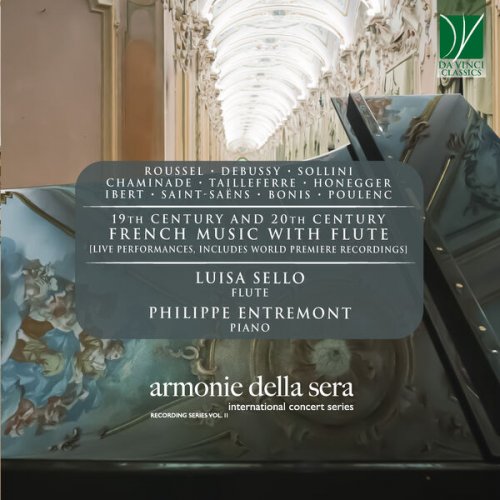

Tracklist:

01. Joueurs de flûte, Op. 27: I. Pan (For Flute and Piano)

02. Joueurs de flûte, Op. 27: II. Tityre (For Flute and Piano)

03. Joueurs de flûte, Op. 27: III. Krishna (For Flute and Piano)

04. Joueurs de flûte, Op. 27: IV. Mr. de la Péjaudie (For Flute and Piano)

05. Syrinx, L. 129 (For Flute)

06. À la manière de....Bach, Op. 42 (For Flute)

07. Canzona, Op. 39 (For Flute and Piano)

08. Piece Romantique, Op. 9 (For Flute and Piano)

09. Pastorale (For Flute and Piano)

10. Danse de la Chèvre, H. 39 (For Flute)

11. Une flûte soupire, Op. 121 (For Flute and Piano)

12. Piece (For Flute)

13. Romance, Op. 37 (For Flute and Piano)

14. Sonata, FP 164: I. Allegro malinconico (For Flute and Piano)

15. Sonata, FP 164: II. Cantilena (For Flute and Piano)

16. Sonata, FP 164: III. Presto giocoso (For Flute and Piano)

The gorgeous programme featured on this Da Vinci Classics album takes us into a fascinating journey among some of the best known works of the entire flute repertoire, but also touching some lesser known pieces and including the world premieres of two contemporary works. Listening to this CD, therefore, is granted to represent a stimulating and ever-varied experience, where a mosaic of styles and suggestions is likely to capture the listener’s attention. At the same time, it is most emphatically not a piecemeal programme, in spite of the number of artists represented. There are some evident red threads, and others which will be hopefully enlightened by the following discussion.

Probably, the principal unifying trait of all works on this CD can be summed up as a question: how can the musical present relate with the musical past? Music is perhaps the most temporal of all arts; it lives in time, dies in time (except when, as is the case with this CD, a providential recording captures the elusiveness and spontaneity of a live performance), but also structures time thanks to its articulation of time. Music prescribes time (for instance, through indications of tempo and speed), and projects its own temporality on that of the listener, replacing clock time with its own psychological time.

Due precisely to the fleetingness of music, it has begun to be preserved only very recently, thanks to the recording techniques whose first examples date from approximately 150 years ago (with the most rudimentary “recordings”). And only at the beginning of the nineteenth century had the idea of a “history of music” become common, together with a new interest in the preservation and performance of the masterpieces of the past. Thus, whereas we have an immense documentation about, say, Greek art (which has inspired, or rather dictated the rules, to generations of artists for millennia), we have only a very scanty and extremely rare documentation about the music of the ancient Greeks; even less do we know about how it actually sounded.

This, on the one hand, is an irrecoverable loss, for which we musicians constantly mourn. What would we give for the possibility of listening to half an hour of “real” Greek music, or for a performance by Bach or by Mozart…! This loss, however, is not without its compensations, albeit inadequate. In spite of an actual experience of audible Greek music (such as we have experiences of actual Greek sculpture) we have our fantasy, our imagination, our creativity. And while musicologists seriously attempt to recover at least some traces of the “original” sound of that music, musicians simply draw their own idea of “Greek” music from the repository of musical imagination, at times supported by the little we do know about it. For instance, a field which is abundantly documented is that of music theory: here we are well informed about the names and structures of the Greek scales, even if we know only slightly how they were employed by Greek artists.

This, as said, did not prevent numerous musicians, especially from the late nineteenth century onwards (when musicological studies began to “reconstruct” Greek music) from imagining their “sound” for a fictional and fictive Greekness. Indeed, ancient Greece had found its way into the Western musical repertoire from a much earlier period (already in the Humanism and Renaissance), but only very occasionally did the Baroque or Classical musicians attempt to give a patina of “authentic Greekness” to their music. In the best cases, something sounding “archaic” had been taken as representing Greek classicism, or snatches from contemporaneous folk music (e.g. from the pastoral repertoire) became iconic of Greek Arcadia.

Among the things which were known since always, of course, were the tales of the mythical Greek musicians: Apollo, the god of music; the Muses; Orpheus with his enchanted cithara; Alcyon; the tales of Pan and Marsyas; and so on.

It is from one of the tales regarding Pan that one of the most famous of the pieces recorded here is excerpted. Claude Debussy was deeply fascinated by the flute and by Greece (and this should give us pause when uncritically speaking of Debussy’s “Impressionism”, since Neo-classicism is at the antipodes of Impressionism, and yet is frequently found in Debussy’s oeuvre).

Syrinx was written in 1913, and belongs in a conspicuous series of Pan-inspired works by Debussy (including, most famously, the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, but also Fêtes galantes and one of the Six Epigraphes Antiques). Indeed, the very title of this piece should have alluded in turn to Pan (it was originally planned to be Flute de Pan), but later Debussy changed his mind and decided to celebrate Pan’s victim, the nymph Syrinx, rather than her pursuer, the half-man, half-goat faun Pan. The piece was originally conceived after a commission by Gabriel Mourey, for whose play Psyché Debussy’s work should have provided incidental music. The fluctuations in the piece’s temporality are one of the strategies employed by Debussy in order to point out the “temporal exoticism” of this piece. At the same time, these fluctuations happen within an extremely carefully prescribed score, where Debussy’s love for precision becomes the instrument through which the capricious style of the faun’s improvisation can happen.

I have just employed the word “capricious”, which, as some might not know, derives from the Latin caprizare, i.e., leaping as a goat. Thus, Paganini’s Capriccios would literally refer to musical pieces whose ungraspable structure is as elusive and fantastic as a goat’s unpredictable behaviour. (Of course, Paganini’s Capriccios have normally a very clear musical form, but the “capricious” aspect lies in their seemingly improvisational handling of the technical difficulties). Thus, the goat-leaps of the faun Pan seem to appear also in Arthur Honegger’s Danse de la chèvre, “Dance of the Goat”. Honegger crafted this short and enthralling piece by jumps and leaps, particularly found in the chromatic alterations of the F-major theme. This piece was written in 1921 and was planned to constitute an element of incidental music for a choreography to be performed by Lysana within a play by Sacha Derek, by the title of La mauvaise pensée. The piece was dedicated to René Le Roy, and makes abundant use of the tritone, the “mauvais” (bad, evil) interval.

Pan returns also in a suite written three years later (1924) by Albert Roussel, and focusing on four mythical flute players.

The suite’s first movement is titled Pan, in fact, and is dedicated to Marcel Moyse, to whom also Ibert’s Pièce is dedicated. In homage to Pan’s “Greekness”, the piece employs the Greek Dorian mode (as said before, Greek modes were one of the few commonly known things about Greek music). The second piece focuses on Tityre, a character in Virgil’s Eclogues, whilst the third is dedicated to the Hindu god Krishna, who is said to have been a divine herdsman. Here too Roussel employs an “exotic” scale, i.e. a Raga from the North-Indian tradition. This movement is dedicated to Louis Fleury, the dedicatee also of Debussy’s Syrinx. Finally, the protagonist of the fourth piece is “Monsieur de la Péjaudie”, a fictional character with a rather libertine approach to life.

I have just cited Ibert’s Pièce, premiered by Moyse. This piece quotes from Ibert’s Flute Concerto, after which it was originally performed, and has some of Ibert’s “capriciousness” in turn. In particular, it embodies Ibert’s penchant for the Classical style, which is one of the main traits of his aesthetics. This is a characteristic shared also by one of the most celebrated works of all flute literature, i.e. Poulenc’s Sonata, with its skilful alternation of bittersweet melancholy, witticism, energy, irony and lyricism. In its three short movements, it wonderfully displays its composer’s style and personality, as generations of flutist have willingly demonstrated. This piece was dedicated to the American patroness of modern music, Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, and frequently performed by the composer himself at the piano, together with some of the greatest flutists of all times.

Melancholy is also abundantly found in Saint-Saëns’ Romance, which beautifully embodies both the grief of the Franco-Prussian war (1870-1) and the desire for peace and hope after it, just as many of the other works recorded here allude to the two World Wars, or to other humanitarian crises (as happens with Sollini’s works, composed during the Covid pandemic). For instance, the sweetness and grace of Germaine Tailleferre’s Pastorale acquire a much greater poignancy if one considers it was written in the darkest days of World War II, in 1942. A similar evocation of the “pastoral” atmospheres of the mythical Arcadia is found in the other work written by a female composer and recorded here, a Pièce romantique of great grace and sweetness by Cécile Chaminade.

As said earlier, Sollini’s Canzona, written in November 2020, expresses both the mourning and the hope lived by the composer, as by many other human beings, during the first outburst of the Covid pandemic. Sollini’s A la manière de… Bach is scored for solo flute, and alludes to Bach’s unequalled handling of counterpoint, thus paying homage, with modern eyes, to a master of the past.

Here the circle closes, in a manner of speaking. The “history” of music becomes a living and lived experience. Sollini’s own, direct experience of Bach’s music as a performer, as a teacher and as a composer translates into a homage where past and present really speak with each other. And this all happens within the context of a concert, whose live experience will remain always in the memory of its listeners, but whose recorded shape is handed down through this CD. Music, then, can even transcend time, the medium of its realisation and the world it quintessentially inhabits. And it can live on not only in memory, but also in a musical recording.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2021