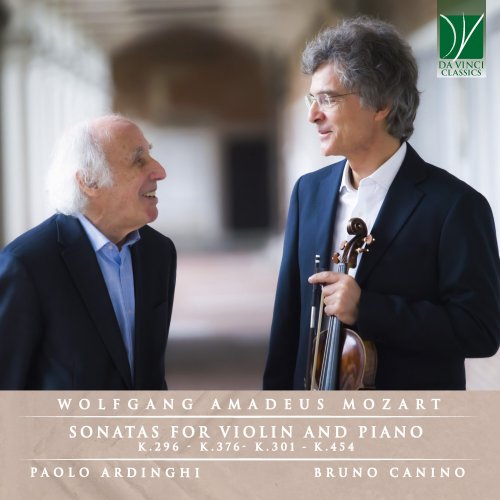

Paolo Ardinghi, Bruno Canino - Mozart: Sonatas for Violin and Piano, K.296, K.301, K.376, K.454 (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Paolo Ardinghi, Bruno Canino

- Title: Mozart: Sonatas for Violin and Piano, K.296, K.301, K.376, K.454

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:10:49

- Total Size: 342 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Violin Sonata in C Major, K. 296: I. Allegro vivace

02. Violin Sonata in C Major, K. 296: II. Andante sostenuto

03. Violin Sonata in C Major, K. 296: III. Rondeau. Allegro

04. Violin Sonata in G Major, K. 301: I. Allegro con spirito

05. Violin Sonata in G Major, K. 301: II. Allegro

06. Violin Sonata in F Major, K. 376: I. Allegro

07. Violin Sonata in F Major, K. 376: II. Andante

08. Violin Sonata in F Major, K. 376: III. Rondeau. Allegretto grazioso

09. Violin Sonata in B-Flat Major, K. 454: I. Largo.Allegro

10. Violin Sonata in B-Flat Major, K. 454: II. Andante

11. Violin Sonata in B-Flat Major, K. 454: III. Allegretto

Nowadays, it is rather uncommon for a virtuoso performer to achieve an equal degree of proficiency in the performance of two different instruments, particularly if these belong to two entirely different families, such as that of bowed string instruments and keyboard. A few cases exist, but it is very unusual for a soloist of international standing to master equally well two or more instruments. Even rarer is the case of somebody who, besides being a skilled multi-instrumentalist, is also an expert composer, let alone a composer of genius. Of course, the category of musical “normality” is hardly appliable to Mozart, whose talent was one of the most impressive in the whole of music history. Indeed, he played perfectly at least four instruments (the keyboard – implying both harpsichord and his favourite fortepiano –, the organ, the violin, and the viola) and earned his living, at various times in his life, as a professional performer of both the violin and the piano. Arguably, he felt more at home with the keyboard than with the violin, but this may be due more to psychological than to exquisitely musical reasons. The violin was his father’s instrument; Leopold was one of the most appreciated violinists of his time, and had authored a ground-breaking treatise of violin playing in the very same year when Wolfgang was born, i.e. 1756. That treatise enjoyed unparalleled success at the time, and is still a reference work for understanding the performing practices of the era. In a famous family portrait representing the Mozarts, Leopold is pictured playing the violin in a rather leisurely fashion, Wolfgang is at the keyboard, and Nannerl (slightly incongruously) sings. (In fact, Nannerl was an excellent pianist herself, but her vocal gifts were not particularly remarkable). In that portrait, Leopold’s wife seems to look upon her family from a portrait hanging from the wall, since she had sadly died during an unfortunate tour to Paris with her son.

Still, Mozart’s absolute expertise as a violin and keyboard player was a guarantee for the quality of his output written for the two instruments together. The intimate knowledge of an instrument’s performing technique and expressive resources which one obtains by professionally playing it is immediately apparent. Thus, it comes as no wonder that a musician whose first compositions date back to his early childhood wrote his first Sonatas for violin and keyboard duo at the green age of seven. While doubtlessly charming and impressively conceived, however, these childhood Sonatas rely mainly on the established model of the era (and it would be hard to imagine a boy of seven revolutionising a musical genre!). In fact, many Sonatas written for this ensemble (as those written for flute and piano) were conceived primarily as piano works with accompaniment of a melodic instrument. This may puzzle today’s readers, since (inaccurately) many violin sonatas are currently being offered on concert programmes as… “violin” sonatas with piano “accompaniment”. While it is highly unfair to label the piano part of a Brahms sonata as an accompaniment to the violin part, the heritage of a conception of violin virtuosity as a soloist’s exhibition at times impinges on the concept of chamber music. Still, this may simply be the violin’s revenge, since its part had been thought of as expendable in many eighteenth-century models. The violin doubled the keyboard part, or added charming but unmeaningful ornaments to a part which could easily stand by itself.

Gradually, this concept evolved, and the merit for transforming a soloist’s soliloquy with optional doubling into a real dialogue of peers is largely ascribable precisely to Mozart’s later compositions in this genre.

In 1777, Mozart was 21 years old. He was a young man who hardly suffered the atmosphere of the Salzburg court, and the duties of his job as a concertmaster in the Archbishop’s orchestra. He quarrelled with his employer, Colloredo, and was dismissed – along with his father, who probably did not take very well his son’s outbursts. In fact, Leopold managed to retrieve his post (and probably Colloredo was rather keen to welcome him back, since violinists of Leopold’s standing were not found everywhere). Wolfgang, instead, left with his mother in search for a new job. The most obvious place where one could look for a vacancy was Mannheim, with its legendary orchestra. There, Mozart came to know the latest fashion in terms of musical composition, as he wrote to his father in Salzburg: “I send my sister herewith six duets for clavicembalo [keyboard] and violin by Schuster, which I have often played here. They are not bad. If I stay on, I shall write six myself in the same style, as they are very popular”.

Mozart had a perfect intuition for what could please the audience, though he miraculously managed, in most cases, to combine that need with his own artistic drives, without merely adapting himself to the listeners’ tastes. So, his own published collection of six Sonatas was clearly conceived with Schuster’s successful model in mind, but also with a quintessentially Mozartean independence of mind and creative power. He actually wrote seven Sonatas, but, since publications were normally done by groups of six, he left one out when issuing in printing what was labelled as his “op. 1”, which appeared in in Paris in 1778. He dedicated his work to the Electress of the Palatinate, the wife of Karl Theodor, the Prince-Elector, and therefore the collection is frequently referred to as the “Palatine Sonatas”.

The first Sonata recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album is the one he left out from the Parisian publication, i.e. KV 296. It would be published three years later, in 1781, along with other five works in Vienna. KV 296 had been conceived for a young amateur piano player, and in fact its technical demands are far from extreme. In spite of this, the opening movement is very brilliant, with pronounced dynamic contrasts and a buffo-opera style. The lyrical second movement, in F major, seems at first to bow to the earlier convention of a protagonist keyboard and a subservient violin; however, in the central section the broad expressive leaps are entrusted to the violin, which later is required to perform the reprise of the opening section with its singing quality. The jaunty Rondeau is built on a chatty accompaniment of quavers (played at first by the violin, and then by the piano), and its refrain is a broad, cheerful melody alternatively performed by the two instruments. Here, their equality is apparent, and the melodic fragments are divided practically equally between the two partners.

This Sonata was left out from the Parisian publication of 1778 possibly because it was too ahead of its time, for instance in its three-movement structure. Most of those published in 1778, in fact, correspond to the early-eighteenth-century model consisting of two rather short movements, as happens with KV 301. In spite of this, however, the violin’s standing is clearly affirmed in the first movement, and under this viewpoint Mozart did not limit himself to the déjà vu but rather purposefully intervened on the very structure of the genre. The second and last movement is reminiscent of Italian opera (as happens with so many of Mozart’s works), also as concerns the metrical structure of the themes. The shape of the melodies is in fact determined by patterns which closely correspond to those of the Italian poetry of comic opera.

Sonata KV 376 belongs in the second series of six violin sonatas, published as “op. 2” in Vienna. As said before, KV 296 was also included in this set, along with newly composed works. The publication stood out for its originality and freshness of invention, as was noted by a reviewer writing a couple of years later on a musical review in Hamburg. “These sonatas are the only ones of their kind. They are rich in new ideas, showing traces of the great musical genius of their author…. Moreover, the violin accompaniment is so ingeniously combined with the piano part that both instruments are continuously employed; and thus these sonatas demand a violinist as accomplished as the pianist”. In fact, these works were conceived also as a showcase for their composer’s talent, both in writing and in performing music; and they certainly did not fail this task. In the first movement, the most interesting aspects are found in the development, which includes new, original elements and an attention for contrapuntal textures which is indeed very forward-looking.

The lyrical vein typical for Mozart, and particularly for his enchanted vocal themes, finds a beautiful outlet in the sweet second movement, featuring also a tight dialogue and interchange between the two instruments. The seemingly martial character of the third movement is far from belligerent. Rather, it is influenced, once more, by the metrical schemes of vocal music, where the march rhythm was frequently employed for the musical setting of some particular Italian metrical patterns.

The CD closes with one of the best-known examples of Mozart’s violin music. In this case, it is rather appropriate to speak of a “Violin” Sonata, since the violin’s part is highly concertante, very demanding and with a truly soloistic inspiration, in spite of the composer’s careful attention to the chamber music style of the work. This piece had been conceived on the occasion of the arrival in Vienna of a famous Italian violinist, Regina Strinasacchi, who was famous for the beauty of her tone and of her cantabile. Mozart clearly did his best in order to put his musical partner’s gifts into relief, and created a majestic, solemn, and touching piece, which is one of the favourites by violin players. Legend has it that Mozart was in such rush before the concert (where he played with Strinasacchi) that he had no time for writing down his own part. Since, at the time, playing by memory was not considered “professional”, he put a blank sheet of paper on the music stand. Whilst this last part of the anecdote is likely to be apocryphal (just as the fact that the Emperor noticed the blank sheet and asked for explanations), it is probable that Mozart did play from an unfinished manuscript, as is revealed by close inspection of the handwritten autograph. This does not prevent this Sonata from being an absolute masterpiece in the repertoire for violin and piano, and a cornerstone in the evolution of the genre.

Together, these Sonatas allow us to observe the evolution of Mozart’s thought on this genre, in spite of the relatively little time dividing them. Mozart’s genius was always in quest for novel ideas, and this, in turn, brought numerous coeval genres to their maturity thanks to Mozart’s unique contributions.

01. Violin Sonata in C Major, K. 296: I. Allegro vivace

02. Violin Sonata in C Major, K. 296: II. Andante sostenuto

03. Violin Sonata in C Major, K. 296: III. Rondeau. Allegro

04. Violin Sonata in G Major, K. 301: I. Allegro con spirito

05. Violin Sonata in G Major, K. 301: II. Allegro

06. Violin Sonata in F Major, K. 376: I. Allegro

07. Violin Sonata in F Major, K. 376: II. Andante

08. Violin Sonata in F Major, K. 376: III. Rondeau. Allegretto grazioso

09. Violin Sonata in B-Flat Major, K. 454: I. Largo.Allegro

10. Violin Sonata in B-Flat Major, K. 454: II. Andante

11. Violin Sonata in B-Flat Major, K. 454: III. Allegretto

Nowadays, it is rather uncommon for a virtuoso performer to achieve an equal degree of proficiency in the performance of two different instruments, particularly if these belong to two entirely different families, such as that of bowed string instruments and keyboard. A few cases exist, but it is very unusual for a soloist of international standing to master equally well two or more instruments. Even rarer is the case of somebody who, besides being a skilled multi-instrumentalist, is also an expert composer, let alone a composer of genius. Of course, the category of musical “normality” is hardly appliable to Mozart, whose talent was one of the most impressive in the whole of music history. Indeed, he played perfectly at least four instruments (the keyboard – implying both harpsichord and his favourite fortepiano –, the organ, the violin, and the viola) and earned his living, at various times in his life, as a professional performer of both the violin and the piano. Arguably, he felt more at home with the keyboard than with the violin, but this may be due more to psychological than to exquisitely musical reasons. The violin was his father’s instrument; Leopold was one of the most appreciated violinists of his time, and had authored a ground-breaking treatise of violin playing in the very same year when Wolfgang was born, i.e. 1756. That treatise enjoyed unparalleled success at the time, and is still a reference work for understanding the performing practices of the era. In a famous family portrait representing the Mozarts, Leopold is pictured playing the violin in a rather leisurely fashion, Wolfgang is at the keyboard, and Nannerl (slightly incongruously) sings. (In fact, Nannerl was an excellent pianist herself, but her vocal gifts were not particularly remarkable). In that portrait, Leopold’s wife seems to look upon her family from a portrait hanging from the wall, since she had sadly died during an unfortunate tour to Paris with her son.

Still, Mozart’s absolute expertise as a violin and keyboard player was a guarantee for the quality of his output written for the two instruments together. The intimate knowledge of an instrument’s performing technique and expressive resources which one obtains by professionally playing it is immediately apparent. Thus, it comes as no wonder that a musician whose first compositions date back to his early childhood wrote his first Sonatas for violin and keyboard duo at the green age of seven. While doubtlessly charming and impressively conceived, however, these childhood Sonatas rely mainly on the established model of the era (and it would be hard to imagine a boy of seven revolutionising a musical genre!). In fact, many Sonatas written for this ensemble (as those written for flute and piano) were conceived primarily as piano works with accompaniment of a melodic instrument. This may puzzle today’s readers, since (inaccurately) many violin sonatas are currently being offered on concert programmes as… “violin” sonatas with piano “accompaniment”. While it is highly unfair to label the piano part of a Brahms sonata as an accompaniment to the violin part, the heritage of a conception of violin virtuosity as a soloist’s exhibition at times impinges on the concept of chamber music. Still, this may simply be the violin’s revenge, since its part had been thought of as expendable in many eighteenth-century models. The violin doubled the keyboard part, or added charming but unmeaningful ornaments to a part which could easily stand by itself.

Gradually, this concept evolved, and the merit for transforming a soloist’s soliloquy with optional doubling into a real dialogue of peers is largely ascribable precisely to Mozart’s later compositions in this genre.

In 1777, Mozart was 21 years old. He was a young man who hardly suffered the atmosphere of the Salzburg court, and the duties of his job as a concertmaster in the Archbishop’s orchestra. He quarrelled with his employer, Colloredo, and was dismissed – along with his father, who probably did not take very well his son’s outbursts. In fact, Leopold managed to retrieve his post (and probably Colloredo was rather keen to welcome him back, since violinists of Leopold’s standing were not found everywhere). Wolfgang, instead, left with his mother in search for a new job. The most obvious place where one could look for a vacancy was Mannheim, with its legendary orchestra. There, Mozart came to know the latest fashion in terms of musical composition, as he wrote to his father in Salzburg: “I send my sister herewith six duets for clavicembalo [keyboard] and violin by Schuster, which I have often played here. They are not bad. If I stay on, I shall write six myself in the same style, as they are very popular”.

Mozart had a perfect intuition for what could please the audience, though he miraculously managed, in most cases, to combine that need with his own artistic drives, without merely adapting himself to the listeners’ tastes. So, his own published collection of six Sonatas was clearly conceived with Schuster’s successful model in mind, but also with a quintessentially Mozartean independence of mind and creative power. He actually wrote seven Sonatas, but, since publications were normally done by groups of six, he left one out when issuing in printing what was labelled as his “op. 1”, which appeared in in Paris in 1778. He dedicated his work to the Electress of the Palatinate, the wife of Karl Theodor, the Prince-Elector, and therefore the collection is frequently referred to as the “Palatine Sonatas”.

The first Sonata recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album is the one he left out from the Parisian publication, i.e. KV 296. It would be published three years later, in 1781, along with other five works in Vienna. KV 296 had been conceived for a young amateur piano player, and in fact its technical demands are far from extreme. In spite of this, the opening movement is very brilliant, with pronounced dynamic contrasts and a buffo-opera style. The lyrical second movement, in F major, seems at first to bow to the earlier convention of a protagonist keyboard and a subservient violin; however, in the central section the broad expressive leaps are entrusted to the violin, which later is required to perform the reprise of the opening section with its singing quality. The jaunty Rondeau is built on a chatty accompaniment of quavers (played at first by the violin, and then by the piano), and its refrain is a broad, cheerful melody alternatively performed by the two instruments. Here, their equality is apparent, and the melodic fragments are divided practically equally between the two partners.

This Sonata was left out from the Parisian publication of 1778 possibly because it was too ahead of its time, for instance in its three-movement structure. Most of those published in 1778, in fact, correspond to the early-eighteenth-century model consisting of two rather short movements, as happens with KV 301. In spite of this, however, the violin’s standing is clearly affirmed in the first movement, and under this viewpoint Mozart did not limit himself to the déjà vu but rather purposefully intervened on the very structure of the genre. The second and last movement is reminiscent of Italian opera (as happens with so many of Mozart’s works), also as concerns the metrical structure of the themes. The shape of the melodies is in fact determined by patterns which closely correspond to those of the Italian poetry of comic opera.

Sonata KV 376 belongs in the second series of six violin sonatas, published as “op. 2” in Vienna. As said before, KV 296 was also included in this set, along with newly composed works. The publication stood out for its originality and freshness of invention, as was noted by a reviewer writing a couple of years later on a musical review in Hamburg. “These sonatas are the only ones of their kind. They are rich in new ideas, showing traces of the great musical genius of their author…. Moreover, the violin accompaniment is so ingeniously combined with the piano part that both instruments are continuously employed; and thus these sonatas demand a violinist as accomplished as the pianist”. In fact, these works were conceived also as a showcase for their composer’s talent, both in writing and in performing music; and they certainly did not fail this task. In the first movement, the most interesting aspects are found in the development, which includes new, original elements and an attention for contrapuntal textures which is indeed very forward-looking.

The lyrical vein typical for Mozart, and particularly for his enchanted vocal themes, finds a beautiful outlet in the sweet second movement, featuring also a tight dialogue and interchange between the two instruments. The seemingly martial character of the third movement is far from belligerent. Rather, it is influenced, once more, by the metrical schemes of vocal music, where the march rhythm was frequently employed for the musical setting of some particular Italian metrical patterns.

The CD closes with one of the best-known examples of Mozart’s violin music. In this case, it is rather appropriate to speak of a “Violin” Sonata, since the violin’s part is highly concertante, very demanding and with a truly soloistic inspiration, in spite of the composer’s careful attention to the chamber music style of the work. This piece had been conceived on the occasion of the arrival in Vienna of a famous Italian violinist, Regina Strinasacchi, who was famous for the beauty of her tone and of her cantabile. Mozart clearly did his best in order to put his musical partner’s gifts into relief, and created a majestic, solemn, and touching piece, which is one of the favourites by violin players. Legend has it that Mozart was in such rush before the concert (where he played with Strinasacchi) that he had no time for writing down his own part. Since, at the time, playing by memory was not considered “professional”, he put a blank sheet of paper on the music stand. Whilst this last part of the anecdote is likely to be apocryphal (just as the fact that the Emperor noticed the blank sheet and asked for explanations), it is probable that Mozart did play from an unfinished manuscript, as is revealed by close inspection of the handwritten autograph. This does not prevent this Sonata from being an absolute masterpiece in the repertoire for violin and piano, and a cornerstone in the evolution of the genre.

Together, these Sonatas allow us to observe the evolution of Mozart’s thought on this genre, in spite of the relatively little time dividing them. Mozart’s genius was always in quest for novel ideas, and this, in turn, brought numerous coeval genres to their maturity thanks to Mozart’s unique contributions.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads