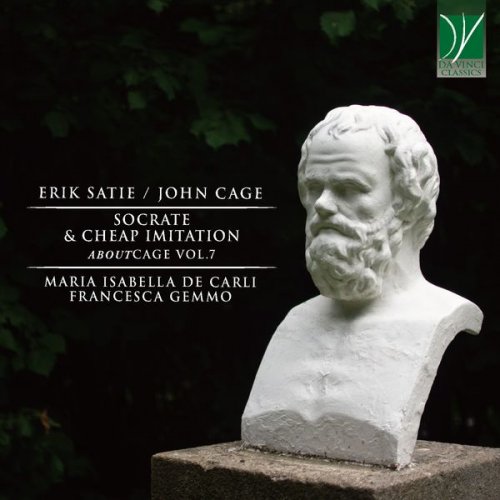

Maria Isabella De Carli & Francesca Gemmo - Eric Satie/John Cage: Socrate - John Cage: Cheap Imitation (AboutCage Vol. 7) (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Maria Isabella De Carli, Francesca Gemmo

- Title: Eric Satie/John Cage: Socrate - John Cage: Cheap Imitation (AboutCage Vol. 7)

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 1:09:30

- Total Size: 181 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

1. Maria Isabella De Carli – Socrate: I. Portrait of Socrates (Version For Two Pianos By John Cage) (06:24)

2. Maria Isabella De Carli – Socrate: II. On the Banks of Ilissus (Version For Two Pianos By John Cage) (07:06)

3. Maria Isabella De Carli – Socrate: III. Death of Socrates (Version For Two Pianos By John Cage) (20:03)

4. Francesca Gemmo – Cheap Imitation: I. (For Piano) (08:10)

5. Francesca Gemmo – Cheap Imitation: II. (For Piano) (08:34)

6. Francesca Gemmo – Cheap Imitation: III. (For Piano) (19:11)

1. Maria Isabella De Carli – Socrate: I. Portrait of Socrates (Version For Two Pianos By John Cage) (06:24)

2. Maria Isabella De Carli – Socrate: II. On the Banks of Ilissus (Version For Two Pianos By John Cage) (07:06)

3. Maria Isabella De Carli – Socrate: III. Death of Socrates (Version For Two Pianos By John Cage) (20:03)

4. Francesca Gemmo – Cheap Imitation: I. (For Piano) (08:10)

5. Francesca Gemmo – Cheap Imitation: II. (For Piano) (08:34)

6. Francesca Gemmo – Cheap Imitation: III. (For Piano) (19:11)

The history of human thought, not only as concerns Western civilization, would be entirely different without Socrates and Plato. Of course, these two master thinkers belonged in a long line of Greek philosophers, to whose thought they reacted, accepting some of their statements whilst refusing others. Still, what we owe to Socrates and Plato is impossible to estimate, but certainly is a substantial part of our worldview.

Indeed, we have not a single line written by Socrates; all we know about him comes from Plato’s Dialogues. Yet, since Plato himself was much more than a passive chronicler or an “objective” observer, we may often wonder how much of Plato’s “Socrates” comes from Socrates himself, and how much is the result of Plato’s afterthoughts on his teacher’s speeches.

Still, this is and will remain an unanswered and unanswerable question. What we do have is the magnificent repertoire of Plato’s Dialogues, which exemplify – as very few other works of art do – the power of the word, of the logos, of the dialectic encounter among human beings mediated by speech, and how speech influences the very forms (or ideas, as Plato would have put it!) of our thought.

The curious aspect of the works recorded here is that they are objectively grounded on and derived from the text of Plato’s Dialogues, but are wordless. The effect is similar to what happens when, for instance, the drama where “words, words, words” is uttered (i.e. Shakespeare’s Hamlet) is turned into a symphonic poem, as in Čajkovskij’s eponymous work. In principle, the idea seems very bizarre and abstruse: take Shakespeare’s “words” from Hamlet and what remains is a rather absurd plot, which, moreover, will not be understood by following the musical score alone. Still, the result can be a masterpiece, if the composer is imaginative and creative enough – as happens, in fact, with Čajkovskij’s symphonic poem.

We cited Čajkovskij’s Hamlet, but we might also have cited Hector Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette, a mammoth symphonic poem which narrates, in over one and a half hour, the story of Shakespeare’s unfortunate lovers. And it is precisely from Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette that Erik Satie took inspiration for his Socrate. “To take inspiration”, however, should be understood in the very idiosyncratic way required every time we deal with Satie. Berlioz’s work is majestic, long, rich in themes and timbres, sounds and ideas, to the point that it can be slightly overwhelming. It narrates the quintessential love story in an involving and touching fashion.

By way of contrast, Satie’s Socrates is much shorter, it involves verbality, it is very essential under the viewpoint of timbre, and, from the narrative viewpoint, it is so bare that it can be said to be no story at all. However, there is a “story” behind this Da Vinci Classics album, and we will try to tell it.

This album includes two works by John Cage, which both relate, directly or indirectly, with Satie’s Socrate. And it is from this composition that we will start our approach to Cage. Satie and Cage had very many points in common: both were iconoclasts, both delighted in scandalizing their hearers, both explored the borders of silence, both opened up new ways for the very concept of music and of performance.

In October 1916, Winnaretta Singer, married to Prince Edmond de Polignac, commissioned Satie a composition. In her original plan, it should have been something in the line of “background music” for the reading of excerpts from Plato’s Dialogues. She had envisioned something akin to a melodrama, but the idea did not meet with Satie’s favour. He preferred a sung work, even though the singing would be very different, in kind, from the operatic style. The original destination was maintained, though: even though the selected excerpts from Plato’s Dialogues represent male characters, the work should be sung by an all-female cast. Satie’s compositional work took place between 1917 and 1918, and, once the composition was ready, he labelled it a “symphonic drama in three parts”, probably alluding – in his mocking way – to Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette. The three parts of the composition represent respectively a “portrait of Socrates” (Portrait de Socrate; from Plato’s Symposium), a scene set on “the banks of the Ilissus” (Les bords de l’Ilissus: from Plato’s Phaedrus), and Socrates’ death (Mort de Socrate, from Plato’s Phaedo). Satie’s original composition was scored for voices with accompaniment of orchestra, but he also realised a version for voice(s) and piano. The overall concept of the piece is perfectly summarized in its composer’s words: “The aestetic of this work is dedicated to clarity; simplicity accompanies, directs it. That is all. I wanted nothing more”.

In 1947, about three decades after the composition of Socrate, John Cage transcribed its first movement for two pianos. The stimulus came to Cage from his collaboration with choreographer Merce Cunningham, who elaborated a choreography on Cage’s transcription. Here, therefore, all the “words” of Plato’s Dialogues (which Satie had purposefully wanted to be sung over an antiquated translation, heightening the feeling of alienation) simply disappear. Cage expressed his admiration for Satie as follows: “I love all of Satie’s music and the music of Socrate especially. It seems to me that even though the words he chose are profoundly meaningful and touching, like the delightful and poetic remarks included in his other short pieces, all of which in performances Satie suppressed, the texts of Socrate may be omitted, bring about, as I hope to show in this arrangement, an enjoyment of the music alone, the beauty of which is so constantly clear and extraordinary”.

Further twenty years later, on the fiftieth anniversary of Satie’s original composition (in 1968), Cage and Cunningham completed the transcription and choreography of the remaining two movements, with the purpose in mind of organizing a performance in 1970.

Something, though, intervened and blocked their plans. Cage had employed the original musical material of Satie’s score without the publisher’s permission, and the publisher of Satie’s works formally forbade him to publicly perform the new work. This was a major disappointment. Not only it meant for Cage to renounce his work; this also impacted on the choreographer’s and on his dance company’s efforts. Clearly, every choreography is tailored on the rhythm and phrasing of the musical piece supporting it. One cannot replace Čajkovskij’s Death of the Swan by Ravel’s Boléro and dance the same steps on both! John Cage brilliantly found the solution for this dilemma. He would compose a work with exactly the same metrical structure as Satie’s Socrates, but with… different notes! Even the new notes were to be derived from Satie’s original, through a complex system making use of the I-Ching, the aleatoric philosophy frequently employed by Cage.

The “questions” asked by Cage to the divinatory principle of the I-Ching were the following:

1) Considering the seven modes (scales) built on the piano’s white keys, which one should be used?

2) Which one, among the “twelve possible chromatic transpositions”, will be used?

Then, on a phrase-by-phrase basis, questions about the specific notes were asked. The result was what Cage called a “chromatic modal piece”. In the first movement of the new work, which Cage humorously called Cheap Imitation, every pitch underwent an individual process of transposition, whilst in the second and third movement transpositions were applied onto larger units (half bars).

Echoing Cage’s ironic title, Cunningham also rebaptized his own choreography, calling it Second Hand. The work was actually premiered on January 9th, 1970, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York City.

In spite of its complex genesis, Cage was evidently satisfied with the work’s result. This was his first “proper” composition after an eight-year intermission, and he liked to play it himself, even though he normally refrained from doing so. There exists a recording played by Cage himself, revealing both his brilliant ideas and his pianistic level. Perhaps the most poignant witness of the interest Cage had in this work of his comes from his own words. They acquire an even more intense meaning if one considers Cage’s usual reticence and tendency to veil and hide his feelings under the cover of irony. He wrote: “In the rest of my work, I’m in harmony with myself … But Cheap Imitation clearly takes me away from all that. So if my ideas sink into confusion, I owe that confusion to love. … Obviously, Cheap Imitation lies outside of what may seem necessary in my work in general, and that’s disturbing. I’m the first to be disturbed by it”.

In the eyes of an iconoclast as Cage, to be troubled by an artwork is something akin to a defeat. Yet, it is what most of us associate with art and its fruition. So, this kind of troubling feeling may be a not-too-hidden admission that, perhaps, the “transcendence” preached by Plato and Socrates did mean something for both Satie and Cage.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2022

Indeed, we have not a single line written by Socrates; all we know about him comes from Plato’s Dialogues. Yet, since Plato himself was much more than a passive chronicler or an “objective” observer, we may often wonder how much of Plato’s “Socrates” comes from Socrates himself, and how much is the result of Plato’s afterthoughts on his teacher’s speeches.

Still, this is and will remain an unanswered and unanswerable question. What we do have is the magnificent repertoire of Plato’s Dialogues, which exemplify – as very few other works of art do – the power of the word, of the logos, of the dialectic encounter among human beings mediated by speech, and how speech influences the very forms (or ideas, as Plato would have put it!) of our thought.

The curious aspect of the works recorded here is that they are objectively grounded on and derived from the text of Plato’s Dialogues, but are wordless. The effect is similar to what happens when, for instance, the drama where “words, words, words” is uttered (i.e. Shakespeare’s Hamlet) is turned into a symphonic poem, as in Čajkovskij’s eponymous work. In principle, the idea seems very bizarre and abstruse: take Shakespeare’s “words” from Hamlet and what remains is a rather absurd plot, which, moreover, will not be understood by following the musical score alone. Still, the result can be a masterpiece, if the composer is imaginative and creative enough – as happens, in fact, with Čajkovskij’s symphonic poem.

We cited Čajkovskij’s Hamlet, but we might also have cited Hector Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette, a mammoth symphonic poem which narrates, in over one and a half hour, the story of Shakespeare’s unfortunate lovers. And it is precisely from Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette that Erik Satie took inspiration for his Socrate. “To take inspiration”, however, should be understood in the very idiosyncratic way required every time we deal with Satie. Berlioz’s work is majestic, long, rich in themes and timbres, sounds and ideas, to the point that it can be slightly overwhelming. It narrates the quintessential love story in an involving and touching fashion.

By way of contrast, Satie’s Socrates is much shorter, it involves verbality, it is very essential under the viewpoint of timbre, and, from the narrative viewpoint, it is so bare that it can be said to be no story at all. However, there is a “story” behind this Da Vinci Classics album, and we will try to tell it.

This album includes two works by John Cage, which both relate, directly or indirectly, with Satie’s Socrate. And it is from this composition that we will start our approach to Cage. Satie and Cage had very many points in common: both were iconoclasts, both delighted in scandalizing their hearers, both explored the borders of silence, both opened up new ways for the very concept of music and of performance.

In October 1916, Winnaretta Singer, married to Prince Edmond de Polignac, commissioned Satie a composition. In her original plan, it should have been something in the line of “background music” for the reading of excerpts from Plato’s Dialogues. She had envisioned something akin to a melodrama, but the idea did not meet with Satie’s favour. He preferred a sung work, even though the singing would be very different, in kind, from the operatic style. The original destination was maintained, though: even though the selected excerpts from Plato’s Dialogues represent male characters, the work should be sung by an all-female cast. Satie’s compositional work took place between 1917 and 1918, and, once the composition was ready, he labelled it a “symphonic drama in three parts”, probably alluding – in his mocking way – to Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette. The three parts of the composition represent respectively a “portrait of Socrates” (Portrait de Socrate; from Plato’s Symposium), a scene set on “the banks of the Ilissus” (Les bords de l’Ilissus: from Plato’s Phaedrus), and Socrates’ death (Mort de Socrate, from Plato’s Phaedo). Satie’s original composition was scored for voices with accompaniment of orchestra, but he also realised a version for voice(s) and piano. The overall concept of the piece is perfectly summarized in its composer’s words: “The aestetic of this work is dedicated to clarity; simplicity accompanies, directs it. That is all. I wanted nothing more”.

In 1947, about three decades after the composition of Socrate, John Cage transcribed its first movement for two pianos. The stimulus came to Cage from his collaboration with choreographer Merce Cunningham, who elaborated a choreography on Cage’s transcription. Here, therefore, all the “words” of Plato’s Dialogues (which Satie had purposefully wanted to be sung over an antiquated translation, heightening the feeling of alienation) simply disappear. Cage expressed his admiration for Satie as follows: “I love all of Satie’s music and the music of Socrate especially. It seems to me that even though the words he chose are profoundly meaningful and touching, like the delightful and poetic remarks included in his other short pieces, all of which in performances Satie suppressed, the texts of Socrate may be omitted, bring about, as I hope to show in this arrangement, an enjoyment of the music alone, the beauty of which is so constantly clear and extraordinary”.

Further twenty years later, on the fiftieth anniversary of Satie’s original composition (in 1968), Cage and Cunningham completed the transcription and choreography of the remaining two movements, with the purpose in mind of organizing a performance in 1970.

Something, though, intervened and blocked their plans. Cage had employed the original musical material of Satie’s score without the publisher’s permission, and the publisher of Satie’s works formally forbade him to publicly perform the new work. This was a major disappointment. Not only it meant for Cage to renounce his work; this also impacted on the choreographer’s and on his dance company’s efforts. Clearly, every choreography is tailored on the rhythm and phrasing of the musical piece supporting it. One cannot replace Čajkovskij’s Death of the Swan by Ravel’s Boléro and dance the same steps on both! John Cage brilliantly found the solution for this dilemma. He would compose a work with exactly the same metrical structure as Satie’s Socrates, but with… different notes! Even the new notes were to be derived from Satie’s original, through a complex system making use of the I-Ching, the aleatoric philosophy frequently employed by Cage.

The “questions” asked by Cage to the divinatory principle of the I-Ching were the following:

1) Considering the seven modes (scales) built on the piano’s white keys, which one should be used?

2) Which one, among the “twelve possible chromatic transpositions”, will be used?

Then, on a phrase-by-phrase basis, questions about the specific notes were asked. The result was what Cage called a “chromatic modal piece”. In the first movement of the new work, which Cage humorously called Cheap Imitation, every pitch underwent an individual process of transposition, whilst in the second and third movement transpositions were applied onto larger units (half bars).

Echoing Cage’s ironic title, Cunningham also rebaptized his own choreography, calling it Second Hand. The work was actually premiered on January 9th, 1970, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York City.

In spite of its complex genesis, Cage was evidently satisfied with the work’s result. This was his first “proper” composition after an eight-year intermission, and he liked to play it himself, even though he normally refrained from doing so. There exists a recording played by Cage himself, revealing both his brilliant ideas and his pianistic level. Perhaps the most poignant witness of the interest Cage had in this work of his comes from his own words. They acquire an even more intense meaning if one considers Cage’s usual reticence and tendency to veil and hide his feelings under the cover of irony. He wrote: “In the rest of my work, I’m in harmony with myself … But Cheap Imitation clearly takes me away from all that. So if my ideas sink into confusion, I owe that confusion to love. … Obviously, Cheap Imitation lies outside of what may seem necessary in my work in general, and that’s disturbing. I’m the first to be disturbed by it”.

In the eyes of an iconoclast as Cage, to be troubled by an artwork is something akin to a defeat. Yet, it is what most of us associate with art and its fruition. So, this kind of troubling feeling may be a not-too-hidden admission that, perhaps, the “transcendence” preached by Plato and Socrates did mean something for both Satie and Cage.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2022

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

Facebook

Twitter

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads