Tracklist:

1. Riverwalk (06:11)

2. PickledGinger 1 (00:14)

3. Gratitude (06:18)

4. PickledGinger 2 (00:16)

5. Acclimation Park (05:40)

6. PickledGinger 3 (00:18)

7. Ridgewood (06:45)

8. PickledGinger 4 (00:17)

9. Renate (05:44)

10. PickledGinger 5 (00:17)

11. Inclusion (07:04)

12. PickledGinger 6 (00:33)

13. Chill'n (07:44)

14. What Have I Done? (03:20)

Personnel:

Gary Versace - piano

Drew Gress - bass

Tom Rainey - drums

Ed Neumeister - trombone

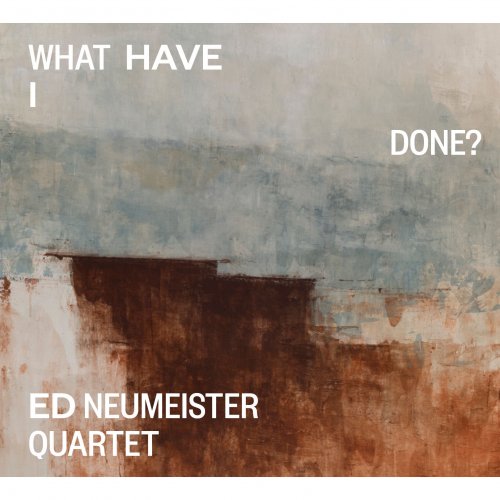

Ed Neumeister Quartet, What Have I Done?

Ed Neumeister has done more than simply establish a sound on the trombone. To hear him play is to experience a whole array of sounds. On What Have I Done?, an engaging set of originals with pianist Gary Versace, bassist Drew Gress and drummer Tom Rainey, we hear many of them: open trombone sounds, plunger with pixie mute, plunger alone (or “open plunger”), straight mute and cup mute — sometimes more than one in the course of the same piece.

The album title asks what Neumeister has done, and perhaps we can venture an answer: what he’s doing with all these sounds is orchestration, creating colors and moods, even in a setting as compact as a jazz quartet. He is, after all, not only a veteran jazz improviser but a composer for string quartet, wind quintet, jazz orchestra, even symphony orchestra. Color and timbre are integral to his compositional process. Neumeister’s sonic palette has been evolving, whether it’s small or large ensemble or even solo unaccompanied, as his 2019 release One and Only so clearly illustrates.

“I told Gary [Versace] that this is not a blowing record, it’s a recording of compositions that incorporates improvisation,” says Neumeister. “For the last 30 years I compose every day — it’s part of my daily routine. It started via the BMI Jazz Composers Workshop in 1987. I was in the first group with Bob Brookmeyer and Manny Albam, which is when I morphed from a trombonist who composes to a composer whose instrument is the trombone.”

Grappling with Neumeister’s notated music can therefore be an undertaking, as Versace well knows. But having logged roughly 10 years in trio settings with Neumeister and vocalist Jay Clayton, as well as Neumeister’s jazz orchestra on occasion, the pianist was wholly receptive and ready to give his all.

“Gary and I spent two or three weeks with numerous phone calls,” the leader recalls. “The way I notate this music, I have this big picture in mind so I’m not really writing a piano part, I’m writing an orchestra part. It’s Gary’s job, in consultation with me, to decide what to play and what to leave out, because it’s impossible to play everything that’s written, but that’s not the point. I wanted to put all the material there so we could decide, do we double the melody or bass or not, is there comping or fills in between or not, for example. Once he got a handle on it, he was able to play what he wanted, but still coming from what I wrote. He was judicious about respecting what was there, and able to contribute his unique voice at the same time.”

With Gress and Rainey on bass and drums, the quartet has a rhythm team as solid and strong as it is flexible. Gress and Rainey have worked together extensively in Tim Berne’s Paraphrase trio as well as Tony Malaby’s Apparitions, the Ingrid Laubrock Octet and not least of all Rainey’s own Obbligato quintet, among others. Gress was also a member of Neumeister’s earlier quartet with John Hollenbeck on drums and the late Fritz Pauer on piano, captured on the albums New Standards, Reflection and the upcoming freely improvised Explorations.

The connection between Neumeister and Rainey goes back the farthest, from their time together in the Bay Area to their move to New York in the early ’80s, when the loft scene was still in bloom and the two would go from place to place, playing sessions routinely.

This quartet is rooted in a history even deeper by virtue of the legacy Neumeister is drawing from on the horn. As a member of the post-1974 Ellington band, he played all the trombone features made famous by plunger mute pioneer Joe “Tricky Sam” Nanton (1904-46) and his successors. With the Mel Lewis Orchestra (formerly Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra, now Vanguard Jazz Orchestra), Neumeister did extensive plunger work as well; Jim McNeely wrote him a big-band plunger concerto, in fact, “Sticks,” from the VJO’s 1997 release Lickety Split: Music of Jim McNeely. Today, whatever the context, Neumeister is likely to integrate the plunger sounds across the duration of an album or concert, rather than as a lone special feature.

This recording is also a product of Neumeister’s return to the New York scene in 2017. A Bay Area native, he swam in New York’s deep musical waters for 20 years or so before starting a 17-year gig as a professor at the University of the Performing Arts in Graz, Austria. He then segued to Los Angeles, orchestrating for films such as Inception, The Dark Night Rises and Sherlock Holmes, before returning to the New York area and his current home in downtown Newark, New Jersey. That too is the history informing this album, beginning with “Riverwalk,” a bright jazz waltz, dedicated to the late, great Chick Corea and inspired by Neumeister’s daily walks along the Passaic River. “Acclimation Park,” too, is named for a favorite jogging site in São Paulo, hence the slow samba feel. “It’s really traditional in regard to functional harmony and four-bar phrases but it’s got some strange melody notes,” Neumeister remarks. “I’m altering chords that aren’t so often altered.”

The “PickledGinger” interludes, very brief palate cleansers sequenced between the tunes, were initially performed as one continuous free improvisation, then split up into separate tracks to fulfill the desired function. “Each free piece had minimal organization, but some,” he says. “This was the third improv we did in the studio — I gave a basic form before we started. We’d each do a short solo, and then it goes … wherever.”

There’s more of that species of interplay, what Neumeister calls “group ad lib,” informing the free section of “Chill’n,” which is based on the Phrygian mode. Also significant is the way Neumeister can take melodic material to refreshingly new places in the A and B sections of a piece, for instance on “Gratitude.” On this and others, Neumeister clarifies, “There’s often what looks like chord changes, but I don’t think of them as chord changes anymore, I call them harmonic reference. The improv section is based on an invented scale, the eight notes of which are written out, coming again from the original source material of the theme.”

“Ridgewood” is named for the Queens neighborhood where Neumeister was staying when he wrote it. “A lot of my music is mixed meters,” he notes. “This one is funky but the first bar is in 9/8 and the second bar is in 17/16, and it goes back and forth between those and then 5/8 and 11/16 giving it a quirky kind of free-form limping dance. But the written meters are almost irrelevant, it’s about the rhythms.”

This prompts Neumeister to observe about the album as a whole: “This is a jazz record and there’s a fair amount of swing and other feels, but the bass never walks. The bass part on ‘Ridgewood’ is all notated — it’s based on a tone-row, using classical composition techniques, no chord changes.” Composed for a dear departed friend from Switzerland, “Renate” is more tonal and “sing-songy” in approach, Neumeister says, “though harmonically far away from II-V-I.” It’s built on a pattern in 10/4, he adds — two bars of 3/4 and one bar of 4/4 with a swing feel reminiscent of Elvin Jones.

“What Have I Done?” is a perennially human question we might ask at any major crossroads — in Neumeister’s case at the end of a marriage and the start of a new relationship. The piece is derived from material he had used in a string quartet, the impetus of which was to compose something in C# minor. “It’s two choruses,” Neumeister says. “No real improvisation except from Tom and Gary a little bit.”

Again, we might rephrase the question while hearing this concluding piece play out: What, indeed, has Neumeister done? With this recording he’s done something vital. He’s not only assembled a band of top-tier colleagues but also challenged them, taking his writing to new places in the process, building on a deep and worthy catalogue of recordings as one of the finest trombone exponents of our day.

David R. Adler