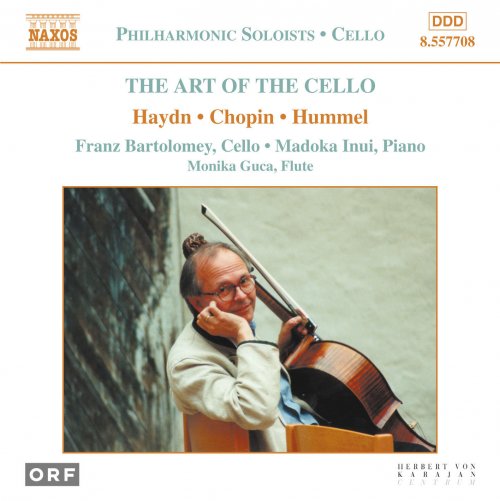

Franz Bartolomey, Monika Guca, Madoka Inui - The Art of the Cello (2005)

BAND/ARTIST: Franz Bartolomey, Monika Guca, Madoka Inui

- Title: The Art of the Cello

- Year Of Release: 2005

- Label: Naxos

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:09:46

- Total Size: 264 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Grand Sonata in A Major for Cello and Piano, Op. 104: I. Allegro amabile e grazioso

02. Grand Sonata in A Major for Cello and Piano, Op. 104: II. Romanza: Un poco adagio e con espressione

03. Grand Sonata in A Major for Cello and Piano, Op. 104: III. Rondo: Allegro, un poco vivace

04. Trio in G Major for Flute, Cello and Piano, Hob. XV:15: I. Allegro

05. Trio in G Major for Flute, Cello, and Piano, Hob. XV:15: II. Andante

06. Trio in G Major for Flute, Cello, and Piano, Hob. XV:15

07. Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 65: I. Allegro moderato

08. Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 65: II. Scherzo: Allegro con brio

09. Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 65: III. Largo

10. Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 65: III. Finale: Allegro

The violoncello, meaning, in Italian, a small violone, is generally known by the shorter name of ‘cello’, and is a string instrument an octave lower than the viola, its four strings tuned C-G-d-a. Its structure and form correspond to those of the violin, but the neck is relatively shorter and the sides deeper. The bow is somewhat shorter, but stronger than that used for the violin.

As the violin may correspond to the discant, and the viola to the tenor, so the cello was originally identical with the bass of the old viola da braccio family. It had a longer struggle than its two sisters to free itself from the gamba family. In 1740 there appeared in Amsterdam a treatise by Hubert Leblanc, a lawyer and music-lover from France, that throws a characteristic light on the importance of the violoncello in that time. The work is a vigorous defence of the viola da gamba against the violoncello that was slowly encroaching on the former’s territory. This was in fact a completely unintelligible polemic, since at the time there was little literature on the younger instrument that was worth talking about. This was first changed by the Duport brothers, who ranked as the most important champions of the new school of cello-playing both in duo sonatas, such as those of Beethoven, and in chamber music, as, for example, the classical string quartet and quintet.

It was about 1710 that the violoncello acquired its classical dimensions through the Italian violin-maker Antonio Stradivari (1644 or 1648/9-1737), with a body length of 75-76 and a depth of 11.5 centimetres. After that there were many other cellos built, as well as gambas, and until about 1800 instruments of a mixed form from both types, among other things with the change of a straight neck into a neck at an angle. The use of the spike first became customary in about 1860.

The greatest masters of violin-making, such as Amati, Guarneri and Stradivari, also started to make cellos. Montagnana, Grancino, Testore and Tecchler specialised almost exclusively in the instrument.

My instrument, on which I play in the present recording, was made by David Tecchler (1666-after 1743) in Rome in 1727. A master-craftsman from Salzburg, he first went to Venice, where he experienced some hostility, moving in 1705 to Rome where he reached the height of his profession, considered the most important maker there. His splendidly made instruments are marked by their great fullness of tone. He generally preferred very large models, using special wood and a yellow-red varnish. A characteristic is the lengthening of the corners and the particularly wide F holes.

While the gamba remained the instrument of soloists, the cello, then generally with five or six strings, was reduced to strengthening the continuo in the orchestra and in chamber music.

From the end of the seventeenth century Italy took the lead in compositions for the cello. In 1689 Domenico Gabrielli wrote a Ricercar for the cello and laid the foundation for the independent solo literature of the instrument. In the first half of the eighteenth century Vivaldi and Tartini, among others, and, with some virtuosity, Boccherini, wrote sonatas for the cello. The instrument acquired new importance in the transition to the classical period through composers such as Carl Stamitz, Luigi Boccherini, Georg Matthias Monn, and particularly Joseph Haydn, who wrote solo concertos for the cello.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the cantabile playing of the cello acquired growing importance. Generations of romantic composers made use of the particular feeling of which the cello was capable, giving expression to melodic sonority and melancholy resignation. In the chamber music of Beethoven, Brahms, Fauré, Grieg, Rachmaninov, Debussy, and others, cellists could explore the whole range of musical feeling. There were wonderful concertos by Schumann, Dvořák, Saint-Saëns, Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky (Rococo Variations), Brahms (Double Concerto), and Elgar, and works in which the cello had a concertante rôle by Richard Strauss (Don Quixote) and Hindemith.

For me the cello has a particularly fascinating and important place in opera. There it embodies the direct expression of the human soul in music. With its range it has an almost physical affinity with the human and responds directly to it. It is the instrument that can express the deepest feelings of love and death.

Unique in all opera is the cello solo in Die Frau ohne Schatten by Richard Strauss, my favourite solo: the curtain falls, while the scene is changed, and the cello, free of stage action, becomes the protagonist.

King Philip sings in the great aria from Verdi’s Don Carlo in dialogue with the cello of his isolation and erotic desires; the cello first sinks down, then rises a little, allows a glimmer of hope to be heard, and finally despairs. The music expresses resignation and the cello supports the singer’s feelings.

The duet of Othello and Desdemona at the end of the first act of Verdi’s Otello is accompanied by a cello solo, then joined by the whole cello section; the world of the two lovers is still as it should be, yet Othello conjures away the revenge of Fate on the outsider, too fortunate in his love.

At the beginning of the first act of Wagner’s Die Walküre Siegmund and Sieglinde do not know that they are twins. The eyes of the two outcasts meet and they experience happiness for the first and last time. Here too an almost recitative-like cello solo supports the intimacy of the situation.

Agathe’s aria from Weber’s Der Freischütz is accompanied by a pure and romantic cello that reveals to us the unfulfilled love, hope and confidence that the power of evil will not triumph and love will not always remain unfulfilled.

When Cavaradossi, in Puccini’s Tosca, is about to die, the cello and the clarinet, operatic instruments that express despair, accompany him on his last way. A descending chromatic scale shows where his path is leading.

Continuo playing is a fascinating element in opera. Working on recitatives in Mozart’s operas with Nikolaus Harnoncourt, a conductor with whom collaboration was among my most decisive artistic encounters, opened a completely new dimension of musical expression. The specific dramatic situations that drive the plot forward are found in the recitatives. Each individual note has its importance, with notes that are violent, pointed, loud, gentle, particularly beautifully played, slow, fast or without vibrato. As a continuo player one is a part of the musical dramatic situation.

01. Grand Sonata in A Major for Cello and Piano, Op. 104: I. Allegro amabile e grazioso

02. Grand Sonata in A Major for Cello and Piano, Op. 104: II. Romanza: Un poco adagio e con espressione

03. Grand Sonata in A Major for Cello and Piano, Op. 104: III. Rondo: Allegro, un poco vivace

04. Trio in G Major for Flute, Cello and Piano, Hob. XV:15: I. Allegro

05. Trio in G Major for Flute, Cello, and Piano, Hob. XV:15: II. Andante

06. Trio in G Major for Flute, Cello, and Piano, Hob. XV:15

07. Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 65: I. Allegro moderato

08. Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 65: II. Scherzo: Allegro con brio

09. Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 65: III. Largo

10. Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 65: III. Finale: Allegro

The violoncello, meaning, in Italian, a small violone, is generally known by the shorter name of ‘cello’, and is a string instrument an octave lower than the viola, its four strings tuned C-G-d-a. Its structure and form correspond to those of the violin, but the neck is relatively shorter and the sides deeper. The bow is somewhat shorter, but stronger than that used for the violin.

As the violin may correspond to the discant, and the viola to the tenor, so the cello was originally identical with the bass of the old viola da braccio family. It had a longer struggle than its two sisters to free itself from the gamba family. In 1740 there appeared in Amsterdam a treatise by Hubert Leblanc, a lawyer and music-lover from France, that throws a characteristic light on the importance of the violoncello in that time. The work is a vigorous defence of the viola da gamba against the violoncello that was slowly encroaching on the former’s territory. This was in fact a completely unintelligible polemic, since at the time there was little literature on the younger instrument that was worth talking about. This was first changed by the Duport brothers, who ranked as the most important champions of the new school of cello-playing both in duo sonatas, such as those of Beethoven, and in chamber music, as, for example, the classical string quartet and quintet.

It was about 1710 that the violoncello acquired its classical dimensions through the Italian violin-maker Antonio Stradivari (1644 or 1648/9-1737), with a body length of 75-76 and a depth of 11.5 centimetres. After that there were many other cellos built, as well as gambas, and until about 1800 instruments of a mixed form from both types, among other things with the change of a straight neck into a neck at an angle. The use of the spike first became customary in about 1860.

The greatest masters of violin-making, such as Amati, Guarneri and Stradivari, also started to make cellos. Montagnana, Grancino, Testore and Tecchler specialised almost exclusively in the instrument.

My instrument, on which I play in the present recording, was made by David Tecchler (1666-after 1743) in Rome in 1727. A master-craftsman from Salzburg, he first went to Venice, where he experienced some hostility, moving in 1705 to Rome where he reached the height of his profession, considered the most important maker there. His splendidly made instruments are marked by their great fullness of tone. He generally preferred very large models, using special wood and a yellow-red varnish. A characteristic is the lengthening of the corners and the particularly wide F holes.

While the gamba remained the instrument of soloists, the cello, then generally with five or six strings, was reduced to strengthening the continuo in the orchestra and in chamber music.

From the end of the seventeenth century Italy took the lead in compositions for the cello. In 1689 Domenico Gabrielli wrote a Ricercar for the cello and laid the foundation for the independent solo literature of the instrument. In the first half of the eighteenth century Vivaldi and Tartini, among others, and, with some virtuosity, Boccherini, wrote sonatas for the cello. The instrument acquired new importance in the transition to the classical period through composers such as Carl Stamitz, Luigi Boccherini, Georg Matthias Monn, and particularly Joseph Haydn, who wrote solo concertos for the cello.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the cantabile playing of the cello acquired growing importance. Generations of romantic composers made use of the particular feeling of which the cello was capable, giving expression to melodic sonority and melancholy resignation. In the chamber music of Beethoven, Brahms, Fauré, Grieg, Rachmaninov, Debussy, and others, cellists could explore the whole range of musical feeling. There were wonderful concertos by Schumann, Dvořák, Saint-Saëns, Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky (Rococo Variations), Brahms (Double Concerto), and Elgar, and works in which the cello had a concertante rôle by Richard Strauss (Don Quixote) and Hindemith.

For me the cello has a particularly fascinating and important place in opera. There it embodies the direct expression of the human soul in music. With its range it has an almost physical affinity with the human and responds directly to it. It is the instrument that can express the deepest feelings of love and death.

Unique in all opera is the cello solo in Die Frau ohne Schatten by Richard Strauss, my favourite solo: the curtain falls, while the scene is changed, and the cello, free of stage action, becomes the protagonist.

King Philip sings in the great aria from Verdi’s Don Carlo in dialogue with the cello of his isolation and erotic desires; the cello first sinks down, then rises a little, allows a glimmer of hope to be heard, and finally despairs. The music expresses resignation and the cello supports the singer’s feelings.

The duet of Othello and Desdemona at the end of the first act of Verdi’s Otello is accompanied by a cello solo, then joined by the whole cello section; the world of the two lovers is still as it should be, yet Othello conjures away the revenge of Fate on the outsider, too fortunate in his love.

At the beginning of the first act of Wagner’s Die Walküre Siegmund and Sieglinde do not know that they are twins. The eyes of the two outcasts meet and they experience happiness for the first and last time. Here too an almost recitative-like cello solo supports the intimacy of the situation.

Agathe’s aria from Weber’s Der Freischütz is accompanied by a pure and romantic cello that reveals to us the unfulfilled love, hope and confidence that the power of evil will not triumph and love will not always remain unfulfilled.

When Cavaradossi, in Puccini’s Tosca, is about to die, the cello and the clarinet, operatic instruments that express despair, accompany him on his last way. A descending chromatic scale shows where his path is leading.

Continuo playing is a fascinating element in opera. Working on recitatives in Mozart’s operas with Nikolaus Harnoncourt, a conductor with whom collaboration was among my most decisive artistic encounters, opened a completely new dimension of musical expression. The specific dramatic situations that drive the plot forward are found in the recitatives. Each individual note has its importance, with notes that are violent, pointed, loud, gentle, particularly beautifully played, slow, fast or without vibrato. As a continuo player one is a part of the musical dramatic situation.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads