied by Wilhelm Ehler, composed for voice and guitar on lyrics by Johann von Goethe, which had been set to music by many other composers. On the other hand, the most evident references are those to Weber’s own Freischütz, his undisputed masterpiece, which was in the making when this Trio was written. Among such references, we might mention the motif of the devil’s trill, found in Caspar’s drinking song and here in the Trio’s finale, or a quote from the chorus Laßt lustig die Hörner ercschallen, again in the Finale.

Here the three instruments are treated fully as equals, and, moreover, different from the other pieces recorded here no alternative version for other ensembles has been created or authorized by the composer. This is quintessentially a Trio for flute, cello and piano, and we can appreciate the level of refinement with which Weber treated each instrument as well as the combination of the three. Together, these three trios are among the most beautiful in the literature for this relatively rare instrumental combination, and they allow us to explore, together with their composers, the unheard-of possibilities of this ensemble and of this genre.

Year 2023 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads