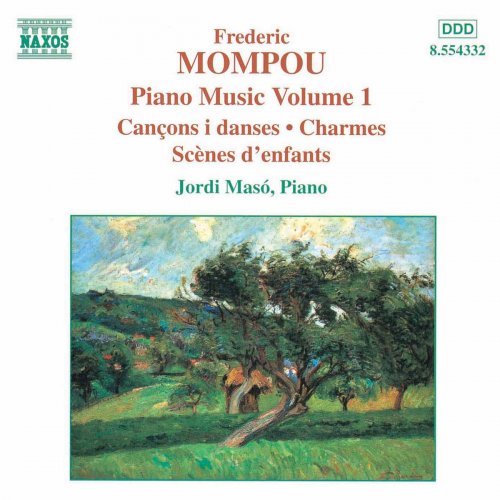

Jordi Masó - Mompou: Piano Music, Vol. 1 (1998)

BAND/ARTIST: Jordi Masó

- Title: Mompou: Piano Music, Vol. 1

- Year Of Release: 1998

- Label: Naxos

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:12:21

- Total Size: 195 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. I

02. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. II

03. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. III

04. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. IV

05. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. V

06. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. VI

07. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. VII

08. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. VIII

09. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. IX

10. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. X

11. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. XI

12. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. XII

13. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. XIV

14. Charmes: I. Pour endormir la souffrance

15. Charmes: II. Pour penetrer les ames

16. Charmes: III. Pour inspirer l'amour

17. Charmes: IV. Pour les guerisons

18. Charmes: V. Pour evoquer l'image du passe

19. Charmes: VI. Pour appeler la joie

20. Scenes d'enfants: I. Cris dans la rue

21. Scenes d'enfants: II. Jeux sur la plage

22. Scenes d'enfants: III. Jeu II

23. Scenes d'enfants: IV. Jeu III

24. Scenes d'enfants: V. Jeunes filles au jardin

Although Adolfo Salazar praised the "agreeable colouring" resulting from the "experiments on the keyboard" of Frederic Mompou, the great Madrid critic saw something suspicious in this Catalan composer he had turned his back on everything which appeared to be truly essential to the mainstream of great European music, and what defines great creators and able craftsmen alike, Neither counterpoint, fugue, orchestration, or thematic and formal development appear to have ever held the least interest for the composer of Cancons i Danses. But is this a criterion for judging the work of a composer who adopts an aesthetic position based precisely on the apparent renunciation of those values? Mompou did not want to compose like Cesar Franck, - even less like Schoenberg, and if his lack of ambition was no obstacle to his becoming a composer of some merit, it is because of the perfect marriage between his means and his ends. Salazar's criticism reminds us of the judgement of Rene Leibowitz concerning Chopin: the Polish composer would always be in reality just an amateur composer (albeit an amateur of genius). In both cases, it is understandable that thinkers of such rigidly held (though sometimes misguided) views should harbour such suspicions. In both instances, although on a different scale, it is how the music affects us, and not some opposing theory, which silences any verdict reached.

The career of Frederic Mompou, born in Barcelona in 1893, was typical of composers of his generation, but he clearly stands out from the others for his originality. His mother's family, of French origin and owners of the Dencausse bell foundry, was to have a decisive importance in the sentimental education of the composer. His attraction for French culture, a preference more Manichean than passionate; he once proclaimed French music as true and German music as false, is shared by nearly all his Catalan contemporaries, except Roberto Gerhard, but his direct knowledge of the fascinating sound world of bells was a much more personal characteristic which was to give him the unmistakable colouring of his most beautiful chords. Hearing Faure performing his own music in Barcelona was one of the great influences on his life, and the advanced level he was reaching as a pianist made his dream to go to Paris to study in the Conservatoire, directed at that time by Faure himself, perfectly feasible, but his almost pathological shyness prevented him from even applying for admission. Instead, he took private lessons from the great pianist Ferdinand Motte-Lacroix. Mompou therefore never followed any conventional studies of counterpoint, fugue and composition. The peculiarities of his character were also soon to bar the way to the possibility of a career as a concert pianist. For ever shut in in his own aesthetic world, but also arousing growing admiration in Motte-Lacroix and other French musicians, Mompou composed and began to find success by performing his works in the most exclusive Parisian salons. His success was confirmed by the appearance in 1921 of a famous article by the influential critic Emile Vuillermoz, defender in France of the causes not only of Debussy and Ravel, but also of Schoenberg and Stravinsky. The authority of Vuillermoz makes his final judgement all the more impressive. "The only disciple and successor to the composer of La Mer (… ) is surely the young Spaniard Frederic Mompou, who, without ever having known Debussy, has understood and absorbed the essence of his teaching."

Vuillermoz's text, a remarkable mixture of analytic precision and literary quality quite uncommon in writing of this kind, represents a practically definitive description of Mompou's style and artistic personality. His return to Barcelona, where he was to remain for the rest of his life in some isolation and with periods of total silence, was not to bring any significant changes in his musical language, He was to become a rather patriarchal figure, somewhat remote, even alien, to the young Catalan composers who tried to assimilate, perhaps with more failure than success, the styles of the European vanguard. Mompou had a characteristic beyond their reach: that of being a composer performed and listened to spontaneously by the highly conservative public of his country. His works even featured in the syllabuses of the Barcelona Conservatory (and still do), and are played by an endless number of students. Whether the criticism of his lack of interest in the new musical styles is legitimate or not, nobody can deny Mompou's qualities which define him as a genuine artist in the highest sense of this word: the possession of a personal poetry, his own unmistakeable sound, discovered through direct contact with the sound of the piano, and the way in which he found in this an expression of his inner world, formed from a mixture of such disparate elements as great Catalan mystical poetry and love of the atmosphere of the maritime quarters which he knew in the Barcelona of his childhood, in which the advance of civilization is imposed on the continuance of a pre-capitalist life, and where the relationship of the individual with traditional music could still be immediate. In fact he gave the name Barri de platja (beach quarter) to the chord G flat, C, E flat, A flat, D, which, for him, was the essence of all his music. In its sonority it surely tries to reproduce the sound of the familiar bells and the distant cries of the seagulls, mixing with those of the children playing near the onlooker, who, although alone, lovingly contemplates the colourful scene of the people by the sea and finds in it something of deep significance.

It is this love for popular Catalan culture that makes Mompou's Cancons i Danses (Songs and Dances) one of his most important works. At least they are, of all his creations, the best-known in his own country, and the fact that their composition spreads over nearly the whole of his life, from 1918 to 1962, makes them all the more interesting. The pairing of a slow song followed by a more animated dance reminds one of the combination of prelude and fugue, or dances such as the Hungarian Csardas. The thirteen pieces written for piano, almost the only instrument Mompou composed for (Canco i Dansa No. 13 also exists for guitar, and No.15 for organ) on the whole represent adaptations of popular Catalan songs. If setting traditional tunes to harmony is very common amongst composers of his time, Mompou shines in this art: his ability to give a song a harmony which appears simple and natural, but at the same time original and highly sophisticated, is one of his greatest secrets. The chords may be common, but often sweet and sonorous dissonances colour them, frequently in the form of an added upper melody with an unpredictable line which appears to emerge from the very excitation of the resonance of the natural harmonics, a technique which constitutes the true counterpoint of Mompou. Amongst the songs used are La Filla del Carmesi, and Dansa de Castelltercol (Canco i Dansa No. I), Senyora Isabel i Galop de Cortesia (No.2), El Noi de la Mare (Canco No.3), El Mariner i Ball del Ciri (Canco i Dansa No.4), Muntanyes Regalades and L 'Hereu Riera (No, 7), El Testament d'Amelia and La Filadora (No.8), El Rossinuyol (Canco No.9), Ball de l'Aliga i Turcs I cavallets, both of which come from the dances of the fiestas of the Patum de Berga (Canco i Dansa No. 11), La Dama d'Arag6 and La Mala Nova (No. 12) and Canco del Lladre (Canco No. 14). But not all these pieces are based on the rich universe of Catalan song. The Canco i Dansa No. 10, showing other less well-known concerns of Mompou, uses two Cantigas of Alfonso x. The rest are of original inspiration. If the sounds of his homeland are omnipresent (Dansa No.5 could easily be taken for another popular song, while Dansa No.3 is a sardana, the most characteristic dance of Catalonia, known to be salvaged from an unfinished string quartet, and Dansa No.9 almost quotes popular themes as in Dansa No. 14), in other cases the stylistic references are broader: Canco No.5, conceived during a dream, sounds like an ancient chant, full of austere solemnity and Canco i Dansa No.6 use West Indian rhythms, which also greatly influenced Xavier Montsalvatge, a Barcelona composer of a somewhat younger generation than Mompou.

Although Mompou is perhaps best-known for his adaptation of popular songs, the Catalan composer often had more abstract conceptions, in which he wanted to reflect his own particular interest in the transcendence reflected in mystic poetry or related texts. Although Mompou originally gave the title Karmas to a group of six pieces composed between 1920 and 1921, on realising that the Indian word did not exactly mean what he had imagined, he changed it for Charmes, in the sense of enchantment, a trance-like state caused by a spell. The French titles owe a debt to those which Debussy gave to his Preludes or Etudes … pour endormir la souffrance, pour penetrer les ames, pour inspirer l 'amour, pour les guerissons, pour evoquer l'image du passe, pour appeler la joie. In almost all the pieces an initial harmonic situation is held with small variations which do not give it a discursive sense, but manage to keep the listener in a hypnotic state, in which time seems to stand still. In the first of the Charmes (To Ease Suffering) an ostinato acompaniment is gradually modified until it appears in the most serious register of the piano, and establishing a framework of austere dissonance above which is repeated almost without variation a short melodic fragment. The second (To Penetrate Souls) features a slow melody of only five notes which are repeated in many different ways without losing their character of growing intensity, culminating in the dissonance of the fourth note, the most intense dissonace of all. In the third piece (To Inspire Love) an energetic ascending theme, harmonically almost identical to the Barri de Platja chord, serves as a backdrop for a slow recitative. A second section introduces a cheerful ostinato above which a cantilena of very sharp notes is developed. The dissolving of the ostinato prepares for the recapitulation of the first part. The fourth Charme (For Healing) is made up of a melody in dotted rhythm appearing above two different ostinati with the muffled beat of a chord without melody. The fifth (To Evoke Images of the Past) is divided into two parts: in the first, undulating arpeggios appearing to imitate the natural resonances of the harmonics sustain a prolonged melody; in the second, a new, progressively changing ostinato introduces first a new melody, then recalls that of the first part. The last of The Charmes (To Invoke Joy) matches its title with a leaping, unaccompanied melody leading to an animated dance, not far removed from any of those which feature in the Cancons i Danses. The piece ends with a return to the first melody, now against a background of chords.

During Mompou's successful years in Paris one of the works which most captivated his public was the one which carried the Schumann-like title Scenes d'enfants (Scenes of childhood). In fact it consists of the Three Jeux (games) he composed in 1915, to which he added the opening piece Cris dans la rue (Cries in the Street), and, as an ending, the well-known Jeunes filles au jardin (Girls in the Garden). The two movements which serve as a framework use the Catalan song La Filla del Marxant, which gives the work a cyclical character, in the form of an arc which opens and closes. Cris dans la rue depicts wild games based on a children's tune harmonized with rich overlays of fourths and fifths. A second melody leads to the first version of La Filla del Marxant, which is replaced by the initial chatter which appears to fade into the distance. The first of The Three Jeux, entitled Jeux sur la Plage (Games on the Beach) begins and ends with what could be the cries of birds or children running around on the seashore. The main body of the piece is dedicated to a children’s' song which recurs in a circular way with a rocking rhythm. The second Jeu begins and ends with distant cries. This time the song's rhythm becomes rather passionate, while in the third Jeu, identical in structure to those which preceded it, it gathers strength until it reaches a high pitch of emotional intensity. The sadness which floats between the games (perhaps that of the observer who can no longer participate in them) permeates the beginning of Jeunes Filles au Jardin in which ring out some of the most fascinating cries of the many which the work contains. A prolonged melody, full of a sweet serenity, is cut off by the return of the initial cries, which lead on to the new version of La Filla del Marxant. The repetition of the opening passage marks the end of Scenes d’enfants, one of the most frequently performed of all the works of this fascinating composer.

01. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. I

02. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. II

03. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. III

04. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. IV

05. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. V

06. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. VI

07. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. VII

08. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. VIII

09. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. IX

10. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. X

11. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. XI

12. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. XII

13. Cancons i danses: Canco i dansa No. XIV

14. Charmes: I. Pour endormir la souffrance

15. Charmes: II. Pour penetrer les ames

16. Charmes: III. Pour inspirer l'amour

17. Charmes: IV. Pour les guerisons

18. Charmes: V. Pour evoquer l'image du passe

19. Charmes: VI. Pour appeler la joie

20. Scenes d'enfants: I. Cris dans la rue

21. Scenes d'enfants: II. Jeux sur la plage

22. Scenes d'enfants: III. Jeu II

23. Scenes d'enfants: IV. Jeu III

24. Scenes d'enfants: V. Jeunes filles au jardin

Although Adolfo Salazar praised the "agreeable colouring" resulting from the "experiments on the keyboard" of Frederic Mompou, the great Madrid critic saw something suspicious in this Catalan composer he had turned his back on everything which appeared to be truly essential to the mainstream of great European music, and what defines great creators and able craftsmen alike, Neither counterpoint, fugue, orchestration, or thematic and formal development appear to have ever held the least interest for the composer of Cancons i Danses. But is this a criterion for judging the work of a composer who adopts an aesthetic position based precisely on the apparent renunciation of those values? Mompou did not want to compose like Cesar Franck, - even less like Schoenberg, and if his lack of ambition was no obstacle to his becoming a composer of some merit, it is because of the perfect marriage between his means and his ends. Salazar's criticism reminds us of the judgement of Rene Leibowitz concerning Chopin: the Polish composer would always be in reality just an amateur composer (albeit an amateur of genius). In both cases, it is understandable that thinkers of such rigidly held (though sometimes misguided) views should harbour such suspicions. In both instances, although on a different scale, it is how the music affects us, and not some opposing theory, which silences any verdict reached.

The career of Frederic Mompou, born in Barcelona in 1893, was typical of composers of his generation, but he clearly stands out from the others for his originality. His mother's family, of French origin and owners of the Dencausse bell foundry, was to have a decisive importance in the sentimental education of the composer. His attraction for French culture, a preference more Manichean than passionate; he once proclaimed French music as true and German music as false, is shared by nearly all his Catalan contemporaries, except Roberto Gerhard, but his direct knowledge of the fascinating sound world of bells was a much more personal characteristic which was to give him the unmistakable colouring of his most beautiful chords. Hearing Faure performing his own music in Barcelona was one of the great influences on his life, and the advanced level he was reaching as a pianist made his dream to go to Paris to study in the Conservatoire, directed at that time by Faure himself, perfectly feasible, but his almost pathological shyness prevented him from even applying for admission. Instead, he took private lessons from the great pianist Ferdinand Motte-Lacroix. Mompou therefore never followed any conventional studies of counterpoint, fugue and composition. The peculiarities of his character were also soon to bar the way to the possibility of a career as a concert pianist. For ever shut in in his own aesthetic world, but also arousing growing admiration in Motte-Lacroix and other French musicians, Mompou composed and began to find success by performing his works in the most exclusive Parisian salons. His success was confirmed by the appearance in 1921 of a famous article by the influential critic Emile Vuillermoz, defender in France of the causes not only of Debussy and Ravel, but also of Schoenberg and Stravinsky. The authority of Vuillermoz makes his final judgement all the more impressive. "The only disciple and successor to the composer of La Mer (… ) is surely the young Spaniard Frederic Mompou, who, without ever having known Debussy, has understood and absorbed the essence of his teaching."

Vuillermoz's text, a remarkable mixture of analytic precision and literary quality quite uncommon in writing of this kind, represents a practically definitive description of Mompou's style and artistic personality. His return to Barcelona, where he was to remain for the rest of his life in some isolation and with periods of total silence, was not to bring any significant changes in his musical language, He was to become a rather patriarchal figure, somewhat remote, even alien, to the young Catalan composers who tried to assimilate, perhaps with more failure than success, the styles of the European vanguard. Mompou had a characteristic beyond their reach: that of being a composer performed and listened to spontaneously by the highly conservative public of his country. His works even featured in the syllabuses of the Barcelona Conservatory (and still do), and are played by an endless number of students. Whether the criticism of his lack of interest in the new musical styles is legitimate or not, nobody can deny Mompou's qualities which define him as a genuine artist in the highest sense of this word: the possession of a personal poetry, his own unmistakeable sound, discovered through direct contact with the sound of the piano, and the way in which he found in this an expression of his inner world, formed from a mixture of such disparate elements as great Catalan mystical poetry and love of the atmosphere of the maritime quarters which he knew in the Barcelona of his childhood, in which the advance of civilization is imposed on the continuance of a pre-capitalist life, and where the relationship of the individual with traditional music could still be immediate. In fact he gave the name Barri de platja (beach quarter) to the chord G flat, C, E flat, A flat, D, which, for him, was the essence of all his music. In its sonority it surely tries to reproduce the sound of the familiar bells and the distant cries of the seagulls, mixing with those of the children playing near the onlooker, who, although alone, lovingly contemplates the colourful scene of the people by the sea and finds in it something of deep significance.

It is this love for popular Catalan culture that makes Mompou's Cancons i Danses (Songs and Dances) one of his most important works. At least they are, of all his creations, the best-known in his own country, and the fact that their composition spreads over nearly the whole of his life, from 1918 to 1962, makes them all the more interesting. The pairing of a slow song followed by a more animated dance reminds one of the combination of prelude and fugue, or dances such as the Hungarian Csardas. The thirteen pieces written for piano, almost the only instrument Mompou composed for (Canco i Dansa No. 13 also exists for guitar, and No.15 for organ) on the whole represent adaptations of popular Catalan songs. If setting traditional tunes to harmony is very common amongst composers of his time, Mompou shines in this art: his ability to give a song a harmony which appears simple and natural, but at the same time original and highly sophisticated, is one of his greatest secrets. The chords may be common, but often sweet and sonorous dissonances colour them, frequently in the form of an added upper melody with an unpredictable line which appears to emerge from the very excitation of the resonance of the natural harmonics, a technique which constitutes the true counterpoint of Mompou. Amongst the songs used are La Filla del Carmesi, and Dansa de Castelltercol (Canco i Dansa No. I), Senyora Isabel i Galop de Cortesia (No.2), El Noi de la Mare (Canco No.3), El Mariner i Ball del Ciri (Canco i Dansa No.4), Muntanyes Regalades and L 'Hereu Riera (No, 7), El Testament d'Amelia and La Filadora (No.8), El Rossinuyol (Canco No.9), Ball de l'Aliga i Turcs I cavallets, both of which come from the dances of the fiestas of the Patum de Berga (Canco i Dansa No. 11), La Dama d'Arag6 and La Mala Nova (No. 12) and Canco del Lladre (Canco No. 14). But not all these pieces are based on the rich universe of Catalan song. The Canco i Dansa No. 10, showing other less well-known concerns of Mompou, uses two Cantigas of Alfonso x. The rest are of original inspiration. If the sounds of his homeland are omnipresent (Dansa No.5 could easily be taken for another popular song, while Dansa No.3 is a sardana, the most characteristic dance of Catalonia, known to be salvaged from an unfinished string quartet, and Dansa No.9 almost quotes popular themes as in Dansa No. 14), in other cases the stylistic references are broader: Canco No.5, conceived during a dream, sounds like an ancient chant, full of austere solemnity and Canco i Dansa No.6 use West Indian rhythms, which also greatly influenced Xavier Montsalvatge, a Barcelona composer of a somewhat younger generation than Mompou.

Although Mompou is perhaps best-known for his adaptation of popular songs, the Catalan composer often had more abstract conceptions, in which he wanted to reflect his own particular interest in the transcendence reflected in mystic poetry or related texts. Although Mompou originally gave the title Karmas to a group of six pieces composed between 1920 and 1921, on realising that the Indian word did not exactly mean what he had imagined, he changed it for Charmes, in the sense of enchantment, a trance-like state caused by a spell. The French titles owe a debt to those which Debussy gave to his Preludes or Etudes … pour endormir la souffrance, pour penetrer les ames, pour inspirer l 'amour, pour les guerissons, pour evoquer l'image du passe, pour appeler la joie. In almost all the pieces an initial harmonic situation is held with small variations which do not give it a discursive sense, but manage to keep the listener in a hypnotic state, in which time seems to stand still. In the first of the Charmes (To Ease Suffering) an ostinato acompaniment is gradually modified until it appears in the most serious register of the piano, and establishing a framework of austere dissonance above which is repeated almost without variation a short melodic fragment. The second (To Penetrate Souls) features a slow melody of only five notes which are repeated in many different ways without losing their character of growing intensity, culminating in the dissonance of the fourth note, the most intense dissonace of all. In the third piece (To Inspire Love) an energetic ascending theme, harmonically almost identical to the Barri de Platja chord, serves as a backdrop for a slow recitative. A second section introduces a cheerful ostinato above which a cantilena of very sharp notes is developed. The dissolving of the ostinato prepares for the recapitulation of the first part. The fourth Charme (For Healing) is made up of a melody in dotted rhythm appearing above two different ostinati with the muffled beat of a chord without melody. The fifth (To Evoke Images of the Past) is divided into two parts: in the first, undulating arpeggios appearing to imitate the natural resonances of the harmonics sustain a prolonged melody; in the second, a new, progressively changing ostinato introduces first a new melody, then recalls that of the first part. The last of The Charmes (To Invoke Joy) matches its title with a leaping, unaccompanied melody leading to an animated dance, not far removed from any of those which feature in the Cancons i Danses. The piece ends with a return to the first melody, now against a background of chords.

During Mompou's successful years in Paris one of the works which most captivated his public was the one which carried the Schumann-like title Scenes d'enfants (Scenes of childhood). In fact it consists of the Three Jeux (games) he composed in 1915, to which he added the opening piece Cris dans la rue (Cries in the Street), and, as an ending, the well-known Jeunes filles au jardin (Girls in the Garden). The two movements which serve as a framework use the Catalan song La Filla del Marxant, which gives the work a cyclical character, in the form of an arc which opens and closes. Cris dans la rue depicts wild games based on a children's tune harmonized with rich overlays of fourths and fifths. A second melody leads to the first version of La Filla del Marxant, which is replaced by the initial chatter which appears to fade into the distance. The first of The Three Jeux, entitled Jeux sur la Plage (Games on the Beach) begins and ends with what could be the cries of birds or children running around on the seashore. The main body of the piece is dedicated to a children’s' song which recurs in a circular way with a rocking rhythm. The second Jeu begins and ends with distant cries. This time the song's rhythm becomes rather passionate, while in the third Jeu, identical in structure to those which preceded it, it gathers strength until it reaches a high pitch of emotional intensity. The sadness which floats between the games (perhaps that of the observer who can no longer participate in them) permeates the beginning of Jeunes Filles au Jardin in which ring out some of the most fascinating cries of the many which the work contains. A prolonged melody, full of a sweet serenity, is cut off by the return of the initial cries, which lead on to the new version of La Filla del Marxant. The repetition of the opening passage marks the end of Scenes d’enfants, one of the most frequently performed of all the works of this fascinating composer.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads