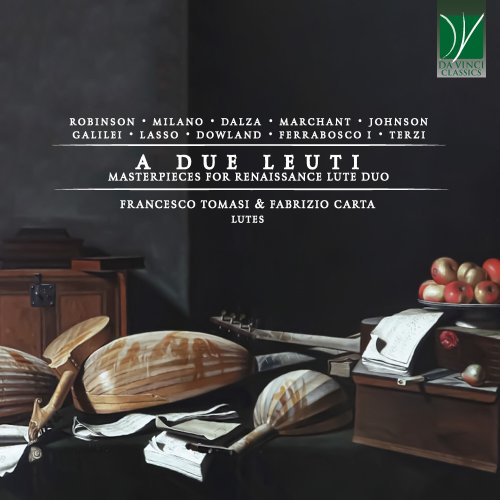

Francesco Tomasi, Fabrizio Carta - A due leuti (Masterpieces for Renaissance Lute Duo) (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Francesco Tomasi, Fabrizio Carta

- Title: A due leuti (Masterpieces for Renaissance Lute Duo)

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Lute

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:51:18

- Total Size: 233 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Plaine Song

02. Passemezo Galyard

03. The Queen's Goodnight

04. Fantasia a due leuti

05. Canone

06. La Spagna

07. Intabulatura de Lauto: No. 1, Saltarello

08. Intabulatura de Lauto: No. 2, Piva

09. Fantasy

10. Flat Pavan

11. Flat Galliard

12. Duo Tutto di Fantasia

13. Contrappunto I B.M.

14. Contrappunto II B.M.

15. Fantasia X

16. Fantasia IV

17. Fantasia IX

18. My Lord Willoughby's Welcome Home

19. The Spanish Pavan

20. Rogero

21. Canzone di Claudio da Correggio

With a certain approximation, it can be said that the lute is one of the “universals” of music. Certainly, it took a number of different forms and shapes depending on history and geography; yet, instruments whose structure is akin to it are found in virtually all cultures, and at times bear witness to the fundamental importance of this instrument for almost all musical contexts.

In Western Europe, it had one of the highpoints of its glory in the Renaissance. Unquestionably, given the elusive and fleeting nature of music, it is impossible to establish concretely how much, how commonly, and “how” it was played at the time.

Still, in this case we are fortunate, because what music in se loses by waning into an ultimately inexpressible manner, is at least partly recovered through visual arts and treatises. The extent to which the lute embodied the musical soul of the Renaissance and early Baroque era is abundantly witnessed by its pervasive and continuing presence in numerous paintings of the era. Doubtlessly, this is also due to the beauty of its physical shape, which blends magnificently with the harmonious portrayals of the human figure in the Renaissance. Its shape was also invested with a plurality of symbolic meanings, frequently becoming an icon for femininity thanks to its curved lines and elegant silhouette.

Curiously, however, an instrument which was so very common at the time is also very difficult to play. Normally, the more immediate the pleasure an instrument affords, the more widespread it becomes. However, we must correct what has been said above by fine-tuning it. The lute was one of the most common instruments only within a certain social-cultural milieu. Certainly, plucked-string instruments were found at all levels of musicianship, as it constantly happens throughout the musical cultures in history. But the lute proper was an instrument for the upper classes. The wealth of their members afforded them two benefits. On the one hand, they had plenty of leisure time – in certain cases, virtually all of their time was “free”. This allowed them to spend hours upon hours learning the complex art of lute playing. The only thing which distinguished them from music professionals, in certain cases, was that music professionals had to play in order to earn a living, whilst the aristocracy was not paid for playing.

On the other hand, the aristocrats and wealthy could employ salaried musicians to play for them, and also to teach them lute technique and interpretation. Their manors and castles were havens where the arts found generous patrons, very willing to depart from large sums of money in the pursuit of beauty, but also of social acceptance and recognition. (Interestingly, in the Renaissance art and music were a status symbol comparable to today’s yachts; and we owe to this recognition the presence of countless masterpieces of Renaissance art and music).

These aristocrats and wealthy had a lifestyle which virtually all members of the lower social classes would have profoundly envied. Yet, either sincerely – if it is true that money does not give happiness – or affectedly, they delighted in fashioning themselves as melancholic, oppressed by a grief not unlike that expressed by Mona Lisa’s smile. Not the intense pain of despair, or the tortured anguish of the soul; rather, the bittersweet expression of detachment from worldly affairs, of wise contemplation, and of an attitude towards love seen as a Platonic feeling, severed from the power of the passions.

These themes and subjects were also those found in contemporaneous vocal music, and in the poetry inspiring it in the form of lyrics set to music. They derived from Petrarchism, i.e. the Renaissance revival of subjects and manners found in Petrarch’s Canzoniere, where the pangs of love are ubiquitous, but they are so transfigured by beauty that nothing fleshy seems to remain between the lines of their texts.

And it was precisely from vocal music that the lute used to derive a substantial component of its repertoire. Being a polyphonic instrument – i.e. one on which multiple melodies could be played at a time, intertwining with each other in a beautiful fashion – the lute afforded the possibility for a single, individual player, to enjoy the intricacies of vocal counterpoint.

At times, however, this might be really very complex, particularly in the case of a high number of parts. And this applied both to transcriptions after vocal works, and to original pieces inspired by the forms, genres, and styles of vocal music. In that case, the possibility of sharing the difficulty and the pleasure of playing the lute with others was more than an excellent compromise – it was indeed a refined pleasure to be pursued for its own sake. Playing as a lute duet was a fundamental resource through which lute teachers and virtuoso lutenists could teach their noble pupils (or also those commoners who wanted to embark in the musical profession), and, at the same time, enjoy the complexity of musically rewarding works without all the labour and toil of playing them alone.

The works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album, therefore, are something akin to a time capsule allowing us to glimpse what gave musical pleasure to the musical, economic, and cultural elites of the Renaissance. These pieces were written by composers with diverse provenances and styles, and some of them are best known for other aspects of their output. Still, what virtually all of them have in common is the fact that all were excellent lutenists. And this is hardly surprising, since the lute (at the risk of oversimplifying it) was to the sixteenth century what the piano would be for the nineteenth century. (And it is unsurprising, under this viewpoint, that the repertoire for four-hand piano duet can be interpreted through the same lens we just discussed with respect to the lute duet).

Rather typically, Thomas Robinson was the private music tutor of the Danish royalty, teaching Princess Anne and Queen Sophie’s teacher. Robinson had gotten there after having served the Cecil family of British noblemen, who also sponsored William Byrd and Orlando Gibbons. Robinson’s pedagogical interest is also found in his The Schoole of Musicke, a treatise published in London in 1603, and which enjoyed enormous success to the chagrin of its competitors. It was his second publication (the first has been lost) and would be followed, six years later, by a new collection called New Citharean Lessons. The Schoole of Musicke provides information of the performance of a variety of instruments, including, besides the lute, the bandora, orpharion, viol, and singing too. Here we find several pieces written for two lutes, and possibly intended for pedagogical purposes in the broadest meaning of the term. The book includes 38 original works by Robinson along with some arrangements after popular songs; six pieces are duets, half of them based upon a ground. The book is prefaced by a witty and informative dialogue between a Knight who wants his children to be musically educated, and their teacher Timotheus; their conversation focuses on the costs and benefits of studying music, and the lute in particular.

Also Francesco da Milano had at one point an important job as the lute tutor of a noble youth. In this case, the nobility was that of the Roman curia; Francesco was given this role by Pope Paul III and taught the Pontiff’s nephew, Ottavio Farnese. Francesco da Milano was considered as the greatest lutenist of the era, and possibly of all times. He performed for the most important sovereigns, particularly when he followed his employer, the Pope, to Nice where the great of the world were discussing important international affairs. His works were printed in a number of European countries, and his worth was so unanimously acknowledged that he used to be called il divino as a homage to his exceptional talent and proficiency. Francesco introduced many French chansons into Italy. From these models (and particularly from those by Josquin) he derived novel perspectives on the composition of instrumental music. His surviving oeuvre comprises approximately a hundred ricercars and fantasias, 30 intabulations and other works. Francesco’s historical merit is to have favoured the transition from an improvisatory style to one bound to writing, shaped on the refinements of contemporaneous vocal music.

By way of contrasts, the focus of Joan Ambrosio Dalza’s surviving output is rather on dance. His aim seems to be that of creating delight and pleasure in music-making, by avoiding the most extreme difficulties of contrapuntal playing, and favouring instead the immediacy of dance movements. They are normally joined in threes, beginning with a pavane followed by a saltarello and piva.

Other composers were in turn attached to courts. Among them we can cite John Johnson, who worked for Queen Elisabeth, and whose music mirrors Italianate elements. Another example is that of John Dowland, the extraordinary lutenist who would have wished to be in her employ in turn, but failed to obtain the Queen’s favour and settled in Denmark (before obtaining the benevolence of King James I). Or we may cite Orlando di Lasso, who wandered from one court to another (his extreme skill as a composer for the voice was mirrored by his ability as a lute player). In other cases, the composer’s inside knowledge of courtly milieus and his frequent journeys as part of their employers’ display suggest the possibility that these musicians had a second life as spies. This is rather normally accepted as concerns Alfonso Ferrabosco I, who seemingly moonlighted as a secret service agent.

Ferrabosco belonged in a family of musicians, but so did Giovanni Antonio Terzi and Vincenzo Galilei. In Terzi’s case, the Augustinian father who recommended him affirmed that “his special profession is music, through which he was held in high esteem both in Italy and abroad”. He is remembered for his love for instrumental music: “With his voice he reproduced the harmony of heaven, but with his lute the voice of the angels”. Terzi introduced many substantial innovations in the playing techniques and repertoire, and their complexity is witnessed by his publications where his own virtuosity is abundantly demonstrated. Another important family was that of the Galilei, whose best-known member is doubtlessly Galileo. However, his father Vincenzo was one of the finest musicians and thinkers of the era and probably encouraged his son in the pursuit of his historical experiments.

Together, these works allow the full palette of the techniques, moods, genres, and styles of Renaissance lute music to emerge, but possibly empowered and potentiated by the presence of two instruments in dialogue with each other. If a good thing lived in loneliness remains a good thing, one shared with somebody else becomes exceptional.

01. Plaine Song

02. Passemezo Galyard

03. The Queen's Goodnight

04. Fantasia a due leuti

05. Canone

06. La Spagna

07. Intabulatura de Lauto: No. 1, Saltarello

08. Intabulatura de Lauto: No. 2, Piva

09. Fantasy

10. Flat Pavan

11. Flat Galliard

12. Duo Tutto di Fantasia

13. Contrappunto I B.M.

14. Contrappunto II B.M.

15. Fantasia X

16. Fantasia IV

17. Fantasia IX

18. My Lord Willoughby's Welcome Home

19. The Spanish Pavan

20. Rogero

21. Canzone di Claudio da Correggio

With a certain approximation, it can be said that the lute is one of the “universals” of music. Certainly, it took a number of different forms and shapes depending on history and geography; yet, instruments whose structure is akin to it are found in virtually all cultures, and at times bear witness to the fundamental importance of this instrument for almost all musical contexts.

In Western Europe, it had one of the highpoints of its glory in the Renaissance. Unquestionably, given the elusive and fleeting nature of music, it is impossible to establish concretely how much, how commonly, and “how” it was played at the time.

Still, in this case we are fortunate, because what music in se loses by waning into an ultimately inexpressible manner, is at least partly recovered through visual arts and treatises. The extent to which the lute embodied the musical soul of the Renaissance and early Baroque era is abundantly witnessed by its pervasive and continuing presence in numerous paintings of the era. Doubtlessly, this is also due to the beauty of its physical shape, which blends magnificently with the harmonious portrayals of the human figure in the Renaissance. Its shape was also invested with a plurality of symbolic meanings, frequently becoming an icon for femininity thanks to its curved lines and elegant silhouette.

Curiously, however, an instrument which was so very common at the time is also very difficult to play. Normally, the more immediate the pleasure an instrument affords, the more widespread it becomes. However, we must correct what has been said above by fine-tuning it. The lute was one of the most common instruments only within a certain social-cultural milieu. Certainly, plucked-string instruments were found at all levels of musicianship, as it constantly happens throughout the musical cultures in history. But the lute proper was an instrument for the upper classes. The wealth of their members afforded them two benefits. On the one hand, they had plenty of leisure time – in certain cases, virtually all of their time was “free”. This allowed them to spend hours upon hours learning the complex art of lute playing. The only thing which distinguished them from music professionals, in certain cases, was that music professionals had to play in order to earn a living, whilst the aristocracy was not paid for playing.

On the other hand, the aristocrats and wealthy could employ salaried musicians to play for them, and also to teach them lute technique and interpretation. Their manors and castles were havens where the arts found generous patrons, very willing to depart from large sums of money in the pursuit of beauty, but also of social acceptance and recognition. (Interestingly, in the Renaissance art and music were a status symbol comparable to today’s yachts; and we owe to this recognition the presence of countless masterpieces of Renaissance art and music).

These aristocrats and wealthy had a lifestyle which virtually all members of the lower social classes would have profoundly envied. Yet, either sincerely – if it is true that money does not give happiness – or affectedly, they delighted in fashioning themselves as melancholic, oppressed by a grief not unlike that expressed by Mona Lisa’s smile. Not the intense pain of despair, or the tortured anguish of the soul; rather, the bittersweet expression of detachment from worldly affairs, of wise contemplation, and of an attitude towards love seen as a Platonic feeling, severed from the power of the passions.

These themes and subjects were also those found in contemporaneous vocal music, and in the poetry inspiring it in the form of lyrics set to music. They derived from Petrarchism, i.e. the Renaissance revival of subjects and manners found in Petrarch’s Canzoniere, where the pangs of love are ubiquitous, but they are so transfigured by beauty that nothing fleshy seems to remain between the lines of their texts.

And it was precisely from vocal music that the lute used to derive a substantial component of its repertoire. Being a polyphonic instrument – i.e. one on which multiple melodies could be played at a time, intertwining with each other in a beautiful fashion – the lute afforded the possibility for a single, individual player, to enjoy the intricacies of vocal counterpoint.

At times, however, this might be really very complex, particularly in the case of a high number of parts. And this applied both to transcriptions after vocal works, and to original pieces inspired by the forms, genres, and styles of vocal music. In that case, the possibility of sharing the difficulty and the pleasure of playing the lute with others was more than an excellent compromise – it was indeed a refined pleasure to be pursued for its own sake. Playing as a lute duet was a fundamental resource through which lute teachers and virtuoso lutenists could teach their noble pupils (or also those commoners who wanted to embark in the musical profession), and, at the same time, enjoy the complexity of musically rewarding works without all the labour and toil of playing them alone.

The works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album, therefore, are something akin to a time capsule allowing us to glimpse what gave musical pleasure to the musical, economic, and cultural elites of the Renaissance. These pieces were written by composers with diverse provenances and styles, and some of them are best known for other aspects of their output. Still, what virtually all of them have in common is the fact that all were excellent lutenists. And this is hardly surprising, since the lute (at the risk of oversimplifying it) was to the sixteenth century what the piano would be for the nineteenth century. (And it is unsurprising, under this viewpoint, that the repertoire for four-hand piano duet can be interpreted through the same lens we just discussed with respect to the lute duet).

Rather typically, Thomas Robinson was the private music tutor of the Danish royalty, teaching Princess Anne and Queen Sophie’s teacher. Robinson had gotten there after having served the Cecil family of British noblemen, who also sponsored William Byrd and Orlando Gibbons. Robinson’s pedagogical interest is also found in his The Schoole of Musicke, a treatise published in London in 1603, and which enjoyed enormous success to the chagrin of its competitors. It was his second publication (the first has been lost) and would be followed, six years later, by a new collection called New Citharean Lessons. The Schoole of Musicke provides information of the performance of a variety of instruments, including, besides the lute, the bandora, orpharion, viol, and singing too. Here we find several pieces written for two lutes, and possibly intended for pedagogical purposes in the broadest meaning of the term. The book includes 38 original works by Robinson along with some arrangements after popular songs; six pieces are duets, half of them based upon a ground. The book is prefaced by a witty and informative dialogue between a Knight who wants his children to be musically educated, and their teacher Timotheus; their conversation focuses on the costs and benefits of studying music, and the lute in particular.

Also Francesco da Milano had at one point an important job as the lute tutor of a noble youth. In this case, the nobility was that of the Roman curia; Francesco was given this role by Pope Paul III and taught the Pontiff’s nephew, Ottavio Farnese. Francesco da Milano was considered as the greatest lutenist of the era, and possibly of all times. He performed for the most important sovereigns, particularly when he followed his employer, the Pope, to Nice where the great of the world were discussing important international affairs. His works were printed in a number of European countries, and his worth was so unanimously acknowledged that he used to be called il divino as a homage to his exceptional talent and proficiency. Francesco introduced many French chansons into Italy. From these models (and particularly from those by Josquin) he derived novel perspectives on the composition of instrumental music. His surviving oeuvre comprises approximately a hundred ricercars and fantasias, 30 intabulations and other works. Francesco’s historical merit is to have favoured the transition from an improvisatory style to one bound to writing, shaped on the refinements of contemporaneous vocal music.

By way of contrasts, the focus of Joan Ambrosio Dalza’s surviving output is rather on dance. His aim seems to be that of creating delight and pleasure in music-making, by avoiding the most extreme difficulties of contrapuntal playing, and favouring instead the immediacy of dance movements. They are normally joined in threes, beginning with a pavane followed by a saltarello and piva.

Other composers were in turn attached to courts. Among them we can cite John Johnson, who worked for Queen Elisabeth, and whose music mirrors Italianate elements. Another example is that of John Dowland, the extraordinary lutenist who would have wished to be in her employ in turn, but failed to obtain the Queen’s favour and settled in Denmark (before obtaining the benevolence of King James I). Or we may cite Orlando di Lasso, who wandered from one court to another (his extreme skill as a composer for the voice was mirrored by his ability as a lute player). In other cases, the composer’s inside knowledge of courtly milieus and his frequent journeys as part of their employers’ display suggest the possibility that these musicians had a second life as spies. This is rather normally accepted as concerns Alfonso Ferrabosco I, who seemingly moonlighted as a secret service agent.

Ferrabosco belonged in a family of musicians, but so did Giovanni Antonio Terzi and Vincenzo Galilei. In Terzi’s case, the Augustinian father who recommended him affirmed that “his special profession is music, through which he was held in high esteem both in Italy and abroad”. He is remembered for his love for instrumental music: “With his voice he reproduced the harmony of heaven, but with his lute the voice of the angels”. Terzi introduced many substantial innovations in the playing techniques and repertoire, and their complexity is witnessed by his publications where his own virtuosity is abundantly demonstrated. Another important family was that of the Galilei, whose best-known member is doubtlessly Galileo. However, his father Vincenzo was one of the finest musicians and thinkers of the era and probably encouraged his son in the pursuit of his historical experiments.

Together, these works allow the full palette of the techniques, moods, genres, and styles of Renaissance lute music to emerge, but possibly empowered and potentiated by the presence of two instruments in dialogue with each other. If a good thing lived in loneliness remains a good thing, one shared with somebody else becomes exceptional.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads