Tracklist:

1. Stella Timenova – Phos - La via della luce: Preambolo (04:41)

2. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: I. Quel vago istante (04:40)

3. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: II. Dall’abisso (03:48)

4. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: III. La luce nega (03:10)

5. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: IV. Al crepuscolo (06:38)

6. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: V. Il giuramento (02:30)

7. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: VI. L’invocazione (03:16)

8. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: VII. Ciò che la luce è per l’ombra (00:59)

9. Stella Timenova – Phos - La via della luce: Interludio (04:01)

10. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: VIII. La Luna (04:30)

11. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: IX. Nel buio (04:53)

12. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: X. Il sacrificio (06:10)

13. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: XI. La via della Luce (05:29)

14. Stefanna Kybalova – Phos - La via della luce: XII. La sorgente (04:50)

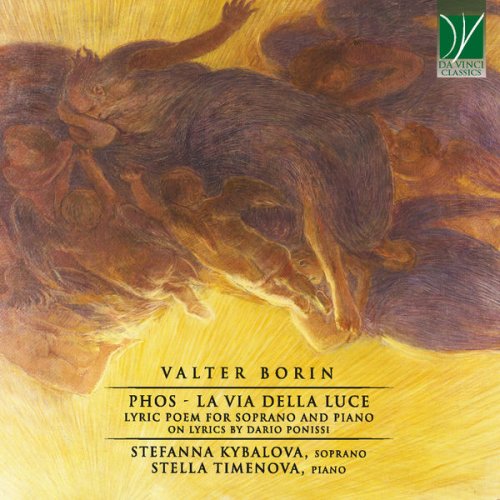

Phos – La via della luce takes its name from the ancient Greek name for light, phos, and from a subtitle meaning “the way of light” in Italian. Light is a universal symbol, suggesting all kinds of positive associations to human beings of all cultures, of all religions, and of all times. In many languages, to be born is to “come to light”, and, by way of contrast, all kinds of dark and shadowy imagery are connected with death, evil, and despair. These symbols are deeply woven into the fabric of Phos – La via della luce, which is a powerful and intense itinerary into the mystery of death, of life, of love, of goodness, of self-sacrifice, of generosity, of despair, and of hope. The authors of this work do not eschew a dramatic confrontation with the deepest fears, with the most provoking questions, and with the unsolved mysteries of human existence.

The idea for this composition came into being in what in hindsight seems the most unlikely of all places: at a Tokyo restaurant, where friends were chatting, and after an idea by the composer’s wife. Gradually, the idea took shape, and, little by little, author Dario Ponissi began sending to composer Valter Borin the lyrics which would constitute the textual element of Phos. “Little by little” should be taken literally: the poems were not written on the spur of the moment, and they steadily kept coming for almost two years. This dictated the pace of the compositional process. On the one hand, the poems were sent in the same order as they now appear in the recorded version presented in this Da Vinci Classics album. This allowed the two authors to “follow”, in a manner of speaking, the protagonist’s interior itinerary and what happens around and inside her. On the other hand, the dilution of the artistic process was challenging in itself. As the composer puts it, “It has been a hard work. In the course of two years, people change. Maybe the change is small, but it still is there. I had to find a way to impart unity to the work within that change: it was a task within the task. Music performers frequently evolve from a more brilliant and virtuosic approach, one marked by elan and impetus, toward a more shaded and reflective stance. For a composer, it implies to keep seeking a balance, a spiritual companionship with the lyrics’ author, in the quest for a shared poetical unity”. In other words, whereas the composer of a texted musical work normally has “just” to seek an artistic unity between the music he or she writes and the text they receive, in this case both artists had to seek an understanding also with their former selves.

In turn, this process was not without its benefits, difficult and complex as it could be: “I later realized that I was approaching more easily other works I wrote later, for orchestra or for piano, and that I was referring to a more patent simplicity”, as Borin states.

The style of the lyrics also required a thoughtful approach. The composer admits that he had to adapt his way of composing to the kind of poetics and of words he was receiving: “It was a rather cryptic, unusual style, which I felt as being close to Expressionism – a kind of post-Expressionism”. The composer then sought atmospheres which could express the piece’s main point: an itinerary from darkness to light. The result is a composition that could be understood as a Lieder-cycle, but that the composer prefers labelling as a “lyrical poem”. It is interwoven with musical references, with elements returning at some distance in time, and which assume a different meaning depending on the time passing from their first to their next appearance. The listener’s perspective is thus influenced by what has happened in between. The result was a meditative kind of writing: “It was not a sudden inspiration, but rather a very deliberate and thoughtful composition. I needed time for thinking, and for seeking a balance amidst the various components”.

On the technical plane, the two media of sound production – i.e. the voice and the piano – have an equally important role: neither prevails, and both concur to the quest for a same way, a same manner, and toward a same result. Their common goal is a sound path leading to a hypothetical light and a salvation. “I sparsely employed particular aural effects; in no case, however, as a form of narcissism or deliberately imitating other composers’ styles. My music came about from the words and from the plot”. At the same time, the two wordless movements, the Preamble and the Interlude, are among the composer’s most cherished moments. “The Preamble substantially represents in music the protagonist’s run. She is about to accomplish an extreme deed, so we witness her rushing upwards. Then there is a moment when she possibly stops to recall her memories, and then she starts again. A very brusque stop should symbolize her getting to the border of the abyss, where the entire story begins”. Similarly, the interlude (the only other piece for solo piano) is marked by an especially intense lyricism: “It is as if the voice, at that moment, were unable to say what it should say, and then it entrusts that message to the piano”.

Technically, the result is very challenging: both the piano and the voice face arduous performing tasks. Here too, however, these do not result from self-complacency: “I needed these means to reach a particular sound effect for a specific sentence or dramaturgic moment. Or for highlighting them, or for countering or overturning them… In short, to give an interpretation of mine to the words. So it was necessary for me to employ some artifices which technically translate into as many hardships”. The compositional process, therefore, was slow and unhurried; and this in turn contrasts with Borin’s more usual approach, which is more direct and immediate. “For this work, instinct and technique were not enough. It was necessary to channel and to elaborate what instinct told me. I needed to reflect on it”.

The result is a profound, intense, fascinating itinerary: “What I would like most, with this work, is that a potential listener could receive emotions from this experience. There are many emotions here, a full palette of them: from darkness to light”.